Probability of Outpatient Service Use

The figure of 13.3% of National Comorbidity Survey respondents who used outpatient services is slightly higher than the 12.3% found a decade earlier in the ECA study (excluding the ECA respondents who were counted as receiving “services” in the ECA only because of talking to family or friends)

(2), which superficially suggests that there was no change in probability of outpatient service use over that time interval. There are many differences in the two surveys, however, that confound any attempt to make rigorous comparisons (for example, an unrestricted age range in the ECA but not the National Comorbidity Survey, local sampling in the ECA versus national sampling in the National Comorbidity Survey, DSM-III diagnoses in the ECA versus DSM-III-R diagnoses in the National Comorbidity Survey).

Three aspects of the ECA study design created higher estimates of outpatient service use than we found in the National Comorbidity Survey. First, the ECA study was carried out largely in urban areas. Second, the ECA had a more inclusive definition of general medical use than the National Comorbidity Survey. Third, the ECA 12-month service use estimate was based on a combination of data from three interviews (a baseline interview that asked about service use during the previous 6 months, a reinterview 6 months later that asked about service use since baseline, and a second reinterview 12 months after baseline that asked about current service use). This would be expected to reduce recall failure compared with a single interview using 12-month recall. The fact that the 13.3% National Comorbidity Survey estimate is slightly higher than the 12.3% ECA estimate, despite these three differences, implies that a comparison using the same definitions of use and same sampling frame would probably show a clear increase between the early 1980s and early 1990s.

Two other sector-specific differences between the National Comorbidity Survey and the ECA are also worthy of note. First, general medical use was much lower in the National Comorbidity Survey (3.9%) than the ECA (6.4%). The ECA estimate implies that the general medical sector was the most common point of contact for outpatient psychiatric help-seeking (53% of all people in treatment seen in this sector), but the National Comorbidity Survey estimate implies that the rate of use of the general medical sector for psychiatric help was much lower (29%). This difference could be due to the three-wave ECA design having an especially strong effect in reducing recall failure of general medical visits. Or it could be because the question about general medical use was broader in the ECA than the National Comorbidity Survey. ECA respondents were asked whether they “talked to” a general medical provider “about” psychiatric problems, and they were asked whether they “went to” other providers “for help with” these problems. The National Comorbidity Survey asked the more narrow question of whether they went for psychiatric help to each of the providers in a comprehensive list that included, among others, both general medical providers and mental health specialists.

The National Comorbidity Survey presumably underestimated general medical use, in view of the fact that many people with emotional problems seek help in the general medical sector for primary somatic complaints

(19,

20) and might not have gone “for help with” emotional problems even though these problems are mentioned as secondary complaints. However, if their physicians treated the emotional problems, the patients would be told to come back for a follow-up visit 2–4 weeks after starting their psychotropic medications to check on side effects and treatment response. These follow-up visits would be “for help with” emotional problems and would, therefore, be picked up in the National Comorbidity Survey question. This means that the only patients missed because of the wording of the National Comorbidity Survey question would be those who initially presented primary somatic problems and either were not treated for their secondary emotional problems or failed to make follow-up visits for treatment of their emotional problem. Exclusion of these patients is probably appropriate because it is difficult to think of them as truly having been in treatment for their emotional problems.

The ECA, in comparison, counted patients as being in treatment for their emotional problems if they told their doctor about these problems. As noted by Mechanic

(21), this leads to substantial overestimation of general medical treatment of emotional problems because many of the patients who told their doctors about these problems did not receive treatment. Given the importance of primary care physicians as gatekeepers in managed care, future surveys need to resolve this uncertainty by combining the ECA and National Comorbidity Survey approaches to learn if respondents talked to a general medical doctor about psychiatric problems, whether this was the primary purpose of their visit, and whether they received treatment from the doctor for these problems. It is also important that future studies address the fact that primary care doctors sometimes prescribe psychotropics for patients they diagnose as somatizers without telling the patients they might have emotional problems. This hidden treatment of emotional problems might be very common

(22,

23). If so, not only the National Comorbidity Survey but also the ECA could have substantially underestimated the true extent of general medical treatment of emotional problems.

A second difference between the National Comorbidity Survey and the ECA in sector-specific outpatient service use concerns self-help. Although 3.2% of National Comorbidity Survey respondents (accounting for more than 40% of all visits) reported participation in self-help groups, only 0.7% of ECA respondents did so (19% of all visits)

(2,

3). The possibility has been raised that this difference could be due to the broader wording of the question about self-help use in the National Comorbidity Survey than the ECA. The National Comorbidity Survey asked respondents whether they went to a self-help group “for problems with your emotions or nerves or your use of alcohol or drugs,” while the ECA asked respondents if they went to “someone at a self-help group like Alcoholics Anonymous, etc.” It is conceivable that the ECA respondents interpreted this question narrowly to be asking exclusively about use of self-help groups for substance problems. If so, there might not have been any real change in self-help group use in the United States in the decade between the times the ECA and the National Comorbidity Survey were carried out.

We suspect, however, that the dramatically higher prevalence of reported self-help use in the National Comorbidity Survey than the ECA is due to more than a difference in the question wording. There are two reasons for this suspicion. The first is that the ECA question about self-help use was part of a larger series of questions introduced with the statement, “Now I’m going to read you a list of different kinds of places and people where someone might get help for problems with emotions, nerves, drugs, alcohol, or their mental health.” Questions in the series repeatedly asked respondents whether they saw various types of providers “for help with any of these problems” and intermittently repeated the entire stem by asking about seeing various types of providers “for help with problems with your emotions, nerves, drugs, alcohol, or your mental health.” The self-help question happened to be one of the questions in which this phrase was missing. However, we believe that it is likely, especially in the light of the fact that self-help participants reported attending a mean of 25 meetings a year, that such participants would think to report that they attend such a group for emotional problems, even though the only example given in the question was Alcoholics Anonymous.

The other reason we believe that the much higher prevalence of self-help use in the National Comorbidity Survey than the ECA is due to more than differences in question wording is that this higher prevalence estimate is consistent with a number of independent data sources. These include the observations of clinicians of a great increase in patients who seek help in self-help groups

(24), an increase in self-help clearinghouses to handle the growth of self-help groups beginning in the 1980s

(25–

27), and the fact that a recent national survey

(28) carried out after the National Comorbidity Survey found evidence based on synthetic cohort analysis of an enormous increase in self-help group participation in cohorts born after World War II.

The Relationship Between Need and Outpatient Service Use

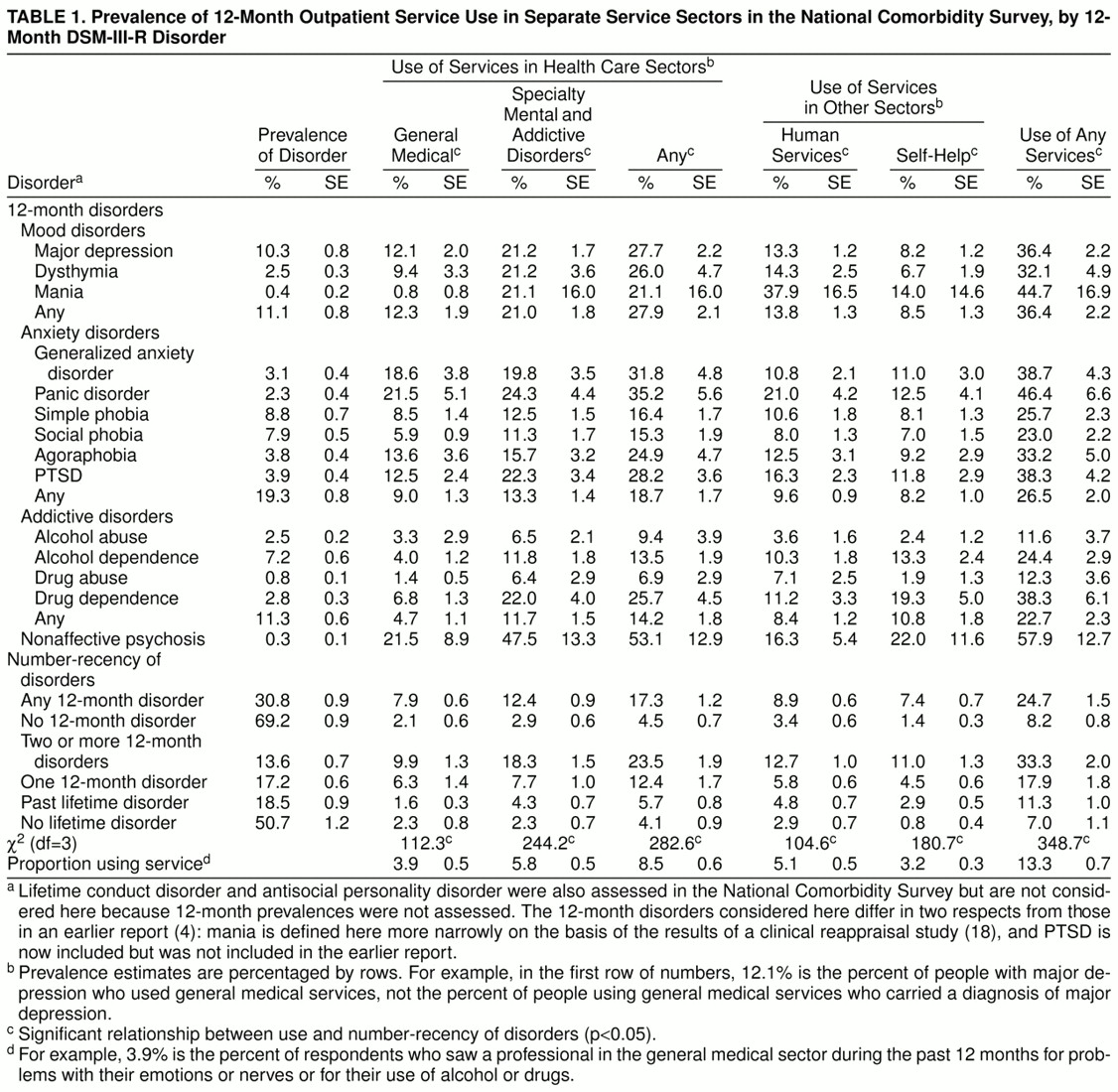

Only a minority of the National Comorbidity Survey respondents who met criteria for a disorder in the 12 months before interview reported any 12-month outpatient treatment. This is consistent with findings of previous studies

(2,

5), as is the finding that nearly half of the people who received treatment did not carry any of the disorders assessed in the National Comorbidity Survey

(2). Earlier similar results raised concerns that a high proportion of mental health services might be going to people with low need

(2,

3).

The debate about the relationship between diagnosis and need for treatment is complex and goes well beyond the focus of this report

(29–

31). However, two points are worth noting in response to the concern that treatment of many patients who fail to carry a DSM diagnosis is indicative of inappropriate treatment of people with low need. The first is that neither the National Comorbidity Survey nor earlier studies assessed the full range of DSM disorders. The second is that despite the fact that the National Comorbidity Survey assessed only a small proportion of all DSM disorders, nearly three-fourths of the visits reported in the National Comorbidity Survey were made by people who met criteria for one or more of the 12-month disorders and that close to 90% were made by people with at least one lifetime disorder.

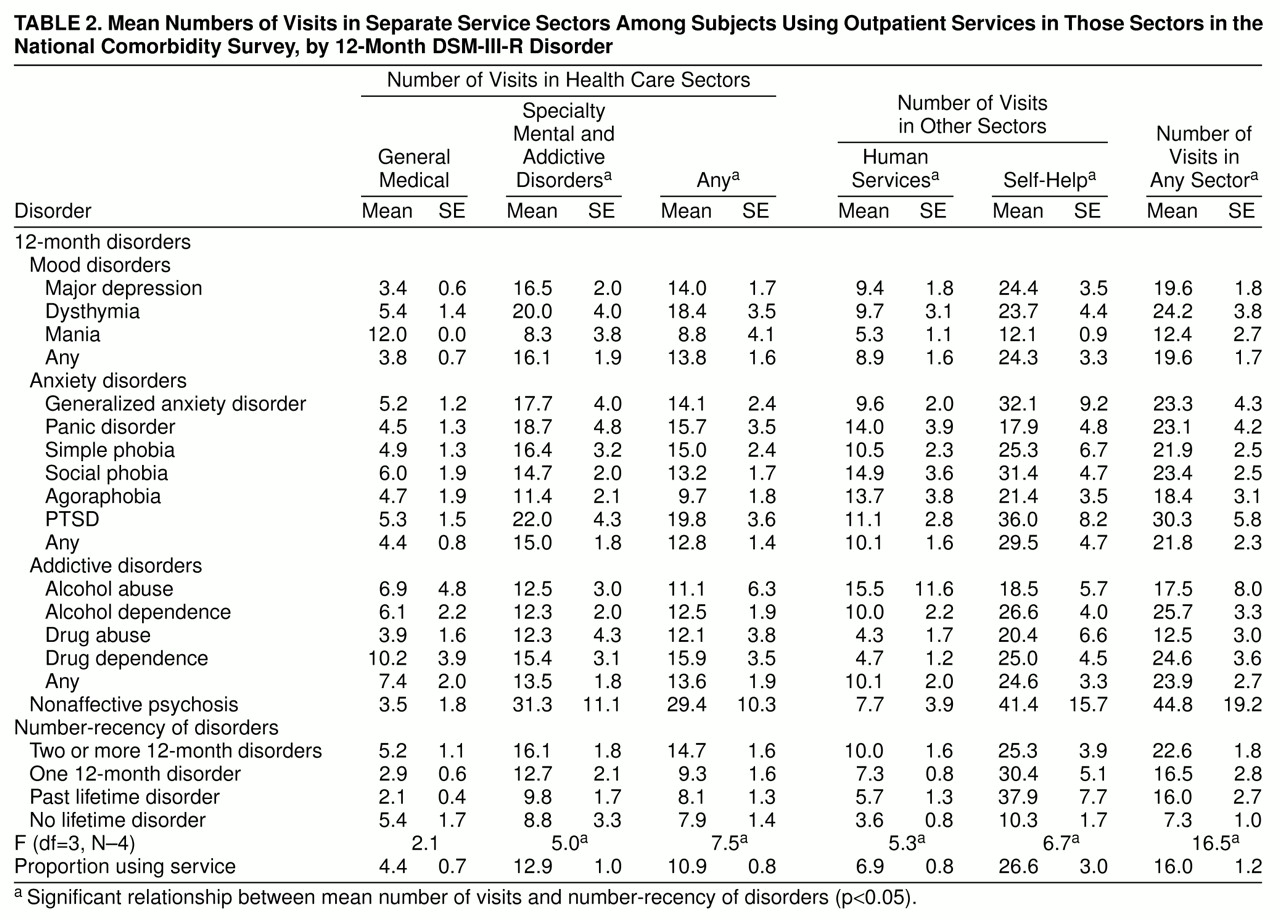

We have no way of knowing which, if any, of the DSM disorders assessed in the National Comorbidity Survey were the primary reason for seeking treatment. Nonetheless, the findings that seriousness and comorbidity of disorders are strongly related both to probability of service use and to number of visits are consistent with findings in the ECA study

(2,

3) and the RAND Health Insurance Experiment

(5). However, there is one important exception to this general pattern—no statistically significant relationship was found between number-recency of disorders and duration of treatment in the general medical sector (

table 3). This is identical to a result found in the RAND Health Insurance Experiment

(5). Moreover, a related National Comorbidity Survey finding demonstrated that the gradient of the relationship between number-recency of disorders and probability of use was much less steep in the general medical sector than the specialty sector (ratios of 4.3 and 8.0, respectively, for probabilities of use in the highest versus lowest number-recency categories).

This last result could be due, at least in part, to the fact that the National Comorbidity Survey underestimated general medical use in the way described above. Furthermore, the fact that “diagnosis” is not the same as “need for treatment” means that we cannot conclude from these results that allocation of resources is less closely tied to need in the general medical sector than other sectors. Nor can we legitimately make inferences from these cross-sectional naturalistic data about the driving force behind the observed patterns. Nonetheless, these results do raise a question for future research regarding differences in the determinants of variation in treatment intensity across treatment sectors.

A related finding is the statistically significant relationship in the treatment subsample, as shown in

table 1, between complexity of disorder (as indicated by a diagnosis of nonaffective psychosis or comorbidity) and treatment in the specialty versus nonspecialty sectors. This pattern is far from consistent, however, as indicated by the fact that the relative prevalences of treatment in the general medical and specialty sectors are greater for panic disorder than social phobia despite the fact that the impairment associated with panic is almost certainty greater than that associated with social phobia. The finding that the disorders of the patients seen by specialists are, in the aggregate, more complex than those seen in other service sectors contradicts some previous studies that have found only weak differences in the seriousness and complexity of cases seen in general medical versus specialty settings

(2,

5) but is consistent with other studies

(32–

35). The documentation of this association in a nationally representative general population survey that includes service use in both the medical and nonmedical sectors highlights the importance of making provisions for specialty care in the triage systems currently evolving as part of managed care.

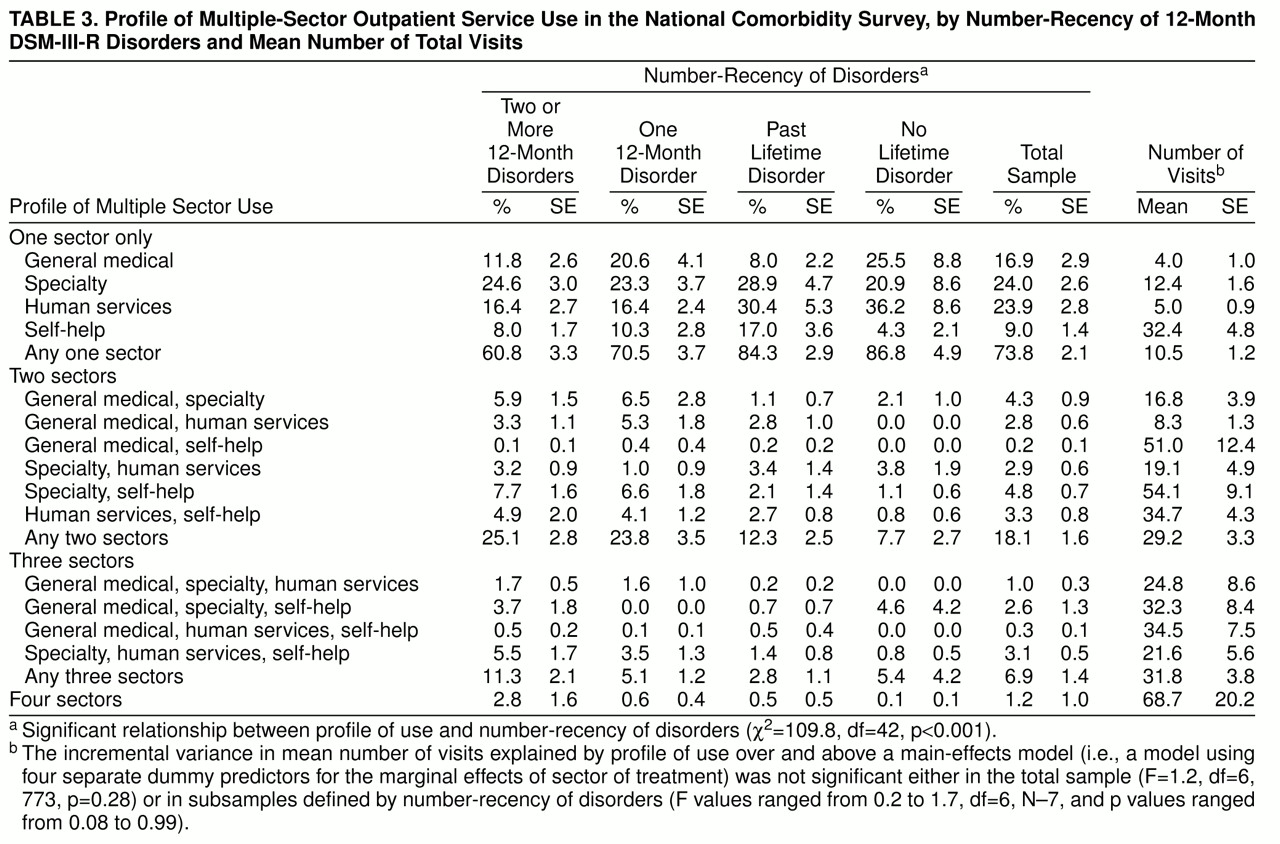

Use of Multiple Sectors

Over one-fourth of all outpatients and nearly 40% of outpatients with comorbid disorders were seen in more than one service sector. The self-help sector was most likely to be used in conjunction with some other sector rather than alone—63% of those in self-help were also in some other sector, compared with 42%–50% of those in other sectors. We have no way of determining from the National Comorbidity Survey data how often this use of multiple sectors was coordinated (e.g., a primary care doctor and psychologist working together to provide joint pharmacotherapy and talk therapy) versus uncoordinated or sequential.

The question naturally arises as to whether there is some sort of offset effect associated with use of multiple sectors. This would be much easier to study if data on coordination of treatment were available. To the extent that we can get a glimpse of this issue with the available data, there appears to be no offset effect. This conclusion is based on the finding that total visits were an additive function of the number and types of sectors used.

This said, it is important to realize that those who use multiple health care sectors are likely to have greater need and/or greater motivation to pursue treatment than those who use only one sector. This means that unmeasured aspects of demand for services might exist that confound any attempt to make causal inferences from the National Comorbidity Survey data concerning the offset effect of multiple sector use. A more fine-grained descriptive analysis or an experimental analysis might find that systematic adjunctive use of self-help as part of a comprehensive specialty treatment package could reduce the number of visits to specialists. Given the enormous popularity of self-help groups in the United States today and the existence of emerging models for combined use of professional and self-help services

(36), it would seem to be an area warranting more systematic investigation.