Astrong predictor of the development of antisocial behavior is antisocial personality disorder in one or both parents; this seems to be due to both environmental and genetic factors (

1). Numerous studies of humans (clinical groups, aged 6 years to adult) (

2) and nonhuman primates (

3) have demonstrated associations between hostile-aggressive behavior and low CSF levels of the serotonin metabolite 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA). One way to help clarify the direction of causal influences in the relation between serotonin and aggression is to determine whether low levels of CSF 5-HIAA existing before the development of antisocial behavior might be associated with genetic risk for antisocial development. To our knowledge, this has never previously been studied in humans.

Heritability and stability of interindividual differences in CSF 5-HIAA have been demonstrated in nonhuman primates (

3), but studies of humans (reviewed recently [4]) have been inconclusive. We previously demonstrated (

4) that 5-HIAA could be reliably assayed from samples of “leftover” CSF obtained from febrile newborns (N=119) for whom meningitis was ruled out and that interindividual differences in 5-HIAA were stable over the first year of life (correlation between time 1 and time 2: r=0.64, N=31, p<0.01). For this study, we hypothesized that infants with family histories positive for antisocial personality disorder would have lower CSF 5-HIAA levels than those without such family histories. Since there are no known predisposing demographic factors for fever in babies, studies of cohorts of such infants provide an opportunity to measure CSF 5-HIAA within an epidemiologic sampling frame.

METHOD

Leftover portions of the second aliquot of CSF drawn from 646 febrile infants (age, birth to 3 months) in the emergency department at St. Louis Children's Hospital during the calendar year 1995 were assayed for 5-HIAA by using high-performance liquid chromatography (

4). For four infants, leftover samples were also available from the first and fourth 0.75-ml aliquots drawn at lumbar puncture, and the samples showed significant gradient effects: the first aliquots had lower mean 5-HIAA levels than the fourth aliquots (t=–4.50, df=3, p=0.02). The medical records of all 646 infants were reviewed, and 350 infants were excluded from the study on the basis of neurologic abnormalities (

4).

For the 296 remaining children, attempts were made to interview at least one parent during 1996. We reached 199 (67.2%) of the families, of whom 195 agreed to participate. The characteristics of these families were representative of the population of the St. Louis metropolitan area. The group of children whose families could not be reached differed from the group studied in terms of race (35% Caucasian versus 53% in the group that was reached) but not in terms of mean 5-HIAA level, gender, age at the time of lumbar puncture, or birth weight. After complete description of the study to the subjects' parents, written informed consent was obtained. We conducted the Family History Assessment Module (

5) and the Denver Developmental Screening Test II (

6) on the basis of the parents' reports. The validity of the Family History Assessment Module in screening for DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders was established in a study comparing family histories with direct diagnostic interviews of 2,654 individuals (

5). Two children were excluded from the study because of developmental delays.

RESULTS

The prevalence rates for lifetime psychiatric disorders among the 2,338 adult first- and second-degree relatives of the 193 infants, as ascertained by the Family History Assessment Module, were as follows: antisocial personality disorder—2% alcoholism—4% drug abuse—2% major depression—5% lifetime history of suicide attempt—1%.

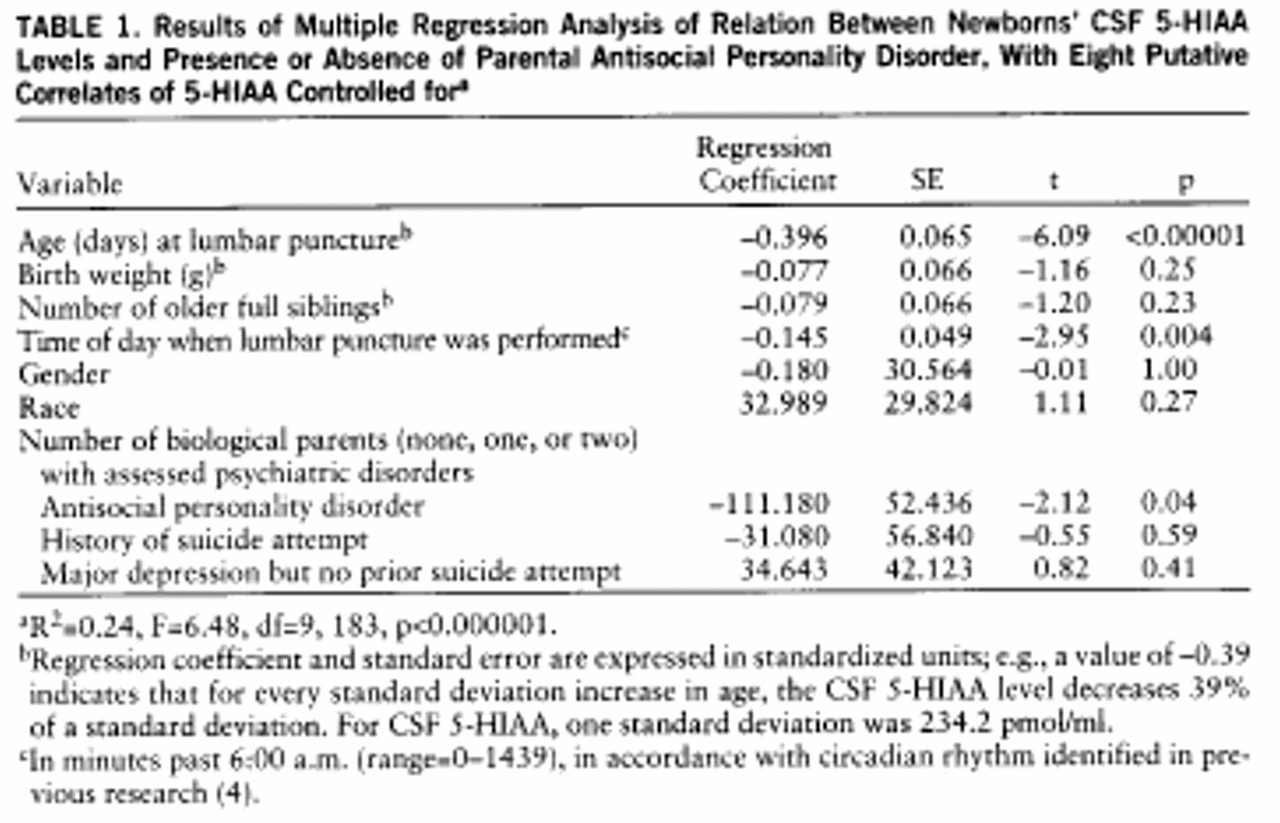

Linear regression analysis revealed that age, time of lumbar puncture, and having a parent with antisocial personality disorder independently predicted 5-HIAA level, as shown in

table 1. Infants who had parents with antisocial personality disorder (N=16) had lower age-adjusted 5-HIAA levels (mean=735 pmol/ml, SD=167) than did infants with negative family histories of antisocial personality disorder (mean=827 pmol/ml, SD=210) (t=1.68, df=173, p=0.05, one-tailed). The mean level of the infants for whom antisocial personality disorder occurred exclusively among second-degree relatives (N=20) was intermediate between those of the other two groups (mean=805 pmol/ml, SD=250) (single-factor analysis of variance for all three groups: F=1.39, df=2,190, p=0.25). There was a low but statistically significant correlation (r=0.12, N=193, p<0.05) between CSF 5-HIAA level and degree of relatedness to the closest family member positive for antisocial personality disorder (i.e., distance, in number of meiotic divisions, to the closest relative with antisocial personality disorder). Seven infants in the lowest 10% of the distribution of age-adjusted 5-HIAA levels had first- or second-degree relatives with antisocial personality disorder, compared to two such relatives for the infants in the upper 10% of the distribution (Fisher's exact p=0.06). There was no significant difference in 5-HIAA level between the infants whose relatives with antisocial personality disorder were violent and the infants whose relatives with antisocial personality were not violent.

Separate linear regression analyses were subsequently performed for each disorder assessed on the Family History Assessment Module; there was no statistically significant association of 5-HIAA with family history of major depression, suicide, mania, schizophrenia, drug abuse, or alcoholism.

DISCUSSION

These data demonstrate a modest but statistically significant inverse association between family history of antisocial personality disorder and CSF 5-HIAA level in newborns. Although the data suggest that family history of antisocial personality disorder accounts for less than 5% of the variance in 5-HIAA levels in newborns, there are potential sources of error, including ascertainment of antisocial personality disorder by family history, reliability of the CSF sampling method, unassessed factors for which infants seen in emergency rooms for fever might not be representative of the population, and the possibility of dominant rather than additive genetic influences on 5-HIAA level. Any of these factors could have led to underestimation of the magnitude of genetic influences on the relation between 5-HIAA and antisocial personality disorder. One premise of the study is that heritable interindividual differences in CSF 5-HIAA are relatively preserved from birth to adulthood. It is possible that genetic factors are involved in individual-specific changes in 5-HIAA over the life course.

If one assumes relative stability of interindividual differences in 5-HIAA over the life course and if it is true that family history of antisocial personality disorder accounts for less than 5% of the variance in newborns' CSF 5-HIAA levels, these findings raise questions about causal relationships that have been inferred from associations between 5-HIAA and antisocial behavior in one-time samplings of violent individuals. Alternative explanations for the association would include 1) the possibility that environmental factors influence both 5-HIAA and social behavior in humans and 2) the likelihood that some of the genetic liability for antisocial behavior is mediated by factors other than the serotonin system.