There is increasing recognition that individuals who sustain a mild traumatic brain injury can also suffer posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Although some reports claim that PTSD does not occur following mild traumatic brain injury (

1,

2), several case reports demonstrate the presence of PTSD following mild traumatic brain injury (

3,

4). Further, empirical studies estimate the frequency of PTSD after mild traumatic brain injury to be between 17% and 33% (

5–

7).

Acute stress disorder was recently included as a new diagnosis in DSM-IV to describe posttraumatic stress in the initial month after a trauma. Acute stress disorder consists of dissociative, reexperiencing, avoidance, and arousal symptoms. The main difference between acute stress disorder and PTSD is the requirement that for the diagnosis of the former, three dissociative symptoms must be present. A primary reason for the introduction of this diagnosis was its alleged capacity to identify traumatized individuals who would subsequently develop PTSD (

8). This proposition was not based on empirical data, however, and there is a need for prospective studies of the relationship between acute stress disorder and PTSD across a range of trauma populations (

9). We have previously noted that acute posttraumatic stress reactions are reported in 27% of patients with mild traumatic brain injury (

10). No studies have reported the frequency of occurrence of acute stress disorder or investigated the relationship between acute stress disorder and PTSD following mild traumatic brain injury. Accordingly, a major aim of the current study was to investigate the extent to which diagnosed acute stress disorder predicted the subsequent development of PTSD after mild traumatic brain injury.

Diagnosing acute stress disorder following mild traumatic brain injury is potentially problematic because of the potential overlap of acute stress disorder symptoms and postconcussive symptoms. For example, the dissociative symptoms of reduced awareness, depersonalization, derealization, and amnesia are commonly reported during posttraumatic amnesia in individuals with mild traumatic brain injury (

11–

13). This potential difficulty in the differential diagnosis of acute stress disorder and postconcussive symptoms points to the need for close investigation of the capacity of acute stress disorder symptoms to predict those individuals who will develop PTSD after a mild traumatic brain injury. To this end, we investigated the extent to which each of the acute stress disorder symptoms predicted PTSD following mild traumatic brain injury.

RESULTS

At the initial assessment, 11 patients (13.9%) met criteria for acute stress disorder. Six months after the trauma, 15 patients (23.8%) met criteria for PTSD. In terms of those diagnosed with acute stress disorder, nine (81.8%) met criteria for PTSD 6 months after the trauma, and two (18.2%) did not meet criteria. Of those not diagnosed with acute stress disorder, six (11.5%) subsequently met criteria for PTSD, and 46 (88.5%) did not meet criteria.

Table 1 presents data on the patients who reported acute stress disorder symptoms, according to their PTSD status 6 months after the trauma. McNemar's chi-square tests (N=63, df=1, with Yates's correction) were conducted on each symptom (

17). The alpha rate was subjected to a Bonferroni adjustment in which the alpha level was set at 0.003 to provide an overall rejection level of 0.05. Patients who developed PTSD were more likely to report acute numbing, depersonalization, recurrent images and thoughts, avoidance, insomnia, irritability, and motor restlessness than were those who did not develop PTSD.

Table 1 also presents the power of each acute stress disorder symptom to predict PTSD 6 months after the trauma. Positive predictive power was defined as the probability of PTSD developing when an acute stress disorder symptom was present. This probability was calculated by dividing the number of patients who reported each acute stress disorder symptom and who later developed PTSD by the total number of patients who reported each acute stress disorder symptom. Negative predictive power was defined as the probability of not developing PTSD when an acute stress disorder symptom was absent. This probability was calculated by dividing the number of patients who did not report each acute stress disorder symptom and who later did not develop PTSD by the total number of patients who did not report the acute stress disorder symptom. Negative predictive power was strong for all acute stress disorder symptoms. Positive predictive power was strongest for motor restlessness, depersonalization, a sense of reliving the trauma, and recurrent images.

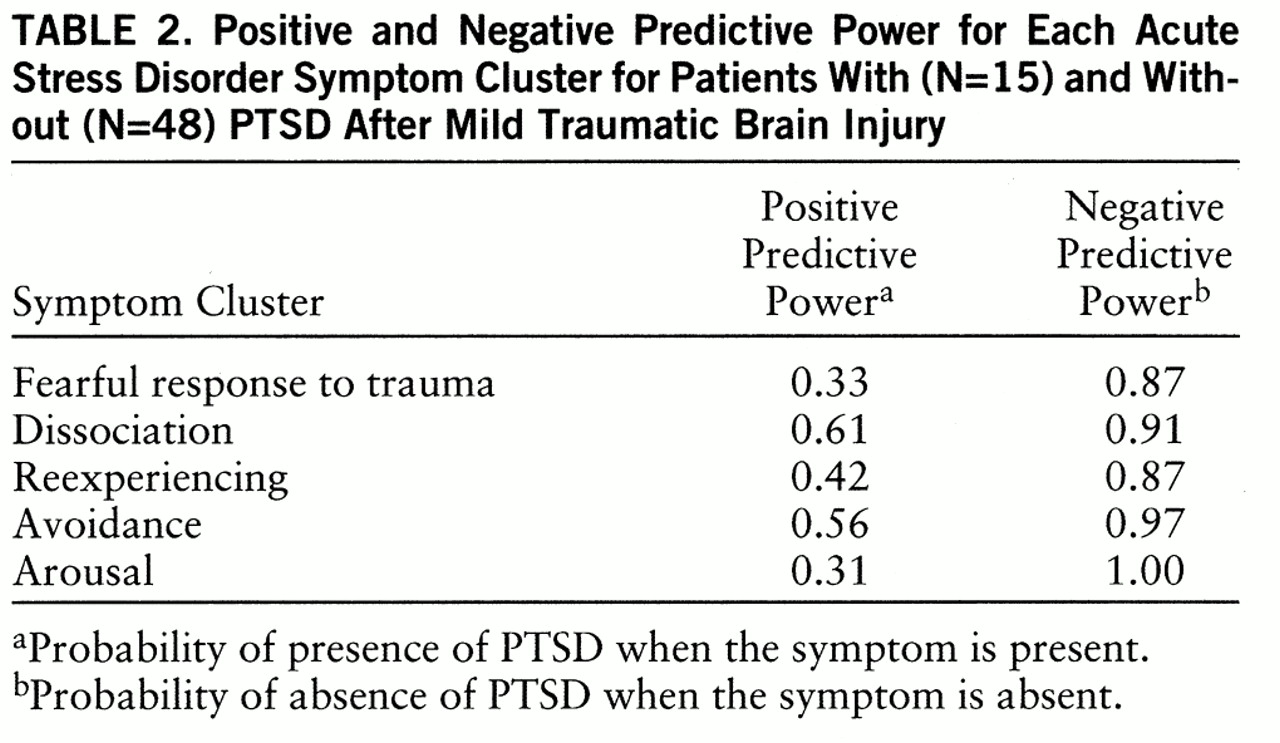

Table 2 presents the positive and negative predictive power of each acute stress disorder diagnostic cluster. Negative predictive power was strong for all clusters. Positive predictive power was strongest for dissociation, moderate for reexperiencing and avoidance, and weak for fearful response to the trauma and arousal. When the criteria were modified so that only two dissociative symptoms were required, negative predictive power for the dissociative cluster remained unchanged (0.91), but there was a slight reduction in positive predictive power (0.55). When two symptoms were required for each of the reexperiencing and avoidance clusters, there was an increase in positive predictive power (0.75 and 0.80, respectively) and little change in negative predictive power (0.88 and 0.94). When two or more symptoms were required to meet criteria for the arousal cluster, positive and negative predictive power changed marginally (0.36 and 0.90, respectively). When three or more symptoms were required, there was a small reduction in negative predictive power (0.95) and a marked increase in positive predictive power (0.62).

DISCUSSION

The finding that 24% of our group met criteria for PTSD adds further support to the growing evidence that individuals who sustain a mild traumatic brain injury can develop PTSD (

5–

7,

10). It is important to note that the frequency of caseness of PTSD in this study, which was indexed through use of a structured clinical interview, is consistent with previously reported estimates of PTSD in nonmild traumatic brain injury populations following a motor vehicle accident (

18). This finding argues strongly against recent claims that PTSD does not occur after mild traumatic brain injury (

1,

2) and suggests that PTSD occurs at comparable rates in populations with mild traumatic brain injury and no brain injury.

The finding that 82% of our final group who met criteria for acute stress disorder displayed PTSD 6 months after the trauma supports the utility of this diagnosis in identifying individuals who may be at risk of longer-term PTSD after a mild traumatic brain injury. Studies of assault victims indicate that the prevalence of PTSD drops at least 50% from 2 weeks after the trauma to 3 months after the trauma (

19). Similarly, in half of a sample who met criteria for PTSD in the initial month after motor vehicle accidents, PTSD had remitted 6 months after the trauma (

20). The much lower remission rate in the current study suggests that the stringent criteria for acute stress disorder identified those severely traumatized patients who were more likely to suffer chronic PTSD. This finding supports recent reports that 78% of non-brain-injured motor vehicle accident survivors with acute stress disorder still suffer PTSD 6 months after the trauma (

21).

Despite the potential confound between acute stress disorder and postconcussive symptoms, the acute stress disorder criteria functioned very well in identifying those patients who suffered persistent PTSD. Although the acute dissociative symptoms may reflect either postconcussive symptoms or dissociation, acute numbing and depersonalization were reported significantly more by those patients who developed PTSD than by those who did not develop PTSD. Further, the potentially overlapping arousal symptoms, such as insomnia, irritability, and restlessness, were reported more often by those patients who developed PTSD. It is possible that those patients who developed PTSD experienced these acute symptoms more often because of the elevated anxiety reaction they suffered following their trauma. Alternatively, it may be argued that their development of PTSD 6 months after the trauma was associated with more severe postconcussive symptoms experienced during the acute phase. Research from non-brain-injured populations indicates that PTSD severity is compounded by stressors that occur following a trauma (

22,

23). The difficulties associated with postconcussive symptoms may have contributed to poor adjustment after the trauma and higher prevalence of PTSD.

The power of specific acute stress disorder symptoms to positively predict chronic PTSD varied from low to moderately strong. Motor restlessness emerged as the strongest single predictor of PTSD. We recognize, however, that the predictive value of this acute symptom requires replication with larger groups. Depersonalization was also a powerful predictor. This finding, together with the moderate to strong predictive power of the other dissociative symptoms, is consistent with previous reports that acute dissociative symptoms predict subsequent PTSD (

8,

24,

25). It is also consistent with findings that numbing is the most characteristic symptom of PTSD in assault victims (

26).

The finding that recurrent images and a sense of reliving the trauma had strong predictive power is consistent with some evidence that initial intrusions are predictive of PTSD (

27). The poor predictive power of other intrusive symptoms accords with evidence that acute intrusions are not highly predictive of long-term PTSD (

28–

30). Similarly, the weaker predictive power of avoidance symptoms supports other prospective studies that have found a weak relationship between initial avoidance and later PTSD (

31,

32). Overall, we found that prediction of PTSD, according to acute stress disorder criteria, following mild traumatic brain injury is improved by making the requirements for reexperiencing, avoidance, and arousal clusters more stringent. The positive predictive power of reexperiencing and avoidance was increased significantly when two symptoms were required in each cluster; such a modification was achieved with little change to the negative predictive power. Further, the arousal cluster predicted PTSD much better when it was stipulated that three arousal symptoms be present. We recognize that these findings are based on patients with mild traumatic brain injury and that these suggested modifications to the criteria need to be evaluated in prospective studies with a range of trauma populations.

Conclusions from this study are restricted by a number of methodological limitations. First, although nonparticipants at the 6-month assessment did not differ in relevant variables from those who participated, it is possible that our group may not be truly representative of populations with mild traumatic brain injury. Second, we acknowledge that our findings cannot be generalized to other trauma populations, which may experience different patterns of acute and longer-term PTSD following mild traumatic brain injury. Finally, we recognize that the current study is limited by its exclusive focus on PTSD. Apart from PTSD, survivors of mild traumatic brain injury experience a range of comorbid conditions, including depression (

5), pain (

33), and postconcussive symptoms (

34). Future research into the longitudinal course of PTSD following mild traumatic brain injury should investigate the interaction between acute stress reactions and the range of comorbid disorders that commonly develop in this population.

These findings represent the first demonstration that acute stress disorder following mild traumatic brain injury is highly predictive of longer-term PTSD. Recent reports indicate that early treatment of acute stress disorder can effectively prevent development of PTSD (

35). Considering the prevalence of PTSD that was observed 6 months after the trauma, the current findings suggest that early intervention in acute stress disorder may prevent development of chronic stress conditions following mild traumatic brain injury. While recognizing the influence of other posttrauma factors in the development of PTSD, the current findings suggest that refining the requisite criteria for the reexperiencing, avoidance, and arousal symptom clusters of acute stress disorder may improve early identification of individuals who are likely to develop chronic PTSD following mild traumatic brain injury.