It is well established that both antidepressant agents and cognitive behavior therapy are effective in the treatment of major affective disorder

(1–

5). In this respect, several meta-analyses have indicated that cognitive therapy is the most effective form of psychotherapy for the treatment of major depression

(6,

7) and that it is claimed to be as efficacious as pharmacotherapy. In addition, several investigators reported that the combination of pharmacotherapy and cognitive behavior therapy was superior to either treatment alone

(8,

9). Others, however, found that the combination of treatments was no better than either treatment applied individually

(10,

11). It is of interest that under conditions in which cognitive behavior therapy and pharmacotherapy were not more effective than pharmacotherapy alone, the dropout rate was reduced by the combined treatment

(12,

13). In addition, relapse was somewhat reduced for patients who received cognitive behavior therapy, a combination of cognitive behavior therapy and pharmacotherapy, or cognitive behavior therapy following successful pharmacotherapy

(5,

14,

15).

Commensurate with the response to individual cognitive therapy, group cognitive therapy may be a viable therapeutic intervention for major depressive disorder

(16–

19). However, it was reported that group cognitive behavior therapy was as effective as individual therapy only during the early phases of treatment, after which the latter was more effective

(20,

21). Furthermore, while group cognitive behavior therapy effectively attenuated depression, the effectiveness of this treatment was not enhanced by imipramine treatment

(17,

22).

In contrast to the large number of studies that have assessed the effects of psychological or behavioral therapies in major depressive disorder, few studies have systematically evaluated the effectiveness of such treatment in dysthymia. Nevertheless, it has been suggested that such forms of therapy may be effective in the treatment of this illness

(5,

23,

24). Of course, it remains to be established whether group and individual cognitive behavior therapy are differentially effective in the treatment of this illness. Inasmuch as dysthymia is characterized by low self-esteem and impaired social and interpersonal functioning, cognitive behavior therapy may be particularly useful for the development of more adaptive behavior

(23) and for the improvement of negative self-perception. It was further suggested that cognitive behavior therapy may be useful in symptom control and prevention of relapse, particularly when the effects of pharmacotherapy are limited.

The number of studies examining the efficacy of antidepressants in dysthymic patients is limited; however, it is now generally accepted that a significant portion of dysthymic patients respond to pharmacotherapy. This evidence has been derived from clinical trials with tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), and, more recently, the newer serotonergic agents

(25). The specific serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have been shown to be as effective as the older tricyclics and better tolerated in the treatment of dysthymia

(26). It appears that the beneficial effects of the antidepressant agents may be particularly pronounced in certain subgroups of dysthymic patients, notably the subaffective type described by Akiskal

(27). In the main, the effects of these agents have been evaluated in open-label trials, although there have been reports showing positive antidepressant effects in double-blind, placebo-controlled trials

(25,

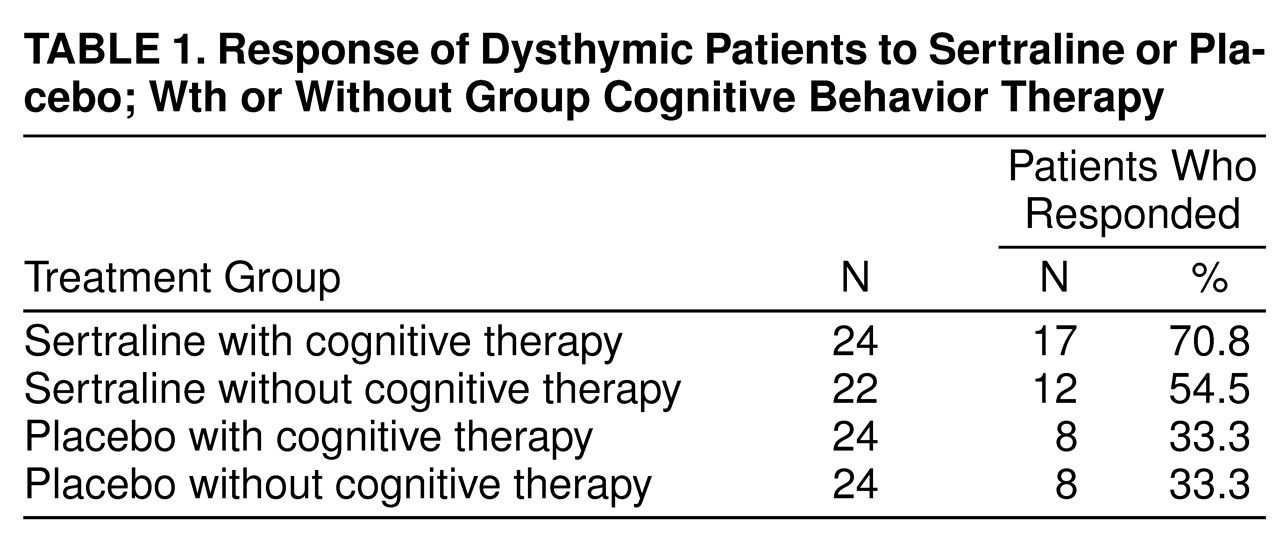

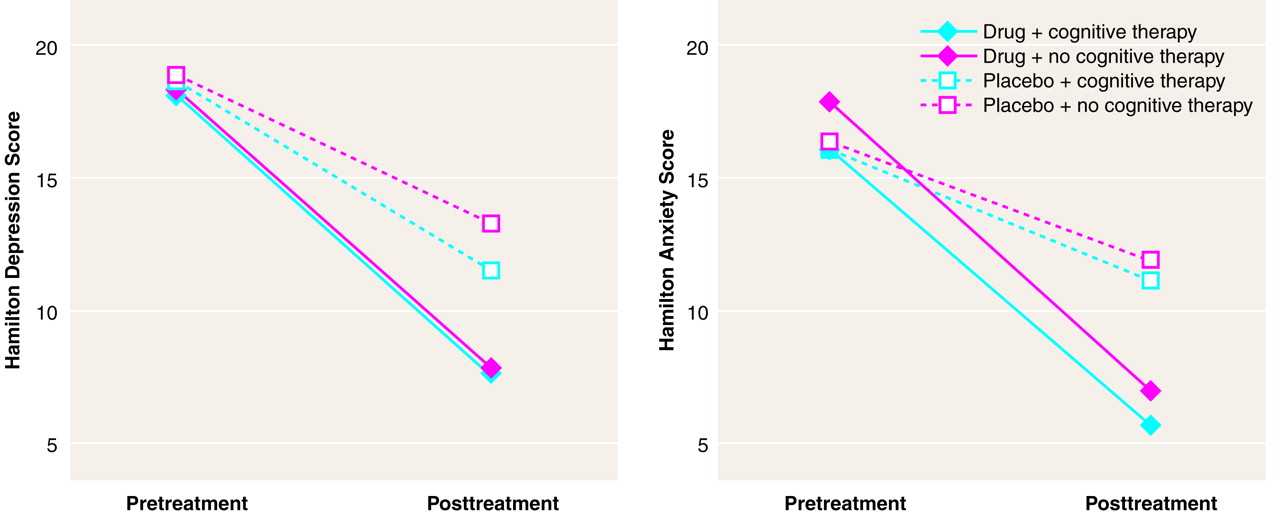

26). In the present investigation it was hypothesized that 1) an SSRI, sertraline, would be effective in the treatment of dysthymia in a double-blind, placebo-controlled design; 2) group cognitive behavior therapy would be effective in the treatment of dysthymia; and 3) the effects of the drug treatment would be augmented by group cognitive therapy. Inasmuch as symptom improvement may not necessarily parallel functional improvement, particularly with respect to different forms of treatment, the present investigation assessed the impact of the treatments not only on symptom improvement (as measured by standardized instruments such as the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety), but also on measures of quality of life, alterations of stress perception, and coping styles employed.

DISCUSSION

Several reports have confirmed that like the tricyclics

(42–

46) and MAOIs

(45,

47,

48), the newer antidepressants, including SSRIs such as fluoxetine and sertraline

(25,

41,

43,

49–

51), the reversible MAOI moclobemide

(46,

52–

56), and other agents such as the serotonin (5-HT

2) antagonist ritanserin

(57,

58), is efficacious in the treatment of dysthymia. The present investigation confirmed that relative to placebo, 12 weeks of treatment with sertraline in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial effectively reduced the clinical symptoms of dysthymia as measured by several standard instruments. This finding is in keeping with previous reports concerning the efficacy of sertraline for dysthymic patients

(25,

59). In the present study sertraline was also well tolerated, and adverse events were infrequent and only of mild or moderate intensity. Indeed, no dropouts occurred as a result of adverse events. The low rate of attrition was somewhat unusual but may stem from the nature of the subject recruitment and the exclusion of subjects with comorbid conditions, including personality disorders.

In contrast to the effects of the sertraline treatment, results for the group cognitive behavior therapy intervention were not as clear. Cognitive behavior therapy alone was not significantly more effective than placebo in reducing the clinical symptoms of dysthymia. Similarly, group cognitive behavior therapy did not significantly enhance the effectiveness of the pharmacotherapy. Although cognitive behavior therapy produced some enhancement of sertraline treatment, this effect was not significantly superior to the antidepressant alone; however, the number of subjects tested did not provide sufficient power to detect an enhancement of the drug effect. This should not be misconstrued to suggest that cognitive therapy is invariably without effect in dysthymia. As indicated by Hollon and DeRubeis

(60), cognitive therapy administered in conjunction with placebo treatment is not representative of the effects of cognitive therapy alone, and the placebo treatment may actually have attenuated some of the effects that might ordinarily be engendered by the cognitive behavior therapy intervention. Furthermore, it is possible that individual cognitive therapy may have yielded a better outcome than did cognitive therapy administered to groups. Moreover, the cognitive behavior therapy intervention in the present investigation was only of 12-week duration, and a more protracted course of treatment may have been required

(61), particularly for a long-standing illness such as dysthymia. It is also possible that cognitive behavior therapy adapted specifically for dysthymic patients may have a greater impact than that observed in the present investigation. There is as yet no empirically validated form of cognitive behavior therapy developed specifically for dysthymic patients. It is conceivable, however, that developments in cognitive behavior therapy since the commencement of this study may prove to be more appropriate for this population

(62,

63). It remains to be determined whether cognitive therapy, particularly for the drug-treated subjects, would be efficacious in preventing recurrence of dysthymia. In this respect, cognitive therapy may be more advantageous when applied during the maintenance phase of treatment (i.e., on completion of 12 weeks of pharmacotherapy, rather than being applied concurrently during the acute phase of treatment)

(64–

66).

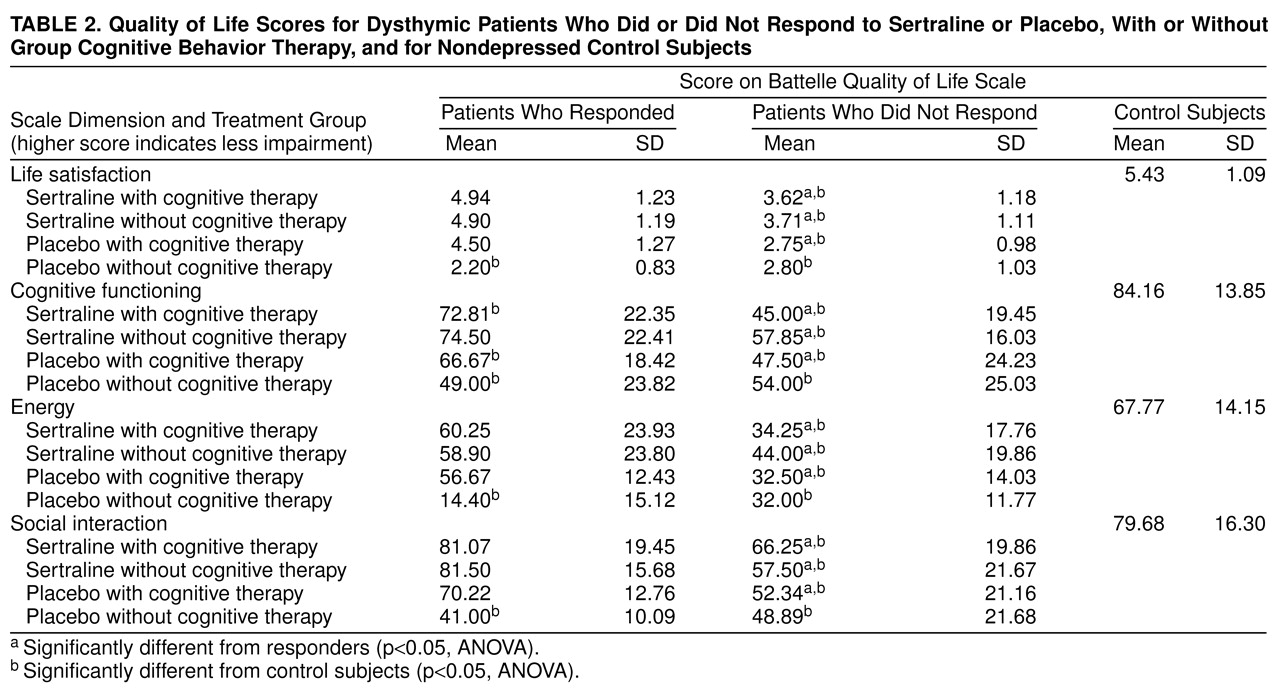

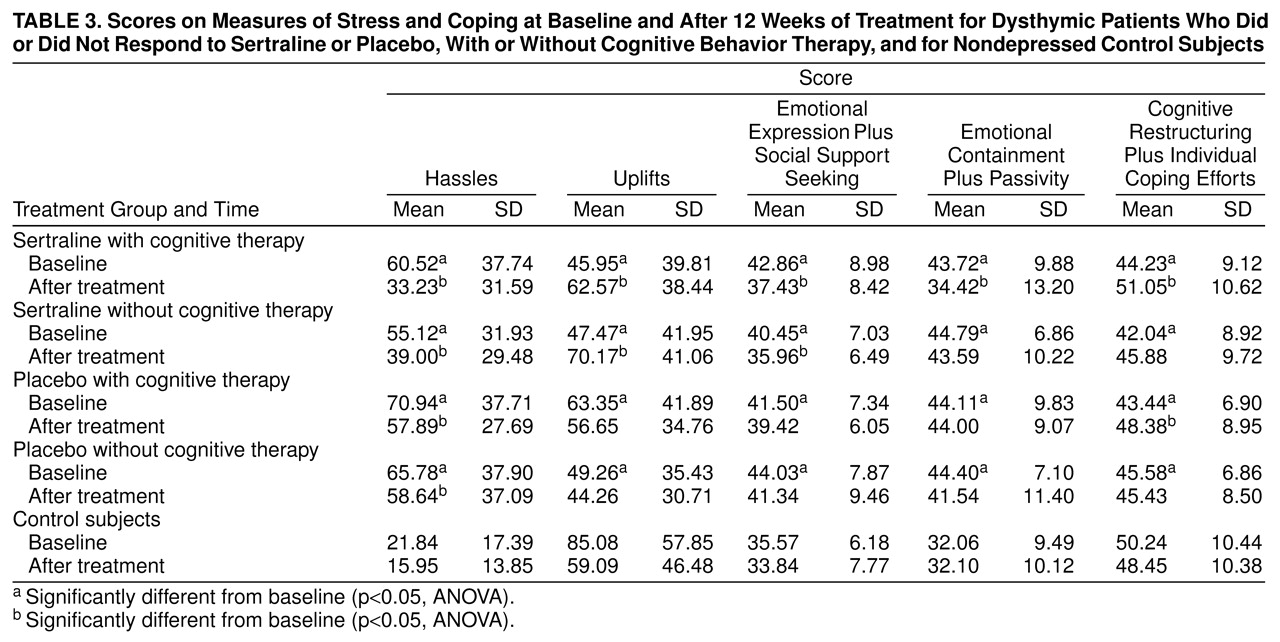

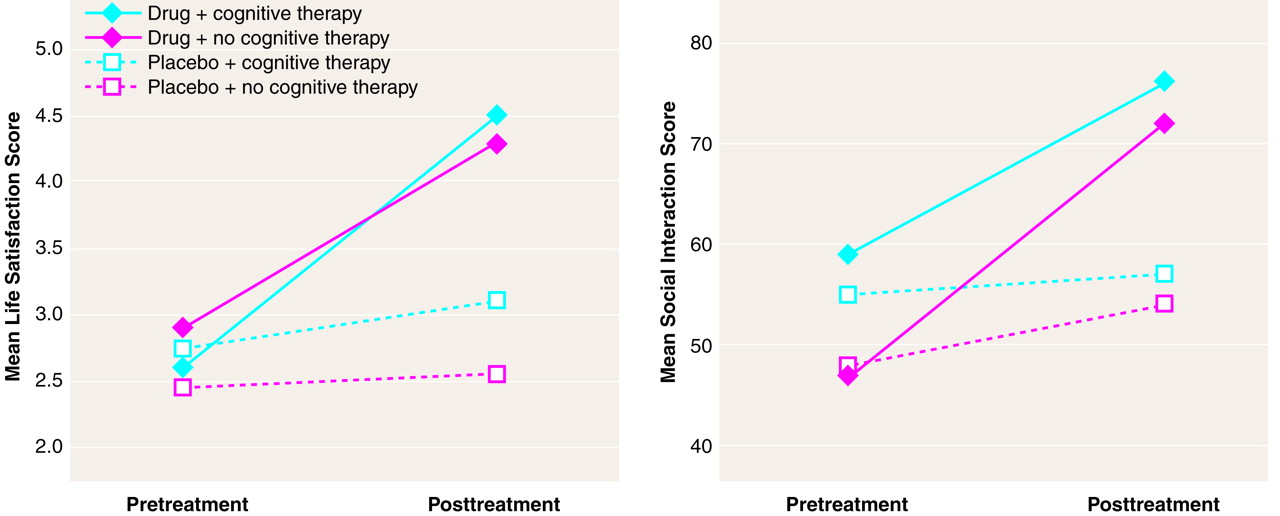

In addition to modifying the clinical symptoms of dysthymia, pharmacotherapy appeared to effectively reduce residual characteristics associated with the illness. For instance, perceived stress in the form of hassles was reduced, whereas uplifts were increased. Moreover, several of the maladaptive emotion-focused coping strategies, most notably emotional containment, were attenuated with pharmacotherapy. Although cognitive behavior therapy had no effect on clinical symptoms, it improved individual coping and cognitive restructuring, just as pharmacotherapy did, and the two treatments had additive consequences. Emotional containment plus passivity was affected only in patients who received both treatments concurrently. Thus, it would appear that sertraline treatment not only influences the primary clinical characteristics of dysthymia, but also markedly influences the secondary behavioral concomitants of the illness. Moreover, the effects of the drug on coping processes may be augmented by group cognitive therapy.

It has been reported that the quality of life is substantially reduced in depressive disorders

(67,

68). Similarly, social and occupational impairments are common in dysthymic patients

(42,

69), and antidepressant treatment has been shown to attenuate the social impairments

(42). It was similarly observed in the present investigation that dysthymia was accompanied by marked disturbances in various dimensions of the quality of life, including health perception, energy/vitality, cognitive functioning, alertness, social functioning, and life satisfaction. Treatment with sertraline largely attenuated these impairments, just as this treatment reduced perceived stress and enhanced perceived uplifts. Although group cognitive behavior therapy did not have an overall effect on the quality of life, it is interesting that among those patients who responded favorably to this intervention, the enhancement of quality of life scores was as marked as that in drug responders. In contrast, among placebo responders there was no enhancement in quality of life measures. In effect, while placebo responders and those patients who responded favorably to cognitive behavior therapy exhibited similar profiles of symptom alleviation, these two groups could readily be distinguished from one another on the basis of secondary or residual symptoms. Thus, although a positive treatment response was less frequent following group cognitive behavior therapy than after pharmacotherapy, in a subset of patients the cognitive behavior therapy intervention had definite benefits in terms of functional improvement.

It seems that the group intervention used in the present investigation, although subtle in its effects on clinical characteristics, provoked functional changes beyond those seen in placebo responders. It has been proposed that the high rate of recurrence of major depressive disorder may stem from undertreatment of the illness, as reflected by the persistence of residual symptoms

(23,

70–

73). In a like fashion, it is possible that those treatments which permit residual dysthymic features to persist (e.g., inadequate antidepressant dose or duration of treatment) may also be least effective in preventing recurrence of this illness. It is certainly conceivable that by virtue of its effects on the secondary features of dysthymia, cognitive behavior therapy may act to limit illness recurrence. As indicated earlier, forms of cognitive behavior therapy that incorporate recent advances in this approach and are tailored toward the whole spectrum of specific symptoms of dysthymia may also prove to be more efficacious in this respect

(74,

75). Finally, given that changes in the quality of life distinguished between patients who responded to cognitive therapy and to placebo, the possibility ought to be considered that this functional measure may also be useful in distinguishing genuine drug responders from drug-treated patients actually exhibiting a placebo response. Such a differentiation may prove to be a valuable tool in predicting relapse and may be useful in evaluating the efficacy of treatment.