Subjects

Men and women between the ages of 18 and 55 were eligible to become probands for the study. Exclusion criteria were deafness, blindness, psychosis, inadequate command of the English language, or a full-scale IQ less than 80 as measured by the IQ estimated from the block design and vocabulary subtests of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scales—Revised. No ethnic or racial group was excluded. We used two ascertainment sources to recruit ADHD probands: referrals to psychiatric clinics at Massachusetts General Hospital and advertisements in the greater Boston area. We recruited potential probands without ADHD through advertisements in the greater Boston area. We ascertained and assessed the probands and all available biological children, parents, and siblings. The study was approved by the institutional review board at Massachusetts General Hospital. Every subject 18 and older provided signed informed consent. Younger relatives of the probands provided signed assent, and the parents provided signed informed consent. The confidentiality of the subjects was protected throughout the study.

Assessment Measures

Trained lay interviewers, blind to ascertainment status, interviewed all adults with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV

(11) and modules from the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children Epidemiologic Version (K-SADS-E)

(12) . When we asked questions about childhood disorders, the subjects were first queried about childhood symptoms, and if they were present, they were asked about continuation of these symptoms into adulthood and the emergence of others. Age at onset was defined as the first emergence of impairing symptoms. Interviewers collected information for psychiatric diagnoses in child relatives (ages 6 to 18) with the K-SADS-E. Before interviewing for the study, interviewers completed a 4-month training program that included mastery of the instruments, learning about DSM-IV criteria, watching training tapes, observing interviews performed by experienced raters, rating several subjects under the supervision of the project coordinator and completing practice interviews. Throughout the study, they were supervised by board-certified child and adolescent psychiatrists or licensed psychologists. This supervision included weekly meetings and additional consultations, as needed. During the study, all interviews were audiotaped for random quality control assessments.

For all child relatives, psychiatric data were collected from the mother when available. In addition, child relatives 12 and older were directly evaluated. Final diagnostic assignment was based on the structured psychiatric interview. Initial diagnoses were prepared by the study interviewers and were then reviewed by a diagnostic committee of board-certified child and adolescent psychiatrists or licensed psychologists. The diagnostic committee was blind to each subject’s ascertainment group, all data collected from other family members, and all nondiagnostic data (e.g., cognitive functioning). Diagnoses were made for two points in time: lifetime and current (past month).

The interviewers had been instructed to take extensive notes about the symptoms for each disorder. These notes and the structured interview data were reviewed by the diagnostic committee so that the Committee could make a best-estimate diagnosis, as described by Leckman et al.

(13) . Definite diagnoses were assigned to subjects who met all diagnostic criteria. Diagnoses were considered definite only if a consensus was achieved that criteria were met to a degree that would be considered clinically meaningful. By “clinically meaningful,” we mean that the data collected from the structured interview indicated that the diagnosis should be a clinical concern because of the nature of the symptoms, the associated impairment, and the coherence of the clinical picture.

The interviewers were blind to the subject’s baseline ascertainment group, the ascertainment site, and all prior assessments. The interviewers had undergraduate degrees in psychology and were extensively trained. First they underwent several weeks of classroom-style training, learning interview mechanics, diagnostic criteria, and coding algorithms. Then they observed interviews by experienced raters and clinicians. They subsequently conducted at least six practice (nonstudy) interviews and at least three study interviews while being observed by senior interviewers. Trainees were not permitted to conduct interviews independently until they executed at least three interviews that achieved perfect diagnostic agreement with an observing senior interviewer. A senior investigator (J.B.) supervised the interviewers throughout the study. We computed kappa coefficients of agreement by having experienced board-certified child and adult psychiatrists and licensed clinical psychologists diagnose subjects from audiotaped interviews. On the basis of 500 assessments from interviews of children and adults, the median kappa coefficient was 0.98. Kappa coefficients for individual diagnoses were ADHD (0.88), conduct disorder (1.00), major depression (1.00), mania (0.95), separation anxiety (1.00), agoraphobia (1.00), panic (0.95), substance use disorder (1.00), and tics/Tourette’s disorder (0.89).

Statistical Analyses

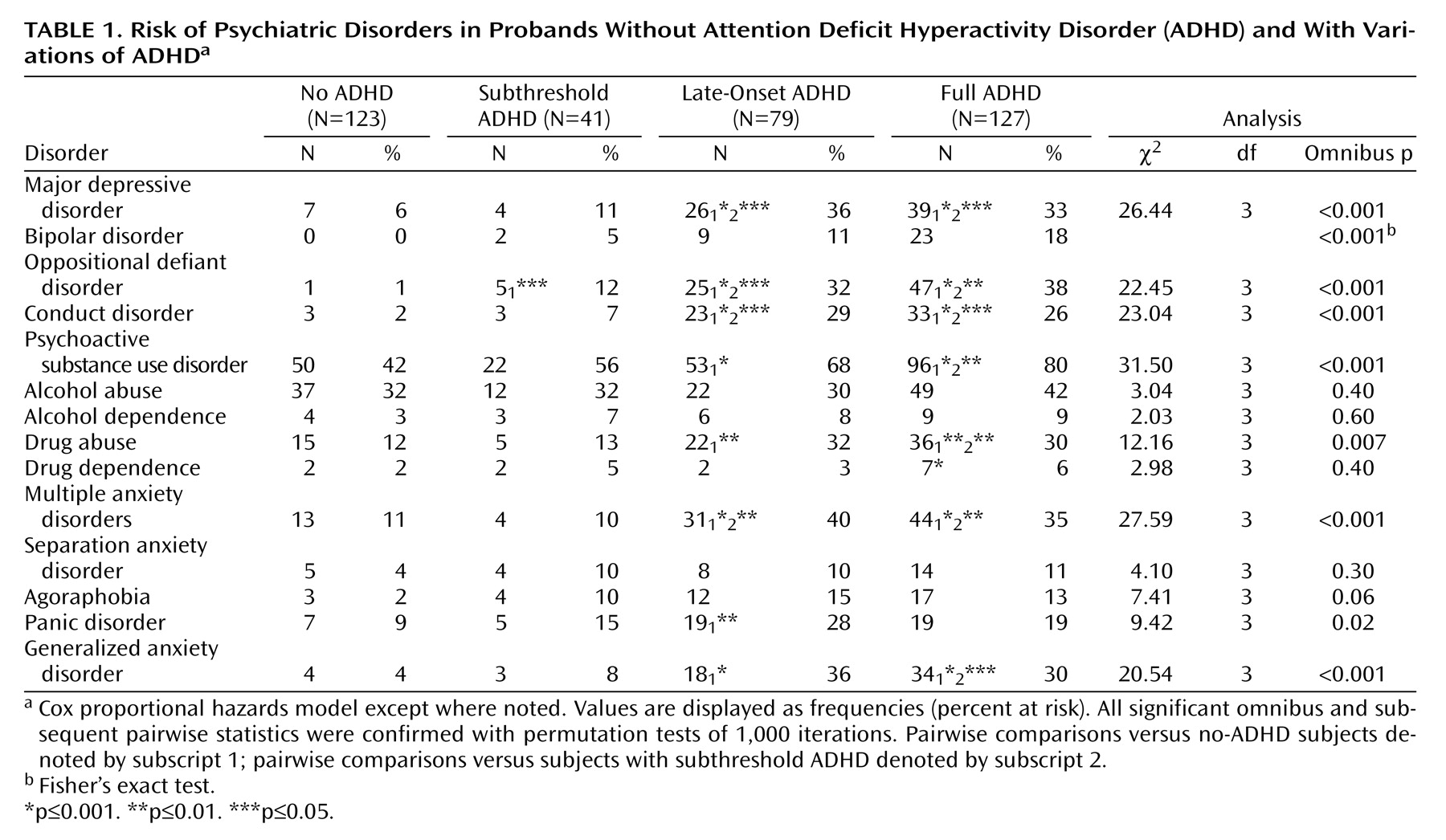

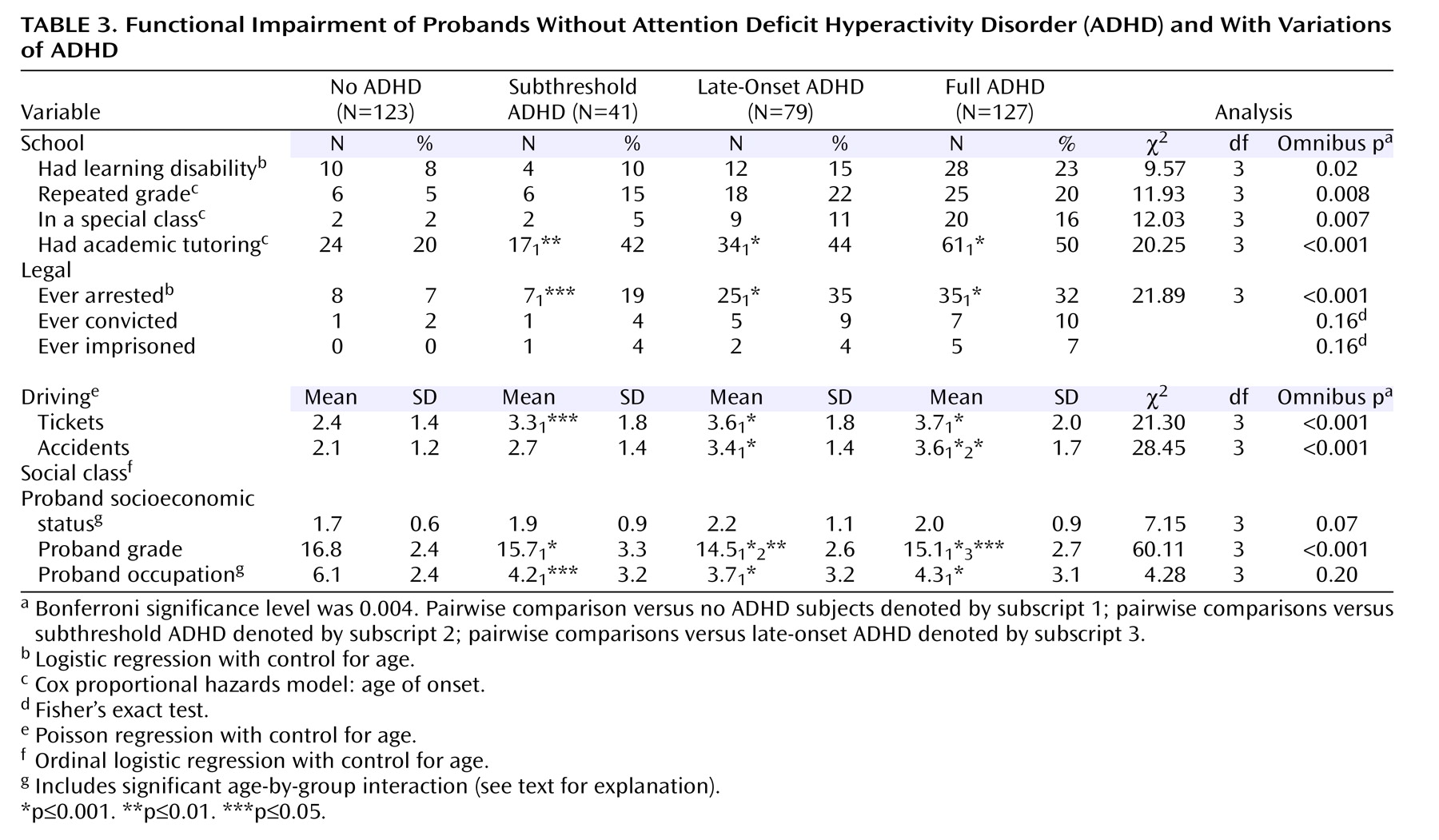

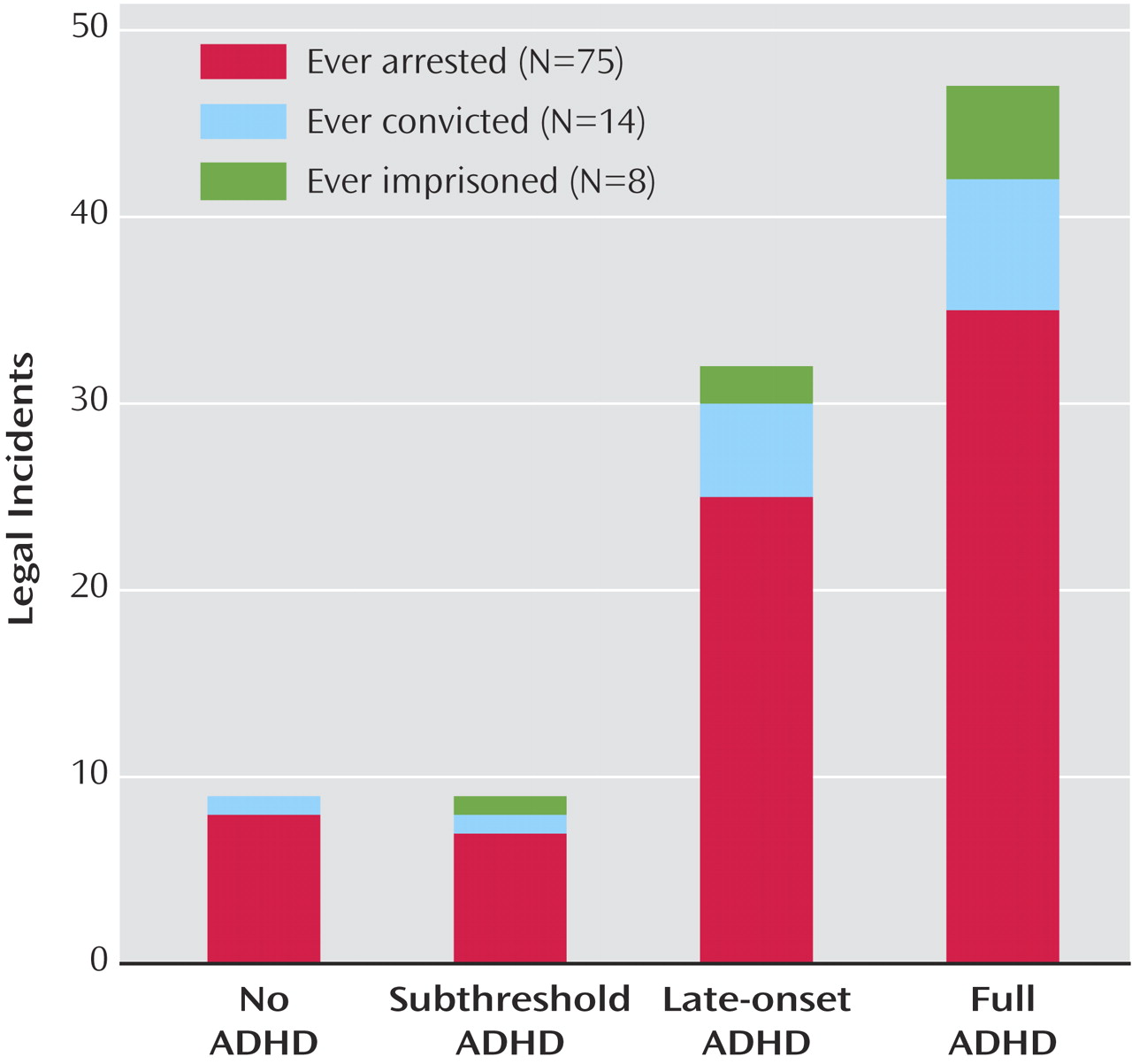

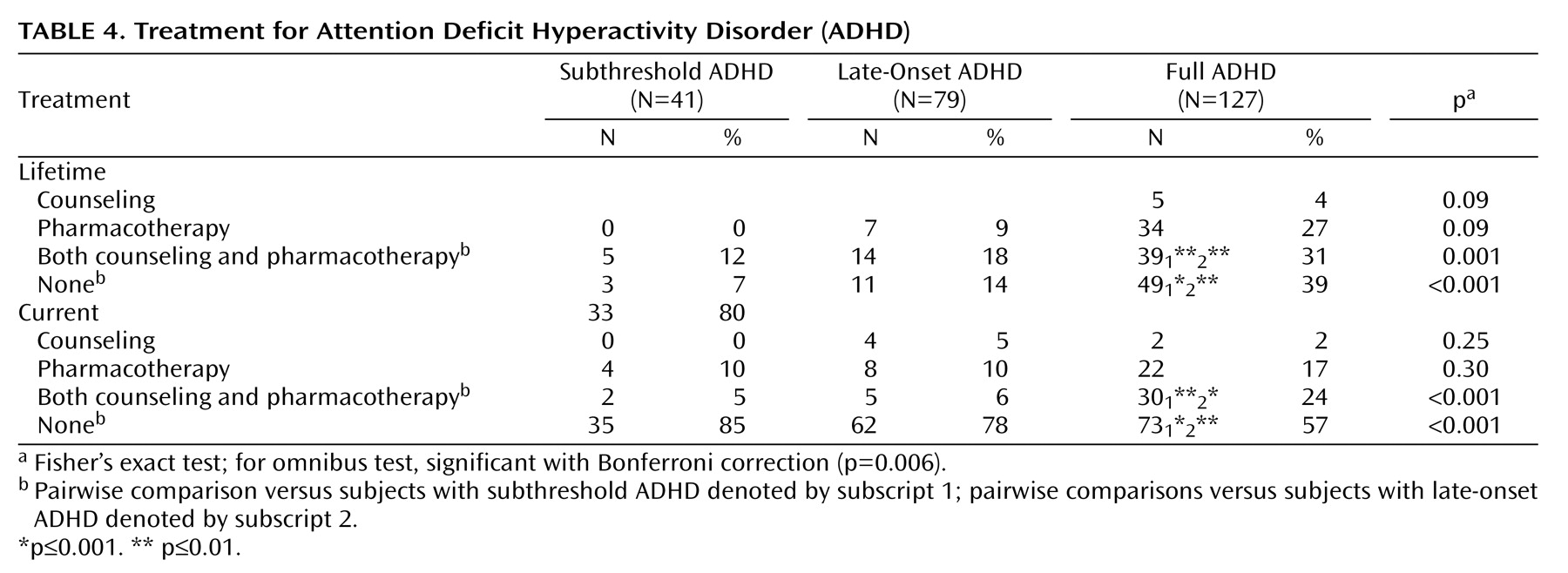

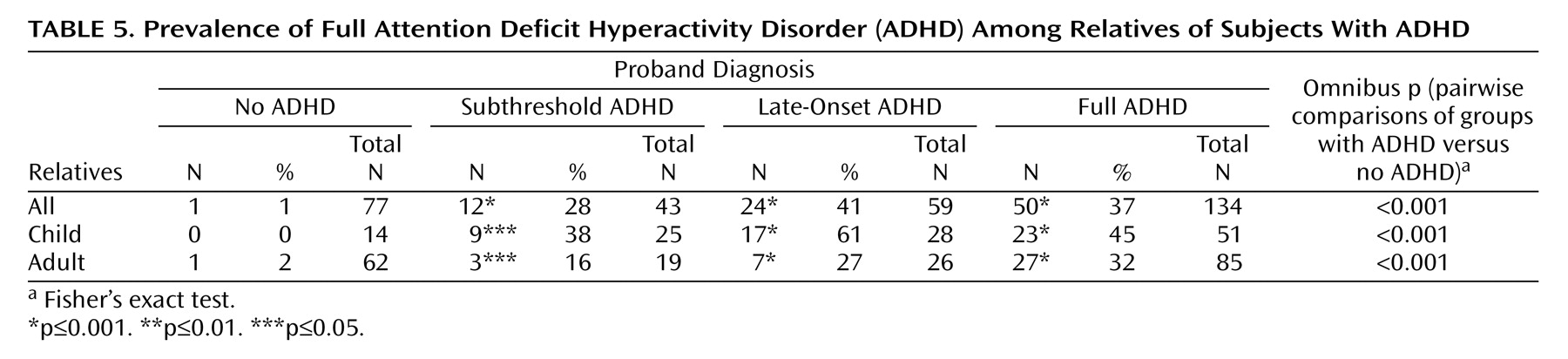

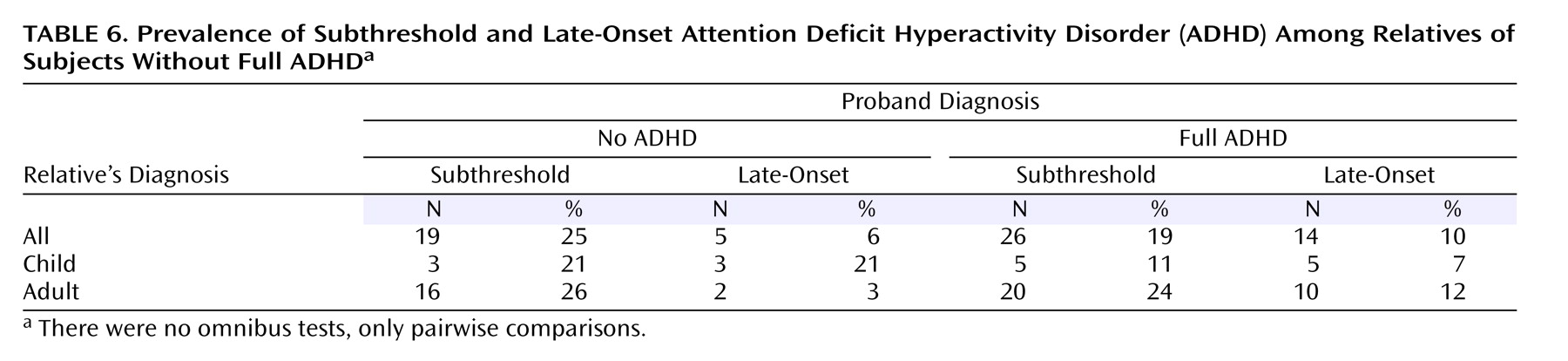

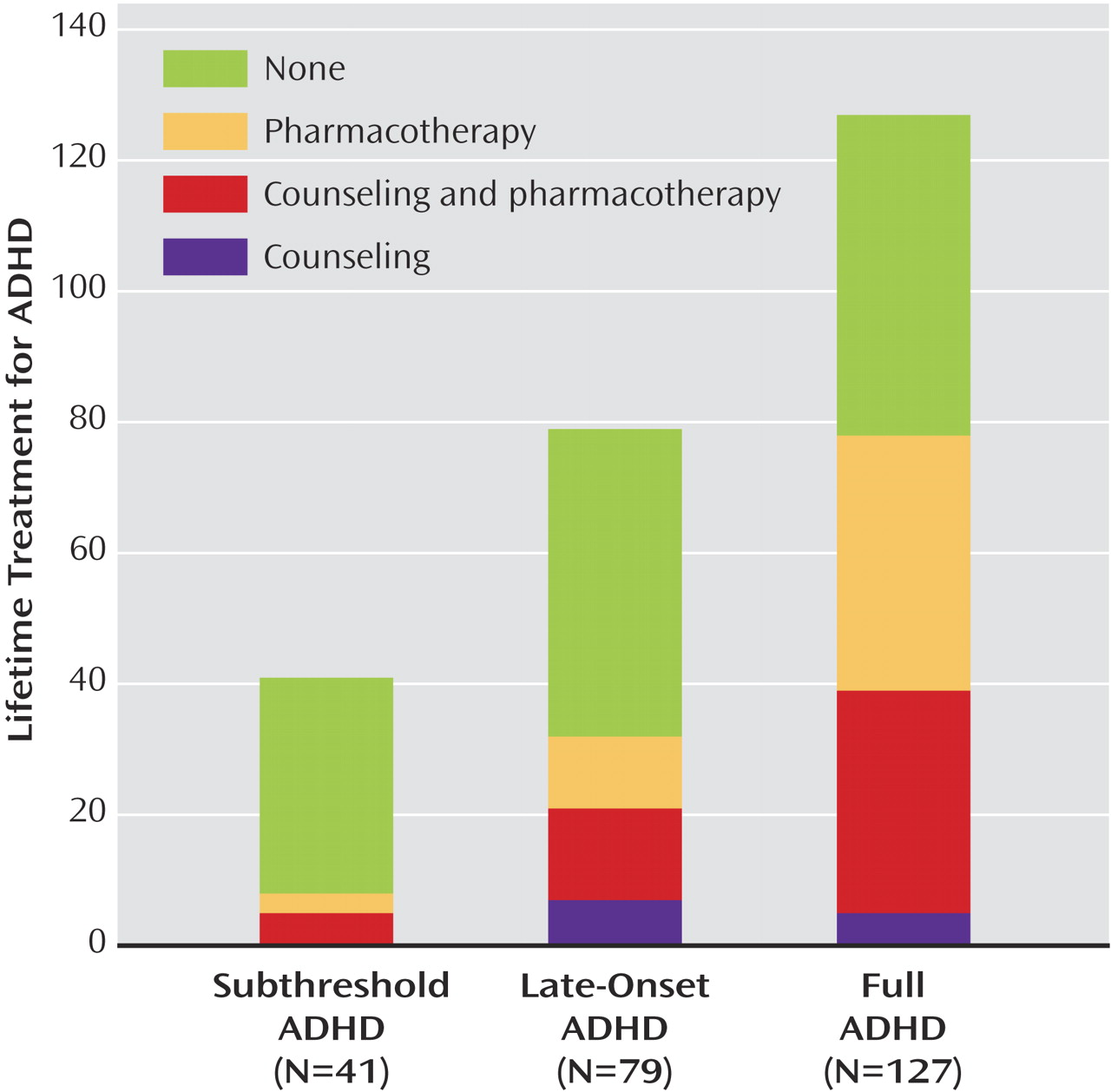

Our analyses used logistic regression for binary outcomes, ordinal logistic regression for ordinal outcomes, Poisson regression for count data, multinomial logistic regression for categorical outcomes, and Gaussian regression for continuous outcomes. For each psychiatric disorder in

Table 1, we used Cox proportional hazard models to predict age of onset and proportion at risk. We then permuted group membership across subjects and recalculated our omnibus and pairwise statistics for permutation tests. Permutation testing calculates the probability of achieving a result through random assignment of subjects into groups by measuring the number of recalculated results greater than the observed statistic during a prescribed number of iterations. Using permutation tests allowed us to reinforce our results with low frequencies of psychiatric disorders in our groups without ADHD and subthreshold ADHD. For the same reasons, we used Fisher’s exact test to analyze differences in the frequency of subjects receiving different treatment options, numbers of relatives with full ADHD, and subthreshold ADHD across ADHD diagnosis groups.

Because multiple members of a single family cannot be considered independent of one another because they share genetic, cultural, and social risk factors, we used Huber-White robust estimates of variance in analyses of relatives so that p values would be accurately estimated. We used the following strategy to balance our risk for type I and type II errors when we adjusted for multiple comparisons. For each domain of analysis (as defined by the tables), we applied Bonferroni correction to the omnibus test for each variable in the domain. If that was significant, we used the 0.05 alpha level to assert significance for pairwise comparisons.