Major depressive disorder is associated with substantial morbidity, mortality, family burden, and health care costs

(1) . In double-blind efficacy trials typically conducted with outpatients who have uncomplicated, nonchronic, nonrefractory major depressive disorder, initial treatment with antidepressant medications appears to lead to remission in only 35%–47% of patients

(2,

3) . In a recent report, among representative patients in primary and psychiatric care, roughly 30% reached remission after 8–12 weeks of therapy with citalopram

(4) . Consequently, a large majority of patients will warrant subsequent treatment regimens in order to achieve remission.

Most second or third treatment steps following initial antidepressant failure have been evaluated in uncontrolled trials, typically in psychiatric outpatients with minimal general medical comorbidity recruited as volunteers and treated in research clinics

(5), which hampers the generalizability of findings to clinical practice. There is a clear paucity of data on whether switching antidepressants for the third time is a clinically useful strategy for depressed patients who have not had adequate responses to two prior antidepressant treatments. In a recent uncontrolled efficacy trial, switching to a third antidepressant led to remission rates of 36% to 50%, similar to the rates of 48% to 50% observed with the first and second antidepressant trials within the same study

(6) . These results suggest that the strategy of switching antidepressants following two consecutive antidepressant treatment failures has robust efficacy. However, an uncontrolled effectiveness trial with 115 patients found only a 21% remission rate for the third antidepressant trial

(7) . Only one trial has included participants who had not received adequate benefit from two initial antidepressant treatments who were then randomly assigned to at least two potentially effective third-step treatments (venlafaxine or paroxetine). An overall remission rate of 27% after 4 weeks of treatment was found

(8) . In that study, however, nonresponse to the first antidepressant trial was only ascertained historically, and the second treatment had to have been prescribed by the investigator at an effective dose only 4 weeks or more before the first day of the study, or 2 weeks or more if a safety problem had caused discontinuation.

This report focuses on the outcomes of participants who were randomly assigned to one of two third-step antidepressant switch strategies (mirtazapine or nortriptyline) as part of the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial

(11,

12) . STAR*D is the first trial to evaluate the relative effectiveness of switching to these two antidepressants for primary and psychiatric care patients with major depressive disorder who did not adequately benefit from an initial prospective trial with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) and a subsequent antidepressant medication. The equipoise stratified randomized design allowed patients at specific steps to select the treatment strategies they considered acceptable and from which their random assignment would be determined

(13) . This study assessed the effectiveness of switching to mirtazapine compared with switching to nortriptyline for treatment of major depressive disorder following two consecutive unsuccessful antidepressant regimens.

Method

Participants

The institutional review boards at the STAR*D National Coordinating Center, the Data Coordinating Center, all regional centers, and relevant clinical sites as well as the NIMH Data Safety and Monitoring Board (Bethesda, Md.) approved and monitored the protocol. All participants provided written informed consent at enrollment into the initial (Level 1) treatment with citalopram and at enrollment into each subsequent treatment step, including the third-step (Level 3) antidepressant switch strategies reported herein.

Outpatients with a primary diagnosis of nonpsychotic major depressive disorder, per DSM-IV and confirmed by a checklist completed by the clinical research coordinators, were enrolled between July 2001 and April 2004 at 18 primary and 23 psychiatric practice settings serving both public and private sector patients. Advertising for participants was proscribed. Broad inclusion and minimal exclusion criteria were used to maximize the generalizability of findings

(4,

11,

12) . More specifically, excluded patients were those with bipolar or psychotic disorders, primary diagnoses of obsessive-compulsive or eating disorders, general medical conditions contraindicating the use of protocol medications in the first two treatment steps, substance dependence (only if it required inpatient detoxification), a clear history of nonresponse or inability to tolerate any protocol treatment during the first two treatment steps for the current major depressive episode, and those who were pregnant or breastfeeding

(4,

11,

12) .

Eligible participants for second-step treatment (Level 2) had either not achieved remission or were not able to tolerate treatment with citalopram (up to 12 weeks). Nonremission following citalopram was defined as a score of >5 on the clinician-rated, 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS-C

16 )

(14 –

17) obtained at the last citalopram treatment visit.

Participants in the second step (Level 2) of STAR*D agreed to random assignment to one of four alternate monotherapy options (bupropion [sustained release], cognitive therapy, sertraline, or venlafaxine [extended release]) or one of three citalopram augmentation options (bupropion [sustained release], buspirone, or cognitive therapy)

(13) . Thus, Level 2 of STAR*D evaluated the comparative effectiveness of different medication switch strategies

(18) and augmentation options

(19) . Those achieving remission in Level 2 entered a 12-month naturalistic follow-up phase. Those achieving response but not remission (QIDS-C

16 score of 6–8) at this or subsequent levels were encouraged to enter the next level, but they could opt to enter the naturalistic follow-up. Those with an unsatisfactory response entered Level 3. Participants with an unsatisfactory response to both citalopram (Level 1) and to cognitive therapy during Level 2, whether cognitive therapy was used as a switch strategy or an augmentation option, entered Level 2A, which compared the effectiveness of two medication switch strategies (bupropion [sustained release] or venlafaxine [extended release]). Level 2A ensured that all participants who entered Level 3 had an unsatisfactory response to two different antidepressants. Those with remission or a satisfactory response to Level 2A entered the 12-month follow-up, whereas those with an unsatisfactory response entered Level 3. Therefore, eligible participants for third-step treatment entered Level 3 if they had not achieved remission or were unable to tolerate Level 2 or Level 2A treatments. Study participants were not required to meet major depressive disorder criteria at the time of entry into Level 3, as long as they had met major depressive disorder criteria at entry into Level 1 and had not adequately responded or been able to tolerate previous levels.

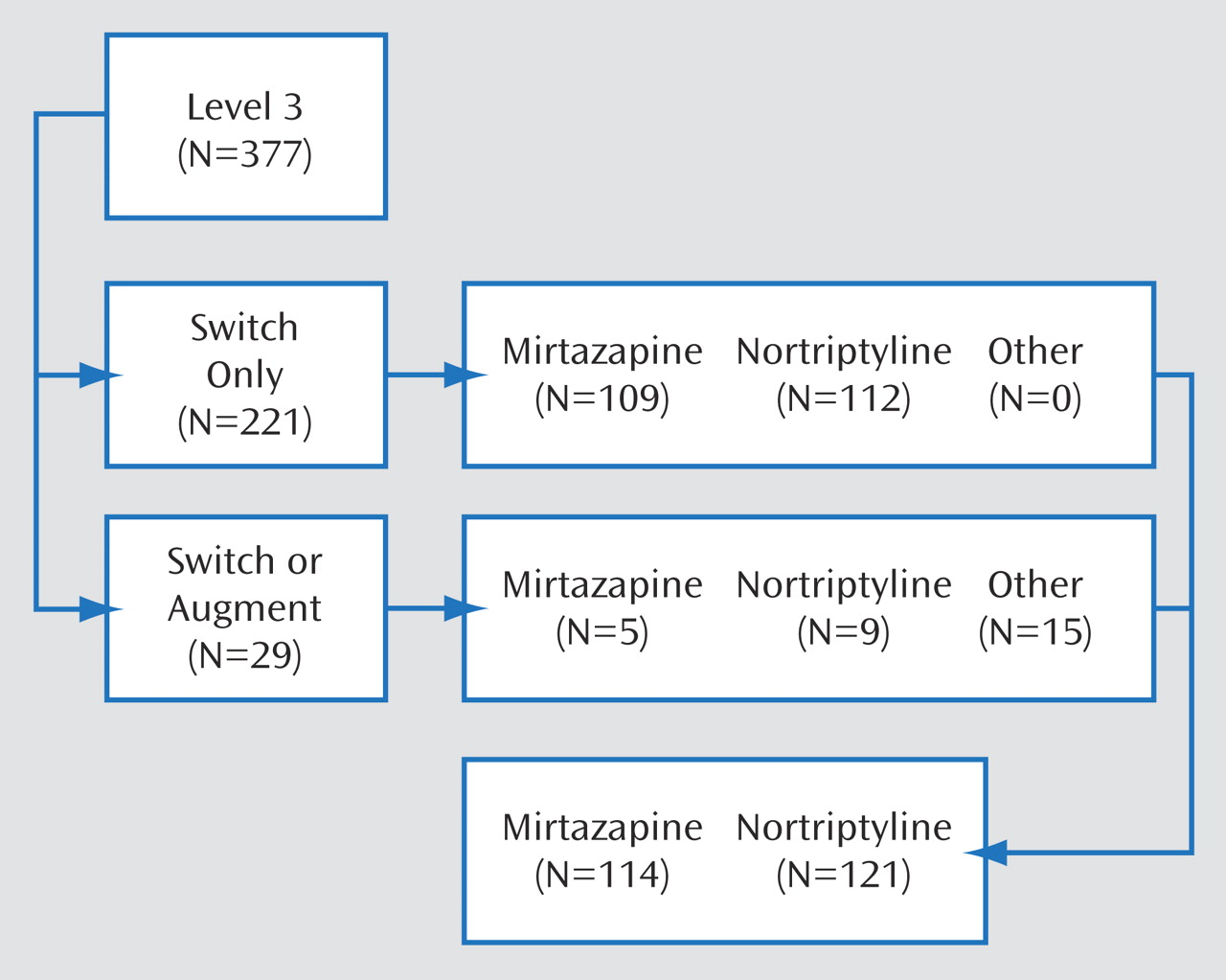

Level 3 compared the relative effectiveness of two antidepressant switch strategies (mirtazapine or nortriptyline) and two augmentation options (lithium or T

3 thyroid hormone) using the equipoise stratified randomized design

(12) . This report presents the main outcomes that compared the two Level 3 switch strategies (mirtazapine versus nortriptyline) to which participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio, stratified by acceptability to subjects and regional center.

Protocol Treatment

To mimic clinical practice, enhance safety, and ensure vigorous dosing, participants and treating clinicians were not masked to either treatment assignment or dose. A clinical treatment manual (www.star-d.org) recommended starting doses and dose changes for each medication guided by both symptom ratings (per the QIDS-C

16 [

15,

16 ]) and side effect ratings (per the Frequency, Intensity, and Burden of Side Effects Rating

[12] ) obtained at each treatment visit. Furthermore, didactic instruction, clinical research coordinator support, and a centralized monitoring system

(20) with feedback constituted intense efforts to assure timely dose increases when inadequate symptom reduction occurred in the context of acceptable side effects. Clinical management aimed to achieve symptom remission (operationally defined for clinic personnel as a QIDS-C

16 score ≤5 at exit from the treatment). The protocol recommended medication clinic visits at weeks 0, 2, 4, 6, 9, and 12, but visit schedules were flexible (e.g., the week 2 visit could occur acceptably within 6 days of week 2). Extra visits could be scheduled if needed, and for a participant who showed a response or remission only at week 12, two additional visits were permitted to determine whether that status was sustained.

At participant entry into this Level 3 switch trial, citalopram, along with the Level 2 augmenting agents bupropion and buspirone, were discontinued without tapering at the initial Level 3 treatment visit, as were the Level 2 and 2A monotherapy regimens (bupropion, sertraline, and venlafaxine). Either mirtazapine or nortriptyline was begun without a washout period. Recommended mirtazapine doses were 15 mg/day for the first 7 days, 30 mg/day by day 8, 45 mg/day by day 28, and, if necessary, 60 mg/day by day 42. Recommended nortriptyline doses were 25 mg/day for 3 days, 50 mg/day for 4 days, and then 75 mg/day by day 8, 100 mg/day by day 28, and, if necessary, 150 mg/day by day 42. These dosing recommendations were flexible, based on clinical judgment informed by the side effect and the QIDS-C 16 ratings obtained at each treatment visit, and guided by the clinical manual (www.star-d.org). Clinicians were allowed (but not required) to use measurements of nortriptyline blood levels to guide dosing decisions. During the course of the study, nortriptyline blood levels were obtained in 33.9% of the participants; the mean nortriptyline blood level was 91.66 ng/ml (SD=86.03).

Concomitant Treatments

Stimulant, anticonvulsant, antipsychotic, mood stabilizing, nonprotocol antidepressant medications, and potential antidepressant augmenting agents (e.g., buspirone) were proscribed. Otherwise, any concomitant medication was allowed to manage concurrent general medical conditions or protocol antidepressant side effects (e.g., sexual dysfunction), as were anxiolytics (except alprazolam) and sedative hypnotics (including trazodone, ≤200 mg h.s., for sleep).

Measures

Clinical and demographic features were defined at baseline study entry before Level 1 treatment

(4) . Baseline measures included the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale

(21) to assess general medical conditions, the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire

(22,

23) to assess comorbid psychiatric disorders, and the 30-item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Clinician-Rated

(24) completed by both the clinical research coordinator and the research outcomes assessor to assess depression severity and selected symptom features. Assessments of overall functioning (Short-Form Health Survey

[25], Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire

[26], Work and Social Adjustment Scale

[27] ) and satisfaction (Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire

[28] ) were collected by an automated interactive voice response telephone system

(29 –

31) .

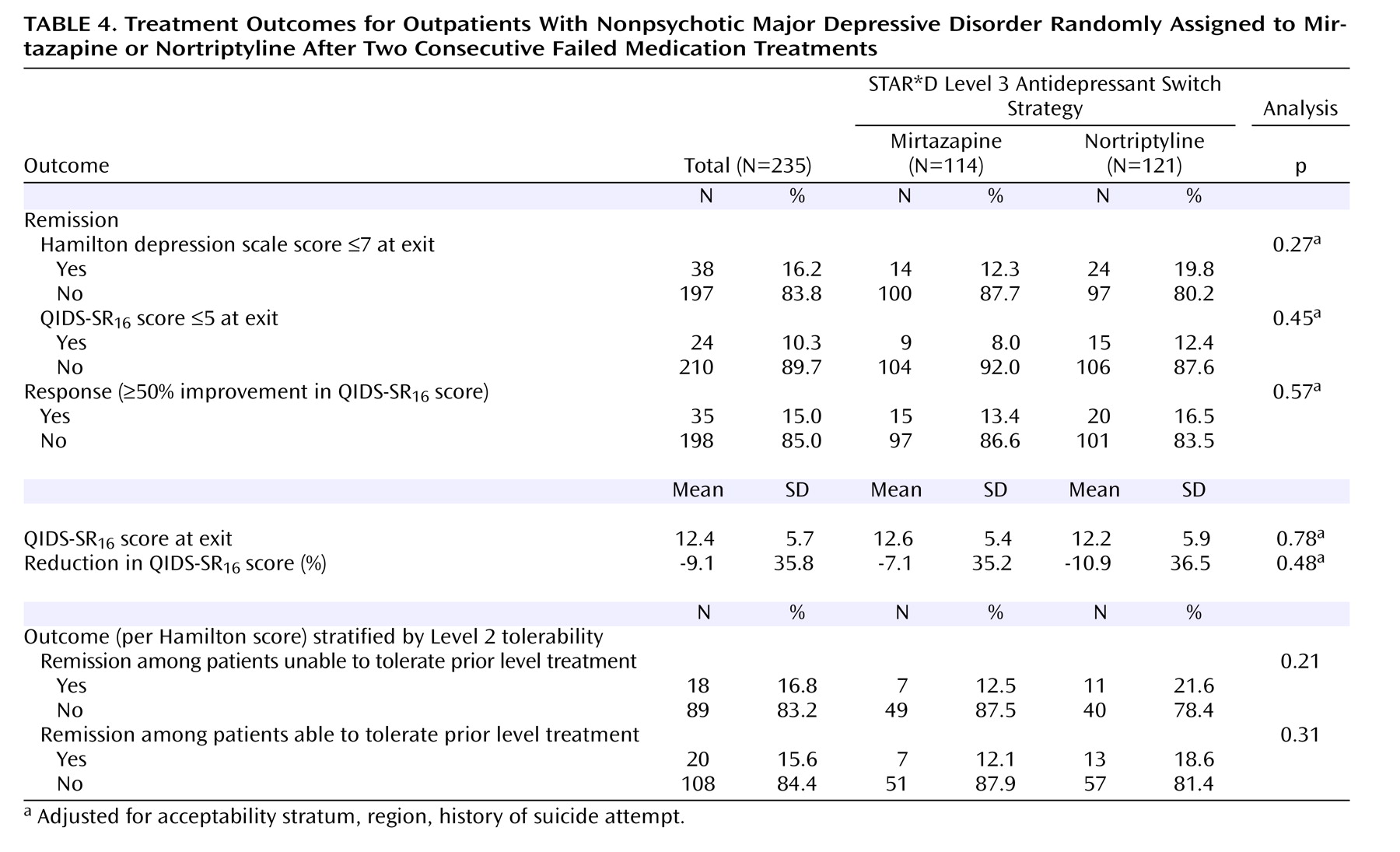

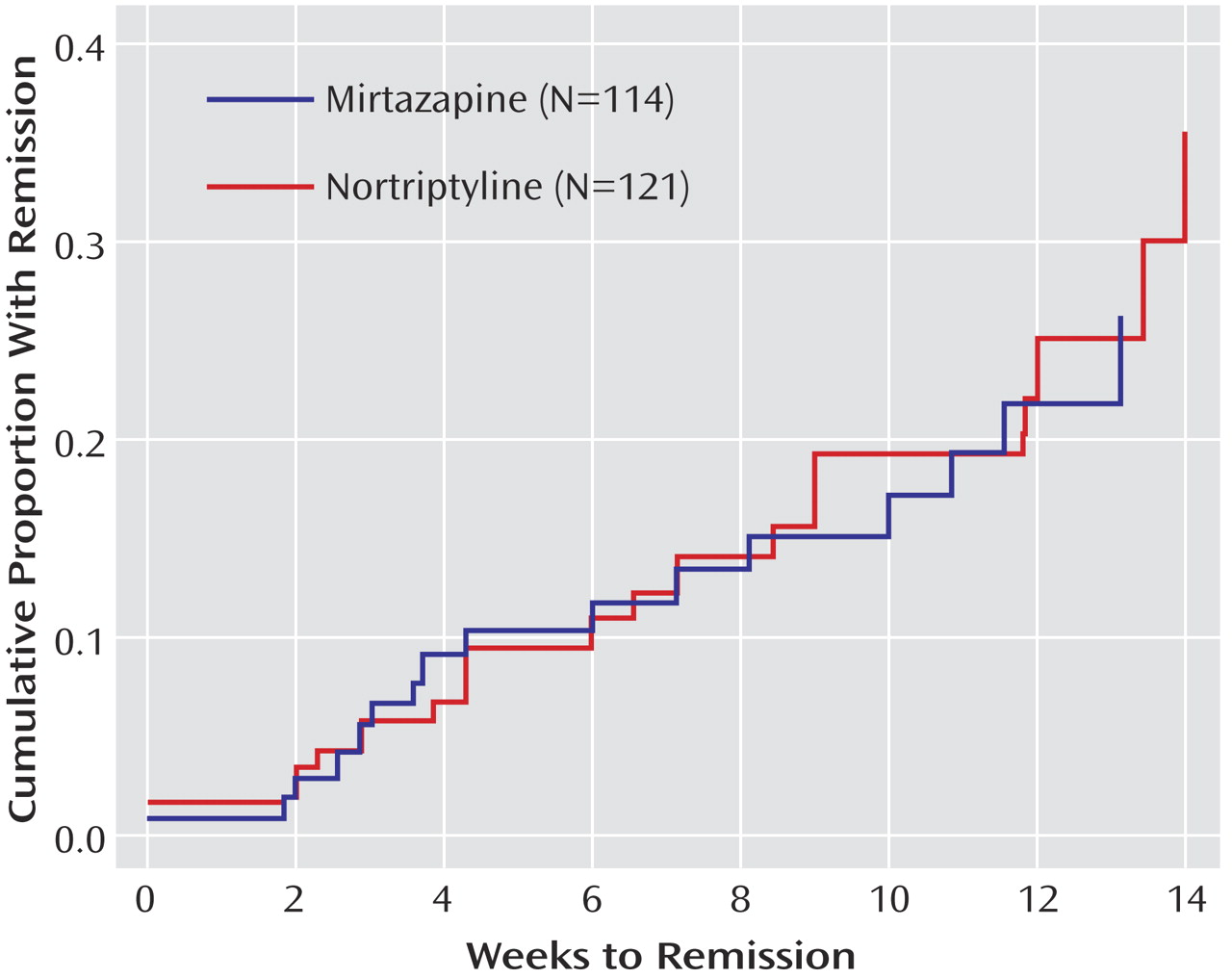

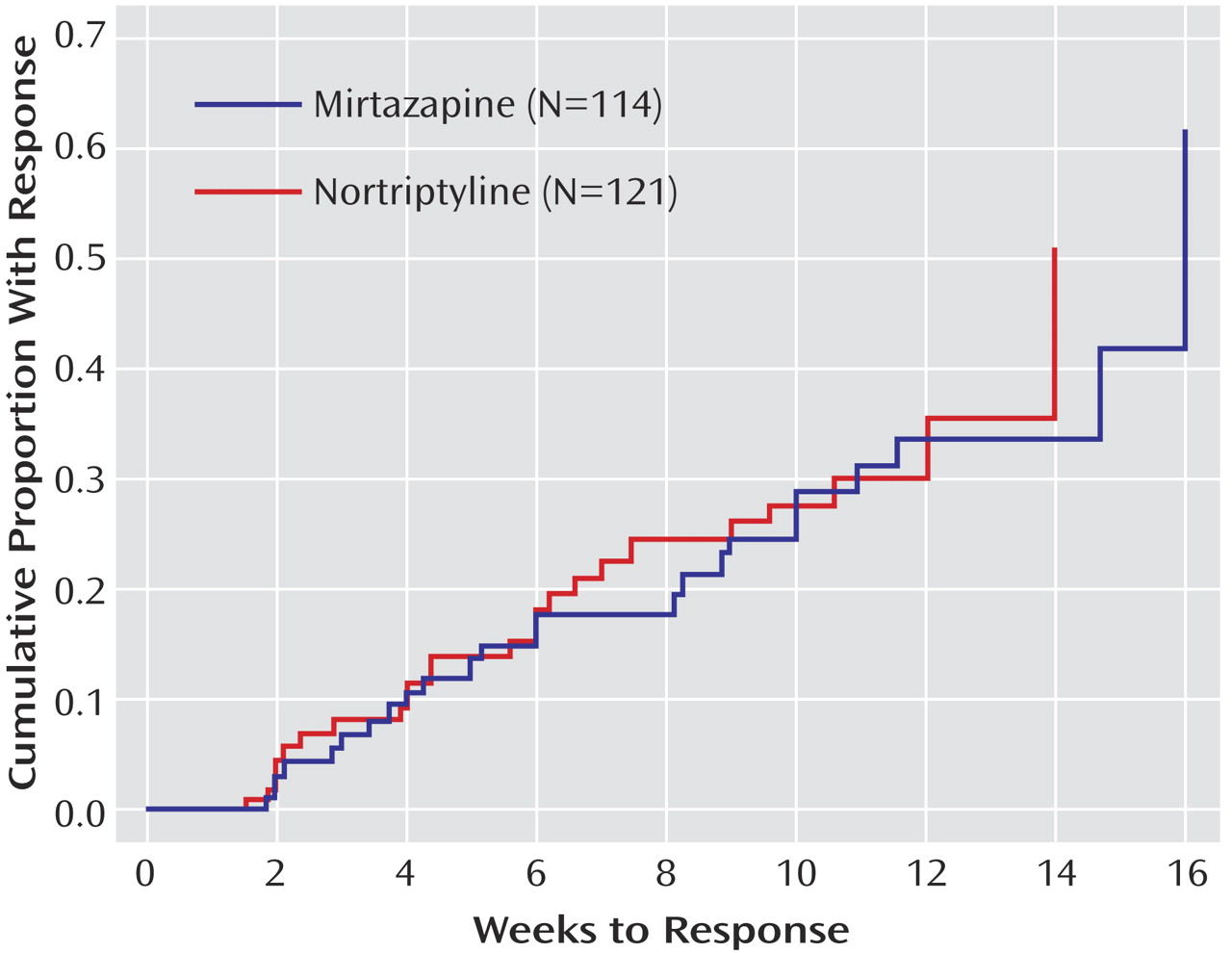

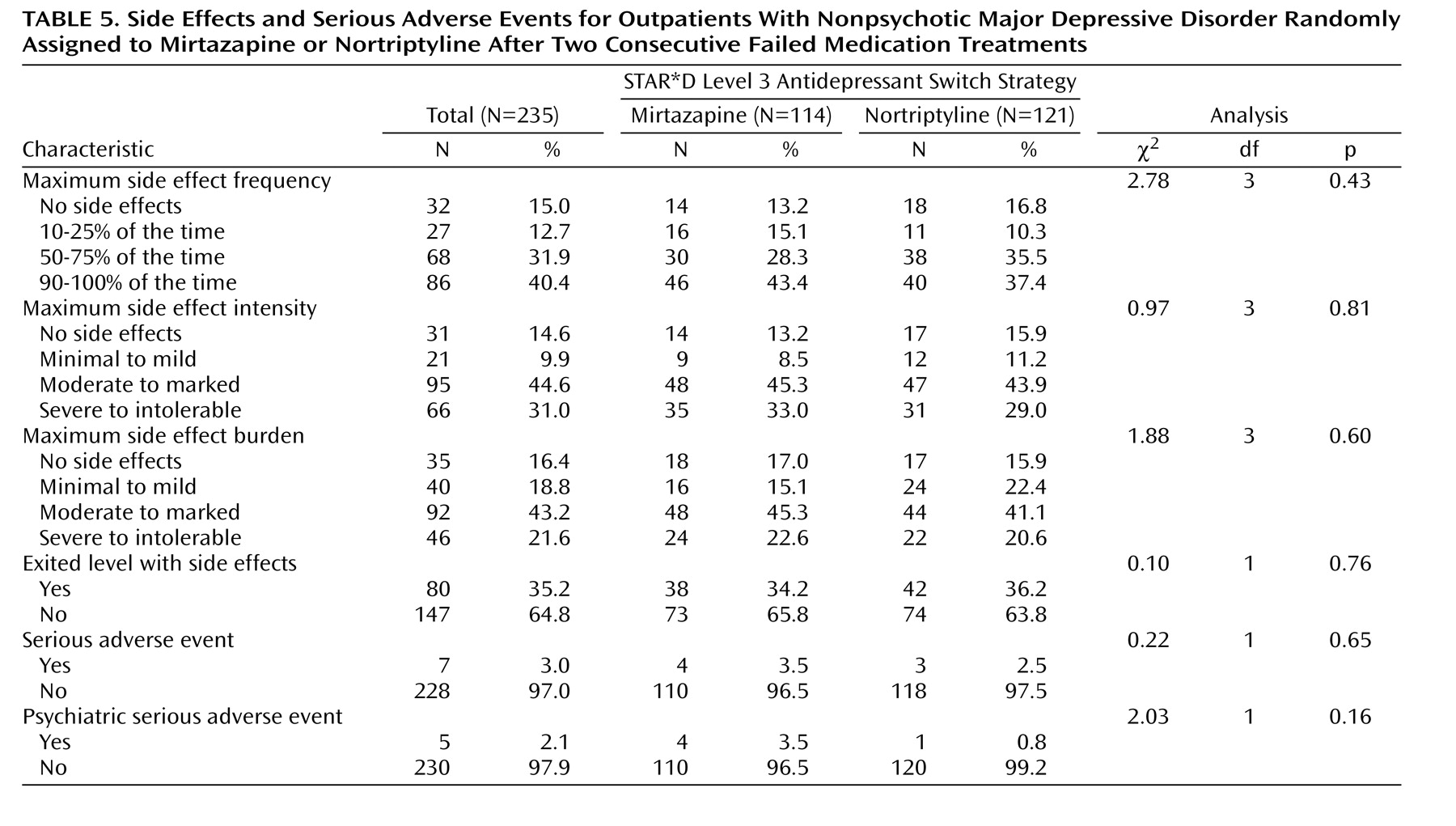

The primary outcome, symptom remission, was defined as a total score ≤7 on the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression obtained via telephone-based structured interviews (English or Spanish) conducted by independent, treatment-masked research outcomes assessors within 5 days of entry and exit from this study. The Hamilton depression scale items of psychomotor retardation and agitation were evaluated by the research outcomes assessors on the basis of study participant self-report. The intraclass correlation coefficient for Hamilton depression scale administered via telephone by research outcomes assessors and in person by the clinical research coordinators was 0.66 (N=3,876). In addition, research outcomes assessors participated in numerous training sessions throughout the conduct of the study to prevent rater drift and to ensure a consistent approach to symptom assessment. Secondary outcomes included QIDS-SR 6 scores and side effect ratings obtained at each treatment visit. For QIDS-SR 16 scores, remission was defined as a total score ≤5 at Level 3 exit, while response was a reduction of ≥50% from the Level 3 baseline score.

Statistical Methods

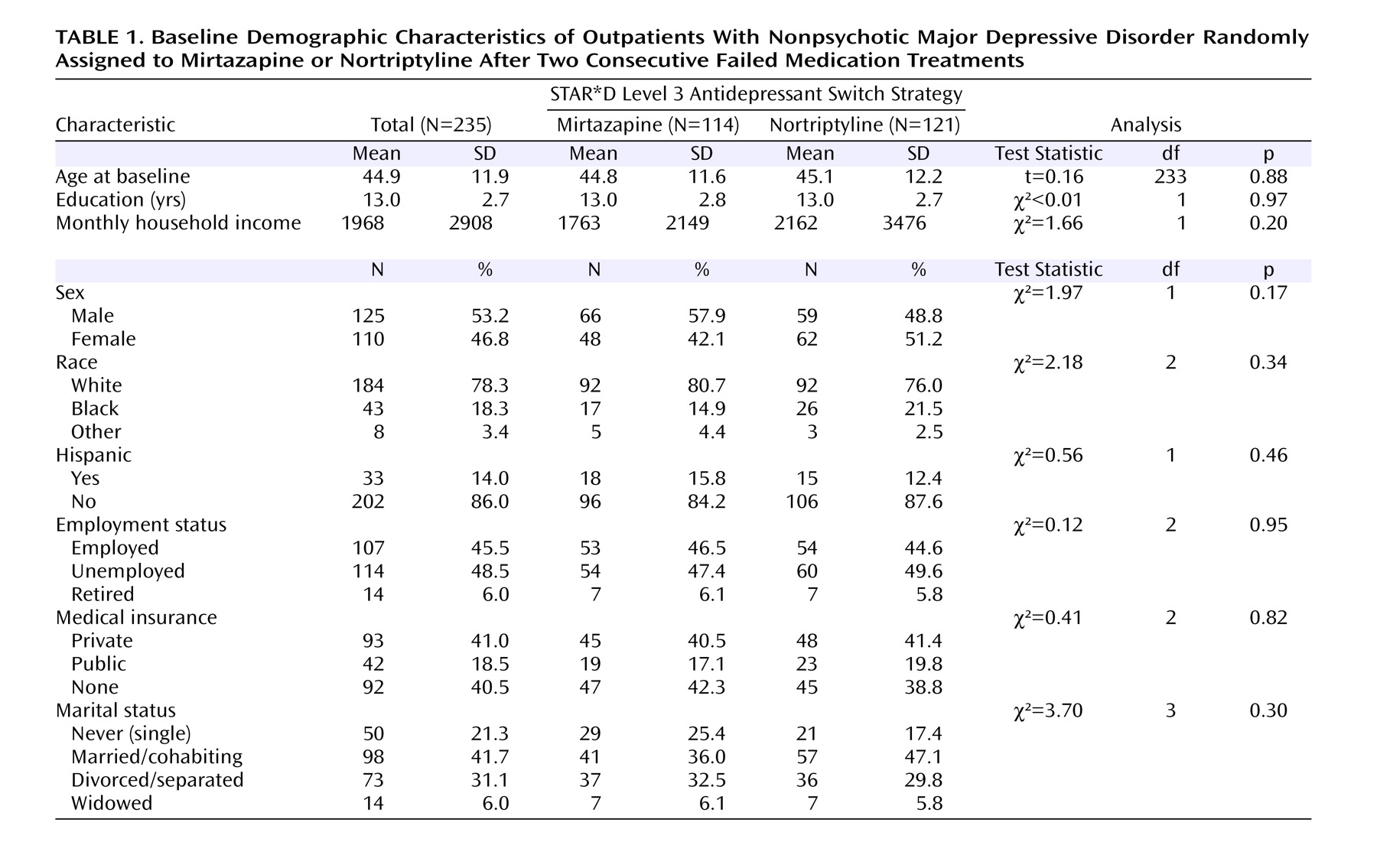

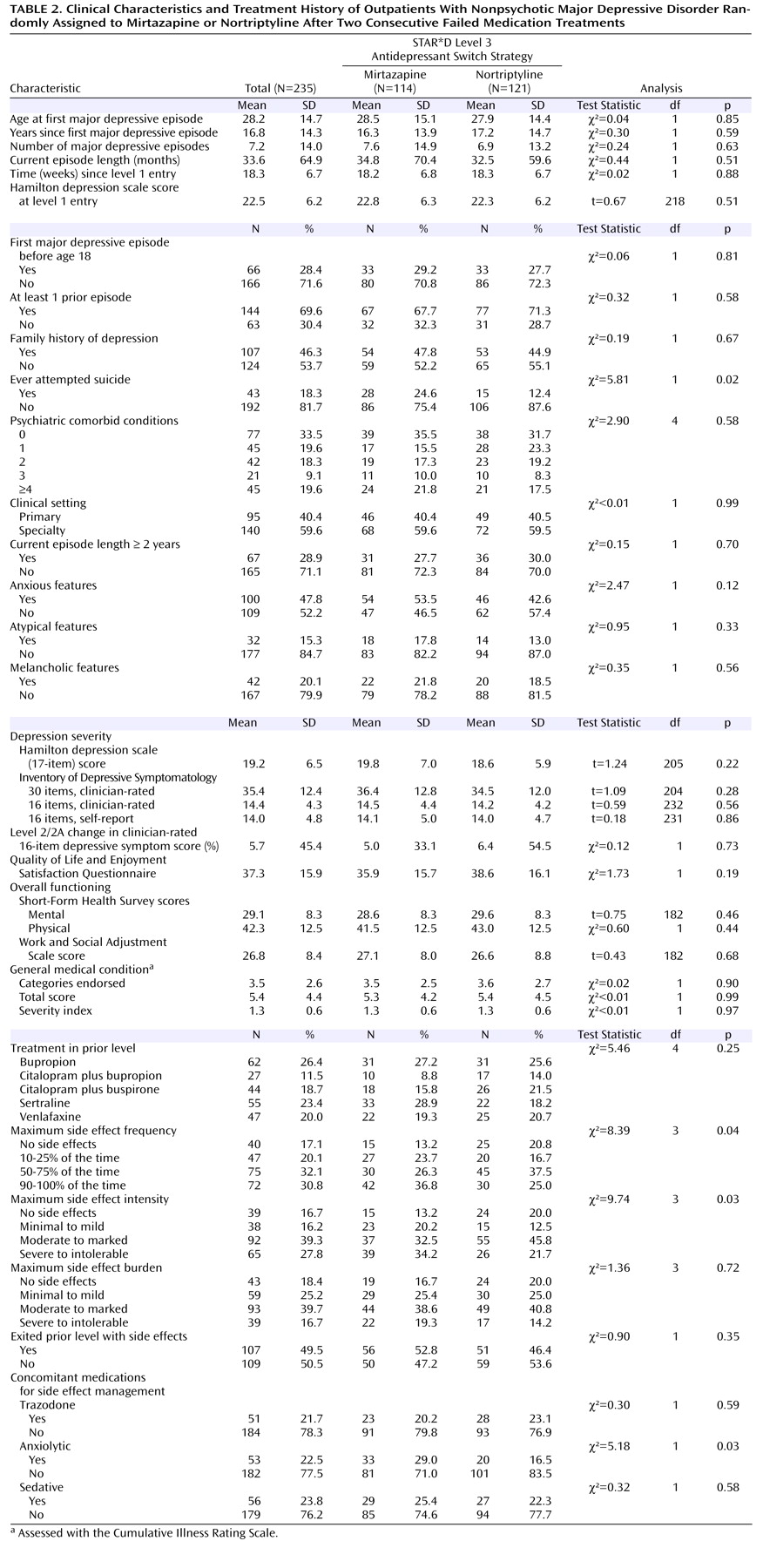

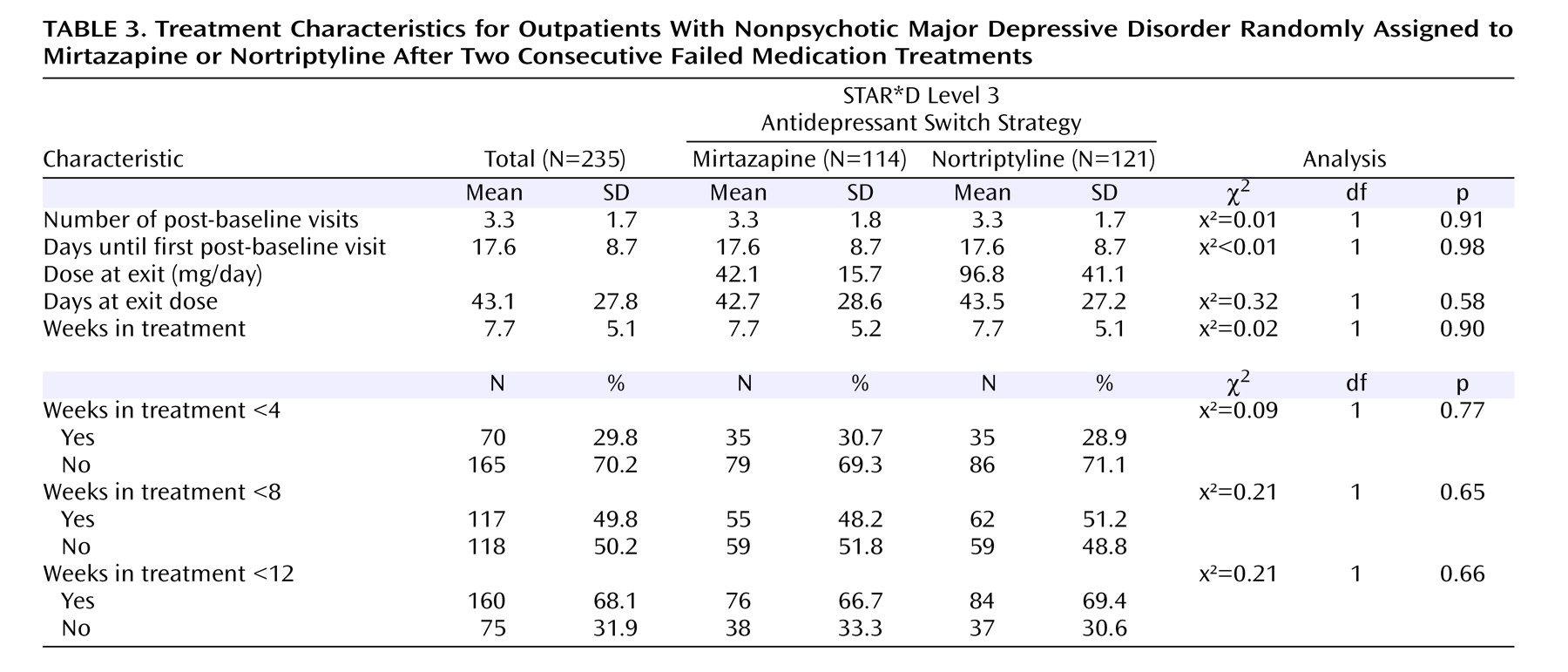

Student’s t tests, Wilcoxon tests, and chi-square tests were used to compare the baseline clinical and demographic features, treatment features, side effects, and serious adverse event rates across treatments and for the entire cohort.

All analyses were conducted using all participants randomly assigned to each treatment group

(13) . Remission was defined as Hamilton depression scale total score ≤7 (per masked rater assessment) and QIDS-SR

16 score ≤5 (obtained at each treatment visit). The remission threshold for the self-reported depressive symptom inventory score was established using item response theory analysis and was chosen because it corresponds to a score of 7 or less on the Hamilton depression scale

(15) . Logistic regression models were used to compare the remission and response rates after adjusting for the effect of regional center, the two acceptability strata, and baseline clinical and demographic factors that were not balanced across treatment groups (history of prior suicide attempt was the only such factor identified). Times to first remission (QIDS-SR

16 score ≤5) and first response (≥50% reduction from baseline) were defined as the first observed point using clinic visit data. Log-rank tests were used to compare the cumulative proportion with remission and response across the two treatment groups. Additional exploratory logistic regression analyses were conducted to determine if there was a differential effect of treatment among those who were unable to tolerate their prior medication treatment.

When outcome Hamilton depression scale scores were missing, participants were assumed to not have achieved remission (as defined in the original proposal

[12] ). Sensitivity analyses were conducted to determine if the method of addressing the missing data had an impact on the results of the study. An additional method of addressing the missing data, using an imputed value generated from an item response theory analysis of the relationship between the Hamilton depression scale and the QIDS-SR

16 score, was used in the analysis of remission based on the Hamilton depression scale.

DISCUSSION

We found no statistical difference in remission rates for participants treated with mirtazapine or nortriptyline as a third-step medication strategy after inadequate response or intolerance to two previous medication treatments for depression. Remission rates (as assessed by the Hamilton depression scale and QIDS-SR 16 ) were 12.3% and 8.0%, respectively, for mirtazapine and 19.8% and 12.4% for nortriptyline. In addition, the two antidepressants did not differ in tolerability or adverse events. No treatment group differences could be identified for response rates (per QIDS-SR 16 scores), time to response or remission, serious adverse events, or side effects. A relatively small proportion of study participants continued their Level 3 treatment longer than 12 weeks, as one would expect in an effectiveness trial with “real world” populations.

The modest remission rates (less than 20%) achieved in this trial were not likely due to either medication underdosing or to inadequate treatment durations for either medication, given the vigorous dosing schedule and diligent implementation of the protocol. As described earlier, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate the methods used to address the missing Hamilton depression scale data. Both the multiple imputation approach, and the use of values imputed from the QIDS-C

16 scores at exit based on item response theory

(15) revealed remarkably similar findings, indicating that the analyses were not sensitive to the missing data methodology. In addition, no differential treatment effects were found after we controlled for the imbalance across the two groups of those unable to tolerate their Level 2/2A treatment. Secondary analyses using Hamilton depression scale remission rates did not identify a differential treatment effect among those who were and were not intolerant to Level 2/2A treatment.

From a pharmacological standpoint, serotonin reuptake inhibition was the primary pharmacological action of citalopram, the Level 1 treatment, and most of the Level 2/2A treatments (i.e., those involving either a switch to sertraline or citalopram augmentation). Two of the Level 2 switch strategies did not selectively affect the serotonergic neurotransmission system: sustained-release bupropion is a norepinephrine/dopamine reuptake inhibitor, and extended-release venlafaxine is a serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. It is noteworthy that the two Level 3 switch strategies involved agents with pharmacological actions different from those of previous levels. Mirtazapine, an antagonist of presynaptic alpha 2-adrenergic autoreceptors and heteroreceptors on both the norepinephrine and serotonin neurons, is also a potent antagonist of postsynaptic serotonin 5-HT

2 and 5-HT

3 receptors

(32) and is an inhibitor of the release of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) from CRH-containing neurons

(33) . On the other hand, nortriptyline, a secondary-amine tricyclic antidepressant, strongly inhibits the norepinephrine transporter

(34) . It also significantly antagonizes serotonin 5-HT

2 receptors (in particular, 5-HT

2C receptors

[35] ) and modestly inhibits GABA transporters

(36), with only mild inhibition of the serotonin transporter

(34) . The outcomes observed with these two Level 3 switch agents, despite their distinctive pharmacological actions compared with the primary reuptake inhibition of Level 1 and 2 medications, suggest that there is no clear advantage in switching to either one of these two treatments for outpatients who have not responded to multiple treatment trials and that the use of successive monotherapies results in only modest remission rates, even when the antidepressants have pharmacological profiles that clearly differ from those of the previous agents. While some depression treatment guidelines suggest the utility of three sequential monotherapies

(37), these results suggest that this approach yields rather limited results.

This study indicates that fewer than one in five depressed patients may achieve remission upon switching to another antidepressant medication after two unsuccessful medication treatments. Contrary to previous efficacy trials in major depressive disorder with 27%–50% remission rates upon switching to other antidepressants in patients who had not benefited adequately from two antidepressant trials

(6,

8), this effectiveness study suggests that switching antidepressants, as a third-step treatment for such patients, provides rather modest chances of remission. Rates reported in previous open-label switch efficacy studies following two antidepressant treatments often involved the recruitment of subjects with nonchronic depression and minimal concurrent general medical comorbidity and whose treatment resistance was, in most cases, not prospectively determined. Our findings, in contrast, are generalizable to most adult outpatients with nonpsychotic major depressive disorder treated in real-world, primary or specialty care settings, although perhaps enriched with uninsured (40.5%) and unemployed (48.5%) populations.

Study limitations include the lack of a placebo control condition and nonmasked treatment delivery, although assessors of the primary outcome (Hamilton depression scale) were masked to treatment, and the QIDS-SR 16 score and the Hamilton depression scale ratings were in agreement. While a placebo control condition could have helped to determine whether improvement was due to spontaneous improvement or to nonspecific aspects of treatment, such a control is not required to discern whether these two treatments differed. Further, switching to a placebo after two consecutive failed treatment trials would have raised insurmountable human participant concerns and likely would have limited generalizability if many participants refused random assignment. A blinded placebo control condition could also have led to less vigorous dosing, given the high prevalence of multiple general medical conditions in our participants.

One might raise the issue that the failure to achieve remission in the prior level despite significant improvement could have yielded relatively high rates of remission in Level 3 with only modest reductions in depressive symptoms. However, since patients had the option of choosing to be randomly assigned only to augmentation strategies at Level 3, one may assume that those study participants who had improved significantly in the previous level would be less likely to accept switching treatments as an option. This is also suggested by the fairly significant level of depression severity at the time of entry into Level 3 (mean Hamilton depression scale score of 19.2) for those who agreed to be randomly assigned to a medication switch. Another limitation relates to the fact that participants were immediately switched to nortriptyline or mirtazapine. It is possible that discontinuation-emergent adverse events may have occurred and may have limited some participants’ ability to tolerate such a switch. On the other hand, there was no significant difference in exit rates between the two treatments during the first 2 weeks of the study. In addition, a previous open trial demonstrated the feasibility and safety of an abrupt switch from SSRIs to mirtazapine, without significant immediate dropouts

(9) .

One might argue that a relative limitation of our study is its overall size, and that our study was not powered to detect a difference of 10% or more in remission rates, assuming the lowest remission rate was 12.3%, since a 10% difference in an adequately powered study would have required the random assignment of over 480 patients. However, our study was the largest ever (N=235) among investigations of depressed patients having completed two consecutive failed antidepressant trials. In addition, a difference of at least 15% between the two treatments was identified as the minimum clinically meaningful difference. Therefore, with this cohort, there was adequate power (at least 80%) to detect a 15% difference, if the lowest remission rate was 12.3%, and we can conclude that, based on our assumptions, neither treatment was significantly more effective than the other.

Finally, one may argue that defining remission as the primary outcome of the study may fail to distinguish between those who achieve remission with very small percentage changes in depressive symptoms (as in the case of those partial responders who entered Level 3) and those who achieve it with greater than 50% reductions in overall symptoms. On the other hand, the 8.0% and 12.3% remission rates with mirtazapine and nortriptyline per QIDS-SR 16 scores are comparable to the 7.1% and 10.9% mean percentage reductions in QIDS-SR 16 scores observed with these two treatments, suggesting that results based on remission are comparable to more traditional approaches that focus on changes in symptom severity.