During the past decade, clinical trials have shown that clozapine has a significantly greater impact on the symptoms of refractory schizophrenia than do conventional pharmacotherapies

(1–

9). While a recent review concluded that clozapine clearly reduces positive symptoms (e.g., hallucinations, delusions)

(7), its specific efficacy for negative symptoms (e.g., blunted affect, motor retardation, lack of motivation), and especially for primary negative symptoms (those unrelated to positive symptoms, depression, or extrapyramidal side effects), is controversial

(8,

10). Uncontrolled studies have suggested that clozapine treatment is associated with substantial improvements in social functioning and quality of life and with reduced suicidality

(4,

11,

12); and benefits in quality of life have been demonstrated in a recent controlled trial

(9). A major advantage of clozapine is that patients experience a far lower incidence of extrapyramidal syndrome symptoms than with other antipsychotic medications

(13); and this effect has been cited as a partial explanation of clozapine’s effect on negative symptoms

(14,

15).

In a recent review of the specific effect of clozapine on negative symptoms, Carpenter et al.

(8) suggested that the observed effect of clozapine on negative symptoms is secondary to its effect on positive symptoms and, to a lesser extent, to its effect on extrapyramidal side effects. As with conventional antipsychotic medications, Carpenter et al.

(8) and others

(5,

16) maintain that improvement in positive symptoms with clozapine does not affect what has been called the deficit syndrome, a clinical subtype of schizophrenia with an especially poor prognosis. This syndrome is formally characterized by restricted affect, loss of interest, diminished sense of purpose, and low social drive, all lasting 12 months or more and not attributable to the effect of positive symptoms of schizophrenia or other symptoms such as anxiety, depression, or medication side effects

(17,

18).

Although clozapine has been shown to be effective in refractory schizophrenia, nonresponse is common, and 50%–70% of patients fail to show significant improvement with clozapine

(1–

9). It is not clear whether such nonresponders are more likely than others to meet criteria for the deficit syndrome or whether they merely failed to respond to the new medication.

In a rebuttal of the position of Carpenter et al., Meltzer

(10) reviewed several studies showing improvement in negative symptoms with clozapine therapy. However, most of these studies were uncontrolled or had small sample sizes and did not demonstrate a specific effect of clozapine on negative symptoms independent of its other effects. Meltzer also presented previously unpublished data from an uncontrolled study of a patient sample in which levels of positive symptoms were relatively low at the time of treatment initiation and in which patients treated with clozapine nevertheless showed a significant reduction in negative symptoms

(10). However, the sample size in that study was small (N=36), control group data were not included, and interaction analysis was not used.

A limitation of most previous studies of the effect of clozapine on negative symptoms is that they 1) have been based on small samples, 2) have been relatively short term in duration, 3) have not included appropriate control groups, and 4) have not used interaction analysis to test the significance of differences in subgroup response to clozapine as compared to conventional antipsychotic medications.

In this report we use data from a 12-month study of a group of patients with refractory schizophrenia to 1) compare the magnitude of treatment outcomes between clozapine and haloperidol on positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and quality of life; 2) determine whether clozapine’s impact on either positive or negative symptoms is independent of its impact on the other type of symptoms; and 3) evaluate the interaction of treatment condition (clozapine versus haloperidol) and the presence or absence of high levels of negative symptoms at baseline and the deficit syndrome.

METHOD

Data for this study were obtained from a prospective, double-blind trial in which refractory schizophrenic patients at 15 Veterans Administration (VA) medical centers were randomly assigned, over a 2-year recruitment period, to clozapine or haloperidol and treated for 12 months. The protocol was approved by a human rights committee at the Hines VA Cooperative Studies Program Coordinating Center and by human rights committees at each participating medical center, and all patients gave written informed consent.

Entry Criteria

Hospital use criteria

The study targeted a subgroup of currently hospitalized, treatment-refractory schizophrenic patients with a history of high inpatient service use, defined as at least 30 days’ hospitalization for schizophrenia during the previous year and no more than 364 days.

Clinical criteria

Clinical eligibility criteria modeled after those of Kane et al.

(1) included 1) a DSM-III-R diagnosis of schizophrenia on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID)

(19); 2) refractoriness, defined as persisting psychotic symptoms despite two documented, adequate treatment trials; 3) severe symptoms, indicated by scores on the 18-item version of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale

(20) and the Clinical Global Impression scale

(21); and 4) serious social dysfunction for the previous 2 years.

Procedure

After providing written informed consent to participate in the study and completing baseline assessments, patients were randomly assigned, within centers, to double-blind treatment with clozapine (100–900 mg/day) or haloperidol (5–30 mg/day). Dose adjustments were made as clinically indicated to maximum tolerable dose. Haloperidol-treated patients also received benztropine mesylate (2–10 mg/day) for extrapyramidal syndrome; clozapine patients received a matching benztropine placebo. Haloperidol patients participated in weekly blood counts as required for clozapine treatment.

To assess the potential effectiveness of clozapine in typical clinical practice, a predefined program of adjunctive psychotherapeutic and rehabilitative treatments was offered through a structured treatment planning module based on a comprehensive menu of locally available services. This system, described in detail elsewhere

(22), ensured that all patients were encouraged to use psychosocial services that could be of therapeutic value to them.

Symptom outcomes were assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenia, which generates separate scores for positive and negative syndrome symptoms of schizophrenia, rated on 7-point scales (1=absence of symptoms, 7=extremely severe symptoms)

(23). Positive symptoms assessed by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale include conceptual disorganization, delusions, suspiciousness, hallucinations, grandiosity, excitement, and hostility. Negative symptoms assessed by this scale include poor rapport, lack of spontaneity and flow of conversation, passivity and apathy, difficulty in abstract thinking, blunted affect, emotional withdrawal, and stereotyped thinking.

Clinical assessment interviews were conducted at 6 weeks and 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after random assignment. In this study, change was assessed as the difference between the baseline score and the 6-week, 3-month, and 12-month interviews.

Clinical Predictors of Response

To test subgroup effects, two dichotomous variables were created: one reflecting high baseline levels of negative symptoms and the other, the presence of the deficit syndrome. Negative symptom levels were dichotomized by using the median value of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale subscale for negative symptoms. Patients with the deficit syndrome were identified through a multistage procedure following principles outlined by Carpenter and colleagues

(17,

18). First, a continuous measure of severity of deficit symptoms was constructed by averaging ratings on five variables from the Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale

(24) that are identified in the literature as core features of the deficit syndrome

(17,

18): 1) lack of social initiative (the degree to which the person is active in directing his or her social interactions), 2) absence of sense of purpose (the degree to which the person has realistic, integrated goals), 3) poor motivation (ability to initiate or sustain goal-directed activity), 4) lack of curiosity (interest in surroundings), and 5) anhedonia (inability to experience pleasure or humor) (Cronbach’s alpha=0.82). These measures are all rated on a 7-point scale (0=no function in a given area, 2=major deficit, 4=moderate deficit, 6=little or no deficit). Following Kirkpatrick et al.

(18), the average score on these items was adjusted in the direction of less deficit syndrome when a depressive syndrome was diagnosed on the SCID, since this provides an alternative explanation to the deficit syndrome for the observed types of dysfunction. Patients were identified as having the deficit syndrome if they scored below the median (1.8) on the resultant scale (reflecting major problems on the relevant measures). Data were not available on the duration of the various components of the syndrome.

Crossover Patients

During the 12-month follow-up period in this study, some patients stopped taking study medication because of lack of efficacy or adverse effects and switched to other treatments. Haloperidol patients were more likely to discontinue medication because of lack of efficacy or worsening of symptoms (51% versus 15%), and clozapine patients, because of side effects (30% versus 17%) or non-drug-related reasons (55% versus 32%).

At 6 weeks 87% of patients in each group continued to take the study drug (χ2=0.01, df=1, p=0.93), but by 3 months 81% of the clozapine group continued to take the study drug as compared to 73% of the control subjects (χ2=3.9, df=1, p<0.05), and by 1 year 60% of the clozapine group but only 28% of the control subjects continued to take the study medication (χ2=43.6, df=1, p<0.0001).

While some clozapine patients received standard antipsychotic medications (including haloperidol), some haloperidol patients received clozapine. Altogether, 83 (40%) of 205 patients assigned to clozapine discontinued the medication by the 48th week of the trial and crossed to a standard antipsychotic medication (including haloperidol). Although 157 (72%) of the 218 haloperidol patients discontinued the study drug, only 49 (22%) received clozapine treatment for 4 or more weeks during the trial and would be considered crossovers.

Since the inclusion of the crossover patients in our 1-year analyses would attenuate our evaluation of predictors of response to medication, the crossover patients were excluded from the 1-year analyses presented here. Thus, all patients in the clozapine group in this subgroup were treated with clozapine for at least 48 weeks (N=122), while all patients in the control group received conventional antipsychotic medications for more than 48 weeks (N=169). Within the subgroup of patients studied at 12 months (i.e., those who did not cross over), there were no significant differences between treatment groups at baseline

(22).

Analyses

Analysis proceeded in several stages. First, chi-square and t tests were used to evaluate differences between the groups at baseline. Next, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to test the difference in outcomes with clozapine and haloperidol. These analyses tested the significance of differences between treatment groups on change in positive and negative symptoms, with adjustment for their baseline values. This adjustment was needed to address the association between the baseline level and the magnitude of the change in outcome, since patients with low symptom scores have less room for improvement than those with high symptom scores and therefore are likely to change less.

The independence of clozapine’s impact on positive and negative symptoms with respect to each other was tested by repeating the previous analyses after adding baseline and change values of the other measure as covariates.

Differential responsiveness to clozapine among clinical subgroups (patients with high negative symptoms, or on indicators of the deficit syndrome) was evaluated by analysis of the interaction of each of two dichotomous dummy-coded (0 or 1) variables representing these subgroups and treatment group assignment through use of two-way ANCOVA, with adjustment for baseline values of the outcome variables.

To address differences in outcome across sites, site was included as a class variable in all models. Standard regression diagnostics were also conducted.

RESULTS

Data presented elsewhere show that there were no significant differences between the two groups on any measure in either the as-randomized or intention-to-treat sample

(9) or in the sample, with crossover patients excluded, used for the 1-year analysis. During the first half of the trial (weeks 1–26), average doses were 430 mg/day for clozapine and 20.7 mg/day for haloperidol. During the second half of the trial (weeks 27–53), average doses were 655 mg/day for clozapine and 28.8 mg/day for haloperidol.

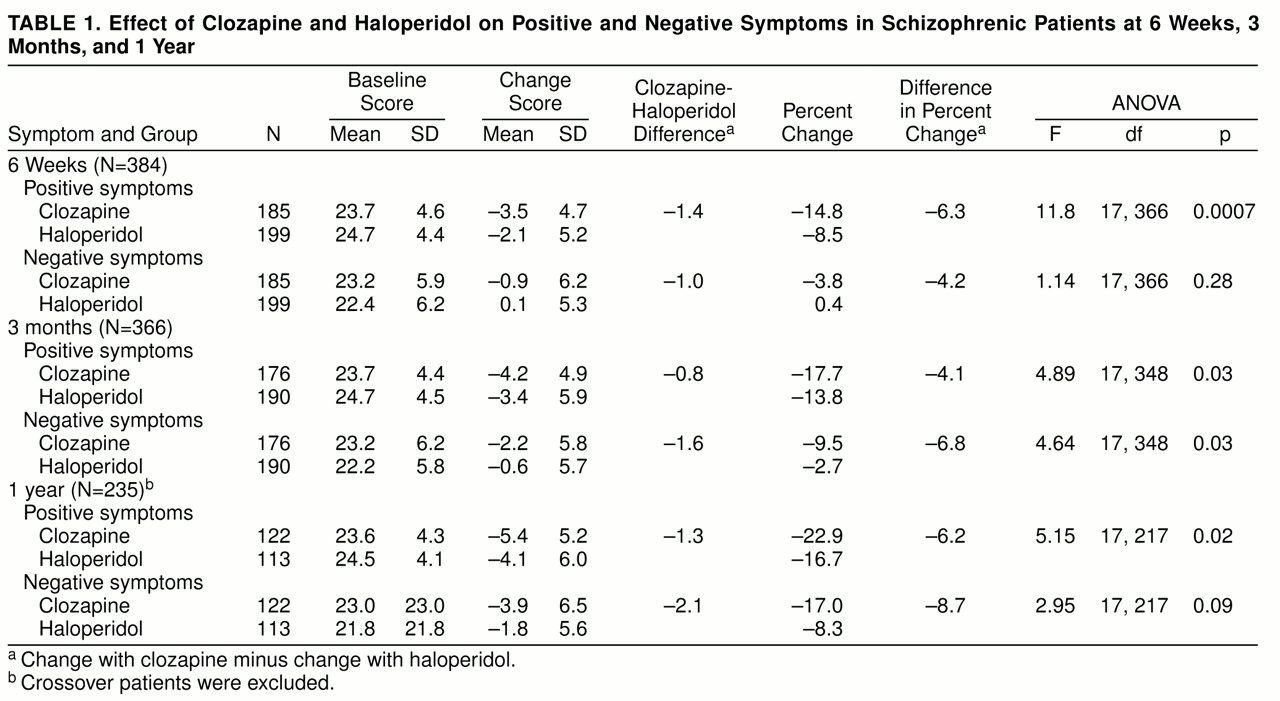

Table 1 shows that at 6 weeks patients in the clozapine group scored significantly lower than control subjects on positive but not negative symptoms; however, at 3 months patients in the clozapine group scored significantly lower than control subjects on both positive and negative symptoms. At 1 year, in the group with crossover patients excluded, patients in the clozapine group scored significantly lower than control subjects on positive symptoms but only marginally lower on negative symptoms. The effects of clozapine and haloperidol on positive and negative symptoms were not substantially different in magnitude.

When we repeated the analysis of change in positive symptoms, after covarying for the effect of change in negative symptoms, there was a persisting significant effect of clozapine on positive symptoms at 6 weeks (F=9.27, df=1, 383, p=0.003); but no effect was observed at 3 months (F=2.3, df=1, 347, p=0.13) or 1 year (F=2.5, df=1, 216, p=0.11). When we repeated the analysis of change in negative symptoms, after covarying out the effect of change in positive symptoms, we found no significant effect of clozapine on negative symptoms at 6 weeks (F=0.01, df=1, 383, p=0.93), 3 months (F=3.3, df=1, 347, p=0.07), or 1 year (F=1.7, df=1, 216, p=0.19).

Interaction analysis of both positive and negative symptoms revealed no significant interactions between treatment assignment and either baseline levels of negative symptoms or the presence of the deficit syndrome. Thus, there was no interaction between baseline level of negative symptoms and treatment group assignment in predicting change in positive symptoms at 6 weeks (F=0.03, df=1, 364, p=0.85), 3 months (F=0.001, df=1, 346, p=0.96), or 1 year (F=0.01, df=1, 215, p=0.93). Further, there was no significant interaction between baseline negative symptoms and treatment group assignment in predicting change in negative symptoms at 6 weeks (F=1.34, df=1, 364, p=0.25), 3 months (F=0.03, df=1, 347, p=0.86), or 1 year (F=0.51, df=1, 216, p=0.48).

There was no significant interaction between the presence of the deficit syndrome and treatment group assignment in predicting change in positive symptoms at 6 weeks (F=1.41, df=1, 364, p=0.23), 3 months (F=0.65, df=1, 346, p=0.42), or 1 year (F=0.69, df=1, 215, p=0.41). There was also no significant interaction in predicting change in negative symptoms between the presence of the deficit syndrome and treatment group assignment at 6 weeks (F=0.61, df=1, 364, p=0.43), 3 months (F=0.48, df=1, 346, p=0.49), or 1 year (F=1.02, df=1, 215, p=0.31).

DISCUSSION

Using a relatively large group of over 400 patients hospitalized with refractory schizophrenia, we confirmed the greater effectiveness of clozapine, compared to conventional antipsychotic medications, in the treatment of positive symptoms and, less consistently, in negative symptoms. The magnitude of the differences observed here are smaller than those observed in some studies

(1,

6) but larger than those observed in others

(25). We have previously reviewed data suggesting that these differences reflect the possibility that the beneficial effects of clozapine may be lower among less acutely symptomatic patients and greater among those with higher levels of acute symptoms

(9,

26). Patients in this study had lower levels of acute symptoms than patients in studies that showed greater effectiveness

(1,

6) and higher symptom levels than patients in studies that showed less effectiveness

(25).

This report focused on a series of analyses designed to determine whether clozapine has a specific effect on negative as contrasted with positive symptoms or a specific benefit for patients with especially high levels of negative symptoms or patients manifesting the putatively poor-prognosis deficit syndrome. We found no evidence of specific effectiveness of clozapine in the treatment of negative as contrasted with positive symptoms. In fact, clozapine was significantly more effective than haloperidol at 6 weeks and 1 year for positive symptoms but not for negative symptoms, although at 3 months it was significantly more effective for both types of symptoms. Thus, although we replicated findings of previous studies showing that clozapine is superior to conventional medications in the treatment of schizophrenia, we found no evidence that its effect on negative symptoms was greater in magnitude than its effect on positive symptoms or that its effect on negative symptoms was independent of its effect on positive symptoms. These analyses suggest that clozapine’s effect on positive and negative symptoms is a single, undifferentiated effect.

Shifting from an analysis of contrasting symptom clusters to an analysis of contrasting patient subgroups, we also found no evidence of any specific effectiveness of clozapine in patients with more severe negative symptoms or in patients manifesting the deficit syndrome, a constellation of clinical phenomena thought to be associated with an especially poor prognosis.

Since one cannot prove the null hypothesis, these analyses cannot be taken as proof that clozapine does not have a discrete pharmacologic impact on negative as contrasted with positive symptoms. The data presented do suggest, however, that if clozapine does have a specific impact on negative symptoms, it is coincident with its effect on positive symptoms.

Several advantages, as well as limitations, of this study deserve note. The major advantages are the relatively large study group size, the availability of an appropriate comparison group, and the use of rigorous statistical methods to test for specific, independent clozapine effects on negative symptoms and syndromes. Previous studies addressed the single question, Is clozapine treatment associated with improvement in negative symptoms, even when positive symptoms are at a low level?

(8). However, we addressed two more complex questions: 1) Is the improvement in negative symptoms associated with clozapine treatment as compared to a control group greater than, or independent of, the improvement in positive symptoms associated with clozapine as compared to a control group? and 2) Compared to the control group, is the improvement observed with clozapine in patients with high levels of negative symptoms or with the deficit syndrome greater than the improvement observed with clozapine in patients with low levels of negative symptoms or without the deficit syndrome? The first question requires use of multiple regression methods that have been applied in previous studies. The second question requires use of an interaction analysis that has not previously been undertaken. The differences between our findings and those of previous studies may be due to the methodological strengths of the present study.

Several limitations of this study also deserve comment. First, it should be acknowledged that the groups compared at 1 year were not constituted entirely by random assignment. Patients in the clozapine group were those who continued to take clozapine for a full year and thus were likely to be among those who were most responsive to treatment. Even if patients in the haloperidol group discontinued the experimental treatment (often because of lack of response), they were retained in this study and treated with other conventional medications. However, the groups appear to be equivalent because there were no significant differences between them on any baseline measures. In addition, the 1-year findings are consistent with the 6-week and 3-month findings in the as-randomized sample.

A second limitation concerns our operational definition of the deficit syndrome. Since we did not have data on the duration of observed psychological state, we were forced to rely on cross-sectional assessments to identify patients with this syndrome. It is thus possible that the patients identified as having the deficit syndrome in this study were incorrectly identified because their flat affect, anergy, lack of motivation, and asociality were relatively recent in onset. We think that this is unlikely, since all patients in the study met entry criteria for medication refractoriness and had been sick with schizophrenia for over 20 years, on average. The subgroups with manifestations of the deficit syndrome and low levels of positive symptoms probably come closest to the clinical conceptualization of the deficit syndrome.

Finally, one might be concerned that our statistical analyses were not adjusted for the possibility that significant findings might appear by chance across multiple comparisons. Such adjustment was not necessary in this study, since none of the interaction analyses was statistically significant. Adjustment would be needed only to rule out the chance occurrence of spurious statistically significant findings had they emerged.

CONCLUSIONS

Clozapine does not appear to have a distinct benefit for negative as compared to positive symptoms in patients with refractory schizophrenia or to have differential beneficial effects in patients with high levels of negative symptoms or in patients with manifestations of the deficit syndrome. The greater effectiveness of clozapine, compared to conventional medications, in refractory schizophrenia is not specific to either clinical symptoms or subtypes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Members of the Cooperative Study Group on Clozapine are Denise Evans, M.D., Augusta, Ga.; Lawrence Herz, M.D., Bedford, Mass.; George Jurjus, M.D., Brecksville, Ohio; Sidney Chang, M.D., Brockton, Mass.; John Grabowski, M.D., Detroit; Lawrence Dunn, M.D., Durham, N.C.; John Crayton, M.D., Hines, Ill.; William B. Lawson, M.D., Ph.D., Little Rock; Yeon Choe, M.D., Lyons, N.J.; Richard Douyon, M.D., Miami; Edward Allen, M.D., Montrose, N.Y.; John Lauriello, M.D., Palo Alto, Calif.; Michael Peszke, M.D., Perry Point, Md.; Jeffrey L. Peters, M.D., Pittsburgh; Janet Tekell, M.D., San Antonio, Tex.; and Joseph Erdos, M.D., Ph.D., West Haven, Conn.