In contrast to thousands of scientific articles on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in Caucasians, there is limited information about ADHD among African Americans. In an earlier review (

1), we identified only 17 articles about ADHD in African Americans and only a handful having a focus on ethnicity. Since ADHD is a substantial disorder of childhood (

2), the absence of meaningful information relevant to African Americans has clinical and public health implications.

To help fill this lacuna in the literature, we studied ADHD in African American children using an ethnically sensitive design. We hypothesized that African American children with ADHD would have higher levels of psychiatric dysfunction than African American children who did not have ADHD.

METHOD

The study design and methodology closely followed our earlier studies of Caucasian children (

3,

4). In addition, ethnically sensitive accommodations were made for this study based on recommendations from an advisory committee of 14 African American researchers and mental health professionals. This committee reviewed our methodology for cultural appropriateness.

We recruited African American children between the ages of 6 and 17 who did (N=19) or did not (N=24) have DSM-III-R ADHD. The children with ADHD came from pediatric and psychiatric referral sources. The pediatric source was a large health maintenance organization; the psychiatric source was our pediatric psychopharmacology unit. Subjects were excluded from the study if they had been adopted, their nuclear family was not available, or they had paralysis, deafness, blindness, psychosis, autism, or a full-scale IQ less than 80.

The African American children who did not have ADHD were selected from the pediatric medical clinics at the two ascertainment sites and from advertisements. All parents completed consent forms for themselves and their children. Assent forms were obtained from the children. The research project was reviewed and approved by our institutional review board.

Diagnostic assessments used structured interviews based on DSM-III-R. Psychiatric assessments of children used the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—Epidemiologic Version (

5). Diagnoses were based on independent interviews with all of the mothers and direct interviews with the children older than 12.

All assessments were made by six African American raters who were blind to the subject's diagnosis and ascertainment site. These raters were trained and supervised by project investigators (V.J.S., J.B., and D.B.). The ethnic validity model of Tyler et al. (

6) was used to train the raters in cultural sensitivity. We computed kappa coefficients of agreement by having a board-certified child psychiatrist or a licensed clinical child psychologist diagnose children from audiotaped interviews made by the assessment staff. Based on 173 interviews from a larger data set, the median kappa for all diagnoses was 0.86, and the kappa for ADHD was 0.98. In addition, we computed kappa separately for cases in which two African American raters rated an African American child. That kappa was 0.87.

Diagnoses were considered positive if DSM-III-R criteria were unequivocally met. All diagnostic uncertainties were resolved by a committee of three board-certified or licensed clinicians (V.J.S., J.B., D.B.) who were blind to ascertainment group. For children older than 12, data from direct and indirect interviews were combined by considering a diagnostic criterion positive if endorsed in either interview.

Data were analyzed by using t tests and Fisher's exact tests. All tests of significance were two-tailed, and significance was set at the 5% level.

Our findings for this group of African American children with ADHD were compared with those in our earlier study of Caucasian children (

7), which used an identical assessment battery.

RESULTS

The children with and without ADHD did not differ in age (mean=13 years, SD=3, versus mean=12.6 years, SD=3, respectively) (p=0.70, Fisher's exact test), social class (mean=2.1, SD=0.9, versus mean=2.1, SD=0.9) (p=1.00, Fisher's exact test), or number with separated or divorced parents (12 versus 12) (p=0.50, Fisher's exact test).

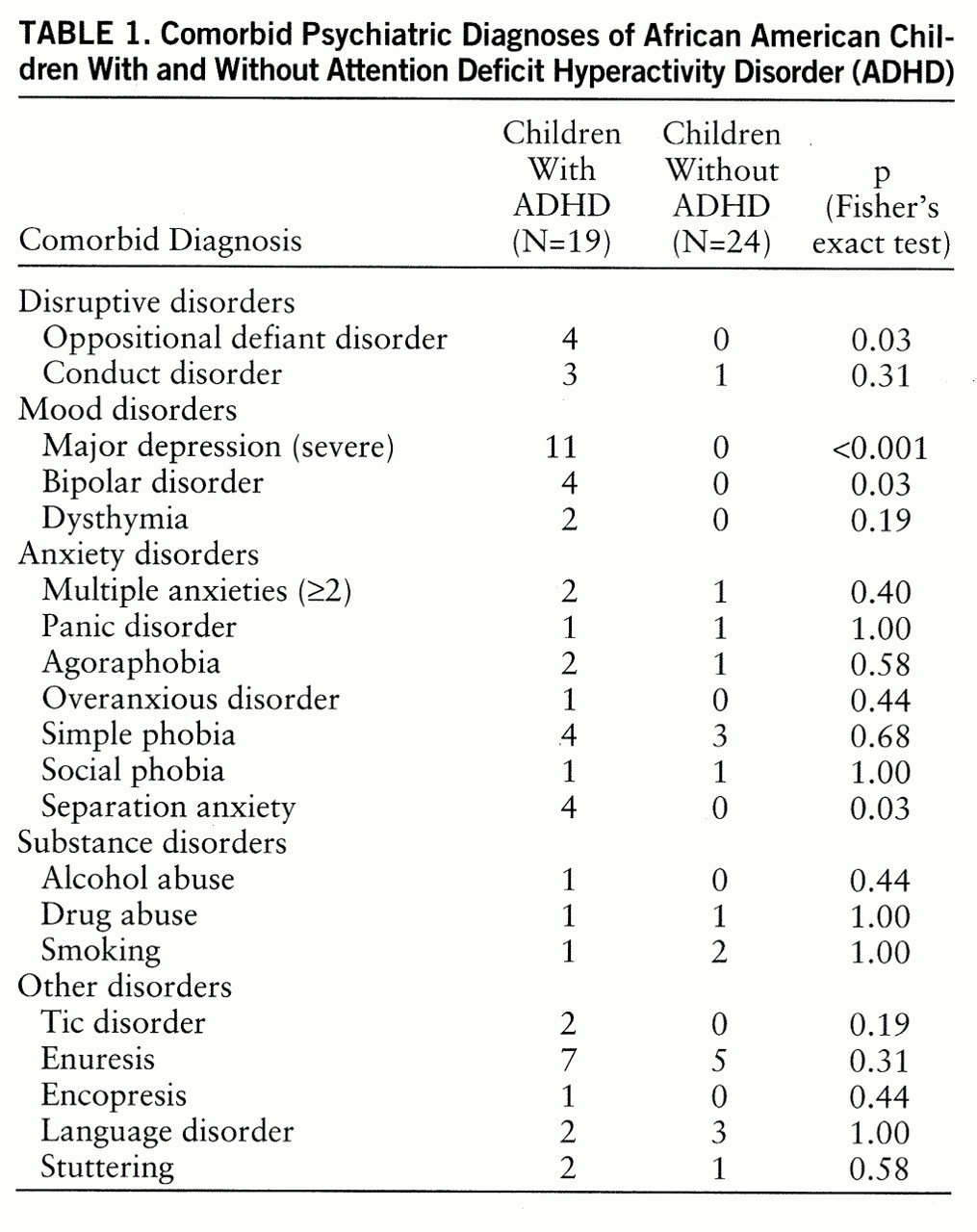

Compared with children who did not have ADHD, the children with ADHD had higher lifetime rates of almost all of the evaluated psychiatric disorders, but there were statistically significant differences only in oppositional defiant disorder, major depression, bipolar disorder, and separation anxiety disorder (

table 1).

The mood disorder findings were consistent with those in our previously reported study of Caucasian children with ADHD (

7), who were assessed with an identical assessment battery. In contrast, the rates of other disruptive behavior and anxiety disorders were comparatively modest in the African American children. The comorbidity of ADHD with disruptive behavior disorders has been associated with poor prognosis, delinquency, and substance abuse in Caucasian children with ADHD (

8,

9). Moreover, comorbidity of ADHD with anxiety disorders has been associated with poor response to stimulant treatment (

10).

DISCUSSION

These African American children with ADHD had the prototypical psychiatric correlates of the disorder: high rates of oppositional defiant, mood, and anxiety disorders. These preliminary findings suggest that the currently accepted definition of ADHD identifies a disorder in African American children with similar—but not identical—psychiatric correlates to those previously identified in Caucasians.

Although a preliminary finding, the modest levels of comorbidity in this study group may indicate that African American children have a potentially more manageable and treatment-responsive form of ADHD.

Our results must be interpreted in the context of methodological limitations. Because the number of subjects was relatively small, we had low statistical power to detect group differences. Moreover, because we made multiple comparisons, some of our results may be type II errors. Because the subjects with ADHD had been referred, our results may not generalize to all children with ADHD. They should, however, generalize to children seen in treatment settings. In addition, because the subjects were primarily from middle-class families, the findings may not generalize to children from other social strata.

Despite these limitations, to our knowledge this work is the first to use ethnically sensitive methods to study ADHD in African American children. Before drawing definitive conclusions, further work is needed to replicate this study with a larger group of African American children. If our findings are replicated, new avenues may be opened for clinicians in the assessment of and treatment planning for African American children with ADHD.