In patients with schizophrenia, the mortality rate by suicide is high, with a lifetime risk of about 5%

(1) . The rate of suicidal attempts is higher and varies between 20%–40%

(2,

3) . Previous attempts are significant predictors of later attempts and completed suicide. In addition, current depression, feelings of hopelessness, and drug abuse are repeatedly identified risk factors

(4 –

6) .

There is a striking difference in suicide rates between first-episode and chronic schizophrenia patient groups, with first admissions having rates three times higher

(1) . In addition, between 15%–26% have made at least one suicide attempt by their first treatment contact and 2%–11% at least one more during their first year of treatment

(7 –

9) . The seriousness of suicide attempts is high for patients with schizophrenia spectrum psychoses

(3,

10) . Treatment interventions can reduce suicide risk from the initiation of treatment onward but will not affect the high level of risk in undetected cases

(11,

12) . For some patients, suicidal behavior may be the event precipitating the first treatment contact

(9,

13) . Strategies bringing patients with first-episode psychosis into treatment earlier may reduce risk, but we know of no empirical study addressing this question.

Method

The study’s four health care sectors (population 655,000) established equivalent assessment and treatment programs for patients with first-episode psychosis. Two sectors added an early psychosis detection program that consisted of two elements: 1) repeated information campaigns directed at the general population, schools, and first-line health care personnel and 2) easily accessible early detection clinical teams capable of rapid assessment and triage.

The major targets for the information campaign were the general public, health care professionals, and high school teachers and students. The campaign aimed at increasing the knowledge about psychiatric disorders in general and early signs of psychotic disorders in particular. The main issues were to counteract stigmatization of people with severe mental disorders and to change help-seeking behavior through information on available resources and the possibilities of a positive outcome.

At the start of the project/information campaign, all households in the early detection sectors received a free brochure with information on early psychotic disorders and the aim of the early detection and intervention project. The main message was that “Psychiatric disorders have at least one thing in common with somatic disorders: the chance of getting well increases with earlier treatment.” The brochure also included the telephone number for the low-threshold detection teams, with a presentation including photos of the staff. The subsequent public information campaign consisted of advertisements repeated approximately once each month in key local medias. The advertisements consisted of thematic ads in the district’s two largest local newspapers and commercials in local cinemas and local radio and TV stations. In addition, free postcards (

Figure 1 ) and stickers with the project logo and the detection team’s phone numbers were distributed in places frequented by youths and young adults such as cinemas and public libraries. At the same time, health care professionals such as the area’s general practitioners were offered tailored educational workshops with information on recognition and treatment of early psychosis, including a training video that showed a patient with a recent onset of psychosis (portrayed by an actress) and a rating scale of psychotic signs and symptoms. The area’s high schools were visited twice each semester and were offered tailored educational sessions on early psychosis, with an emphasis on an active attitude toward help-seeking and advice on how to get in contact with the detection teams. The early detection program had a noticeable and immediate effect, with an increased number of referrals to the early detection teams coinciding with each campaign initiative

(14,

15) .

For this study, there were no differences in age, gender distribution, main income levels, rates of unemployment, or yearly rates of completed suicides between the health care sectors’ populations. The only demographic difference was that the communities without the early detection program had more immigrants than the early detection communities (12% versus 4%) (p<0.001, Fisher’s exact test).

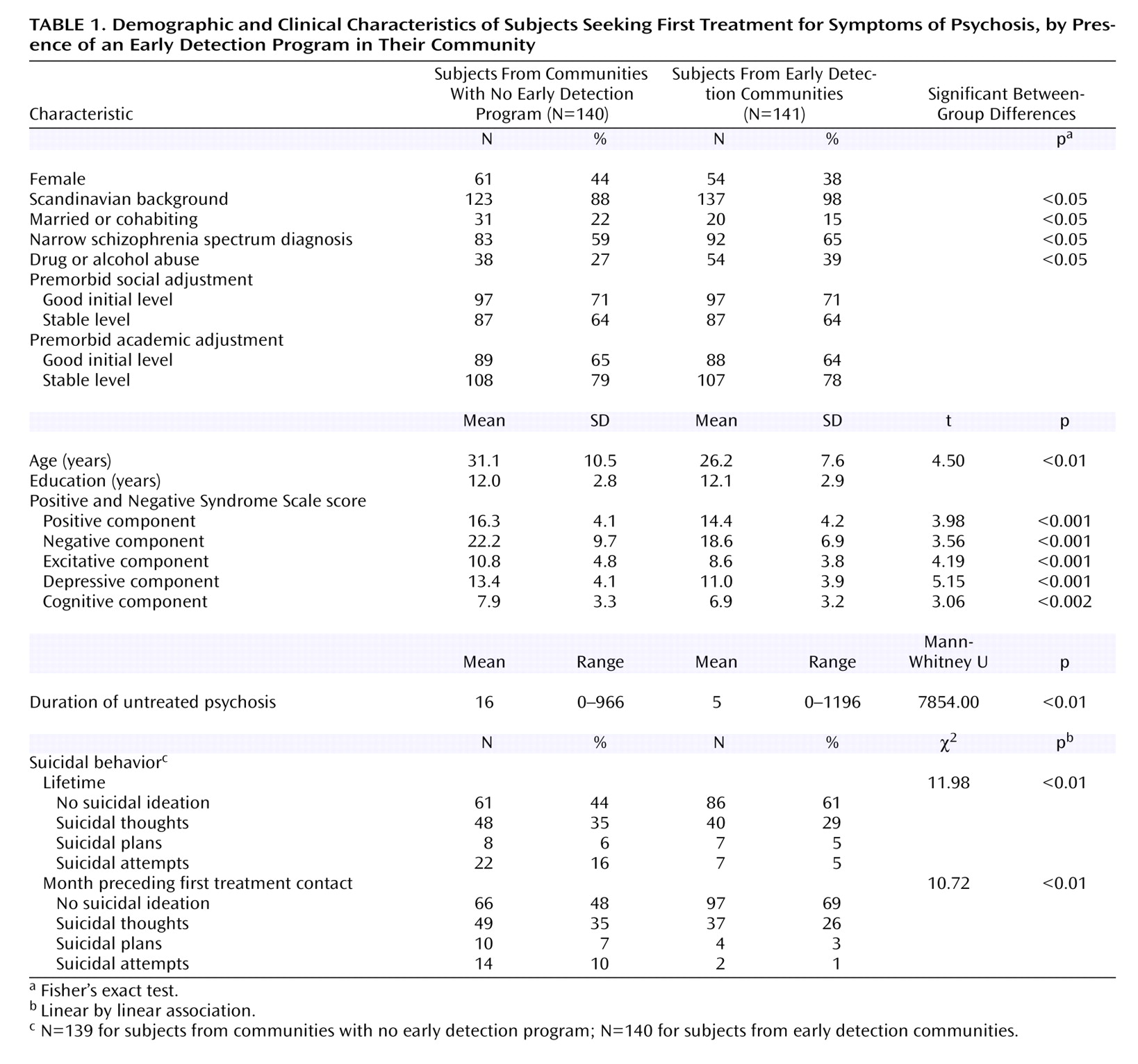

Study inclusion criteria were living in the catchment area of one of the four health care areas; 18–65 years of age; meeting DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder (constituting the narrow schizophrenia spectrum disorders) or brief psychotic episode, delusional disorder, affective psychosis with mood-incongruent delusions, or psychotic disorder not otherwise specified; actively psychotic (score of four or more on at least one of positive subscale items 1 (delusions), 3 (hallucinatory behavior), 5 (grandiosity), or 6 (suspiciousness/persecution) or general subscale item 9 (unusual thought content) from the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale); no previous adequate treatment; no neurological or endocrine disorders with relationship to the psychosis; no contraindications to antipsychotic medication; ability to understand/speak one of the Scandinavian languages; IQ over 70; and willing and able to give informed consent. Patient enrollment started at the same time as the early detection program and included all eligible, consecutive patients over the next 4 years. Individuals with psychosis-like symptoms seeking help from a psychiatric service (N=874) were screened, 378 met the study inclusion criteria, and 281 (141 from the early detection communities, 140 from communities without the program) provided written informed consent

(14,

16) . Patients from early detection communities had a shorter duration of untreated psychosis and lower symptom levels, were slightly younger, and were more likely to be Scandinavian, have a narrow schizophrenia diagnosis, and have a history of drug abuse than patients from the communities without the program (

Table 1 ).

All evaluations were made by clinically experienced and trained research personnel using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (to obtain a diagnosis), the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (to assess symptom levels), the Drake scale (to determine drug and alcohol misuse)

(17), and the Premorbid Adjustment Scale (to assess premorbid adjustment)

(18) . The Premorbid Adjustment Scale was first divided into social and academic domains and then further into initial (childhood) level of adjustment and subsequent course development

(19) . Duration of untreated psychosis was measured as time from onset of psychosis (first week with symptoms that corresponded with a score of four or more on at least one of positive subscale items 1 (delusions), 3 (hallucinatory behavior), 5 (grandiosity), or 6 (suspiciousness/persecution) or general subscale item 9 (unusual thought content) from the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale) until start of adequate treatment

(14) . Suicidal behavior was assessed by asking the patients at the index diagnostic interview whether they had experienced any suicidal thoughts, plans, or attempts in the preceding month and whether they had experienced any suicidal thoughts, plans, or attempts earlier in their lifetime. Information was cross-checked with the medical charts. Severe suicidality was defined as plans and attempts, based on previously shown high associations between plans, attempts, and later completed suicides

(20) . All raters were trained to reliability in the use of study instruments; reliability tests were blind and based on randomly drawn study participants (see Melle et al.

[14] for details).

Analyses were made with the statistical package SPSS (version 12.0). All tests were two-tailed, with level of significance set at p≤0.05. Duration of untreated psychosis was not normally distributed, and all analyses that included the duration of untreated psychosis were nonparametric if possible or else duration of untreated psychosis was logarithmically transformed. Binary logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate predictors and rule out confounders for risk of serious suicidal behavior at start of first treatment. Variables were entered if they were differentially distributed between the two areas, if they had a statistically significant association with suicidality in bivariate analyses, or were previously identified as potential predictors. They were entered hierarchically with “Coming from an area without the early detection program” at the last step. The final model was examined for nonlinearity and for the effects of influential observations and outliers.

Results

There were high levels of suicidality both at start of first treatment and in the period before. However, patients coming from the early detection communities reported significantly less suicidal behavior than patients from communities without the program (

Table 1 ). The difference was particularly marked for the severe forms of suicidal behavior (suicidal attempts and suicidal plans: 4% [N=6] versus 17% [N=24], respectively [p<0.001, Fisher’s exact test]; suicidal attempts only: 1% [N=2] versus 10% [N=14] [p=0.002, Fisher’s exact test]).

There were significant correlations between suicidal behavior at first treatment contact and previous suicidal behavior (r=0.66), more depressive symptoms (r=0.23), and poorer satisfaction with life (r=0.25) (all p<0.001). While less robust, there were also significant correlations between suicidal behavior at first treatment contact and being single (r=0.15), diagnosis outside of the narrow schizophrenia spectrum (r=0.12), longer duration of untreated psychosis (r=0.12), poorer initial levels of premorbid academic adjustment (r=0.14) and social adjustment (r=0.17), and deterioration in premorbid social adjustment (r=0.13) (all p<0.05). No correlations with suicidal behavior at first treatment contact were seen for age, gender, immigrant status, drug abuse, or positive or negative symptoms.

Since the difference in suicidal behavior between the early detection communities and the communities without the program could have been mediated through differences in background variables, multivariate analyses were done to explore confounder effects. A binary logistic regression analysis with “Serious suicidality: Presence of plans or attempts at index contact” as dependent variable showed a statistically significant influence for only two variables: “previous plans and attempts” (odds ratio: 6.22, 95% CI=2.36–16.34) and “coming from a community without the early detection program” (odds ratio: 4.96, 95% CI=1.44–17.06). Repeating the analyses with “suicidal attempts” alone as the dependent variable reproduced equivalent results (for “coming from a community without the early detection program”: odds ratio: 5.20, 95% CI=1.05–25.74).

Discussion

This study confirms that suicidal behavior is present in the early phases of psychotic disorders and in many cases precedes the first treatment contact. While patients from communities that did not have the early psychosis detection program showed rates of suicidal behavior in the expected range, the early detection group had significantly lower rates. The study thus indicates that an early detection program, by lowering the threshold for first treatment contact and bringing patients into treatment earlier, can reduce rates of serious suicidal behavior at the point of first contact. The difference was not mediated by differences in lifetime suicidality. While it was not possible in the present study to directly link decreased suicidality with the early psychosis detection program, it is interesting that it appears that facilitating treatment engagement at lower symptom levels seems to have a separate effect on suicidality beyond the decrease in duration of untreated psychosis.

Reducing suicide is a World Health Organization priority. Risk reduction programs in general youth populations and the U.S. Armed Forces have given indications of positive results

(21,

22), and another systematic review cited positive effects on suicide rates of educating general practitioners about patients with depression

(23) . However, the results of these studies have been questioned because of design issues. To our knowledge, ours is the first study to demonstrate that targeted interventions directed toward high-risk clinical groups can reduce severe suicidality and that early detection and intervention have the potential of reducing one of the most dangerous and permanent complications of schizophrenia.