Notwithstanding some cyclical variation, there has been a distinct general decline over the last quarter century in the percentage of U.S. medical students choosing to specialize in psychiatry

(1). The consistent rates of 7% to 10% per year in the years following World War II began to fall in the early 1970s and now have declined to approximately 3%

(1). During the last decade alone (1988–1998) the number of U.S. medical students matching to psychiatric residencies has declined by 42.5%

(2). Several hypotheses have been posited to account for this decline

(1,

3). It is not known whether this decline indicates that medical students entering medical training are less attracted to psychiatry, or whether the medical school experience is increasingly deterring interest in psychiatry, or whether both processes occur.

To differentiate deterring factors that exist prior to medical school from those that develop during medical school, it is important to assess the attitudes of U.S. medical students who are naive of the medical school experience. In the early 1970s, Fishman and Zimet

(4) reported that 13% of freshmen medical students at two U.S. medical schools indicated that psychiatry was their top specialty choice for vocation. No comparable study has been conducted since that time. In the present study, we surveyed freshman medical students at three southwestern United States medical schools within the first 2 weeks of their freshman medical year.

METHOD

Medical students entering their freshman year in 1994 at three medical schools (University of California, San Diego; University of California, Irvine; and University of Texas at Houston) were asked to participate in a study being conducted to assess the attitudes of medical students toward various medical specialties. Willing participants anonymously completed a survey regarding their attitudes toward careers in various medical specialties. In each case the survey was conducted during the freshman orientation period or within the first week of classes.

The survey was developed by two of the authors (D.F. and C.Y.M.) and was based on questionnaires developed by others for similar purposes

(3,

5,

6). The survey required 15–20 minutes to complete and consisted of 24 items; the majority of the items were in a 5-point Likert scale format, whereas some were in an open-ended format. (The questionnaire is available on request from Dr. Feifel). The items explored five areas:

1. The demographic backgrounds of the student;

2. Which generic factors students considered important in their choice of a specialty;

3. The degree to which students were considering possible careers among various medical specialties (family practice, internal medicine, pediatrics, surgery, obstetrics/gynecology, and psychiatry);

4. The degree to which students found various specialties (internal medicine, surgery, pediatrics, and psychiatry) attractive as careers with regard to the following aspects: financial reward, lifestyle, job satisfaction, enjoyable work, degree to which patients are helped, prestige, interesting subject, challenging work, drawing on all aspects of medical training, reliable scientific basis, rapidly advancing understanding and treatment of illness, bright and interesting future;

5. Their estimates of the degree to which others (e.g., classmates, physicians, community) respected the skills of physicians in various specialties (internal medicine, surgery, pediatrics, and psychiatry).

For each applicable item in this questionnaire students were asked to provide a response for several specialties, including psychiatry. Students were blind to the specialty of the investigators and the specialty focus (psychiatry) of the study. The questionnaire was distributed and collected through the office of the dean of each medical school.

Ratings of attractiveness of each specialty with regard to various aspects were treated as continuous data

(7) and were analyzed by using a two-tailed, repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), with medical school as a between-subject grouping factor and specialty as within-subject grouping factor. A significant overall ANOVA was followed by individual pairwise comparisons that used a two-tailed Student’s t test corrected by the Bonferroni method for multiple comparisons. Other ratings by students were treated as descriptive; these included which generic factors they considered important in their choice of a specialty, the degree to which they were considering various medical specialties as possible careers, and their estimates of the degree to which others (e.g., classmates, physicians, community) respected the skills of physicians in various specialties.

RESULTS

The rates of response were 119 (60%) from the University of Texas at Houston; 34 (40%) from the University of California, Irvine; and 70 (56%) from the University of California, San Diego. The total group size of 223 constitutes a 52% response rate across all three schools.

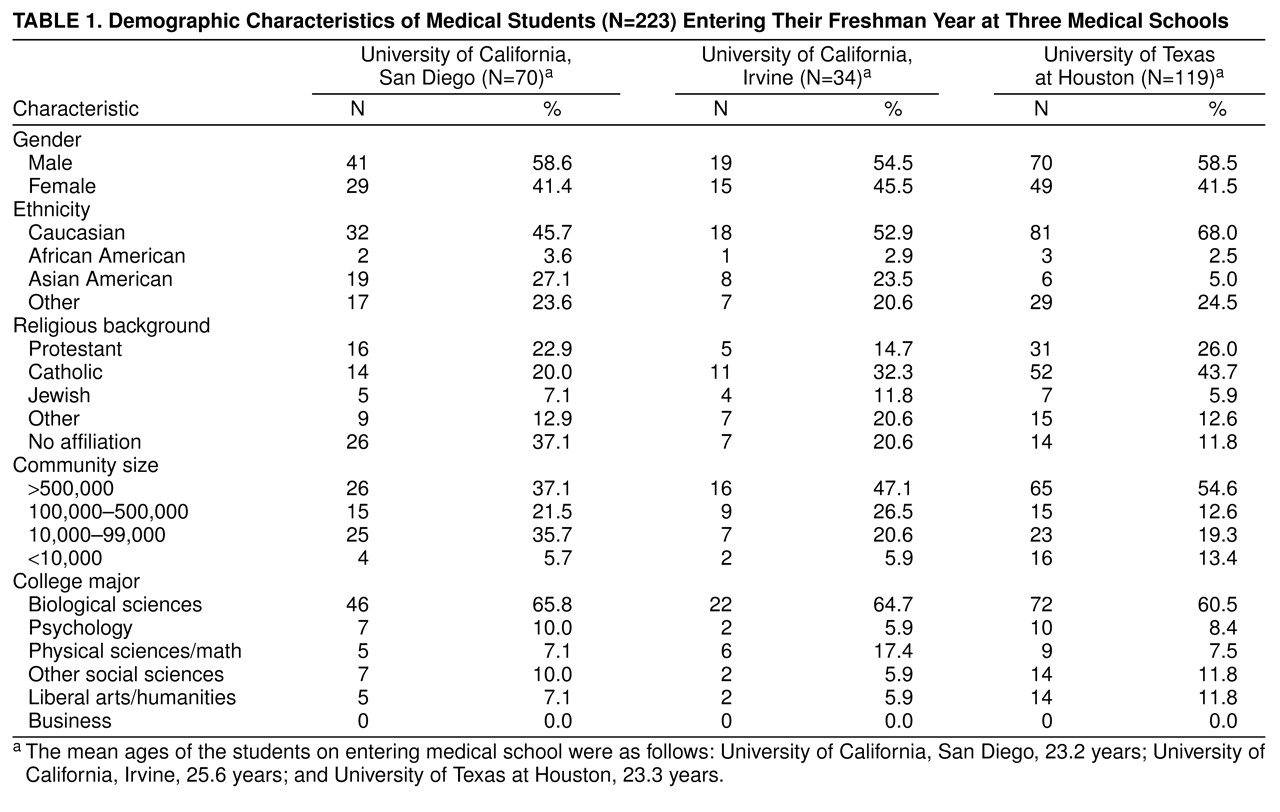

Table 1 displays the demographic characteristics of the subjects in each of the three freshman classes. The freshman class of the University of Texas at Houston was composed of notably fewer Asian Americans than were the classes at the University of California, Irvine and San Diego, and had notably fewer students describing themselves as having no religious affiliation. Otherwise, the subjects who responded did not appear to differ significantly in age, gender distribution, size of community of origin, or college majors across the three freshman classes. A comparison of attitudes of medical students toward various specialties and aspects of career choice revealed no significant differences across schools for any of the aspects queried. As a result, data averaged across all three schools are presented.

Students were asked to rate the degree to which each of three aspects of medicine interested them (1=not at all, 5=very much). Students in all three schools endorsed similar interests, ranking interpersonal interactions with patients the highest (rating of 4.7), the diagnosis and treatment of disease second (rating of 4.5), and scientific research third (rating of 3.3). Students were also asked to rate the importance of five possible factors in choosing a specialty as a vocation. They mostly strongly rated the ability to help patients (rating of 4.7), followed by interesting and challenging work (rating of 4.6), lifestyle factors (rating of 4.4), financial reward (rating of 3.2), and prestige (rating of 2.7).

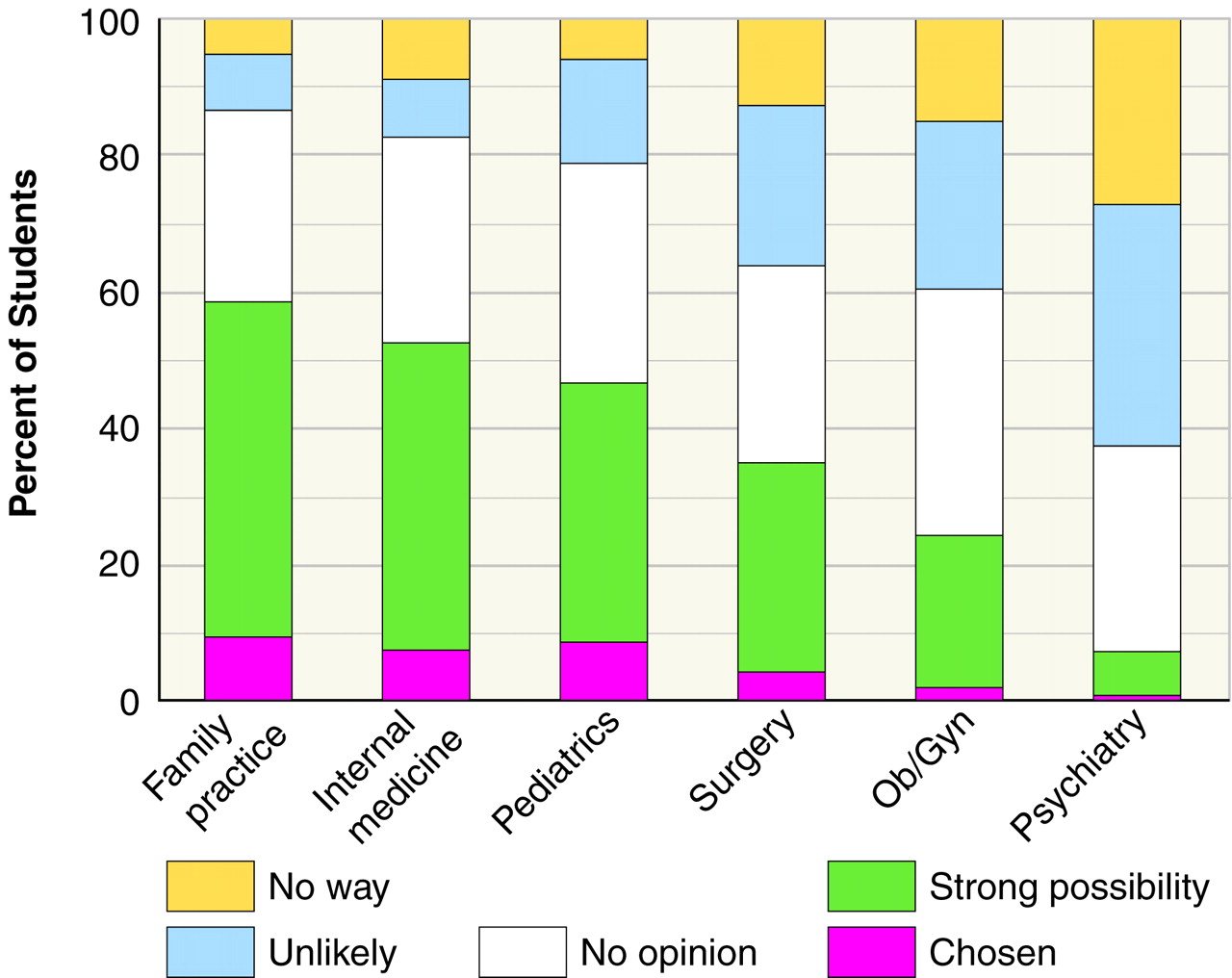

Figure 1 illustrates the degree to which freshman medical students were considering various specialties as prospective career options. For each specialty approximately one-third of the students indicated that they had not developed a strong opinion. Among the remaining respondents, consideration of specialties differed greatly, with psychiatry ranking poorest by any ordinal measure. Only one student of 221 (0.5%) identified psychiatry as the career of choice, and only 16 (7.2%) considered it a strong possibility; these were the smallest numbers among any of the specialties in both of these categories. Similarly, 78 (35.3%) considered it unlikely that they would choose psychiatry as a career, and 60 (27.1%) had already definitively ruled it out (“no way”); these were the highest proportions among any of the specialties surveyed for both of these categories.

A review of the open responses given by students who definitively ruled out a career in psychiatry, a priori, suggests that two major themes contributed to their position. Approximately 25% (N=35) of those who responded identified the patient population as a major aversive factor, citing the undesirability and emotional drain of interacting with psychologically impaired patients. Approximately 60% of respondents (N=85) identified the field itself as a major aversive factor, citing a lack of scientific foundation or a lack of clinical efficacy of psychiatric treatments or both, which made a career in psychiatry seem excessively “frustrating.” The remainder (approximately 15% [N=21]) simply cited a total lack of interest in the field.

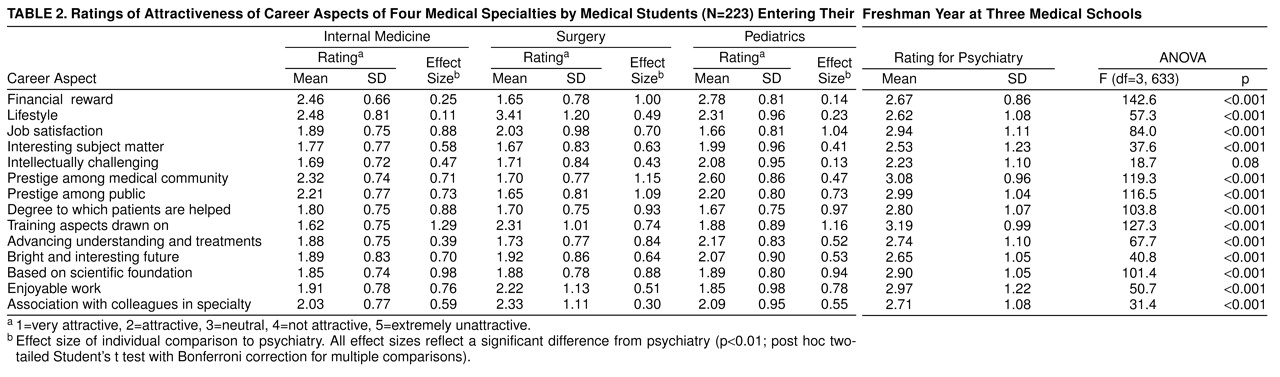

Ratings of attractiveness in regard to various career aspects of the four specialties—internal medicine, surgery, psychiatry, and pediatrics—revealed significant differences across specialties for all aspects measured (

table 2). Individual pairwise comparisons revealed that students rated psychiatry significantly lower than each of the other three specialties in regard to the degree to which it was a satisfying job, enjoyable work, prestigious, helpful to patients, dealing with an interesting subject matter, intellectually challenging, drawing on all aspects of medical training, based on a reliable scientific foundation, expected to have a bright and interesting future, and a rapidly advancing field of understanding and treatment. Psychiatry was rated as significantly less attractive than internal medicine and surgery, but not pediatrics, in regard to financial reward. Psychiatry was rated as significantly more attractive than surgery, and no different from internal medicine or pediatrics, with respect to lifestyle.

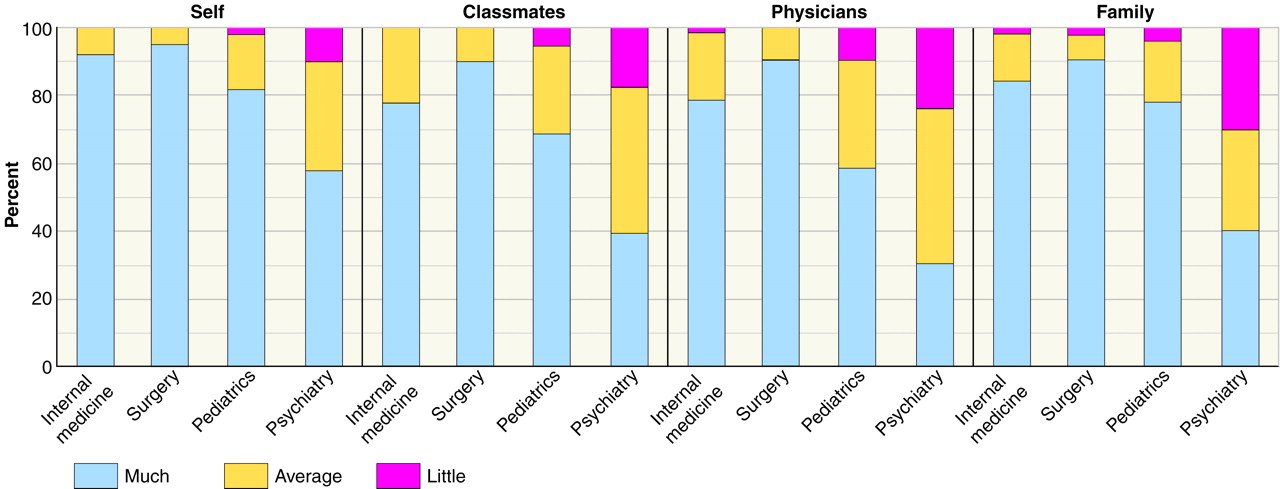

When asked to estimate the degree to which they, their family, their classmates, and other physicians respected the skills and knowledge of physicians in each specialty, students rated psychiatrists substantially lower than each of the other three types of specialists (

figure 2).

DISCUSSION

While the response rate achieved in this study (52%) is comparable to that of other studies of medical student attitudes by survey

(3,

6), it represents a limitation regarding the ability to generalize from these results. On the other hand, the lack of significant differences in the responses across the three schools surveyed supports the generalizability of these findings. The results suggest that medical students bring to their medical training a very negative view of psychiatry, compared to other specialties. The consistency of psychiatry’s terminal ranking in virtually all areas surveyed indicates that this field continues to be perceived as outside the mainstream of medical practice. This is consistent with findings from previous studies of the attitudes of medical students at various stages of their medical education, which reveal a general negative attitude toward psychiatry

(3,

6). The present study demonstrates that these negative views are formed before formal medical training.

While differences in research methodology make longitudinal comparisons of medical student attitudes difficult, two previous studies of medical students early in their freshman year serve as interesting comparisons to this study. In the early 1970s, Fishman and Zimet

(4) surveyed freshmen medical students at the beginning of the academic year at two medical schools, and they found that 13% of the students identified psychiatry as their top specialty choice for vocation. A decade later, Friedman and McGuire

(5) assessed the freshman medical class at the University of California, Irvine, within the first half of the academic year and found that 11% of the students were very interested in psychiatry as a possible career and that 28% expressed a negative interest. By comparison, our data indicate that less than 8% of the students were very interested in psychiatry and that of these, only 0.5% considered it their top choice, whereas 62% of the students expressed a negative consideration of psychiatry as a career (unlikely or “no way”). On the basis of these comparisons, it seems that there has been a distinct decline over the past two decades in the attraction of freshman medical students to careers in psychiatry. This view is consistent with a prematriculation survey conducted by the Association of American Medical Colleges

(8), which revealed that first-year medical students in 1992 were less likely to plan psychiatric careers than were first-year medical students in 1987 and 1988. Such results support the “admissions hypothesis”

(3) for the decline in medical graduates entering psychiatric training, which posits that students entering medical school are increasingly less inclined to positively view careers in psychiatry. Little is known regarding the factors that influence the specialty choice of psychiatry before medical school. Zimny and Sata

(9) evaluated several possible factors retrospectively and found that psychology-based college courses, mental health work experience, and experience with someone having a psychiatric disorder were the pre-medical school factors that led to the most positive view of psychiatry.

As for the apparent erosion of interest in psychiatry among new medical students, several possible reasons exist. Undergraduates inclined toward professional careers in mental health may be increasingly choosing other, nonmedical, clinical training paths to this goal

(10). Similarly, shifts over the past two decades in the demographic characteristics of medical students could be resulting in a greater proportion of medical students from sociocultural backgrounds less favorably inclined toward careers in psychiatry

(11,

12). Perhaps the medical school selection process has become increasing biased against selecting candidates with the educational backgrounds (e.g., humanities) that may characterize the most positively inclined applicants. Finally, perhaps medical students entering medical school are merely reflecting an increasingly hostile attitude held by contemporary American society toward psychiatry and psychiatrists

(13–

16).

Students reported significantly less respect for the professional skills of psychiatrists and also estimated that their classmates possessed even less respect for psychiatrists and that physicians at their medical school held psychiatrists in even lower esteem. It is very unlikely that within their first few days of medical school, these students had any exposure to specific attitudes regarding psychiatry held by either their classmates or the medical teaching faculty. Beginning medical students appear to perceive that the process involved in becoming a physician will move them toward an even more negative view of psychiatry.

Attitudes assessed in this survey reflect primarily a subjective value system and cannot objectively be deemed accurate or inaccurate. However, some of these attitudes appear to reflect inaccurate or incomplete knowledge, and it is these negative attitudes that may be corrected through the course of medical education. For example, students perceive that psychiatric treatments are less effective than those available in other specialties. There is sufficiently strong scientific evidence available to counter this perception and to suggest that the effectiveness of psychiatric treatments, on the whole, is equal to or superior to that of conventional treatments in other specialty fields

(17). On the other hand, patients with diseases that are difficult to treat are found in all medical practices, and the current data suggest that students entering medical school view negatively the prospect of working with these populations. This points to a need for increased teaching about such issues across specialty boundaries during medical school.

Other beliefs about psychiatry seem to be due to erroneous or insufficient knowledge. For example, students only weakly endorsed the belief that psychiatry is a rapidly advancing field and saw it as having a less bright and less interesting future than all the other specialties surveyed. It is hard to identify a specialty that in the last decade has seen an explosion in the understanding and treatment of illness in its purview comparable to that in the field of psychiatry. Considering pharmacological treatments alone, the advent of newer antidepressants (e.g., serotonin uptake inhibitors and atypical antidepressants), mood stabilizers (anticonvulsants), and atypical antipsychotics has revolutionized the standard pharmacological treatment of mental illness.

Studies of the stability of specialty choices among medical students suggest that a large proportion of medical students will change their specialty preferences from the freshman to senior years

(18–

20). Evidence indicates that attitudes toward any specialty can be improved as a result of a skillful and enthusiastic presentation of that specialty

(21,

22). This suggests that medical school experience has a significant effect on shaping ultimate career choices and that negative a priori attitudes of new medical students toward psychiatry can be ameliorated. Negative beliefs based on inaccurate perceptions of objective evidence (e.g., success rate of psychiatric treatments) should be specifically targeted in the preclinical and clinical psychiatric curricula.

The potential benefit of remediating such inaccurate beliefs held by new medical students is highlighted by their reported general motivations and interests regarding becoming physicians. These reported motivations and interests are fully consistent with careers in psychiatry. For example, high prestige and high financial reward, two aspects that a career in psychiatry is not as likely to provide as other specialties, were rated least important by students as considerations for choosing a specialty. In contrast, career features viewed by freshman medical students to be most important included the ability to have interpersonal interactions with patients, to help their patients, to have an attractive lifestyle, and to be engaged in work that is highly interesting and challenging. These are all features that characterize a career in psychiatry.

CONCLUSIONS

Medical students enter medical school with distinctly negative attitudes toward a career in psychiatry compared with other specialties. Current attitudes seem to represent a further erosion from already negative attitudes toward psychiatry that have been recorded among new medical students over the past two decades, and they may account to some degree for the declining numbers of medical students entering residencies in psychiatry. Some of these negative views are subjective and less vulnerable to remediation, whereas others appear to be more objectively refutable through education. Such a process of correction may yield greater interest in psychiatry as a career because students value many features that characterize a career in psychiatry. Whether their medical school experience corrects, exacerbates, or leaves unaltered such views is the focus of an ongoing longitudinal study.