While rates of current syndromal depressive disorders are lower among HIV-infected patients than initially believed

(1), depression is nevertheless the most commonly observed axis I disorder in prevalence studies of homosexual men

(2–

5), intravenous drug-using men and women

(6,

7), and, except for hypoactive sexual desire disorder, for non-drug-using women

(8,

9). Lifetime rates of major depression were substantially elevated compared to general population rates in several studies of both HIV-positive and HIV-negative homosexual men

(1), suggesting a vulnerability to subsequent episodes.

Treatment of depression among patients with HIV illness has received little systematic study, as is true more generally of medically ill depressed patients

(10). Apart from our group’s placebo-controlled study of imipramine

(11), unpublished studies or those in press include placebo-controlled trials of imipramine

(12,

13), fluoxetine with support group

(14), and paroxetine and imipramine

(15). Small open studies of fluoxetine

(16,

17), paroxetine

(18), sertraline

(19), dextroamphetamine

(20), and nefazadone (A.J. Elliott, unpublished data, 1998) also have shown clinical benefit. Overall, response rates to active drug ranged from 45% for 11 patients treated with paroxetine to 80% for 25 patients treated with imipramine

(15), with robust placebo responses up to 48%

(14) and significant attrition up to 55% in Elliott et al.’s 1998 trial

(15).

The largest placebo-controlled trial of antidepressant medication for HIV-positive depressed patients published to date is the study of imipramine that our group conducted between 1989 and 1992

(11). In that study, 97 patients were randomized and 80 completed a 6-week trial; response rates were 74% for imipramine and 26% for placebo. Despite this robust drug effect, by the end of 6 months more than one-third of the responders had discontinued imipramine because of troublesome anticholinergic side effects such as dry mouth, fatigue, and muscle aches.

Although the empirical evidence to date is mixed, some investigators have found an association between depression and immunosuppression

(23), as well as between depression and more rapid HIV illness progression

(24); it thus seemed conceivable that treating depression may have a positive effect on measures of immune status. Conversely, in treating patients with vulnerable immune systems, there is the concern that a medication may have an adverse negative (immunosuppressive) effect. Although we did not observe either effect in the imipramine study, there are no data with respect to fluoxetine.

In view of the foregoing, we designed a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine treatment for depressed HIV-positive patients in order to address three questions: Is fluoxetine superior to placebo in treating DSM-III-R/DSM-IV depressive disorders in the context of HIV illness? Is severity of immunosuppression associated with treatment response rate? Is treatment with fluoxetine associated with changes in CD4 cell counts?

METHOD

Subjects

Study inclusion criteria required patients to be between ages 18 and 70, to have known their seropositive HIV status for at least 2 months, and to be physically healthy except for HIV-related conditions. Those with an AIDS-defining condition had to be in treatment with a primary care provider who agreed to their study participation. Psychiatric criteria included a DSM-IV diagnosis of major depression or dysthymia or both. Psychiatric exclusion criteria included a history of non-substance-induced psychosis or bipolar disorder, current (past 6 months) substance use disorder, current panic disorder, current risk for suicide, or significant cognitive impairment that would preclude adherence to the study protocol. In addition, use of another antidepressant within 2 weeks before study entry, or initiation of psychotherapy within the past 4 weeks, was grounds for exclusion. Medical exclusion criteria included HIV wasting syndrome, significant diarrhea, or unstable health (onset of new opportunistic infection within the past 6 weeks). Concurrent HIV medications were permitted and noted. Study enrollment took place between January 1993 and November 1996. All patients provided written informed consent to participate in this protocol, approved by the institutional review board, after the risks and benefits of study participation and nonparticipation were explained.

Measures

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (and later DSM-IV) (SCID) (25)

The psychotic screen, substance use disorder screen, and mood and anxiety disorder modules were administered. We began to use SCID for DSM-IV early in 1994, since the criteria for major depression and dysthymia are essentially similar.

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

We used the 21-item structured interview developed by Williams

(26). Two subscales, consisting of five items describing affective symptoms and eight items describing vegetative symptoms, were used to address possible confounding of HIV and vegetative depressive symptoms.

Clinical Global Impression (CGI) (27)

Weekly global ratings of improvement since baseline were made by the study psychiatrist on a 7-point scale (1=very much improved, 7=very much worse). Only patients with scores of 1 or 2 (very much or much improved) were classified as responders. The CGI was used as the major outcome variable in rating clinician assessment of clinical improvement at study endpoint.

Brief Symptom Inventory (28)

This is a 53-item self-report scale drawn from the SCL-90, scored on a 5-point severity scale (0=not at all, 4=extremely). Subscales include depression and anxiety, and a global severity index is calculated. Scores represent the mean item score. Higher scores signify greater distress.

Beck Hopelessness Scale (29)

This self-rated 20-item true/false scale has a total score ranging from 0 to 20, with higher scores signifying greater hopelessness.

Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (30)

The summary form of Endicott’s scale includes 14 domains, such as economic status, housing, leisure time activities, and an overall rating, each of which is rated on a 5-point scale, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction.

Systematic Assessment for Treatment Emergent Events (31)

This modified clinician-administered structured interview assesses presence and severity of 78 health events; we selected for inclusion in this study events commonly regarded as SSRI side effects. Events absent at baseline and present thereafter are considered treatment emergent.

Lymphocyte subsets

At the time this study was initiated, CD4 cell count (absolute and percent) was considered the best marker of illness progression and remains a standard index

(32). This was our dependent variable in measuring effects of fluoxetine on immune status. A commercial laboratory (then known as Metpath, now Quest, Teterboro, N.J.) performed the assays.

Illness stage

Patients were categorized according to the classification of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(33) as asymptomatic (CD4 cell count over 200 cells/mm3 and no symptoms), symptomatic (CD4 cell counts between 200 and 500 and symptoms past or current but no opportunistic infections), or as having an AIDS-defining condition (CD4 cell count under 200, past or present AIDS-defining opportunistic infection or malignancy, or both).

Clinician and self-rating scales were administered and laboratory tests were conducted at study baseline, at weeks 4 and 8, and at termination of treatment at week 26 or study endpoint if sooner.

Statistical Analyses

Chi-square tests were used for analysis of categorical data. The Fisher exact test was substituted for chi-square for expected cell size less than 5. For continuous measures, t tests were used, with paired t tests to assess change over time. A hierarchical multiple regression analysis was performed to identify the effect, if any, of type and duration of treatment on CD4 cell count changes over time. All tests were two-tailed.

Procedure

Initial evaluation by licensed clinical psychologists included medical and psychiatric history, neuropsychological screen, diagnostic assessment using SCID modules for depression and anxiety, and medical screening including blood work for complete blood count including lymphocyte subsets, blood chemistry tests, and thyroid panel. Primary care providers were sent letters asking whether there were any medical contraindications to their patients’ participation and whether they agreed to such participation. After completion of screening, eligible patients returned for the baseline study visit, when the informed consent procedure was conducted and a confirmatory diagnostic evaluation was performed by the study psychiatrist.

Patients were randomly assigned through computer-generated blocks of six in a 2:1 ratio to fluoxetine or placebo and were seen weekly by the study psychiatrist for 8 weeks. The dose schedule was fixed at 20 mg/day for the first 4 weeks and was thereafter increased by 20 mg/day biweekly in the absence of clear-cut clinical improvement and significant side effects. Medication was dispensed weekly, and doses were taken in the morning. Clinical response at week 8 was defined by two criteria: CGI rating of 1 or 2 (very much or much improved) and decline in Hamilton depression scale score of at least 50% plus a total Hamilton score of 8 or less at week 8. The study was designed to follow patients for an additional 18 weeks in order to observe duration of effect among responders and possible impact of fluoxetine on laboratory markers of immune status, which were measured at baseline, week 8, and study endpoint.

RESULTS

Subjects

Of the 120 patients enrolled in the study, 81 (68%) were randomly assigned to fluoxetine and 39 to placebo. Eighty-seven (73%) completed the study. For the total enrolled group, average age was 39 years (SD=9, range=22–64). Twenty percent were African American, 15% Latino, and 65% white. All but three were men, 88% had at least some post-high-school class work, and 46% were college graduates. Thirty-six percent were receiving disability benefits. In terms of medical status, 51% had an AIDS-defining condition; mean CD4 cell count was 295 cells/mm3 (SD=287, range=3–1081; 47%: <200 cells/mm3; 35%: 200–500 cells/mm3; 18%: >500 cells/mm3). Mean number of months since testing HIV seropositive was 53 (SD=32). Mean number of HIV medications was 2.5 (SD=0.7, range=0–11), and 47% were taking one or two antiviral medications (only three patients were taking protease inhibitors at study baseline since the study was conducted before their approval). Risk factors were sex with men (94%) and needle sharing associated with intravenous drug use (6%).

In terms of psychiatric status at baseline, 95% had major depression (37% single episode, 35% recurrent, 23% with dysthymia), 4% had dysthymia only, and one patient had minor depression. Mean baseline Hamilton depression score was 18.6 (SD=4.8). Modal duration of current episode was 1–5 years (52%); 16% had had chronic depression longer than 5 years. Only 6% had been depressed less than 3 months at study baseline. Sixty-two percent had received psychotherapy, antidepressants, or both. At study entry, seven patients were in therapy; five were randomly assigned to fluoxetine and two to placebo, with one being a placebo responder.

Dropouts

Of the 33 dropouts, 24 had been randomly assigned to fluoxetine and nine to placebo (χ2=0.7, df=1, n.s.). Six patients dropped out because of side effects (one developed a rash that may have been an allergic reaction); 16 did not show up for appointments and could not be contacted, one started receiving fluoxetine from his primary care physician, and nine discontinued or were administratively removed because of AIDS-related conditions (N=4), worsening mood symptoms (N=2), or current substance abuse (N=3). One patient tasted his medication in order to break the blind.

Patients who completed the study (N=87) were compared with all 33 dropouts. Completers were more likely to have a more chronic and more severe depressive illness. Their Hamilton depression mean scores were higher on the total scale (mean=19.4, SD=4.8, versus mean=16.5, SD=3.9) (F=9.7, df=1, 119, p<0.01) and on the cognitive subscale (F=6.6, df=1, 116, p<0.01). Two-thirds (N=57 of 87) of the completers had a chronic or recurrent depression, compared to 44% (N=15 of 34) of the noncompleters (χ2=4.6, df=1, p<0.05). The only other difference was ethnicity: Latinos were more likely than black or white patients to drop out (50% versus 13% and 28%, respectively) (χ2=7.2, df=2, p<0.05).

Treatment Outcome: Fluoxetine Versus Placebo

At week 8, 74% (N=42 of 57) of study completers randomly assigned to fluoxetine were rated responders, compared to 47% (N=14 of 30) assigned to placebo (χ2=6.3, df=1, p<0.05). When this analysis was repeated excluding patients with dysthymia and depressive disorder not otherwise specified, results remained significant (χ2=4.2, df=1, p=0.04). In an intention-to-treat analysis, in which all randomized patients were included, 57% (N=46 of 81) of fluoxetine patients and 41% (N=16 of 39) of placebo patients were rated as responders (χ2=2.62, df=1, n.s.). Mean dose of fluoxetine at week 8 was 37 mg/day (SD=14); 90% were taking 20 or 40 mg/day. There was no difference in mean daily dose between responders (35 mg/day, SD=12) and nonresponders (40 mg/day, SD=14) (t=1.6, df=64).

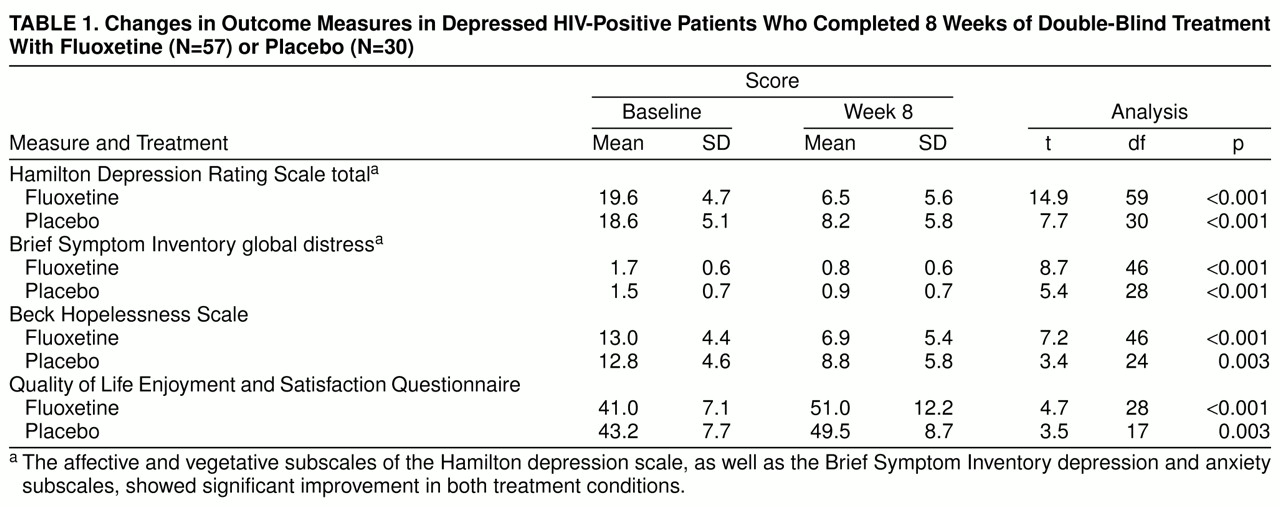

As shown in

table 1, patients in both treatment conditions showed statistically significant improvement over time on all study measures.

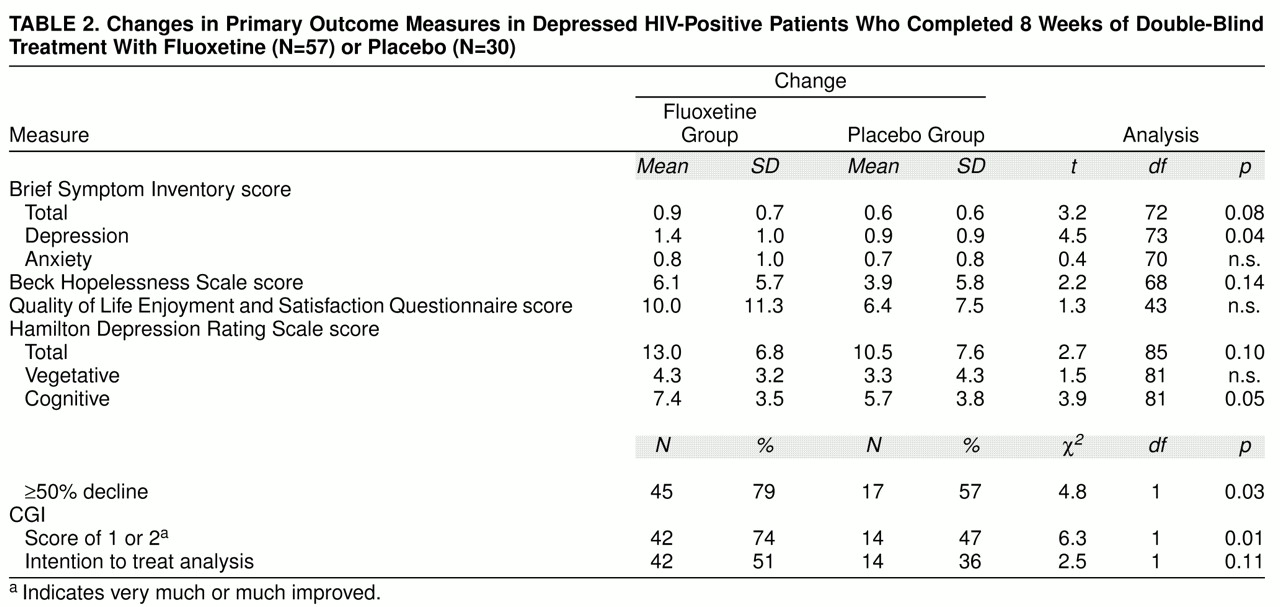

table 2, showing magnitude of change, indicates that this improvement was similar across treatment groups for most outcome measures. Clinician-rated cognitive symptoms of depression, clinical global ratings, and self-rated depressive symptoms revealed a treatment group difference favoring fluoxetine. In addition, a greater proportion of fluoxetine-treated patients showed at least a 50% decline in Hamilton depression scale scores over time.

Depression Severity and Chronicity and Treatment Outcome

No differences in baseline measures of depressive severity were found between responders and nonresponders in either treatment group. Among fluoxetine patients who completed the study, mean baseline Hamilton depression scores were 19.8 (SD=5.1) for the 42 responders and 19.6 (SD=3.1) for the 15 nonresponders (t=0.15, df=55, n.s.). Among placebo patients who completed the study, mean baseline Hamilton depression scores were 19.4 (SD=5.6) for the 14 responders and 18.8 (SD=5.0) for the 12 nonresponders (t=0.28, df=24, n.s.). Similarly, no baseline differences on the Global Severity Index or the depression subscale of the Brief Symptom Inventory were observed for either treatment group (data not shown).

Chronicity of depression has been associated with a poorer response rate to antidepressant treatment, although this may simply reflect a lower nonspecific response rate among chronically depressed patients

(34). We classified our patients as chronic (dysthymia with or without major depression, or major depression with recurrent episodes) or nonchronic (first episode of major depression) and examined response rate within treatment conditions. In neither condition was there a significant difference in response rate associated with chronicity (fluoxetine: N=57, p=0.34; placebo: N=30, p=0.72, Fisher’s exact test).

Side Effects

Half the group reported treatment-emergent side effects (absent at baseline, present thereafter) at one or more visits. Six patients, all taking fluoxetine, discontinued treatment because of side effects (sleepiness, diarrhea, insomnia, upset stomach, overstimulation, rash). Fifty percent of patients taking placebo and 50% taking fluoxetine reported at least one treatment-emergent side effect during the trial. No side effect was reported significantly more often by patients in either treatment condition, except for headache, reported by 12 fluoxetine patients and no placebo patients. There was no difference in mean number of side effects reported by treatment condition (fluoxetine: mean=1.4, SD=2.0; placebo: mean=1.3, SD=1.8) (t=0.1, df=118), and patients with lower CD4 cell counts did not report more side effects. The most frequent side effects were gastrointestinal symptoms including upset stomach and diarrhea (26%), overstimulation and nervousness (18%), sleepiness and appetite and weight loss (13% each), dry mouth (11%), and sexual dysfunction (10%). Most of these were rated mild and were transient; none was reported on two occasions by more than four patients. No serious side effects were reported.

Treatment Status at Week 26

Of the 42 fluoxetine responders at week 8, 28 (67%) continued to take the medication throughout the 26-week study, and all maintained their response. Adjunctive medications (testosterone, psychostimulants, lorazepam) were added to the regimens of five of these patients. Of fluoxetine responders who discontinued medication after week 8, four did so because of geographical relocation, five to change to another medication to reduce side effects, and the remaining patients for other reasons.

Six patients who had only a partial response to fluoxetine at week 8 continued to take medication throughout the 26-week study. By week 16, four responded, of whom one had adjunctive amphetamine added and two had a fluctuating mood course throughout the period of observation. Among the 16 placebo nonresponders, 10 initiated fluoxetine treatment; seven (70%) were rated as responders at week 16. Six of the 14 placebo responders started fluoxetine treatment to further improve their mood; all but one reported additional benefit.

Severity of Immunosuppression and Treatment Outcome

We compared response rates of patients with CD4 cell counts under 200 with response rates of other patients, within treatment condition, to determine whether those with severe immunosuppression responded as well as others. We found no difference in response rates, side effects, or attrition. Among fluoxetine patients, response rates were 76% among patients with CD4 cell counts under 200 and 70% for those with CD4 cell counts over 200 cells/mm3 (χ2=0.22, df=1, n.s.). For placebo patients, response rates were 57% for patients with CD4 cell counts under 200 cells/mm3 and 33% for those with CD4 cell counts over 200 (χ2=1.7, df=1, n.s.).

Effect of Fluoxetine on CD4 Cell Count

Among those randomly assigned to fluoxetine, CD4 cell count did not change significantly from baseline (mean=306 cells/mm3, SD=280) to study endpoint (mean=277, SD=245), an average of 18 weeks later (t=1.5, df=52). Similarly, CD4 cell count did not change among those taking placebo (baseline mean=248 cells/mm3, SD=203; endpoint=250, SD=185) after an average of 12 weeks (t=0.1, df=24).

To determine whether duration or kind of treatment influenced CD4 cell count, we performed a multiple regression analysis, entering baseline CD4 cell count first. The dependent variable was endpoint CD4 cell count. Baseline CD4 cell count was the only significant variable, accounting for 76% of the variance in endpoint CD4 count. Together, duration and type of treatment contributed only an additional 1% of variance; neither was a statistically significant predictor.

DISCUSSION

While our analysis of patients who completed the study showed a statistically and clinically significant advantage for fluoxetine (74% versus 47%), the intention-to-treat analysis showed no significant difference (57% versus 41%), largely because of the high placebo response rate. With respect to drug and placebo response and attrition, our results are comparable to those reported in other double-blind antidepressant studies with HIV-positive patients, except for our own

(12–

19). However, these results are in striking contrast to the findings of our randomized, placebo-controlled imipramine study

(11) at the same site and with the same clinical team 3 years earlier, which found among study completers the same drug response rate (74%) but a modest placebo response rate of 26%. Neither study found a difference in dropout rate or response rate associated with more severe HIV illness, and side effects were not more frequent or troublesome in patients with late-stage illness. Both studies failed to detect a differential response rate as a function of the chronicity of depression or severity of HIV illness.

In terms of safety, neither study found a negative effect of antidepressants on CD4 cell counts, a standard measure of immune status. In the aggregate, CD4 cell counts did not decline significantly over time regardless of treatment condition, and no positive effects on CD4 cell count were observed.

For clinicians working with HIV-positive patients, there may be concern about possible interactions with fluoxetine (and other antidepressants) and protease inhibitors. All protease inhibitors and most psychotropic drugs are metabolized by means of the cytochrome P450 oxidase system, primarily the 3A/4 isoform, with the 2D6 isoform the secondary metabolic pathway

(35). Theoretically, interactions may accelerate or inhibit the clearance of either drug. However, bupropion is the only antidepressant listed as contraindicated by a single protease inhibitor, ritonavir, and this was done on a presumptive rather than empirical basis. There are no research data regarding adverse events associated with any SSRI and protease inhibitors; however, in the clinical practice of primary care physicians and in our ongoing research studies with fluoxetine, no adverse clinical effects have been observed in relation to any of the 13 antiretroviral medications currently marketed.

Attrition of 27% was somewhat high but was comparable to that reported in other studies of HIV-positive patients

(15). It is our clinical impression that as more antiretroviral and prophylactic HIV medications are being prescribed, patients are increasingly reluctant to add psychotropic medications as well. This has slowed enrollment and may contribute to attrition.

What might account for the difference in placebo response rate between the two studies? First, there has been a general trend over time in placebo-controlled clinical trials for placebo response rates to increase (S.N. Seidman, unpublished data, 1998); our findings may simply be part of a larger pattern. We might also conjecture that the milder and fewer side effects of fluoxetine compared to imipramine might better have preserved the blind for both doctor and patient. In terms of medical and sociodemographic characteristics, in the fluoxetine trial patients were sicker (51% versus 38% had an AIDS-defining condition), the proportion of ethnic minority patients was higher (35% versus 17%), and more received disability payments (36% versus 14%). A methodological difference also may have contributed to the observed difference in nonspecific effect: in the imipramine study, physical examinations were conducted at our clinic to rule out medical contraindications to study participation. In the fluoxetine study, we instead wrote each patient’s primary care physician, asking him or her to state that there were no medical contraindications and to approve the patient’s study participation. With patients, we discussed the importance of regular medical care and of the doctor-patient relationship. For patients having problems with their medical care, we suggested clinics or private doctors we knew provided superior care. We may thus have been perceived as more involved in the patient’s total care, which may have had a nonspecific benefit.

Finally, the difference in study design between the two trials may have influenced outcome assessment. In the imipramine study, responders (at week 6) were maintained double-blind on the same treatment for an additional 6 weeks so that the outcome “call” had direct practical consequences. In contrast, the fluoxetine trial ended after 8 weeks, and the code was then broken. At that point, five of the 14 placebo responders requested a trial of fluoxetine despite their reported and self-rated improvement. If these five “responders” had participated in a trial with a double-blind maintenance phase, it is possible that they would have been considered “nonresponders.” The placebo response rate then would have been 31%, equivalent to that of the imipramine trial.

Our findings are consistent with those of others reported in the literature: while we observed a robust response to fluoxetine and a statistically significant advantage of fluoxetine over placebo in patients who completed the study, the difference was relatively modest. Approximately two patients in four improved with placebo, and an additional patient improved with fluoxetine, while one in four did not improve during the 8-week study. Whether medically ill patients diagnosed with major depression are more likely to experience a fluctuating clinical course with spontaneous improvements is an interesting possibility that has not yet been established.