The study of negative symptoms in schizophrenia is receiving renewed attention because of the possible effects of the new “atypical” antipsychotic drugs on what were once proposed to be refractory symptoms

(1). Although negative symptoms have since been shown to be influenced by both medication and exacerbation, it is clear that some patients have residual negative symptoms

(2, >

3) that have not responded satisfactorily to traditional pharmacological treatment and may not respond to the new serotonin/dopamine antagonists either

(4).

Recent attempts to incorporate the idea of secondary versus primary negative symptoms include categorization by longitudinal presentation (e.g., the deficit syndrome

[2] and Kraepelinian classifications

[5–

7]), as well as statistical adjustment for secondary sources

(8–

10). The focus of evaluations of the deficit syndrome has been to distinguish primary or enduring negative symptoms from those that are the result of medication, exacerbation, or the psychotic process

(11), while Kraepelinian classification focuses on continued inability (for at least 5 years) to function independently.

Additional studies have specifically addressed the hypothesis that negative symptoms remain stable over time. Despite differences in follow-up time and scale measurements, most studies support the idea that negative symptoms, while less variable than psychotic symptoms, do change over time (

12–

17). However, there is also some indication that there is less change in negative symptoms as the illness progresses

(15,

18).

Specific pharmacological intervention paradigms have shown direct treatment and withdrawal effects on negative symptoms

(24–

27). Our group

(28) has previously studied symptom profiles

(29) in drug-free patients without exacerbation of symptoms in an attempt to empirically identify primary negative symptoms by controlling for level of positive symptoms as well as medication effects. The assessment of negative symptoms in drug-free patients at the time of relapse, combined with a matching assessment when they are on medication, provides a unique opportunity for determining medication and exacerbation effects on negative symptoms. A study by Miller et al.

(8) used a paired assessment with a fixed 3-week drug washout and evaluated the secondary effects of extrapyramidal side effects, psychosis, disorganization, and depression. These investigators concluded that negative symptoms increased following drug withdrawal and that the change was also associated with changes in positive symptoms and symptoms of disorganization. However, in a competing model, there were no significant stand-alone predictors of the change in negative symptoms.

Since the effect of atypical antipsychotic agents on negative symptoms has been suggested to be their advantage over traditional antipsychotics, it is important to define the concept of negative symptoms more clearly with respect to which symptoms respond to treatment, how often they respond, and to what extent. The purpose of the present study was to use a double-blind drug withdrawal paradigm to determine whether meaningful factors that are similar when patients are both on and off medication are present and to evaluate possible secondary sources of negative symptoms.

METHOD

The study group consisted of 93 physically healthy male patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who were participating in a relapse prediction/drug withdrawal protocol. All subjects were screened with complete physical, neurological, and psychiatric evaluations conducted by board-certified psychiatrists. Trained staff obtained the diagnostic data from a structured interview in which the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Lifetime Version (SADS-L)

(30) or the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID)

(31) and a DSM‐III-R checklist were used. Patients who met the DSM‐III-R criteria for alcohol or substance abuse/dependence were excluded at the time of the study unless they had been in remission for at least 6 months. Diagnostic, clinical, and demographic data were examined at a consensus conference. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent for the protocol was obtained from each subject and reviewed by the institutional review board.

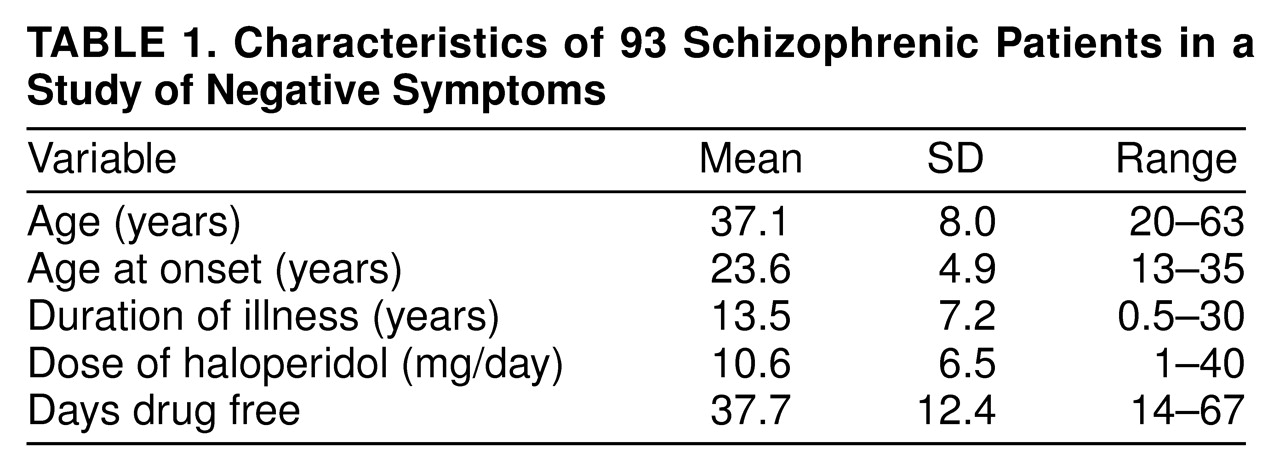

All subjects were put on a low-monoamine and caffeine- and alcohol-free diet at admission, and their medication was converted to haloperidol for at least 3 months if they were not already being treated with haloperidol. Benztropine was administered in doses of 1–4 mg/day if necessary during stabilization but was withdrawn at least 2 weeks before the preliminary evaluation; thus, no pharmacological control over extrapyramidal side effects was used that could affect the data presented. No other medications were given. Identical-looking placebo capsules replaced the haloperidol capsules overnight after baseline procedures were performed. The drug-free period was a maximum of 6 weeks before follow-up procedures. Patients who met criteria for relapse within 6 weeks of drug withdrawal (N=41) were given neurochemistry evaluations and behavioral ratings at that time; the remaining patients (N=52) were evaluated at the end of the 6-week period. Patients remained in the hospital for the duration of the study. Characteristics of the patients are shown in

table 1.

Negative symptoms were measured with the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS)

(32) on a weekly basis by therapists who were blind to medication status. Secondary sources of negative symptoms were evaluated with use of the Bunney-Hamburg global psychosis scale

(33), the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)

(34), and a modified version of the Simpson-Angus Rating Scale

(35) for extrapyramidal side effects that contained eight of the original 10 items, excluding leg pendulousness and head dropping, which are commonly not rated. Extrapyramidal side effects were approximated by the mean of all eight scores on the Simpson-Angus scale; anxiety/depression was assessed as the mean of scores on the anxiety, depression, and guilt items from the BPRS. Relapse was defined as a 3-point increase in the Bunney-Hamburg global psychosis rating from the baseline psychosis rating established the last week the patients were taking haloperidol. The increase had to be sustained for 3 days before the relapse criterion was considered to have been met.

Principal components analysis (varimax rotation) was performed on the haloperidol-treatment and drug-free SANS items separately to determine whether there were meaningful factor scores that were consistent across medication conditions. Linear regression was then used to determine the relation between the negative symptom factors and possible secondary sources.

RESULTS

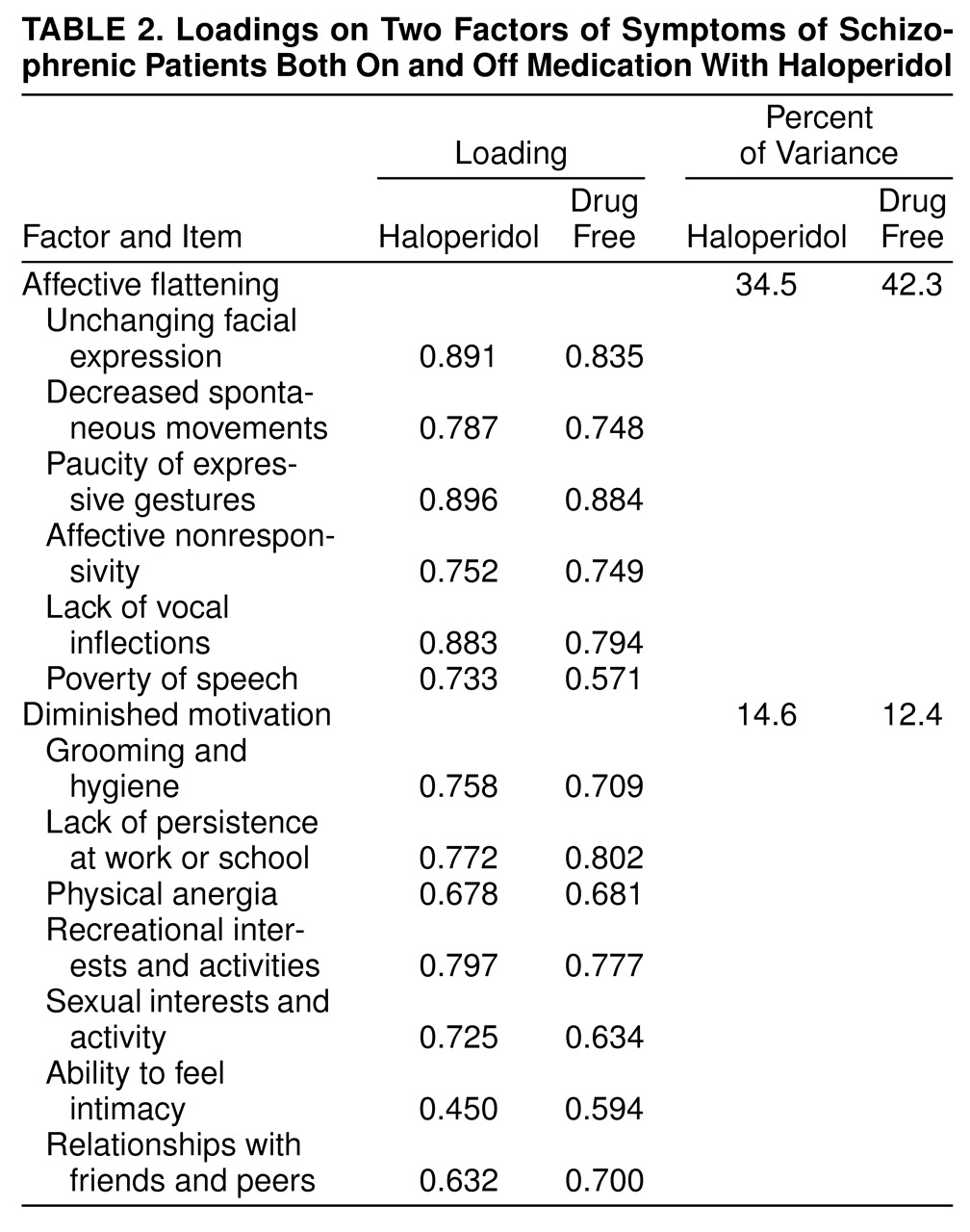

Of the 20 SANS items (eliminating global and subjective ratings), a factor including most of the items contained in the affective flattening subscale as well as poverty of speech accounted for 34.5% of the total variance when the patients were taking haloperidol and 42.3% of the variance when they were drug free (

table 2). The next highest factor included similar items when the patients were on and off medication, consisting of mostly anhedonia and apathy items; this similar factor was observed in a combination of medicated and unmedicated patients by Keefe et al.

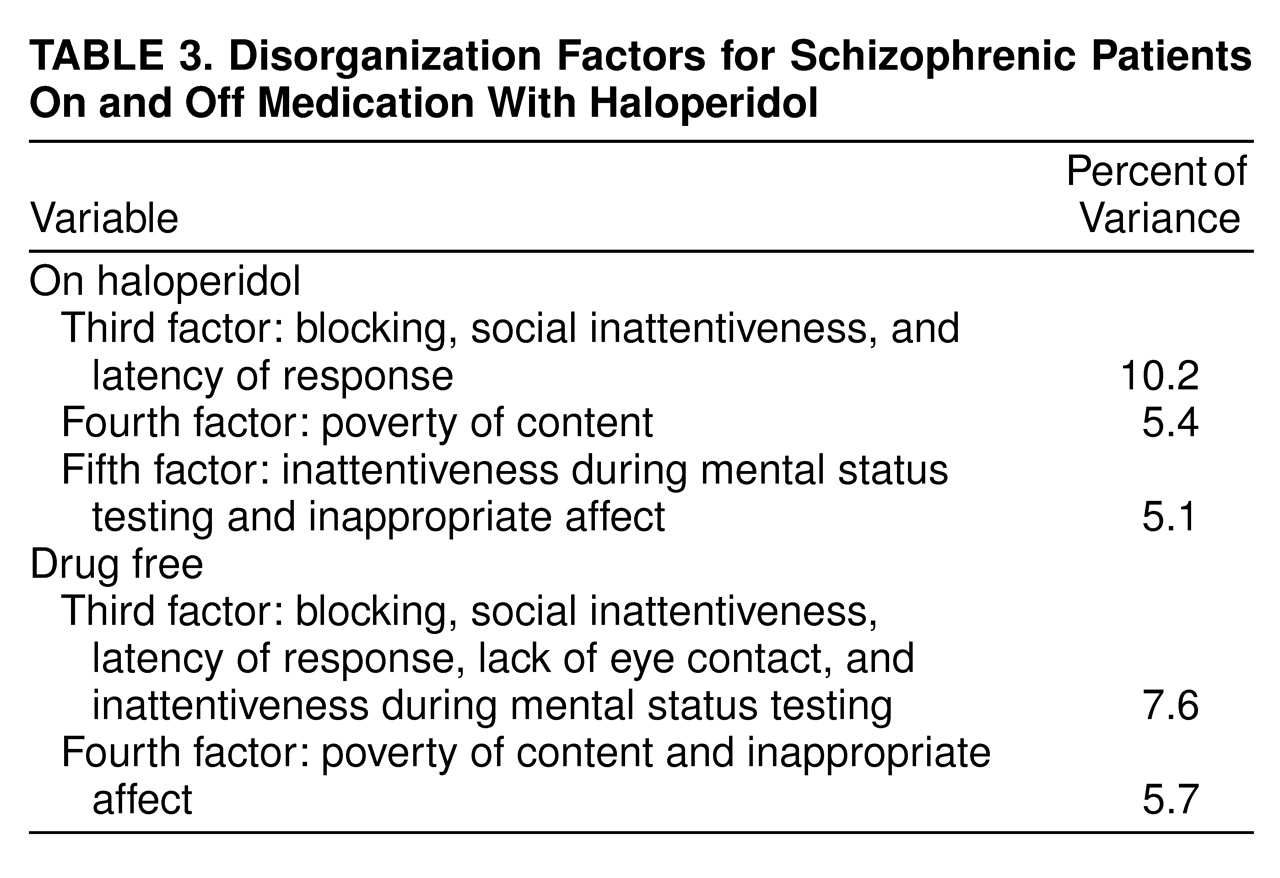

(6). The haloperidol condition and drug-free condition factor loadings were compared across all 20 variables for these two factors; the resulting Pearson correlation coefficients were 0.923 and 0.927 for the affective and anhedonia/apathy factors, respectively (in each case, df=18, p<0.0005). The remaining factors included what have been found to be disorganization/positive symptom items, which are considered to be dimensions independent of negative symptoms and thus were not pursued in further analysis (

table 3).

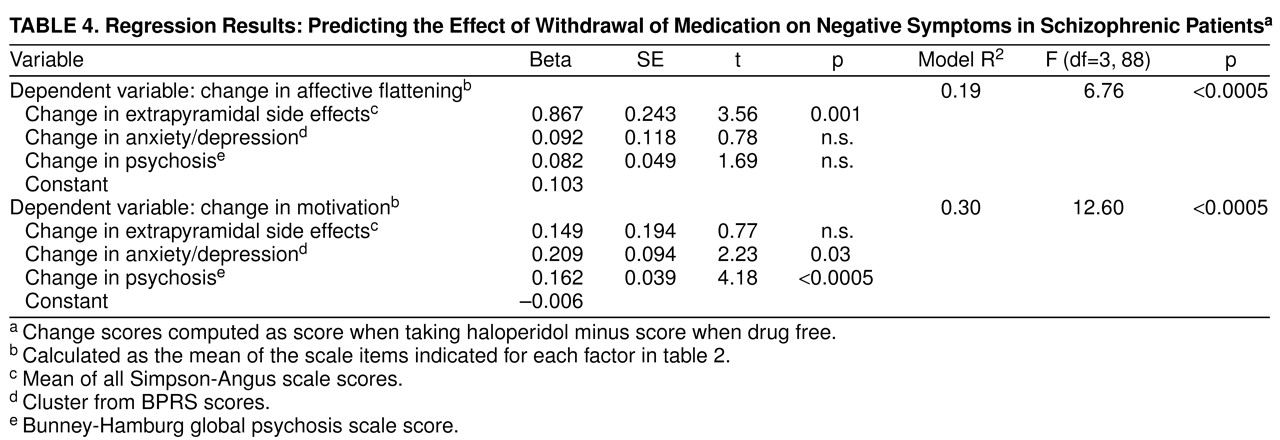

For use in further analysis, means of the individual items with high loadings (>0.50)—all items listed in

table 2—were used as approximate scores for the factors; these factors were termed affective flattening and diminished motivation. To test the “primary” nature of the factors, effects of withdrawal on secondary sources such as psychosis, extrapyramidal side effects, and anxiety/depression were tested for significant associations with the effect of withdrawal on negative symptoms (

table 4). While changes in motivation were correlated with changes in psychosis and anxiety/depression, the effect of withdrawal on affective flattening was associated only with change in extrapyramidal side effects.

DISCUSSION

This study used an evaluation of patients’ symptoms when they were on and off medication to discriminate primary from secondary negative symptoms associated with pharmacological treatment (i.e., drug-responsive, drug-induced)

(36) and those secondary to or intensified by psychotic exacerbation

(27,

37). The fact that factor structures of negative symptoms were similar with and without medication lends support for the idea that the relationships among the symptoms are independent of both medication and exacerbation. This result is unique to this study and particularly relevant for the further understanding of the primary/secondary distinction in the study of negative symptoms.

In schizophrenia research, use of factor analysis to determine clusters of symptoms is well documented. Most studies have attempted to verify the original positive/negative symptom dichotomy proposed by Crow

(1). Considerable evidence has shown that a third syndrome, loosely termed disorganization, exists separately from both the positive and negative dimensions

(38–

40). However, the factor analysis of negative symptoms along with positive symptoms will emphasize their similarities, relative to psychotic symptoms, and minimize their differences. This is true because principal components analysis and further extensions to factor analysis account only for the variance in the data at hand.

Factor analyses of negative symptoms only are more clearly able to aid in the distinction among patterns of negative symptoms that may be different in their etiology and course. Despite differences in study populations and severity of illness among study groups, the studies thus far, including the current one, have shown strikingly similar results in regard to underlying negative symptom factors

(6,

39,

41–

44). In particular, these studies also showed a wide variation in sample sizes (range=40–549). The factors emerging from these studies have consistently included ones that represent affective flattening and diminished motivation (anhedonia and apathy) and various numbers of factors representing disorganization (e.g., attentional impairment, alogia, poverty of content).

Further analysis indicated that the negative symptom factors are also differentiated by their secondary correlates. Specifically, diminished motivation was associated with exacerbation and mood effects, while affective flattening showed only medication effects. This would indicate that the motivation factor represents the aspect of negative symptoms that is responsive to traditional antipsychotic treatment; i.e., it parallels changes in psychosis. The affective flattening factor would in turn represent those negative symptoms that do not respond to antipsychotic treatment and may in fact be drug-induced. Thus, it appears that in the search for primary negative symptoms, a first step would be to focus on this affective cluster of symptoms rather than lack of motivation. In cases where the newer antipsychotics (i.e., those with fewer extrapyramidal side effects) are being used or in the case of a drug-free evaluation, we suggest that these symptoms may be a relatively good measure of primary negative symptoms, which could then be tested over time for longitudinal stability. In addition, this cluster of symptoms may be specific targets for future improvements in pharmacological treatment.

While it may be tempting to control statistically for the effects of extrapyramidal symptoms in order to eliminate these effects, we suggest that this approach be used with caution. It is clear to a certain extent that these two observational concepts, negative symptoms and extrapyramidal side effects, overlap considerably, and that drug-induced negative symptoms may in fact be a component of extrapyramidal side effects and vice versa. In addition, it is likely that patients with affective flattening are more susceptible to medication effects and extrapyramidal side effects, which would indicate that neither process is more “primary” but that these behavioral manifestations may have a similar source. Thus, we suggest that the two syndromes may not be statistically independent but are conceptually independent, and that controlling for the variance in negative symptoms associated with extrapyramidal side effects would be inappropriate if the two syndromes are indeed caused by the same mechanism. The only way to assess the natural course of these two syndromes is by removing or reducing the causes of extrapyramidal side effects pharmacologically, through evaluation of patients when they are drug free or evaluation of the newer antipsychotics, combined with careful and rigorous longitudinal observation.

The idea that affective flattening and poverty of speech may be more stable over time and less responsive to treatment has been demonstrated through previous longitudinal studies

(12) and was discussed in Crow’s reevaluation of the two-syndrome concept

(45). Mueser et al.

(14) noted time effects for anhedonia and avolition, but not affective flattening or alogia, in a 1-year follow-up. McGlashan and Fenton

(22) also showed changes over time for all subscales of the SANS except affective flattening in an extended (approximately 5-year) follow-up study. In addition, Fenton and McGlashan

(20) noted that among the six prominent cross-sectional subtype classification systems, affective flattening and poverty of speech are the only symptoms shared by all. These authors had previously proposed

(15) that these symptoms be added as a criterion for a diagnosis of schizophrenia, which has become a reality with DSM-IV.

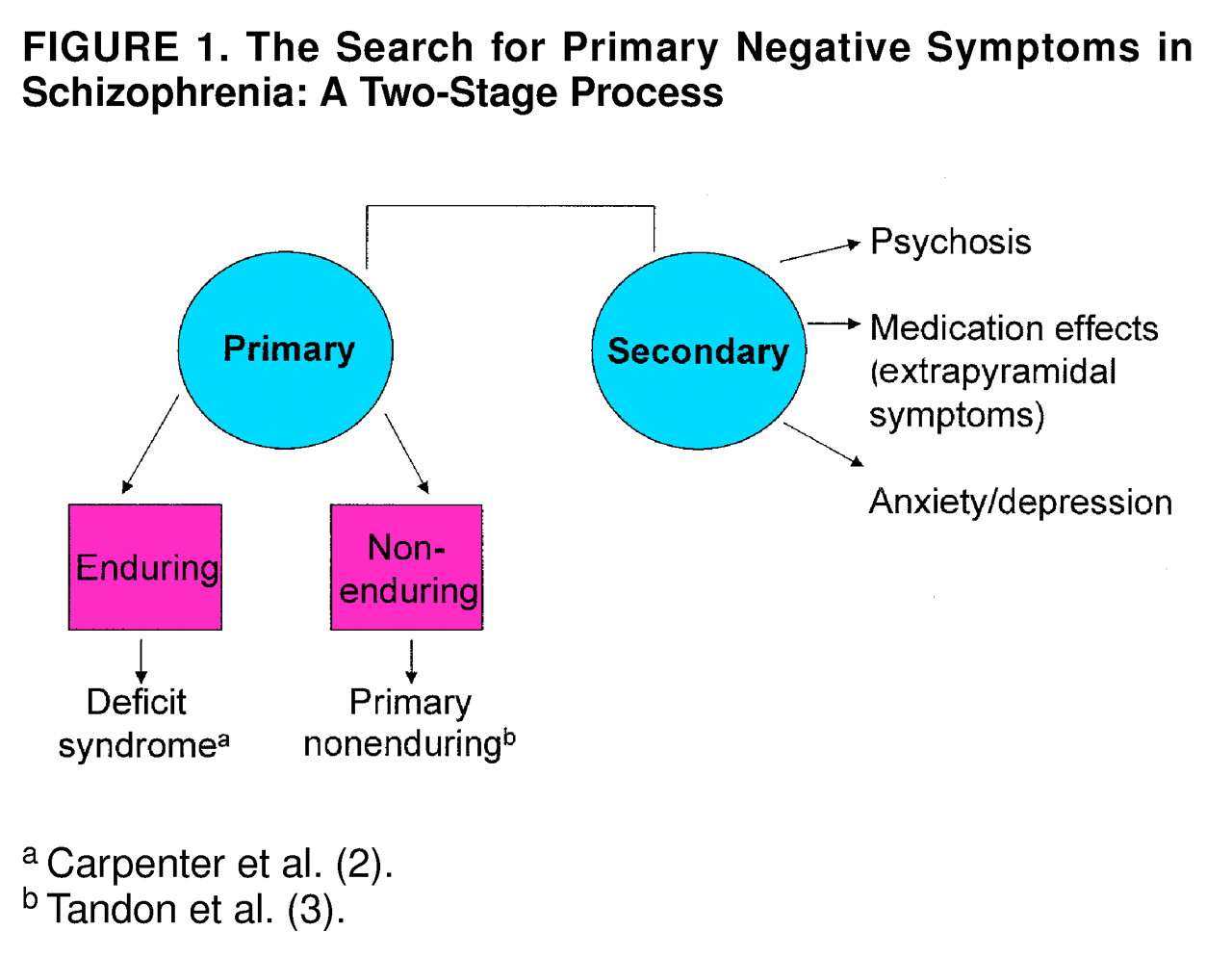

The terms “primary” and “secondary” need clarification at this time. Specifically, the differentiation must be made between primary enduring negative symptoms (i.e., the deficit syndrome) and what may be termed primary nonenduring negative symptoms

(3), i.e., those that may be primary to the illness but still fluctuate with exacerbation. We propose that the empirical differentiation of primary negative symptoms is a two-stage process. Medication and exacerbation effects, as well as effects of other secondary sources, must first be uncovered and, if necessary, controlled statistically. The aspects of negative symptoms that are not associated with secondary effects must then be tested for longitudinal stability (

figure 1.). While these two stages may be evaluated retrospectively with appropriate analytic techniques, it is not clear that the secondary nature of symptoms can be determined reliably by using clinical judgment at the time of assessment

(46). In addition, it is not clear what frequency of longitudinal assessment should be used to prove stability; if the primary/secondary distinction is valid, it should hold up under the more rigorous scrutiny of monthly or weekly assessments. Future research on independent samples is needed to validate both the findings of the current study and the possible longitudinal stability of these measures.