The ability to distinguish schizophrenia from depression is perhaps most difficult early in the course of a schizophrenic illness. The prodrome of schizophrenia may resemble depression, and many symptoms used in the DSM-III-R and DSM-IV algorithms for a major depressive episode (e.g., anhedonia, concentration difficulties, psychomotor abnormalities, sleep disturbance) are nonspecific, being extremely common in schizophrenia as well

(1). It is not surprising, therefore, that many patients who go on to develop schizophrenia “pass through” the diagnosis of a mood disorder early in their illnesses. This may also, in part, reflect a clinical bias, in the face of uncertainty, to diagnose depression in favor of schizophrenia because of the more favorable prognosis and response to treatment and the lesser stigmatization of affective illness

(2,

3).

This inherent overlap of symptoms between depression and schizophrenia renders attempts to assess the prevalence, specificity, and predictive validity of those symptoms tautological. The ability to test the sensitivity and/or specificity of any phenomenological measure is constrained by the accuracy with which true “caseness” can be determined. As there are no definitive pathophysiological tests for either schizophrenia or mood disorder, we must settle for other measures to validate the diagnoses. Among the types of validators proposed by Robins and Guze

(4), longitudinal course/outcome is arguably the most powerful and perhaps best proxy for true caseness in differentiating schizophrenia from mood disorders.

To determine, therefore, the prevalence of depressive symptoms in early schizophrenia, we analyzed subjects whose depressive symptoms had been objectively rated in the initial phase of the illness (often at a time when the diagnosis was unclear) and who went on to develop clear-cut schizophrenia as assessed at a prospective 5-year follow-up. We hypothesized that the DSM-III-R criteria A symptoms for a major depressive episode would be frequent early in the course of schizophrenia.

METHOD

The subjects were enrolled in a prospective longitudinal study of recent-onset psychosis, details of which have been described previously

(5). This study recruits patients hospitalized for the first time for a psychotic disorder within the previous 5 years. The exclusion criteria include serious neurological illness or a primary diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Follow-up of more than 5 years has now been achieved for 70 subjects who received DSM-III-R or DSM-IV diagnoses of schizophrenia based on semistructured face-to-face diagnostic interviews at both 2- and 5-year follow-up. Of these 70 subjects, 54 were male and 16 were female; their average age at intake was 24.63 years (SD=5.23), and their average age at onset of illness was 20.36 years (SD=4.22).

At intake, the subjects were assessed with the Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (CASH)

(6), which provides, among a wealth of other information, a detailed assessment of symptoms related to mood disorders. Each DSM-III-R criterion A symptom for a major depressive episode was rated on a 0–5 scale (0=not present, 1=questionable, 2=mild severity, 3=moderate, 4=severe, and 5=extreme). These symptoms include dysphoria, loss of interest or pleasure, altered appetite, insomnia or hypersomnia, psychomotor agitation or retardation, loss of energy, feelings of worthlessness and guilt, diminished concentration, and thoughts of death or suicide. The proportion of subjects experiencing each symptom with at least a moderate level of severity (rating of 3 or greater) at intake was calculated. To test whether each subject would have met the criteria for a depressive episode, we applied an algorithm based on DSM that requires the presence (rating of 3 or greater) of at least five of the nine symptoms, one of which had to be either dysphoric mood or loss of interest/pleasure.

Diagnostic conferences were held for each patient at index admission and at the 2- and 5-year follow-ups, with the primary purpose of establishing a consensus diagnosis. The clinical history was presented to a group of at least three research psychiatrists (including M.F., P.N., and N.C.A.) along with postdoctoral fellows, research nurses, and others. The patient was interviewed by one research psychiatrist, and time was left for questions from others for clarification. After the interview, each of the research psychiatrists independently filled out a form indicating his or her opinion of the diagnosis by DSM-III-R criteria, following which a discussion was held and a consensus diagnosis generated.

RESULTS

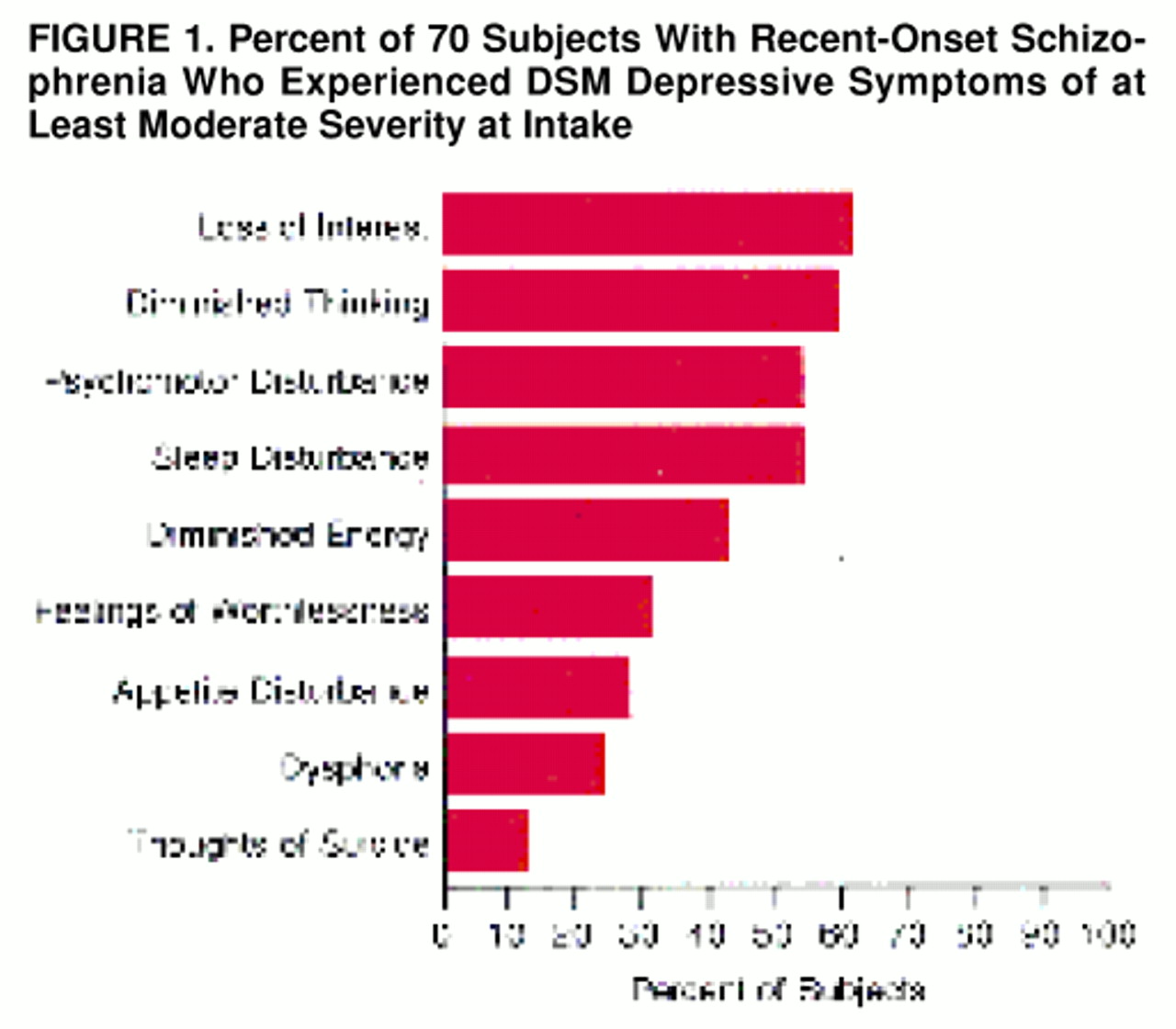

The rate of each depressive symptom at intake is shown graphically in figure 1. Four depressive symptoms were present to at least a moderate degree (rating of at least 3) in a majority of the subjects. These included loss of interest or pleasure (61.4%), concentration difficulties (60.0%), hypersomnia or insomnia (54.3%), and psychomotor agitation or retardation (54.3%). Diminished energy (42.9%), feelings of worthlessness (31.4%), dysphoric mood (24.3%), and appetite disturbance (28.6%) were also common. Twenty-four subjects (34.3%) met our algorithmic criteria for a major depressive episode at the time of intake.

DISCUSSION

In this 5-year prospective study of recent-onset schizophrenia, we found a high rate of depressive symptoms early in the course of illness. More than one-half of the depressive symptoms were present to a substantial degree in a majority of subjects, and even dysphoria, often used as a discriminator between the illnesses, was present in nearly 25% of the subjects. These data are consistent with findings from a number of other prospective studies that have examined this issue. Johnson

(7) found nearly one-half of subjects with new-onset schizophrenia to be depressed. House et al.

(8) identified depression in 22% (15 of 68) of first-episode subjects, and Koreen et al.

(9) found that 75% of first-episode subjects had depressive symptoms when a liberal definition of depression was used and 22% when a more stringent definition was used.

The data also highlight the apparent nonspecificity of the current diagnostic criteria for depression versus early schizophrenia. More than one-third of the subjects who went on to develop clear-cut schizophrenia satisfied the algorithmic criteria for a major depressive episode at the time of their admission to the study. In accord with this and with the potential diagnostic bias mentioned at the outset of this paper, many of the subjects in this study were diagnosed with and treated extensively for depression before the diagnosis of schizophrenia finally “declared itself.” Given the improved side effect profiles of newer antipsychotics and evidence suggesting a potentially detrimental effect of untreated psychosis

(10), we suggest that this bias toward diagnosing affective disorder in the face of uncertainty may need to be reconsidered.