The current optimal treatment for hepatitis C virus consists of pegylated interferon (IFN), given via injection once per week, and daily doses of ribavirin

(3) . Antiviral treatment for hepatitis C virus is either for 24 or 48 weeks, depending on the genotype of the virus. Response to treatment is measured by determining viral titers of hepatitis C viral RNA. An end-of-treatment response is defined as the absence of hepatitis C virus viral RNA immediately after the course of treatment is completed. A sustained viral response is the absence of hepatitis C viral RNA 6 months after treatment is completed. Patients with a sustained viral response have a more than 95% chance of remaining virus free indefinitely. Treatment for hepatitis C virus can pose mental health challenges because antiviral therapy can induce depressive symptoms and has occasionally been known to trigger mania or psychoses

(4,

5) . Antiviral therapy may also exacerbate preexisting mental health conditions, including depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and mania. Antiviral therapy has also been associated with the relapse of substance use

(6) . It is generally recommended that patients with preexisting mental health or substance dependence conditions be stable at least 6 months before initiation of antiviral therapy

(7) .

Addiction psychiatrists are familiar with the phenomenon of patients receiving opioid substitution experimenting with trials of discontinuation of treatment. There may be a variety of events that trigger such experimentation. General psychiatrists and others should be aware that successful completion of treatment of hepatitis C virus may be a time of increased risk and, as in this case, may result in a relapse to heroin use. After discussing the high-intensity treatment that this patient received to successfully eradicate his hepatitis C virus, we discuss our team’s approach to the patient’s relapse to heroin use and some of the barriers that we faced in attempting to address that problem. Furthermore, the literature focuses mainly on supporting the patient through the trial of IFN treatment, a period considered high risk for the emergence of psychiatric symptoms and substance abuse relapse. The stressors that patients may experience with both successful and unsuccessful antiviral treatment are generally not addressed, and these stressors definitely contributed to our patient’s ultimate relapse to the use of heroin.

Discussion

The decision to start giving antiviral therapy to a patient with a history of opioid dependence should take into account the risks and benefits for the patient. For some patients, antiviral therapy may be absolutely contraindicated, including those with acute suicidal ideation, severe personality disorders, ongoing heavy alcohol use, dementia, or other cognitive problems that might impair treatment compliance or safety. For those who have been actively using opioids, many authors recommend that the patient have 6 months of documented abstinence, although some studies have suggested that it may be possible to successfully treat patients with shorter periods of abstinence or even ongoing drug use

(10) .

High-risk patients benefit from an integrated treatment model that allows for input and monitoring from multiple medical and mental health providers, as was available to Mr. O. They also benefit from increased support during antiviral therapy. This support can come from a variety of sources. Family members, friends, neighbors, and employers can all be helpful. As described, clinical interventions can include more frequent visits to mental health, medical, or methadone clinics

(12) .

Patients receiving methadone maintenance treatment may experience increased cravings while receiving antiviral therapy because the side effects may mimic opioid withdrawal symptoms. Craving may also be secondary to mood changes caused by antiviral therapy or be cue-related to needles that are used to deliver INF. There has been research to suggest that INF does not alter the pharmacokinetics of methadone in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus who are undergoing methadone maintenance therapy

(13) . However, an increase in methadone dose may be necessary to decrease drug cravings during IFN treatment, as was illustrated by Mr. O. Typically, this dose increase is only 5–10 mg/day and can be tapered after antiviral therapy

(14) . In this case, the weekly visits for shots to the liver clinic helped to decrease the cue-related cravings and provided ongoing support and monitoring of the patient’s health status. Sertraline was eventually reinstated to treat what was either a relapse of the depression associated with schizoaffective disorder or antiviral-induced dysphoria. Several studies have shown that antidepressants can be useful in managing mood changes secondary to antiviral therapy (e.g., reference

15 ).

Patients who have a history of opioid dependence who are not receiving methadone maintenance treatment may also seek antiviral therapy for hepatitis C virus. In one study comparing 50 people with a history of intravenous drug use receiving methadone maintenance treatment to 50 who were not receiving such treatment (matched for genotype), it was found that the group receiving methadone maintenance treatment had a statistically better end-of-treatment response to antiviral therapy, but there was no statistical difference in the sustained viral response between the two groups. This suggests that some people with a history of intravenous drug use who are not receiving opioid-replacement therapy may also be candidates for antiviral therapy, particularly if they are expected to be highly treatment compliant. However, 12 of those who were not maintained with methadone treatment relapsed to intravenous drug use, whereas none of those taking methadone did so. This suggests that those with opioid dependence who were not receiving opioid-substitution treatment may need even closer clinical monitoring or should perhaps be considered for opioid-substitution therapy before starting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C virus

(7) .

If a patient relapses to the use of street drugs, appropriate harm-reduction interventions should occur until the patient is able or willing to engage more actively in treatment, as illustrated by our patient. There are several harm-reduction techniques that may be effective for heroin users, including education about safe injection practices and psychosocial interventions. Ideally the patient will be able to integrate harm-reduction skills early in treatment so that he or she will have the necessary knowledge to apply when at risk for relapse.

Mr. O relapsed after completion of antiviral treatment, so the question of whether to continue antiviral treatment after relapse to opioids was not an issue. Studies have shown that those who relapse while taking intravenous drugs and receiving treatment are likely to maintain a sustained viral response as long as they continue to keep regularly scheduled clinic appointments and take medications as prescribed. In contrast, alcohol use during antiviral therapy for hepatitis C virus may result in a decreased viral response, despite continuation of antiviral therapy

(16) . One 5-year follow-up study of 27 injection drug users who had cleared the hepatitis C virus showed that nine of them eventually relapsed to intravenous drug use, but only one of those became reinfected

(17) . Similar results have been found by other researchers

(18 –

20) . These data suggest that even if patients who have been treated for hepatitis C virus do relapse into intravenous drug use, education regarding safe injection practices can prevent reinfection with hepatitis C virus.

Although our clinic does not require a treatment contract with every person treated with antiviral therapy, some higher-risk patients are asked to sign one. Treatment contracts can include such contingencies as taking medication for mental health conditions, meeting with a therapist or mental health practitioner as appropriate, increasing the frequency of mental health or medical appointments, documenting attendance at a certain number of Alcoholics Anonymous or other sobriety meetings, and submitting to regular or random urine drug screening tests. Such requirements are not meant to be punitive but to allow the clinic to provide antiviral therapy in the safest manner possible.

Mr. O had schizoaffective disorder, and we suspected that he may have experienced increased psychotic symptoms while taking IFN. The cause of psychosis may include the physical and psychological stress of IFN treatment or complex drug interactions resulting in decreased levels of antipsychotic medication. Initially, Mr. O was taking three drugs that are metabolized by the CYP P450 1A2 system: caffeine, four cups per day; nicotine, 40 cigarettes per day; and olanzapine, 20 mg/day. Because of the caffeine and cigarettes, he likely had enzyme induction of the P450 1A2 liver isoenzyme, resulting in as much as 40% lower blood levels of olanzapine

(21) . Several studies have suggested that IFN may down-regulate the entire P450 system

(22) . This may have resulted in decreased drug metabolism in Mr. O and resulted in potentially higher levels of olanzapine. Although increased olanzapine levels might have been therapeutic, it is conceivable that the patient’s blood levels of caffeine and nicotine may have also been increased. This may have increased his irritability and potentially his paranoia.

As shown with Mr. O, completion of antiviral therapy and successful clearance of the hepatitis C virus do not mean that patients are no longer in need of close psychiatric follow-up. Mr. O felt that after antiviral therapy, he could continue toward a healthier lifestyle by no longer taking psychiatric or opioid-replacement medications. Patients should be encouraged to carefully consider major decisions about discontinuing medications or other major health-related changes after completing antiviral therapy. Patients may benefit from psychotherapeutic interventions throughout treatment to discuss what it has meant to have hepatitis C virus, their feelings about the behaviors that contributed to hepatitis C virus infection, coping with the side effects of antiviral therapy and related changes in their quality of life, and what life might be like after either clearing the virus or potentially failing to clear it.

This case also exemplifies the need for higher-intensity follow-up in those with opioid dependence. While receiving antiviral therapy, these patients are closely monitored for changes in physical and mental health and are frequently highly motivated to succeed at their goal of completing treatment and becoming negative for the hepatitis C virus. In this instance, the patient had at least weekly contact with a provider during treatment. Successful completion of antiviral therapy resulted in a reduction in the number of clinic visits. This patient and others may benefit from continued frequent clinical contacts until other life activities are substituted.

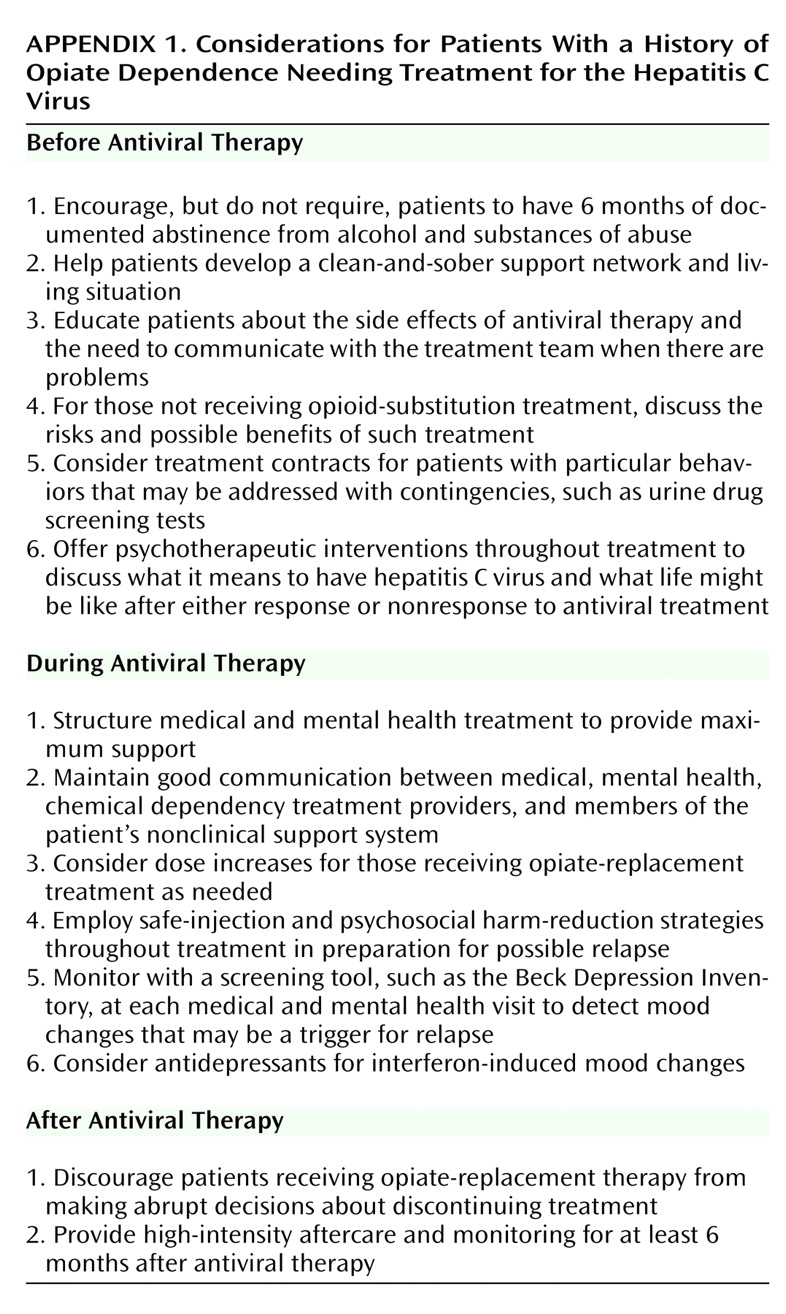

As described, patients with a history of opioid dependence and/or chronic mental illness have unique issues when they are being considered for IFN treatment (

Appendix 1 ). Further research that examines the safety and efficacy of antiviral therapy for hepatitis C virus in those with a history of opioid dependence is warranted. Specialized treatment models for these patients may optimize treatment outcomes. Prospective controlled trials are needed to compare those receiving methadone maintenance treatment with those who are not. To date, we are aware of no studies that examine patients taking buprenorphine and compare their treatment outcomes to those taking methadone or those not taking opioid-replacement medications.

There may also be a period after antiviral therapy in which a patient is more vulnerable to relapse to opioids. It would be useful to know the typical duration of this higher-risk period and the types of continuing-care practices that would be most beneficial. Patients are supported and encouraged while receiving antiviral therapy and may miss this support after successful treatment. Higher-intensity monitoring for at least 6 months after antiviral therapy and psychotherapeutic interventions throughout treatment addressing their thoughts and feelings about hepatitis C virus and antiviral therapy may be useful.