Anxiety sensitivity is the fear of anxiety-related sensations. It is thought to arise from beliefs that these sensations have harmful consequences (

1–

4). For example, an individual may fear that the sensation of palpitations indicates a serious, life-threatening condition, such as a heart attack. According to expectancy theory, such an individual may become anxious whenever this symptom is experienced and may tend to avoid activities or places that are believed to bring it on. Anxiety sensitivity theory proposes that some individuals are more prone than others to respond to anxiety symptoms in this fashion. In other words, the higher an individual’s level of anxiety sensitivity, the more that individual is likely to experience anxiety symptoms as alarming, dangerous, and threatening.

There is considerable empirical support for the role of anxiety sensitivity in panic disorder (for reviews see references

4 and

5). Anxiety sensitivity, as assessed by the Anxiety Sensitivity Index (

6), is higher in people with panic disorder than in healthy comparison subjects and in patients with another anxiety disorder, social phobia (

7,

8). In normal volunteers, anxiety sensitivity predicts anxious responding to a variety of panic-provoking paradigms such as hyperventilation and CO

2 inhalation (

9–1

1). However, anxiety sensitivity does not seem to predict consistently response to all agents that induce panic, cholecystokinin tetrapeptide being a case in point (

12; see reference

13 for review).

Anxiety sensitivity has also been found to be a risk factor for the development of panic disorder. In a prospective study of young adults under stress (i.e., military basic trainees), anxiety sensitivity was found to predict the onset of panic attacks (as well as generalized anxiety and depressive symptoms) over a 5-week period (

14). The latter finding, which has since been replicated (cited in reference

15), confirms that high anxiety sensitivity at one time point is associated with the development of panic disorder (and perhaps other anxiety or depressive disorders) at a later time point.

Panic disorder runs in families (

16–

20). Moreover, twin studies clearly demonstrate that the disorder is heritable (

21–

24). The latter finding has generally been interpreted to mean that patients with panic disorder inherit a physiologic or biological risk factor for panic. Enhanced sensitivity to 35% CO

2 among family members of patients with panic disorder has emerged as a promising candidate in this regard (

25,

26). Surprisingly, though, little attention has been paid to the possibility that the transmission of a psychological construct such as anxiety sensitivity might explain the heritable nature of panic disorder. This is despite the fact that Reiss and McNally originally posited that genetic factors might influence anxiety sensitivity (

3) and despite a growing awareness that other complex attitudes and behaviors can have a heritable basis. The purpose of the present study was to 1) estimate the magnitude of genetic and environmental influences on anxiety sensitivity, and 2) determine whether the magnitude of any genetic influence on anxiety sensitivity changes when only cases of extreme anxiety sensitivity (such as would be seen in panic disorder) are examined. Since most authorities agree that anxiety sensitivity is multifactorial (

27,

28), we examined the heritability of anxiety sensitivity as a unifactorial and multifactorial construct.

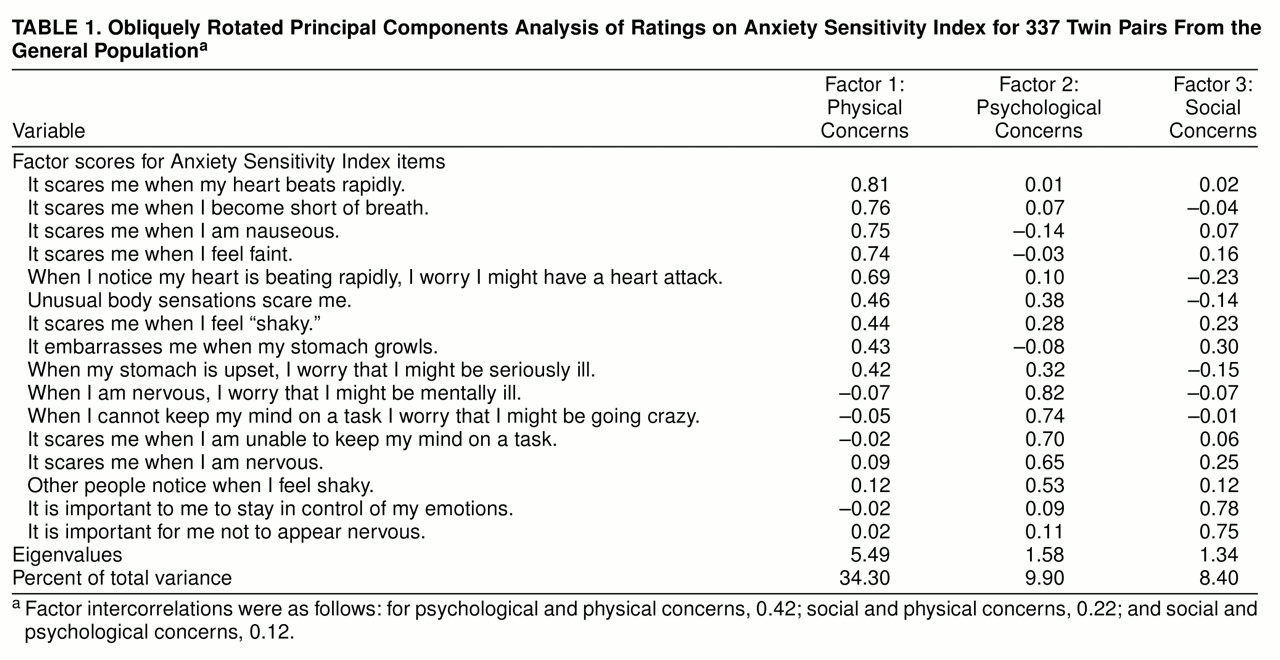

RESULTS

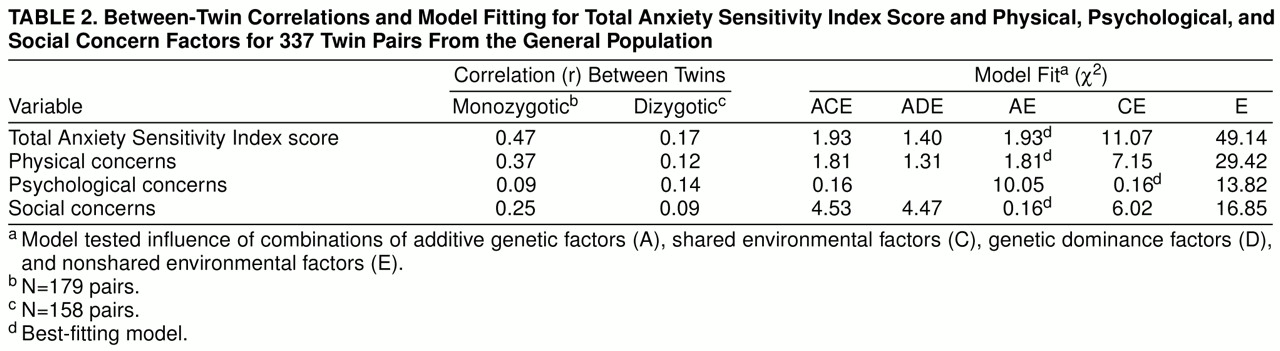

Twin correlations and model-fitting statistics are presented in

table 2. A model specifying additive genetic and nonshared environmental effects (AE model) provided the most satisfactory fit to the total Anxiety Sensitivity Index score and the physical and social concern factors. A model specifying shared and nonshared environmental effects (CE model) could account for all of the variance of psychological concerns.

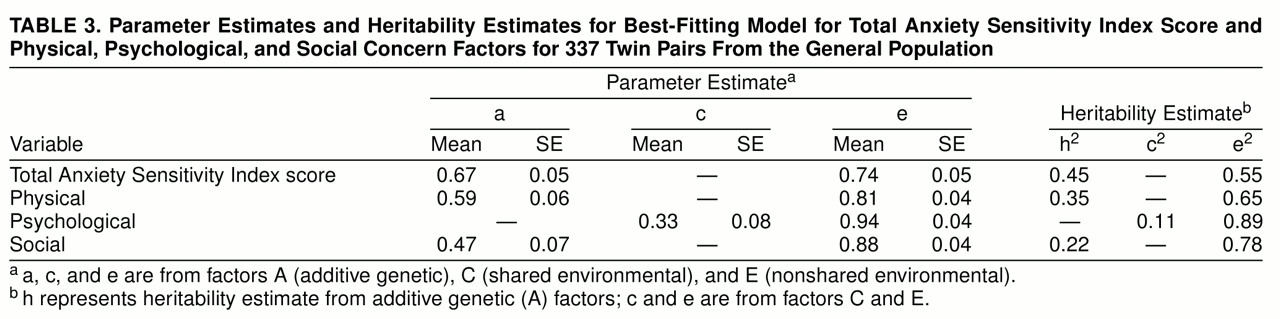

Table 3 presents the parameter estimates, standard errors, and the heritability estimates. Additive genetic factors accounted for 45%, 35%, and 22% of the total variance on the total Anxiety Sensitivity Index score, physical concerns scores, and social concerns scores, respectively. Shared environmental influences accounted for 11% of the total variance on psychological concerns. Nonshared environmental influences (and error) accounted for the greatest proportion of the variance on all scales (range=55% to 89%).

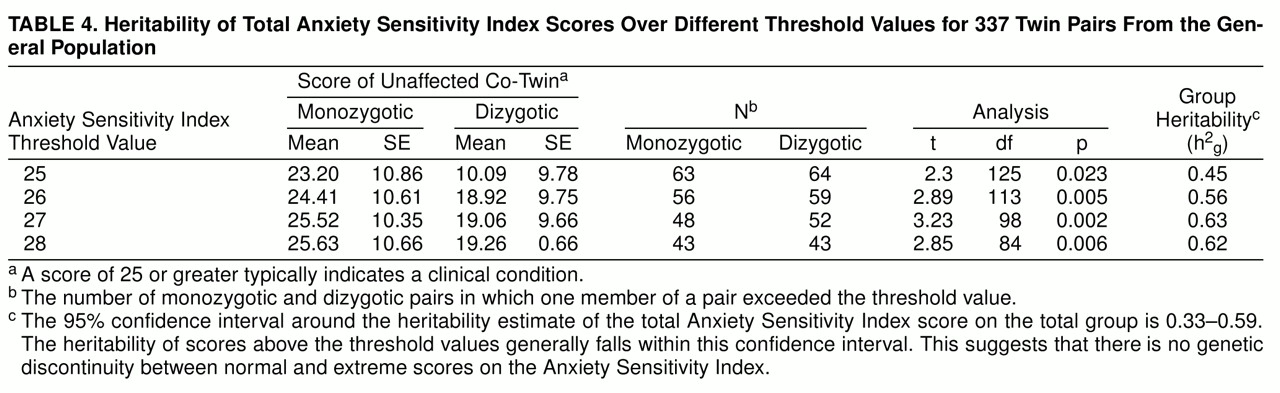

Table 4 provides the results of the DF analysis. Group heritability, or the heritable basis of the total Anxiety Sensitivity Index scores above the threshold of 25 to 28, ranged from 45% to 63%. The 95% confidence interval around the heritability estimate of the total Anxiety Sensitivity Index score for the total group is 0.33–0.59. The group heritability estimates generally fall within this confidence interval, suggesting that there is no genetic discontinuity between normal and extreme scores on the Anxiety Sensitivity Index.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the heritability of anxiety sensitivity. We found that anxiety sensitivity has a strong heritable component, accounting for nearly half of the variance in total anxiety sensitivity scores. Results of the DF analysis showed that the magnitude of genetic effects across the whole range versus extreme range Anxiety Sensitivity Index scores fell within the same general parameters. These results support the idea that high scores on the Anxiety Sensitivity Index (characteristic of panic disorder) and scores in the subclinical range share the same common genetic factors. We use the word “support” because it is possible that qualitatively different genetic factors influence extreme and normal range scores to the same degree.

Whereas it has generally been hypothesized that the heritable nature of panic disorder reflects the genetic transmission of a physiologic risk factor (e.g., hypersensitivity to CO

2) (

25,

26), this may be too narrow a formulation. In view of our findings, serious consideration should be given to the possibility that an attitudinal or cognitive risk factor (i.e., anxiety sensitivity) is being genetically transmitted. This should not be seen as an unexpected or novel hypothesis (

3). As noted by Kendler (

42), considerable evidence now points to the heritability of many complex psychological traits that may themselves serve as risk factors for psychiatric disorders. Certainly, personality traits have a large heritable component (

43); hence, it is not surprising that anxiety sensitivity is also heritable. Thus, our findings raise the question of whether anxiety sensitivity is inherited independently from “neuroticism,” a question that we hope to address in future studies. Given the empirical support for heritability of a nonspecific neurotic factor in the anxiety disorders (

44,

45), this must be seriously considered.

Our study has several limitations. Among these are a limited group size and few male twin pairs. Our interpretation of the data is also limited by the relatively restricted range of anxiety sensitivity scores encountered in this group of twins from the general population. We demonstrated that the upper range of anxiety sensitivity scores in our study group (i.e., high 20s) is not inherited differently from lower anxiety sensitivity scores; however, we cannot extrapolate with certainty to state that this will necessarily apply to the much higher anxiety sensitivity scores (i.e., 30 and above) seen in some patients with panic disorder. Thus, although we believe that our findings have relevance to the understanding of the heritability of disorders characterized by pathological levels of anxiety sensitivity (i.e., panic and perhaps other anxiety and depressive disorders) (

4), this will require further study.

With these limitations in mind, our findings lead us to tentatively conclude that perhaps what is inherited in panic disorder is a tendency to view anxiety symptoms as frightening. It is expected that anxiety sensitivity, like other cognitive tendencies, will eventually be localized within specific neural networks (

46). In order to make further advances in this regard, we would propose that future studies evaluate anxiety sensitivity and other risk factors within this broader context. For example, heritability studies of panic at the level of “disorder” might simultaneously examine anxiety sensitivity heritability at the level of “trait”; and functional neuroimaging studies of anxiety disorders might use neuropsychologically relevant tasks to activate neural structures (e.g., components of the limbic system) that could underlie anxiety sensitivity (

47).

When the heritability of the three factors of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index are examined separately, there is some evidence for differential contributions of additive genetic and environmental influences. This must be considered a very tentative finding, given that there are differences among the factors in the number of items with salient loadings (i.e., the psychological and social concerns factors might be less reliable), which may lead to spurious findings in this regard. We found that shared environmental influences accounted for a substantial proportion (11%) of variance in the psychological concerns factor, suggesting that important aspects of this component are influenced by family environment. If this finding is confirmed, then the implication is that interventions directed toward the family milieu might lessen the development of anxiety sensitivity and, hence, might prevent the onset of some forms of psychopathology. Other investigators have similarly hypothesized that specific genetic factors or specific social learning experiences might influence specific factors of anxiety sensitivity (

48), leading us to believe that this is an area ripe for further study.

Total Anxiety Sensitivity Index scores and scores on two of the three factors, most notably the physical concerns factor, were best modeled by using a combination of additive genetic and unique environmental influences. Environmental factors account for a large proportion of the variance in Anxiety Sensitivity Index scores, leading us to speculate about the nature of the experiences that may increase anxiety sensitivity and, hence, the risk for panic disorder. The literature suggests that several types of events deserve consideration in this regard. Childhood sexual or physical abuse, a known risk factor for the development of panic disorder (

49), could produce feelings of loss of bodily autonomy and concerns related to physiologic hyperarousal. Suffocation experiences (

50) and other adverse respiratory experiences in childhood, such as asthma (

51,

52), might sensitize an individual to fear sensations associated with breathlessness. Learning to “catastrophize” about the occurrence of bodily symptoms in general might also lead to higher than normal levels of anxiety sensitivity (

53). Thus, although our findings highlight the heritable nature of anxiety sensitivity, they also point to the need to identify experiential factors that influence anxiety sensitivity and to investigate how these factors interact with genetic factors to trigger panic attacks.