Research indicates that individual differences in human personality can be summarized by three to five independent dimensions (

1). Status on each of these dimensions is stable over the adult lifespan (

2) and typically shows heritabilities on the order of 50% (

3). However, the physiological substrates underlying these personality dimensions have not yet been elucidated. Spurred by advances in psychopharmacology, several theorists have proposed that brain biogenic amine mechanisms may contribute to the phenotypic expression of some of these dimensions, particularly those which involve affective and motivational processes (

4–

6).

Consistent with these speculations, clinical studies of psychiatric patients suggest that low brain serotonin activity may be related to psychiatric disorders involving hostile affect and aggressive behavior. For instance, people with a history of impulsively violent behavior (e.g., arsonists, violent criminals, people who die by violent methods of suicide) have low CSF serotonin metabolite levels (

7). In addition, patients with violent histories (e.g., with antisocial personality disorder) show signs of compromised brain serotonin function, as assessed by neuroendocrine probes (

8). Finally, pharmacological interventions that augment serotonergic efficacy can reduce hostile sentiment and violent outbursts in aggressive psychiatric patients (

9).

In contrast, the impact of serotonergic interventions on hostile personality characteristics in normal individuals has received less investigation. Impairment of brain serotonin function by means of precursor depletion can induce depressive affect (

10,

11) and may potentiate hostile behavior (

12,

13) in normal control subjects. At the time this study was conducted, no one had investigated whether augmentation of brain serotonin would affect hostility variables in normal volunteers. If enhancement of brain serotonergic function reduces hostility, might such effects remain focal only to hostility variables, or might they be attributable to broader changes in affective personality variables? For example, might administration of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) reduce negative affect (including sadness, anxiety, and other negative emotions in addition to hostility) or increase positive affect? To address these questions, we used a pharmacologically selective intervention to alter brain serotonin function in normal subjects and observed subsequent changes in standard affective personality variables over 4 weeks.

A second but related body of research suggests that brain serotonin function also plays a role in the social behavior of nonhuman primates. For instance, rhesus monkeys with low CSF serotonin metabolite levels show more spontaneous aggression toward conspecifics, receive more wounds, and die at a younger age (

14,

15), while those with high CSF serotonin metabolite levels show greater proximity to and grooming of peers and have a greater number of neighbors living nearby (

16). Serotonergic interventions change primate social behavior in ways that are consistent with these naturally occurring correlations. For example, chronic administration of agents that eventually deplete serotonin (i.e., fenfluramine) increases aggression and locomotor activity in male vervet monkeys (

17), while serotonergic augmentation through either dietary increases in serotonin precursors (i.e., tryptophan) or a pharmacological blockade of serotonin reuptake (i.e., fluoxetine) reduces aggression, vigilance, and locomotion (

18) and increases proximity to and grooming of peers (

19). To address the hypothesis that augmentation of central serotonergic function would increase affiliative behavior in humans, we observed the effects of our serotonergic intervention on the social behavior of normal humans in the context of a cooperative dyadic puzzle task.

METHOD

Subjects and Treatment

We examined the effects of a serotonergic reuptake blockade on personality and social behavior in a double-blind protocol by randomly assigning 51 medically and psychiatrically healthy volunteers to treatment with either an SSRI, paroxetine, 20 mg/day p.o. (N=25), or placebo (N=26). Paroxetine was selected because of its relatively potent and specific inhibition of the serotonin reuptake mechanism in comparison with other SSRIs (

20), although any SSRI may have secondary effects on other monoamine systems (

21). Volunteers were recruited by advertisements in a local weekly newspaper. They gave written informed consent and were screened to exclude subjects with a history of or with first-degree relatives with a history of axis I disorders or dysthymia, as determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Non-Patient Edition (

22). Volunteers were also screened to exclude subjects with a history of psychotropic medication or substance abuse and subjects taking concurrent medications (including birth control pills in the case of women). Volunteers were informed of the possibility of physical side effects but not of the hypotheses. After complete description of the study, written informed consent was obtained from volunteers. One man and one woman in the paroxetine group did not complete the experiment because of side effects, while a second woman in the control group did not complete the experiment because of scheduling conflicts, leaving a total of 23 volunteers in the SSRI group (nine women and 14 men) and 25 in the placebo group (11 women and 14 men). The mean ages of SSRI-treated (mean=26.7 years, SD=2.9) and placebo-treated (mean=27.9, SD=4.2) volunteers did not differ.

Psychometric Measures

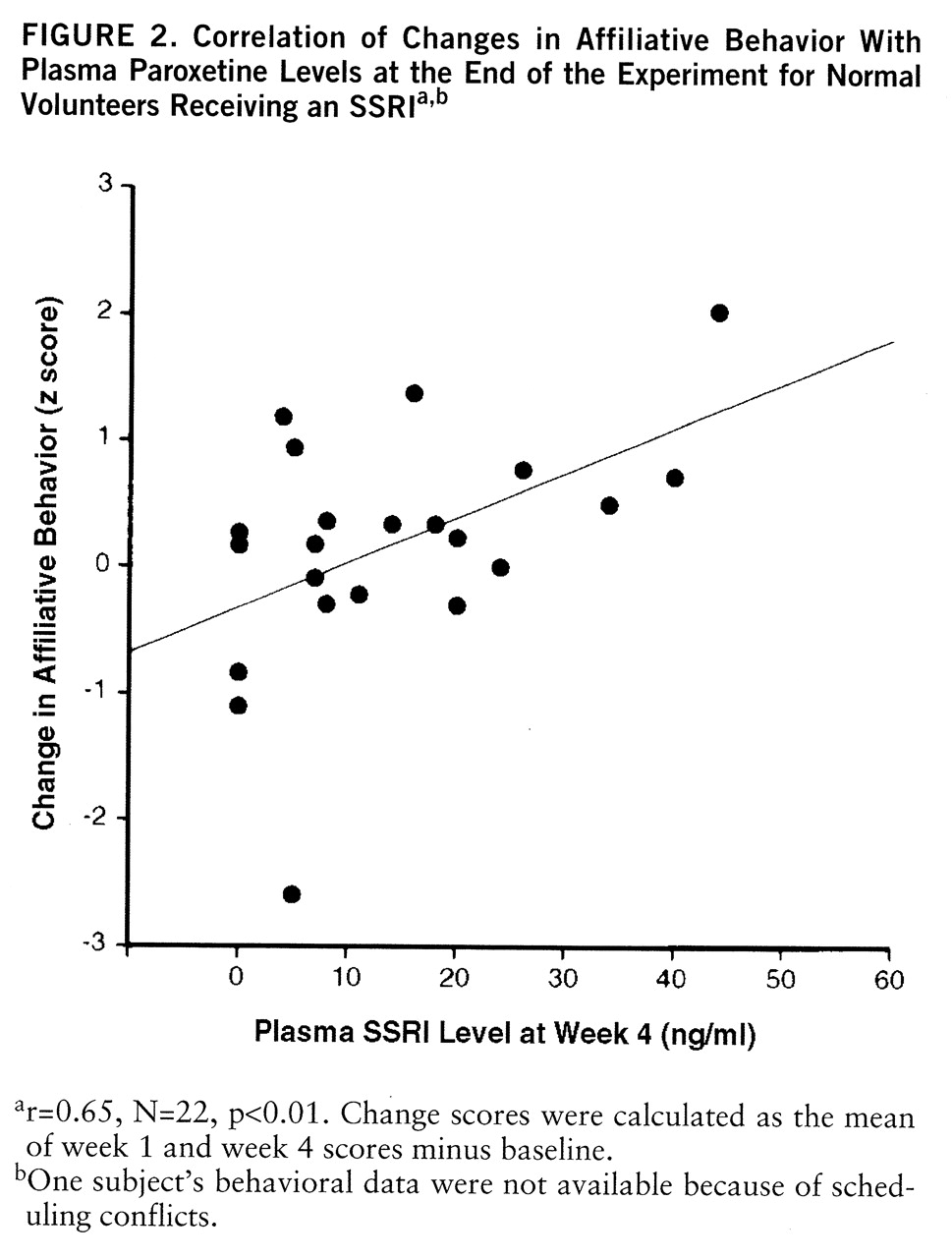

Standard psychometric and behavioral measures were administered at three times: at baseline, after 1 week of treatment, and after 4 weeks of treatment (i.e., at the end of the study). At each assessment, hostility was assessed with the assaultiveness and irritability subscales of the Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (

23), as suggested by Siever and Trestman (

24). To determine whether changes in hostility could be accounted for by more general changes in affective dimensions of personality, we also administered the Positive and Negative Affect Scales. Prior research has shown that different negative affects (e.g., hostility, fear) tend to be correlated in incidence, as do different positive affects (e.g., happiness, excitement). However, negative and positive affects tend to be uncorrelated with each other rather than inversely correlated, and so they are conceptualized as independent trait dimensions (

25). To enhance the sensitivity of all psychometric measures to change over time, participants were asked to respond to the questionnaires in terms of their experience during the previous week.

Behavioral Measures

Objective behaviors were elicited at each assessment in the context of a standardized dyadic puzzle task. The task was designed to elicit face-valid social behaviors that could be reliably coded within the context of a cooperative interaction and subsequently compared across repeated measurement occasions. During the task, each subject collaborated with a partner in planning and implementing solutions for different spatial puzzles (also known as tangrams). Subject pairs were given 10 minutes to combine a set of seven puzzle pieces into configurations that matched as many target shapes as possible, with the stipulation that only one partner could touch the puzzle pieces at a time. Pairs always consisted of one SSRI- and one placebo-treated subject, and novel partners were assigned at each assessment. Neither the subjects nor the experimenter knew the experimental condition of pair members. One of the subjects in the SSRI group did not participate in the baseline puzzle task because of scheduling conflicts.

Puzzle-solving sessions were videotaped without volunteers' knowledge by a hidden camera placed behind a one-way mirror, so as to preserve the authenticity of the volunteers' nonverbal behavior. At the end of the experiment, an interviewer explained the rationale for the hidden camera and offered volunteers an opportunity to have their behavioral records removed from the analyses and deleted. None chose this option; all released their behavioral records for analysis. Coders who were blind to the volunteers' condition subsequently scored the videotapes for various objective social behaviors indicative of cooperation. Specifically, making suggestions while a partner handled the puzzle pieces was considered cooperative, but issuing commands while the partner handled the puzzle pieces was not. In addition, grasping the pieces with the intent of arriving at a unilateral solution was not considered cooperative. Coders attained significant agreement (intraclass r=0.73, p<0.001) on an aggregate measure composed of these behaviors (i.e., behavioral aggregate=(number of suggestions–number of commands)–number of unilateral grasps), which served as the index of affiliative behavior in subsequent analyses.

Plasma Measures

To determine whether individual differences in SSRI bioavailability might exist and potentially influence results, we assayed paroxetine levels in peripheral blood after 4 weeks of treatment. Assays were performed on samples of venous blood drawn at baseline and week 4. The baseline sample was drawn following an overnight fast, and the week 4 sample was also drawn following an overnight fast, 10 hours after the final dose of paroxetine. Plasma paroxetine was quantitated from these samples by using liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection following precolumn derivatization with dansyl chloride (

26). Intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were all less than 10%.

Physical Symptoms

Participants rated the severity of 16 physical side effects (e.g., nausea, insomnia, trembling) on 7-point Likert scales in a semistructured interview format. Differences between groups in physical symptoms were analyzed by separate variance t tests with a Bonferroni correction (p for 32 comparisons=0.0016).

Statistical Analysis

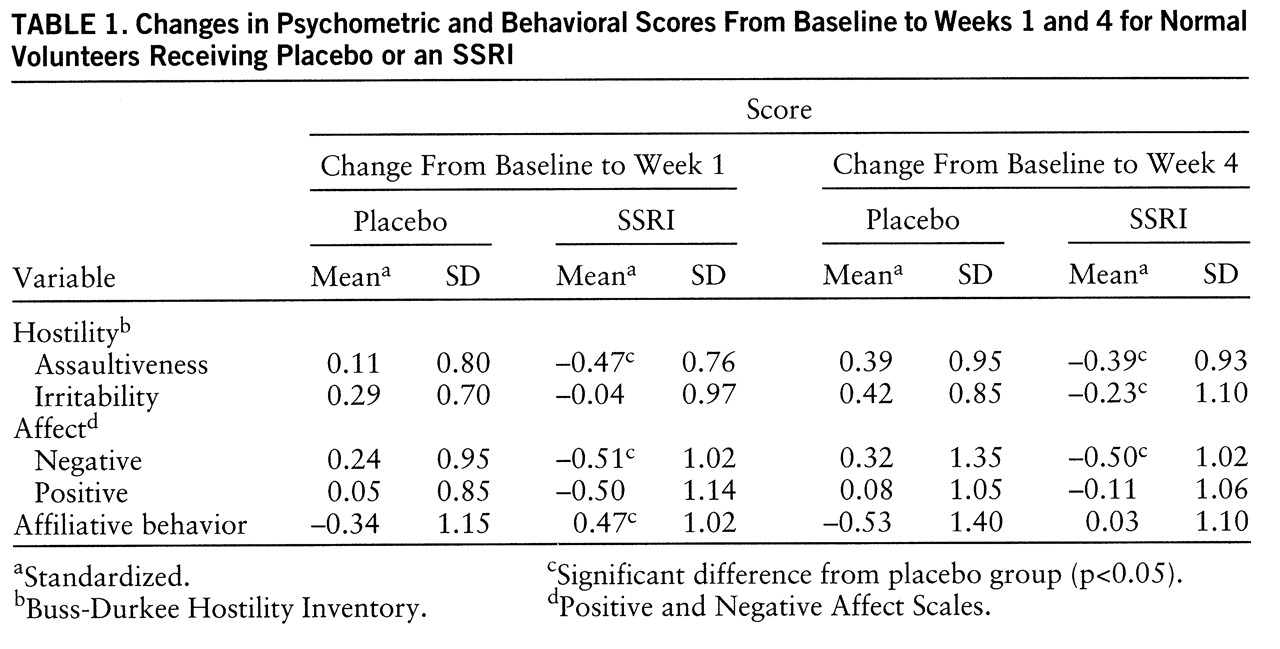

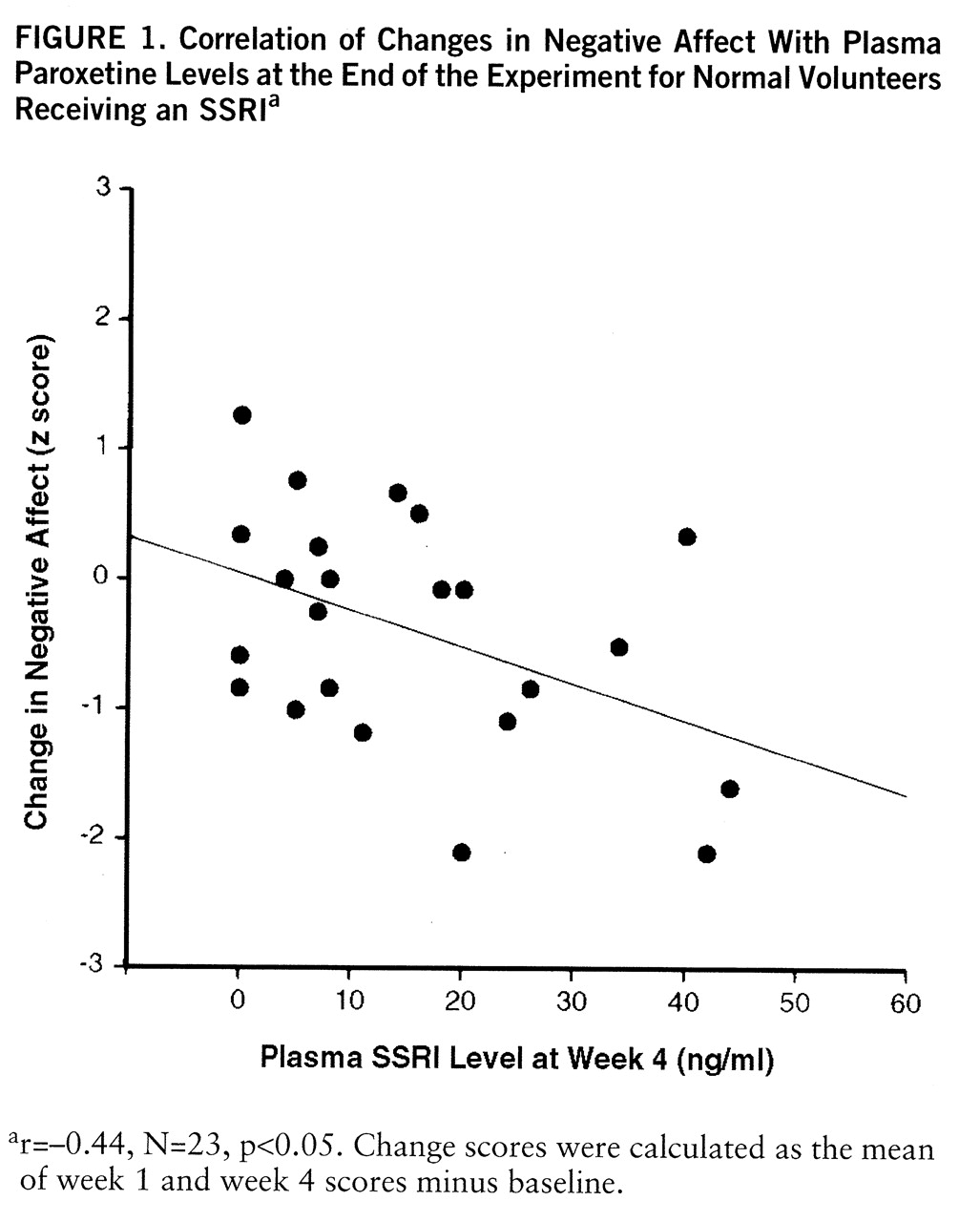

Exploratory data analysis revealed that plasma paroxetine levels varied dramatically among treated individuals (range=0–44 ng/ml, with an approximate fivefold variation across the interquartile range: 5–24 ng/ml) and that changes in both psychometric and behavioral indices were strongly correlated with changes in plasma paroxetine level. Thus, psychometric and behavioral data were analyzed in two ways: 1) with a traditional group-based approach (i.e., a 2-by-3 [treatment-by-time within] repeated measures analysis of variance), and 2) with a similar statistical model that substituted continuous changes in plasma paroxetine levels for the dichotomous grouping variable as a predictor of psychometric and behavioral changes (

27). Five individuals in the SSRI-treated group showed plasma paroxetine levels below 5 ng/ml, suggesting either failure to comply with the treatment regimen or negligible bioavailability. Thus, these individuals were excluded a priori from the group-based (but not plasma-based) analyses. All individuals were included in the plasma analysis, and the plasma change value assigned to control subjects was 0, since they did not take the medication.

Differential rates of change in the SSRI-treated and placebo-treated groups were assessed by a series of pairwise contrasts on change scores from one time point to another. Specifically, effects related to early physiological changes were assessed by a planned contrast comparing changes from baseline to week 1 across groups. Effects related to later physiological changes were assessed by a second planned contrast comparing changes from baseline to week 4 across groups. Finally, differential effects of early and later physiological changes were assessed by a third planned contrast comparing changes from week 1 to week 4. All data were standardized by using the pooled mean and standard deviation of scores at baseline. All a priori hypothesis tests were two-tailed and used p<0.05 as the significance criterion.

DISCUSSION

These data indicate that SSRI administration can modulate some aspects of personality in normal human volunteers. Furthermore, these changes show some functional selectivity. First, SSRI administration reduced psychometric assaultiveness relative to placebo; this finding extends the generalizability of clinical observations that SSRIs can reduce hostile sentiment and violent outbursts in aggressive psychiatric patients (

29). Second, SSRI administration reduced negative affect relative to placebo, and this shift could statistically account for reductions in assaultiveness, which suggests that SSRIs may modulate a broader range of affective variables than those strictly related to hostility. Third, SSRI administration did not significantly alter positive affect, which indicates that global effects on arousal (as in the case of sedation) could not account for the observed reductions in negative affect. While changes in positive affect did show a nonsignificant trend toward diminution at week 1, the change was not significant and was unrelated to plasma paroxetine levels at the study's conclusion. Overall, these findings support theories which posit that separable neurochemical substrates modulate the expression of negative and positive affect (

30,

31).

Besides modulating psychometric indices of negative affect, SSRI administration also enhanced behavioral indices of social affiliation in a cooperative task. While collaboratively solving a puzzle, SSRI-treated partners scored higher on an affiliative behavioral composite consisting of increased suggestions, decreased commands, and decreased unilateral solution attempts at week 1 of testing. It is unclear why this group difference did not persist until week 4, but affiliative behavior at week 4 nevertheless remained correlated with plasma paroxetine levels. Drops in affiliative behavior for both groups across time may have diminished potential group differences at week 4. These findings in human volunteers complement primate studies in which chronic SSRI treatment of male vervet monkeys enhanced a constellation of affiliative behaviors, which in turn led to increased status (

19). However, affiliative behavior may raise one's status only in certain social contexts (e.g., in the absence of a preexisting dominance hierarchy, in the presence of peers who reciprocate affiliative behavior [32, 33]). Thus, while this work suggests that chronic SSRI administration can enhance affiliative behavior of normal volunteers in a cooperative task with novel partners, more research is needed on interpersonal effects of SSRI treatment in other types of social scenarios (e.g., competitive).

Analyses across time points suggested that both psychometric and behavioral effects at week 1 did not change appreciably by week 4. This may indicate that early SSRI-induced physiological changes (i.e., increased synaptic availability of serotonin) are at least sufficient to initiate psychometric and behavioral effects in normal subjects. However, it is not clear whether the persistence of these effects until week 4 is also due to early physiological changes or to later ones more commonly associated with antidepressant response (e.g., autoreceptor desensitization). Further, our data do not address whether the observed effects would persist or dwindle over longer periods of SSRI administration.

Besides differences between groups, the magnitude of changes in psychometric assaultiveness, irritability, negative affect, and behavioral affiliation was correlated with plasma levels of SSRI among SSRI-treated volunteers. Indeed, plasma SSRI predicted functional changes more robustly than did group assignment. This association is somewhat surprising, given that plasma SSRI levels do not consistently predict antidepressant response in clinically depressed patients (

34). On the other hand, depressed patients who eventually respond to tricyclic antidepressants do show early changes in negative affect (e.g., at 10 days) that are more strongly associated with subsequent shifts in cerebrospinal serotonin metabolites than with depressive status per se (

35). Thus, our measures may be tapping a continuum of early subsyndromal changes that either presage or bear no relation to later therapeutic responses in psychiatric patients. Others have recently reported that 6 weeks of SSRI (fluoxetine) administration did not alter the affect of normal volunteers (

36), but these investigators sampled a smaller number of subjects (N=6) and did not include individual difference measures of SSRI metabolism. Verification of the utility of these measures in predicting affective change awaits further replication.

Clearly, volunteers were not all equally affected by SSRI administration. An open-ended interview at the study's conclusion revealed that SSRI effects were often manifested in subtle and seemingly idiosyncratic ways. For example, SSRI-treated volunteers' responses to the question “What did you experience during the experiment?” ranged from “I used to think about good and bad, but now I don't; I'm in a good mood” (highest plasma SSRI level) to “The side effects were intense at first but then tapered off” (lowest plasma SSRI level). Individual differences in responsiveness to the manipulation may have arisen from several sources including (but not limited to) peripheral metabolic differences (e.g., enzymatic breakdown in the liver), central neurochemical differences (e.g., efficacy of the reuptake mechanism, postsynaptic receptor sensitivity), preexisting personality differences (e.g., baseline levels of chronic negative affect), or a combination of these factors. Unfortunately, the current design did not allow us to test for predisposing predictors of change, since correlation of change scores with the baseline scores used in their calculation invokes collinearity. Future studies might address these questions through repeated measures of relevant constructs at baseline.

In sum, this is the first empirical demonstration that chronic administration of a selective serotonin reuptake blockade can have significant personality and behavioral effects in normal humans in the absence of baseline depression or other psychopathology. These findings concur with the recent discovery of an association between a genetic polymorphism that regulates the efficacy of serotonin reuptake and negative affective components of the trait neuroticism. No such association has been observed between the polymorphism and other traits, including positive affective components of extraversion (

37). While the primary application of SSRIs lies within the realm of treating psychiatric disorders, the present work indicates that these agents may provide psychological researchers with powerful tools for the “pharmacological dissection” of distinct phenomenological aspects of normal personality (

38). Studies of normal volunteers with other pharmacologically selective agents may help to further delineate the specificity of serotonergic mechanisms in modulating affect and thereby may enable researchers to elucidate other psychobiological substrates of personality.