Having made the diagnosis of schizophrenia, the clinician is often asked about the patient’s prognosis. Patients and their families are most interested in the impact of the illness on subsequent quality of life. Will the patient be able to return to work or school? Will he or she relate well to relatives and friends? Lead a normal life? To the patient and the family, symptoms are usually the most prominent features of the disorder during the acute illness. Can symptoms in the acutely disturbed patient tell the clinician anything about subsequent quality of life? Do certain symptoms or groups of symptoms have better prognostic value than others?

Previous studies have examined the prognostic values of premorbid, sociodemographic, and psychopathological variables on outcome in patients with schizophrenia. Poor outcome in schizophrenia has been associated with the presence of the negative syndrome, poor premorbid adjustment, male gender, younger age at onset, insidious onset, longer interval from the onset to treatment, and the absence of any clear precipitating events

(1-

11The symptoms of schizophrenia have commonly been divided into the positive and negative categories. Hughlings Jackson

(12) was the first to use the terms “positive and negative symptoms” in the description of insanity

(13,

14). More recently, Bilder et al.

(15) proposed that there might be a third cluster of symptoms (“disorganization of thought”), independent of the positive/negative construct. Numerous studies that followed have shown that the symptoms of schizophrenia cluster into three dimensions

(16-

26), namely, the negative, psychotic, and disorganized dimensions. Although negative symptoms have been associated with poor outcome, the relationship between the psychotic and disorganized dimensions and subsequent outcome has been less clear. Previous studies have grouped these two dimensions under the category of “positive” symptoms.

In this study, we were interested in knowing if these three symptom dimensions, measured during the acutely disturbed state at the first psychiatric hospitalization, could predict subsequent quality of life. If so, what threshold of severity of symptoms will predict poor quality of life, and at what likelihood?

RESULTS

Symptoms at Intake and at 2-Year Follow-Up

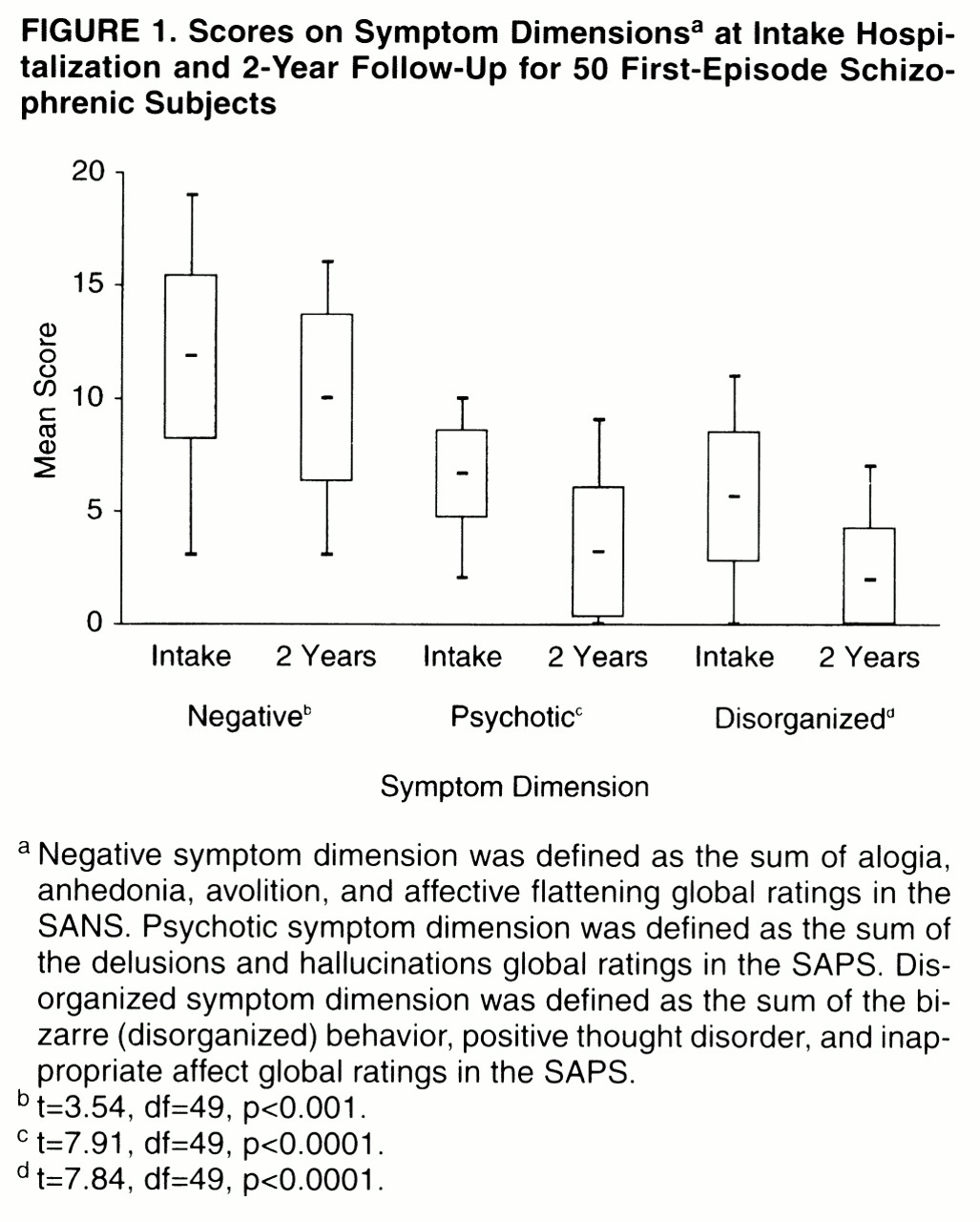

The levels of symptoms at intake and at 2-year follow-up are shown in

Figure 1. Negative symptoms were prominently present at the first hospitalization in this group of acutely ill patients. At 2-year follow-up, the symptoms in all three dimensions improved significantly from intake. Both the psychotic and disorganized dimensions improved considerably more than the negative dimension.

Quality of Life at 2-Year Follow-Up

At follow-up, 60% of the patients were unemployed because of the illness. Another 12% experienced moderate to severe impairment in their capacity to work; 64% were financially supported by social service agencies; and 44% experienced at least moderate impairment in their ability to perform household duties. The level of interpersonal relationship with family members was between good and fair (mean=2.79, SD=0.75, on a 5-point scale; lower scores indicate better relations); on the other hand, 58% of the group had poor or very poor relations with friends, and 48% had “very little enjoyment” from participation in recreational activities or hobbies. Another 4% had no involvement in recreational activities. At 2-year follow-up, 60% of the group had marked or severe impairment, whereas only 12% had mild or no impairment in overall social adjustment. The mean GAS score was 44.7 (SD=11.3). Thus, in this cohort of first-episode subjects, the majority were substantially impaired. Quality of life at 2-year follow-up was generally poor; 50% of the subjects met the criteria for poor outcome as defined earlier in this article.

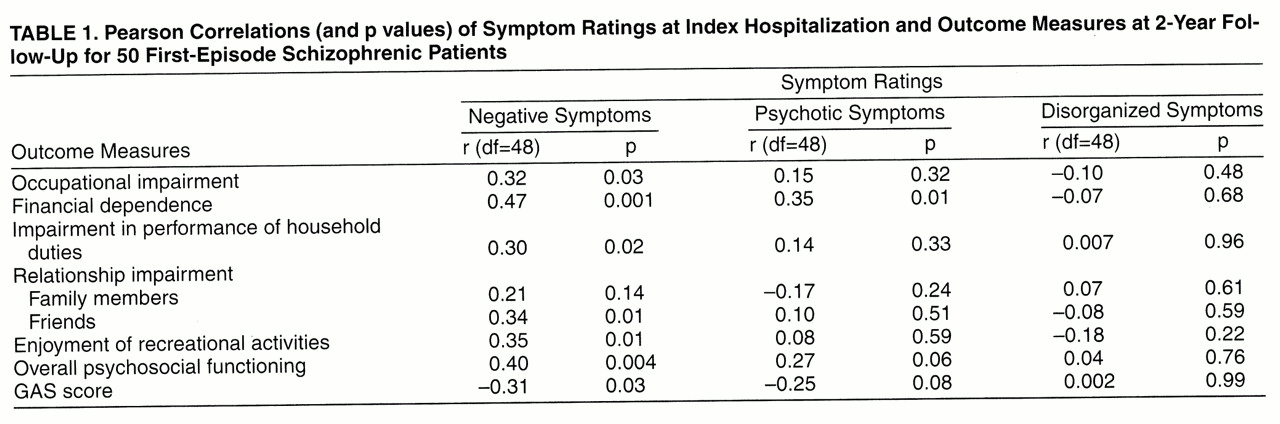

Relationship Between Symptom Dimensions at Intake and Quality of Life at 2-Year Follow-Up

We first analyzed the relationships between the three symptom dimensions and quality of life measures at 2-year follow-up by using Pearson correlation coefficients (

table 1). The level of negative symptoms was moderately and significantly correlated with later occupational impairment, financial dependence on others, impairment in performance of household duties, impaired relationships with friends, impaired ability to enjoy recreational activities, and global assessments of functioning (r values=0.31 to 0.47, df=48, p values <0.03 to 0.0006). Severe negative symptoms at intake were associated with poor quality of life at 2-year follow-up.

Multivariate Analyses

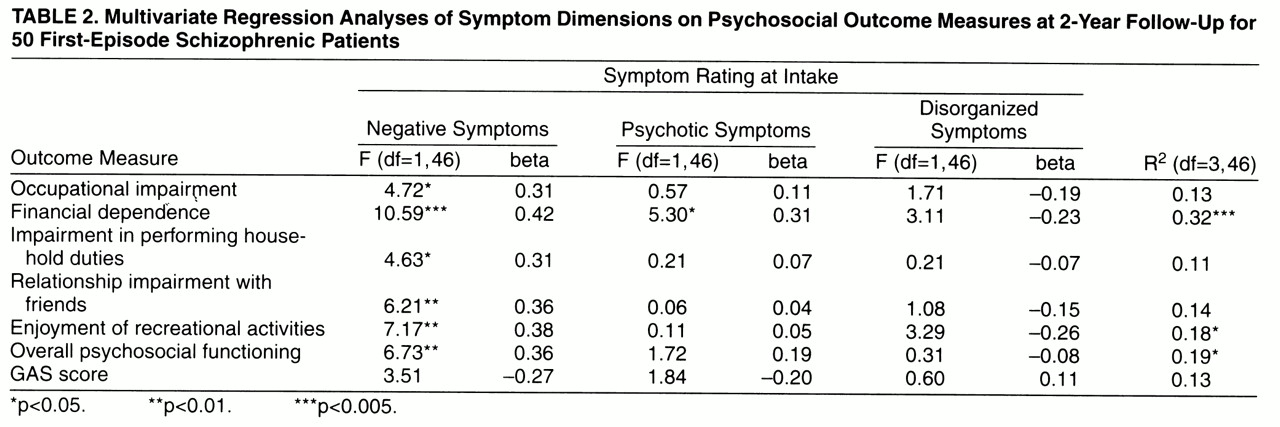

We further analyzed the relation between intake symptom dimensions and quality of life measures at follow-up by using multivariate regression, with each quality of life measure as the dependent variable and the three symptoms dimensions as independent variables. We removed the outcome measure “relationship impairment with family members” from these analyses since there were no significant correlations with intake symptoms. The variance, F values, and standardized regression beta coefficients are summarized in

table 2.

In general, the magnitudes of correlation between psychotic symptoms or disorganized symptoms and 2-year quality of life measures were lower and not statistically significant. The only exception was between psychotic symptoms and subsequent financial dependence on others (r=0.36, df=48, p<0.01).

The scales that measure quality of life and the negative symptom dimension may overlap. Specifically, the anhedonia-asociality and the avolition-apathy global ratings on the SANS also assess occupational functioning, interpersonal relationships, and recreational interests. Instead of using all four SANS global ratings, we did further correlation analyses with only the alogia and affective flattening global ratings as measures of the negative symptom dimension. Although the magnitudes of correlation for only these two global scores (median r=0.26) were lower than those for all four SANS global scores (median r=0.33), higher negative symptoms were still associated with poor quality of life. Thus, in the subsequent analyses, we used all four SANS global ratings as the measure of the negative symptom dimension.

Although the variance in quality of life explained by intake symptoms was moderate at best (11% to 32%), the regression analyses again revealed the same distinct pattern. The beta weights for the negative symptom dimension were consistently higher than the weights given to the other two dimensions in the regression models. The negative symptom dimension was also most consistently the only significant independent variable in these analyses, with two exceptions.

Effects of Prehospitalization Quality of Life Measures and Premorbid Adjustment

Negative symptoms have been associated with poor premorbid functioning. The ability of the negative symptom dimension to predict poor quality of life may have been related to unfavorable premorbid functioning. Therefore, we examined this potential confounding factor by using partial correlation. We examined each 2-year outcome quality of life measure individually, partialing the effects of the corresponding prehospitalization quality of life measure and premorbid adjustment score.

The correlations between premorbid functioning and intake negative symptoms were low (r values=0.01 to 0.18, df=48). After we had partialed out the effects of premorbid functioning, the correlations between the negative symptom dimension at intake and later quality of life remained essentially unchanged from those in

table 1. Thus, independent of premorbid functioning, severe negative symptoms at intake were associated with poorer quality of life at 2-year follow-up.

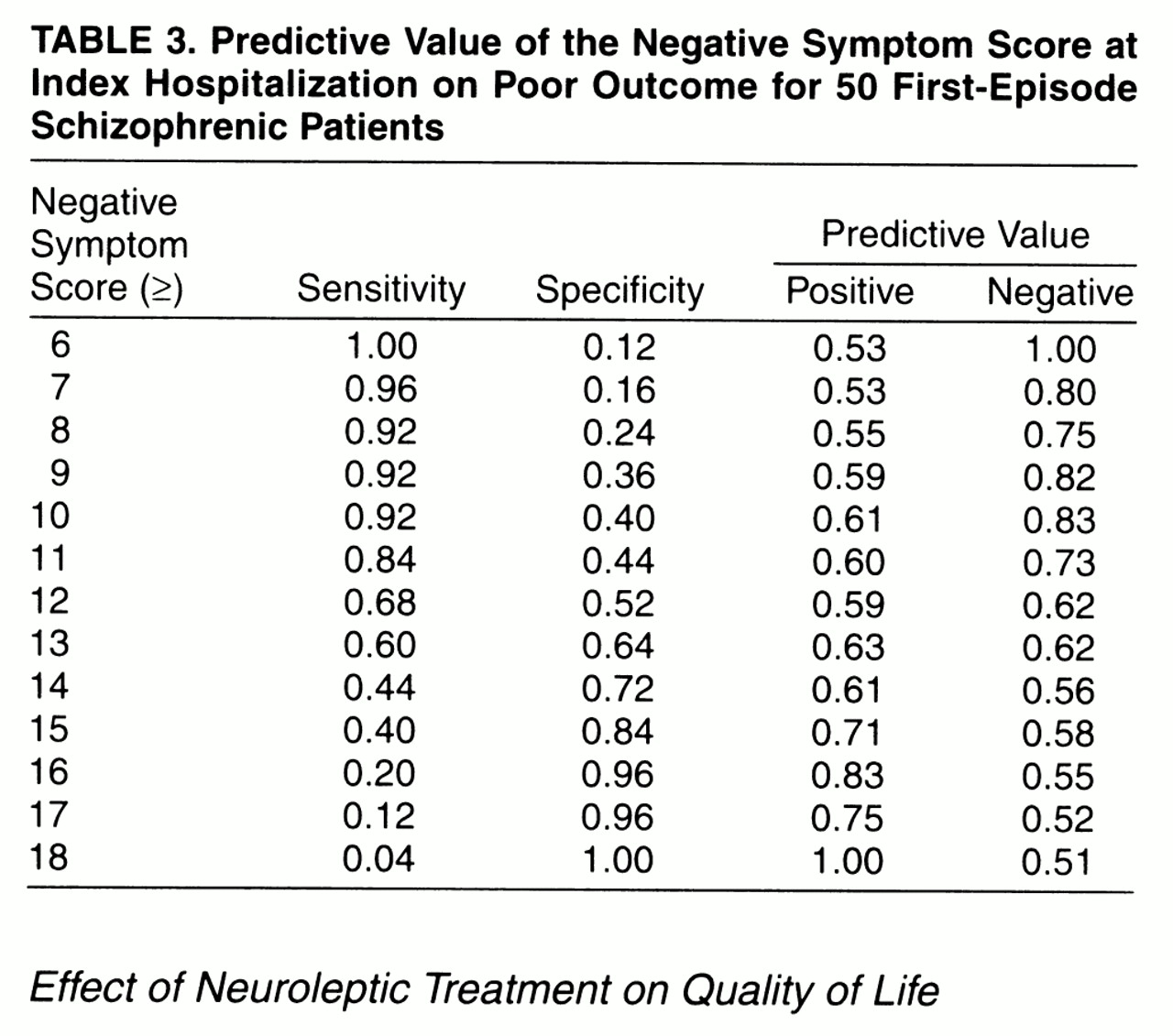

Predictive Value of the Negative Symptom Dimension on Poor Outcome

Table 3 shows the sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values for a range of threshold negative symptom dimension scores in predicting poor outcome. A negative symptom score of 13 or greater provided the best combination of sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values on predicting poor outcome. Given an intake negative symptom score of 13 or greater, the probability of a poor outcome at 2 years was 63%. If a subject had a negative symptom score of less than 13, the probability of a good outcome was 62%.

Effect of Neuroleptic Treatment on Quality of Life

There were no statistically significant correlations between total duration of neuroleptic medication treatment (r values=0.009 to 0.13, df=48, p values >0.36) or duration of atypical neuroleptic treatment (r values=0.03 to 0.16, df=48, p values >0.28) and quality of life measures. When we compared the 11 subjects who had atypical neuroleptic treatment with the other 39 subjects who only had typical neuroleptics, we found no statistically significant differences between the two groups in intake symptom measures, quality of life measures, or total duration of neuroleptic treatment (t values=1.42 to 0.14, df=15 to 24, p values>0.17). Subjects with poor outcome were not any more likely than the rest of the group to have been treated with a typical neuroleptic during the follow-up period χ2=1.05, df=1, p<0.31).

DISCUSSION

The relationship between symptoms and outcome in schizophrenia has been extensively studied, but the results remain inconclusive

(35,

36). In the literature, there is general consensus that symptoms ascertained in the chronic stable state predict concurrent functioning

(37-

42), i.e., higher residual levels of positive and negative symptoms correlate with poorer functioning. However, findings regarding the predictive value of symptoms ascertained in severely or acutely ill patients have been more mixed. While some investigators have reported that such symptoms do not predict follow-up social disability

(1,

38,

43,

44), others have found quite the opposite results

(7,

36,

39,

45). Negative symptoms have even been associated with good short-term outcome

(2,

26). These conflicting findings may be due, in part, to the fact that the subjects in these studies, although all in an “acute exacerbation,” were in different phases of the disease. Furthermore, neuroleptic treatment, which is not uniform across these studies, may also influence the predictive values of symptoms.

Lindenmayer et al. and Kay et al.

(2,

46,

47) noted that the prognostic significance of the positive and negative syndromes may carry different meanings at different stages of the illness. Symptoms ascertained in acutely ill recent-onset patients may have better predictive validity than those ascertained during an acute exacerbation in patients who have been ill longer

(36). Although the course of schizophrenia is variable, psychotic symptoms tend to become less florid, whereas negative symptoms often predominate the chronic phase

(48). Therefore, this natural course of symptoms over time, together with the effect of maintenance neuroleptic treatment, may affect the predictive value of symptoms.

In this study, we were interested to know if the symptoms of schizophrenia, measured during the acutely disturbed state at the first psychiatric hospitalization, could predict subsequent quality of life. We examined a cohort of first-episode patients, most of whom had been neuroleptic-naive. Such a group permitted us to evaluate outcome in schizophrenia without the confounds of chronicity or prior treatment.

We found that the magnitudes of correlation with quality of life measures were generally greater in the negative symptom dimension compared with the other two dimensions. Negative symptoms moderately predicted poorer quality of life early in the course of schizophrenia, even after we controlled for the effects of the other two dimensions and premorbid functioning. The negative symptoms also had relatively greater predictive value than the other two dimensions, with one exception where there was comparable strength of association between psychotic symptoms and financial dependence. Although less than 20% of the variance in quality of life at 2 years was explained by the initial symptoms, this finding is not surprising since outcome in schizophrenia is related to many factors.

A threshold of 13 on the intake negative symptom score best discriminated the poor outcome patients in our group. However, we derived this cutoff score from a relatively small cohort of 50 subjects at a single center, and we used trained raters. This finding needs replication before generalization to the clinical setting can be made.

Nevertheless, the ability to identify around the time of initial diagnosis which patients will likely have poor outcome has advantages. Knowing that negative symptoms are a portent of poor quality of life may influence the clinician to opt for atypical neuroleptic treatment and stress the need for more intensive psychosocial interventions for patients with prominent initial negative symptoms.

Atypical neuroleptics have been shown to be more effective in reducing negative symptoms

(49-

52) and, therefore, may potentially improve outcome of patients with prominent initial negative symptoms. In this study, we did not find any differences in outcome between subjects who had received atypical neuroleptic treatment and those who had not. This may be related, in part, to the small number of subjects who had received atypical neuroleptics. Furthermore, we did not control neuroleptic treatment in this study. Subjects who had been treated with atypical neuroleptics, particularly the three who received clozapine, might have a more severe form of the illness than subjects who had been maintained on regimens of only typical neuroleptics.

Symptoms during the acute illness early in the presentation of schizophrenia have some prognostic value. The negative symptom dimension has relatively greater predictive value than the other two symptom dimensions. Severe negative symptoms at the time of first hospitalization may be a portent of poor outcome. In general, the psychotic and the disorganized symptom dimensions do not appear to predict subsequent quality of life.