On the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test, the mean standard score was 60.3 (SD=12.7, range=40–97) for participants with mild mental retardation, 48 (SD=10.5, range=40–84) for those with moderate mental retardation, and 106 (SD=7.4, range=86–126) for comparison subjects. Eighty-six percent with mild and 96% with moderate mental retardation scored in the low range of the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales composite score.

For analysis, the 19 items of the ACC-RCT were grouped into the four consent capacity categories.

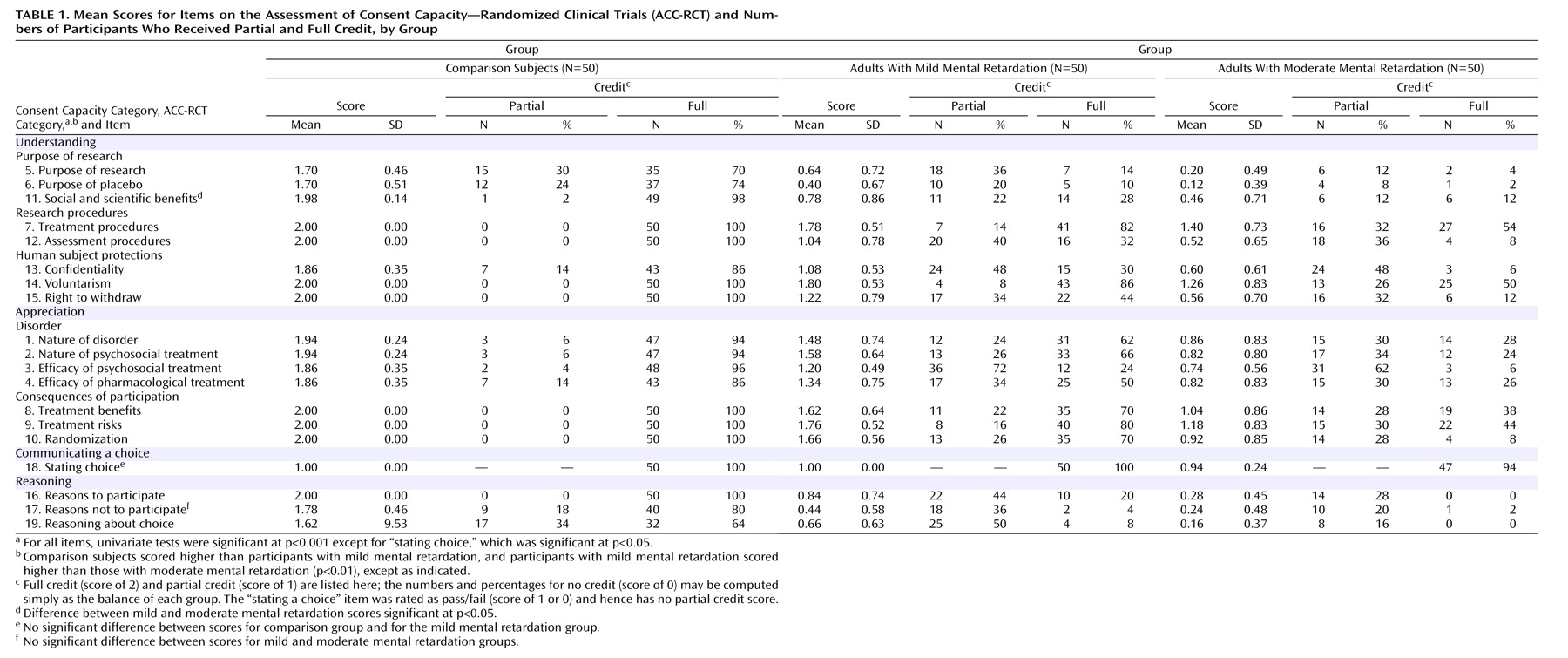

Table 1 presents the mean scores for each item on the ACC-RCT for each group, along with the numbers and percentages of participants in each group whose responses received full or partial credit. Significant effects of intellectual functioning were found for each item, at p<0.001 except for the item on communicating a choice, which was significant at p<0.05. Following a significant MANOVA, contrast tests assuming unequal variance indicated that the scores for the comparison subjects were significantly higher than those for participants with mild mental retardation, and these in turn were higher than scores for participants with moderate mental retardation (p<0.05), with two exceptions: participants with mild mental retardation and those with moderate mental retardation did not differ in their ability to provide reasons against participation, and the three groups did not differ in communicating a participation choice. All but three participants with mental retardation communicated a participation choice. In the end, 12% of those with mild mental retardation, 18% of those with moderate mental retardation, and 6% of comparison subjects decided that the protagonist should not participate in the hypothetical study.

Within-Group Differences in Consent Capacity

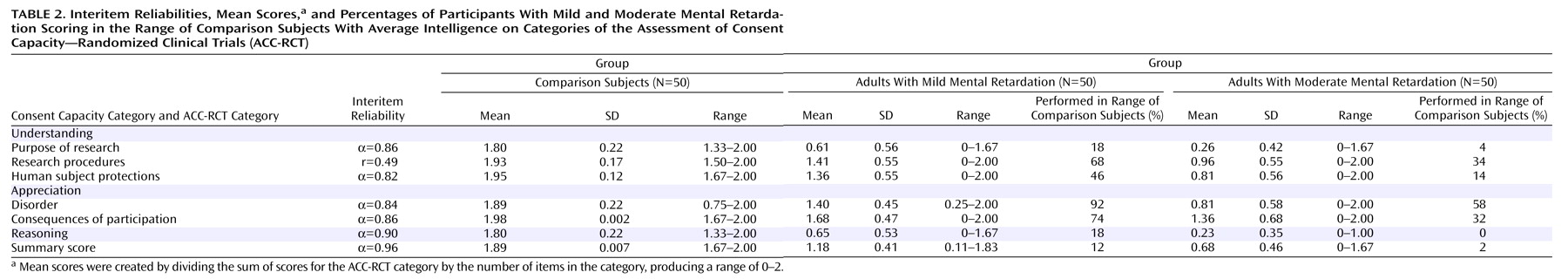

As

Table 2 shows, reasoning and understanding the purpose of research were more difficult than other ability categories for all three groups (for the comparison group, t=61.26, df=49, p<0.001; for the mild mental retardation group, t=26.38, df=49, p<0.001; for the moderate mental retardation group, t=13.07, df=49, p<0.001). Following a nonsignificant interaction between item difficulty and mental retardation, correlated t tests found similar patterns of items across the comparison group and the combined mental retardation groups. Participants found it easier to understand societal research benefits than the research purpose (within groups, t=4.58, df=49, p<0.01; between groups, t=2.66, df=99, p<0.01), easier to understand voluntary participation than confidentiality (within groups, t=2.82, df=49, p<0.01; between groups, t=9.58, df=99, p<0.01), easier to understand reasons for participation than reasons against participation (within groups, t=3.35, df=49, p<0.01; between groups, t=3.68, df=99, p<0.01), and easier to understand reasons for participation than giving a reasoned explanation for participation choice (within groups, t=5.07, df=49, p<0.01; between groups, t=2.68, df=99, p<0.01).

Participants with mental retardation found it easier to understand treatment procedures than assessment procedures (t=10.04, df=99, p<0.001), easier to understand the purpose of research than the purpose of a placebo (t=2.5, df=99, p<0.05), easier to appreciate research risks than research benefits (t=2.01, df=99, p<0.05), and easier to appreciate the protagonist’s disorder and the vignette’s description of a behavioral intervention than appreciating that a psychosocial and a pharmacological treatment had not reduced the symptoms of the protagonist’s behavior problem (t=3.04, df=99, p<0.01). Only the group with moderate mental retardation found it more difficult to appreciate the consequences of random assignment to treatment or placebo than to appreciate either treatment risks or benefits (t=2.15, df=49, p<0.05).

Table 2 provides full-scale scores based on the combined average of the 18 items reflecting understanding, appreciation, and reasoning that are presumed to reflect cognitive skills associated with consent comprehension (the “communicating a choice” item was not included). In separate analyses for the mild and moderate mental retardation groups, we examined correlations between the ACC-RCT full-scale score and intelligence scores (the verbal and matrices scales of the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test; the Vineland adaptive behavior subscales [communication, daily life, socialization, and motor functioning]; medical history [aggressive behavior, psychopharmacological medications, and number of comorbid psychiatric diagnoses]; and consent experiences [for medical treatment, medication, and nonmedical decision making]).

For the mild mental retardation group, only the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test verbal score correlated with the full-scale score (r=0.47, df=48, p<0.001). By contrast, the moderate mental retardation group’s full-scale score was correlated with the Kaufman verbal score (r=0.37, df=48, p<0.01), the Kaufman matrices score (r=0.32, df=47, p<0.05), the Vineland daily living subscale score (r=0.41, df=47, p<0.01), and the Vineland socialization subscale score (r=0.33, df=47, p<0.05).

To further examine the influence of these variables on the moderate mental retardation group’s full-scale ACC-RCT scores, regression models with a constant included in the equation were built with Vineland daily living subscale score, the Kaufman verbal score, the Kaufman matrices score, and the Vineland socialization subscale score regressed onto the full-scale score. Model 2, using the Vineland daily living subscale score and the Kaufman verbal score, produced the best fit (adjusted R 2 =0.25; R 2 change=113, F change=7.201, df=1, 46, p=0.01).

For both mental retardation groups, summary scores reflecting understanding of research procedures, human subject protections, appreciation, and reasoning were significantly correlated with one another, suggesting that common intellectual processes underlie different aspects of consent comprehension (r’s ranged from 0.46 to 0.83, df=48, p<0.01). Not surprisingly, a history of aggressive behavior, psychopharmacotherapy, and psychiatric diagnoses were also significantly correlated with one another (r’s ranged from 0.37 to 0.64, df=48, p<0.01). However, none of these mental health and treatment indices were related to participants’ history of consenting to medical treatments, except for a significant negative correlation between aggressive behavior and consent experience in the moderate mental retardation group (r=–0.32, df=48, p<0.05). Counter to expectations based on an experiential model of consent capacity, no associations were observed between medical or consent histories and any of the consent capacity summary scores.