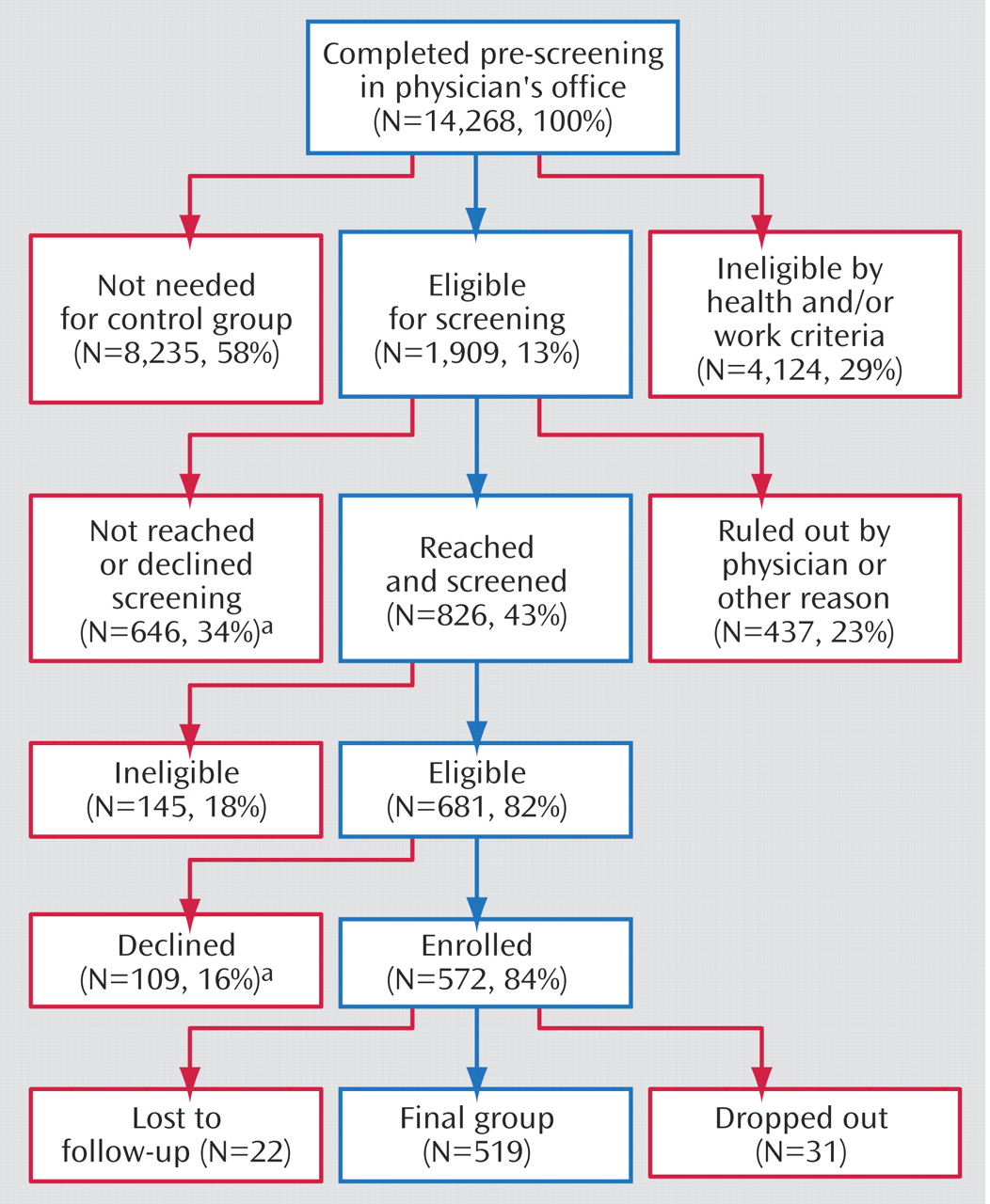

A total of 14,268 patients completed the prescreener questionnaire, and 1,909 (13%) were eligible for further screening (

Figure 1 ). Of these, 646 (34%) declined to participate in the screening or had inaccurate contact information (supplied by the primary care physician’s office), 437 (23%) were ineligible based on physician reports, and 826 (43%) were fully screened. Of these, 681 (82%) were confirmed eligible and 145 (18%) were ineligible. Of the 681 confirmed eligible patients, 109 (16%) declined to participate, and 572 (84%) enrolled (depression group=286, rheumatoid arthritis group=93, control group=193). Most follow-up administrations were completed (1,454 of 1,716 or 84.7%). The attrition rate was 9%.

There were no statistically significant differences between enrolled patients and patients who declined to participate with regard to prescreener employment status, Mental and Physical Component Summary scores, number of dysthymia or major depressive disorder symptoms, or comorbid diagnoses (p>0.05). The latter group was younger (39.0 versus 41.5 years; F=7.33, df=1, 604, p<0.01) and contained more men than women (38% versus 21%, F=21.33, df=1, 607, p<0.01).

Baseline Characteristics

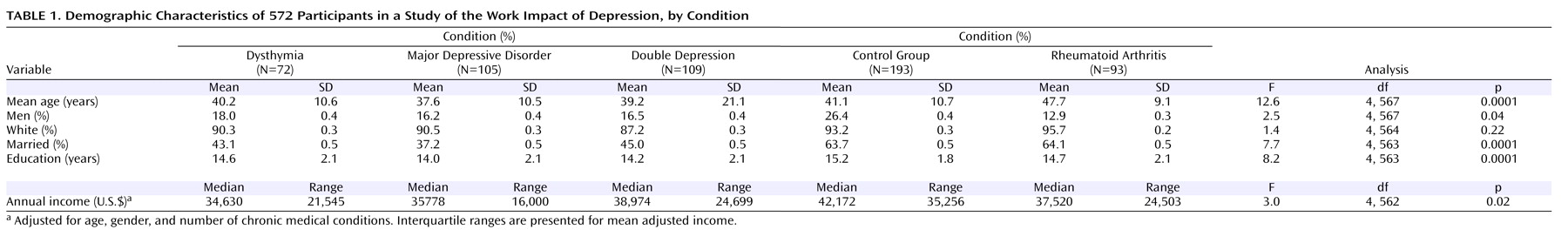

Of the 572 enrolled participants, 81% were women (N=461); 92% were white (N=521); 51% held professional, technical, and managerial occupations (N=292); 42% were in sales, support, and service occupations (N=237); and 7% were in production, construction, repairs, and transportation occupations (N=40). (Data not shown and were missing for three participants) (

Table 1 ). Mean weekly work hours were 38.6 (SD=–0.5). Few participants (N=40, 9.3%) were self-employed.

When we compared the combined depression group versus the control subjects versus the rheumatoid arthritis group, there were differences in age (F=23.7, df=2, 569, p<0.0001), marital status (F=14.7, df=2, 565, p<0.0001), education (F=14.2, df=2, 565, p<0.0001), and annual median income (F=3.2, df=2, 564, p=0.04). The depression group (

Table 1 ) was youngest, included fewer married individuals, was less educated, earned less, and held more jobs since age 18 (7.0 versus 5.9 versus 6.1).

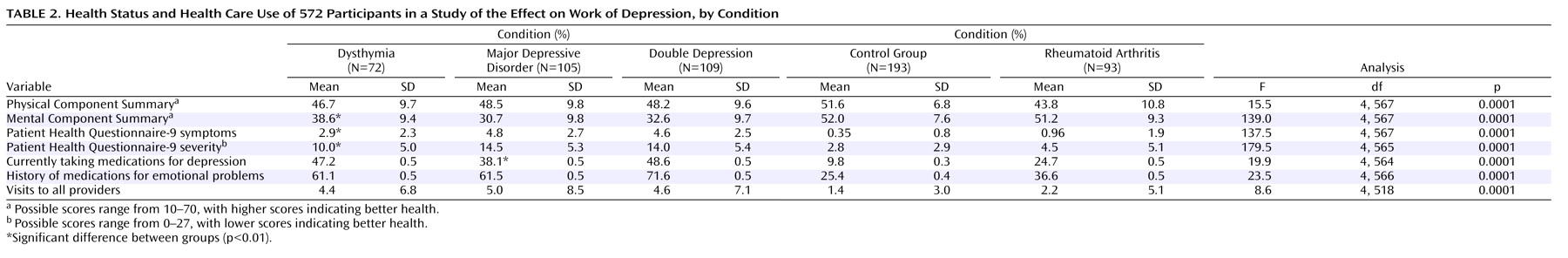

The three groups differed on Mental Component Summary 12 (F=318.0, df=2, 569, p<0.0001) and Physical Component Summary 12 scores (F=30.3, df=2, 569, p<0.0001), with the depressed group having the poorest health and with regard to the number of visits for emotional problems (F=17.1, df=2, 520, p<0.0001). The depression group had three times as many health care visits. Few patients reported that their primary care physicians had ever asked about work issues (dysthymia, 28%; major depressive disorder, 32%; double depression, 23%; rheumatoid arthritis, 26%, versus control subjects, 10%; F=6.4, df=4, 559, p<0.0001), or advised them to change their work (20%/19%/17%/20% versus 7%; F=3.5, df=4, 560, p=0.008).

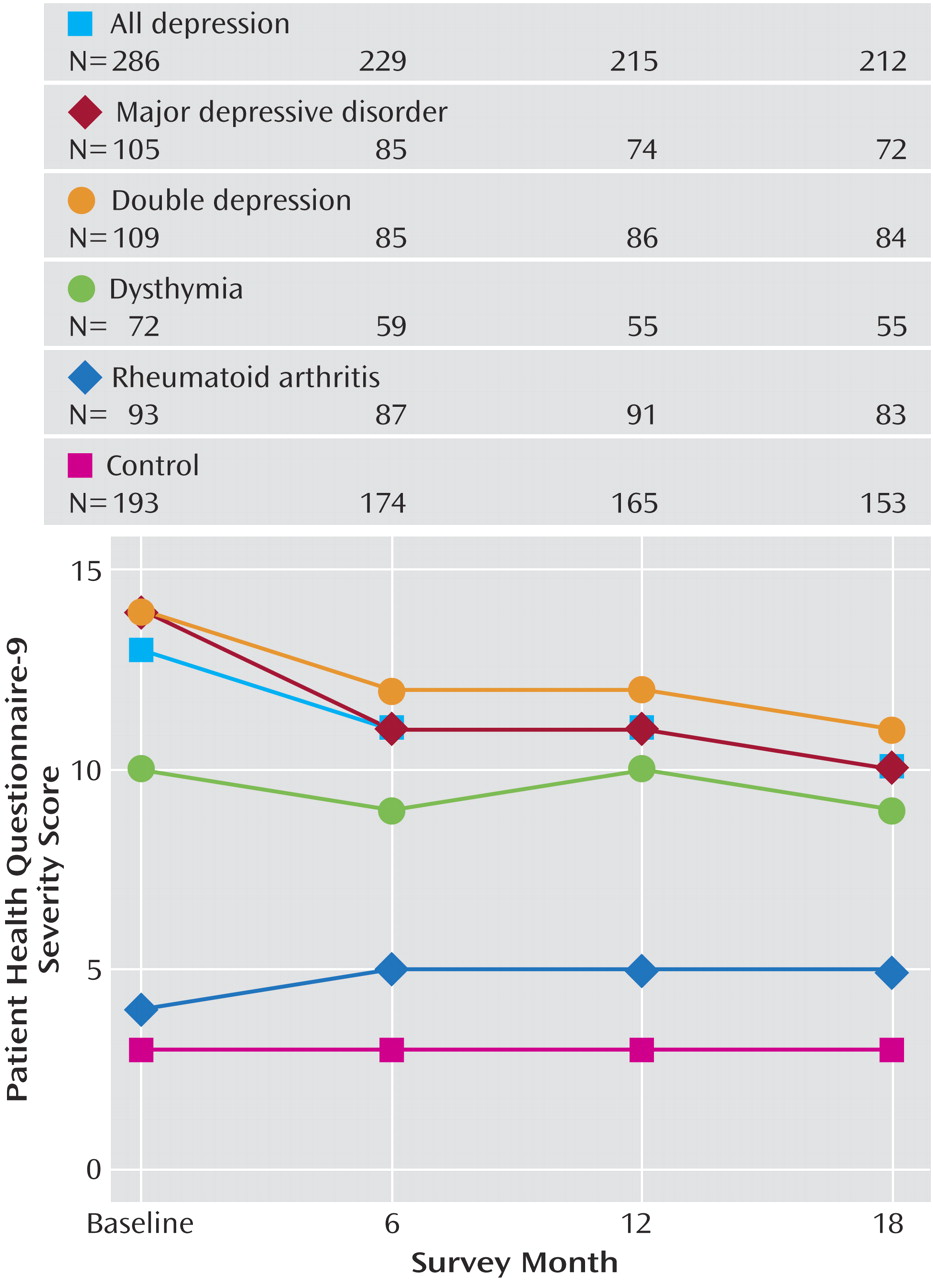

Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Depression Severity

In cross-sectional pairwise comparisons of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 depression severity scores, the combined depression group was worse than the control group: baseline difference (F=606.6, df=1, 569, p<0.0001); 6 month difference (F=262.3, df=1, 569, p<0.0001); 12-month difference (F=233.3, df=1, 569, p<0.0001); and 18-month difference (F=167.2, df=1, 569, p<0.0001). Cross-sectional comparisons contrasting the depression and rheumatoid arthritis groups demonstrated significant differences in Patient Health Questionnaire-9 severity scores (F=169.0, df=1, 569, p<0.0001); 6-month difference (F=73.9, df=1, 569, p<0.0001); 12-month difference (F=109.8, df=1, 569, p<0.0001); and 18-month difference (F=67.5, df=1, 569, p<0.0001) (

Figure 2 ).

Between baseline and 6-month follow-up, the combined depression group experienced a significant decline in severity (F=7.7, df=1, 569, p<0.01). Severity declined further between the 6-month and 18-month follow-up (F=4.2, df=1, 569, p=0.02). Between baseline and 6 months, 17% of the depression group (N=48, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 severity: mean=3.9) was clinically improved, 61% (N=176, Patient Health Questionnaire: mean=11.2) was the same, and 22% (N=62, Patient Health Questionnaire-9=18.4) worsened. By 18 months, of the 212 subjects with completed Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scores at all time points, 45 (21%) had remitted (0–1 symptoms).

Job Performance Deficits

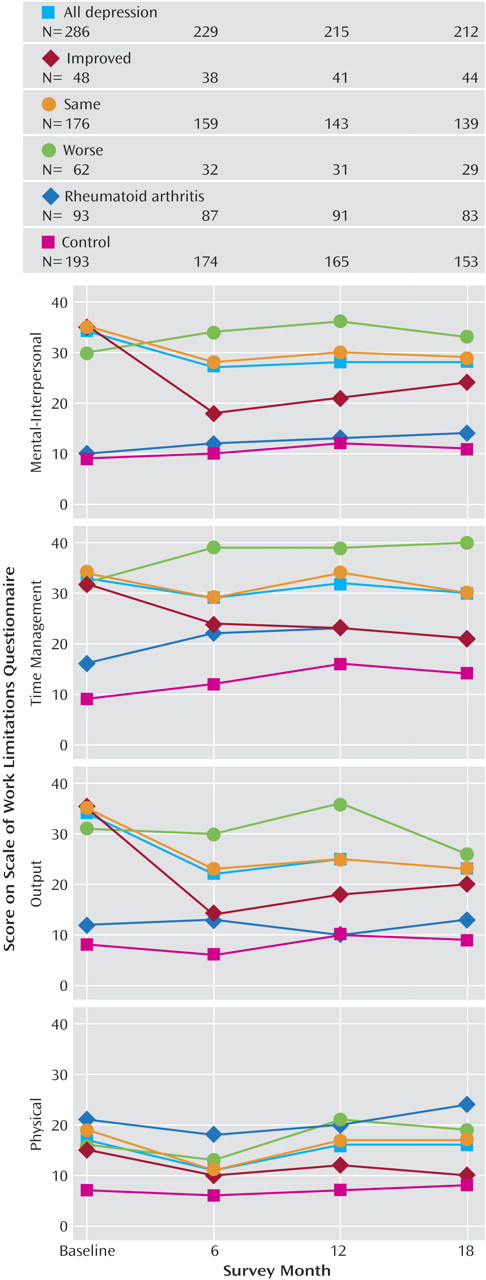

According to Work Limitations Questionnaire scores, the depression group had significantly greater job performance deficits at each time point than the control or the rheumatoid arthritis groups (

Figure 3 ). There were significant differences with regard to performing mental-interpersonal tasks (baseline: F=141.7; 6 months: F=39.0; 12 months: F=34.8; 18 months: F=39.0; all df=2, 560, p<0.0001), time management (baseline: F=94.7; 6 months: F=35.6; 12 months: F=23.4; 18 months: F=26.4, all df=2, 556, p<0.0001), output tasks (baseline: F=99.0; 6 months: F=27.7; 12 months: F=25.0; 18 months: F=20.9, all df=2, 558, p<0.0001), and physical tasks (baseline: F=25.4, 6 months: F=13.1; 12 months: F=18.5; 18 months: F=21.6, all df=2, 556, p<0.0001). In pairwise comparisons of the combined depression versus control groups, job performance was more impaired (mental-interpersonal baseline: F=238.5; 6 months: F=77.9; 12 months: F=65.6; 18 months: F=76.8; all=df 1, 560, p<0.0001; time management baseline: F=189.4; 6 months: F=62.9; 12 months: F=46.1; 18 months: F=51.1, all df=1, 556, p<0.0001; output baseline: F=194.8; 6 months: F=52.3; 12 months: F=45.0; 18 months: F=41.8, all df=1, 558, p<0.0001; and physical tasks baseline: F=17.5; 6 months: F=7.3; 12 months: F=19.6; 18 months: F=16.7, all df=1, 556, p<0.0001). However, in a pairwise comparison of the combined depression group and rheumatoid arthritis, performance of physical tasks was worse in the latter group at 6 and 18 months (6 months: F=6.8; 18 months: F=6.7, both df=1, 556, p=0.01; baseline: F=1.8; 12 months: F=1.7, both df=1, 556, p=0.20).

We assessed temporal changes in job performance among depression group subjects defined as clinically improved, the same, or worse. Between baseline and 6 months, job performance deficits declined significantly in the “clinically improved” group according to three of the four Work Limitations Questionnaire scales (mental-interpersonal: F=19.7, df=1, 560, p<0.0001; time: F=4.1, df=1, 556, p=0.04; output: F=21.3, df 1, 558, p<0.0001). Patients in the “same” severity group had significantly improved job performance (between baseline and 6 months) on each of the four Work Limitations Questionnaire scales (mental-interpersonal: F=11.6, df=1, 560, p<0.001; time management: F=5.0, df=1, 556, p=0.03; output: F=19.2, df=1, 558, p<0.0001; and physical: F=0.8.7, df=1, 556, p<0.01). Within this time period, patients in the “worse” severity subgroup had no significant changes in any scale scores.

Between the 6-month and 18-month follow-up intervals, job performance did not change significantly for any of the three severity depression groups, except in one instance. Deficits in performing physical job tasks increased significantly in the “same” severity group (F=4.3, df=1, 556, p=0.01) (

Figure 3 ).

Changes in depression severity and job performance were significantly positively correlated. For example, a 1.0-point decrease in depression severity was associated with a 1.2-point improvement in performing mental-interpersonal tasks (t=12, df=989, p<0.0001). However, comparisons of the combined depression group versus the control groups indicated that clinical improvement does not result in full recovery of job performance. Although the control group experienced an increase in deficits in performing mental-interpersonal tasks and time management, the job performance deficits even in the clinically improved group were greater at baseline and 18 months. These deficits affected performance of mental-interpersonal job tasks (baseline: F=77.4 and 18 months:: F=24.3, df=1, 560, p<0.001) and output tasks (baseline: F=51.6 and 18 months: F=6.9, df=1, 558, p<0.001).