The adverse consequences of depression are well established. Currently, of all illnesses, depressive disorder causes the largest amount of nonfatal burden, accounting for almost 12% of all years lived with disability worldwide

(1) . Depression is also associated with excess morbidity and mortality

(2), higher demands on caregivers and higher service use, and has substantial economical implications

(3) . In community-dwelling elderly people, the prevalence of depression requiring clinical attention is 13.5%

(4), and more than 50% have a chronic course

(5,

6) . Although effective treatment is available, case finding and adequate treatment in primary care are generally poor

(7,

8) . Still, even if all patients with depression were optimally treated with evidence-based interventions, only 34% of the disease burden in terms of years lived with disability could be averted

(9) . From the public health perspective, it is therefore of great interest to consider the possibility of depression prevention

(10,

11) . However, evidence-based preventive strategies aimed at reducing the incidence of late life depression in community living elderly people are sparse.

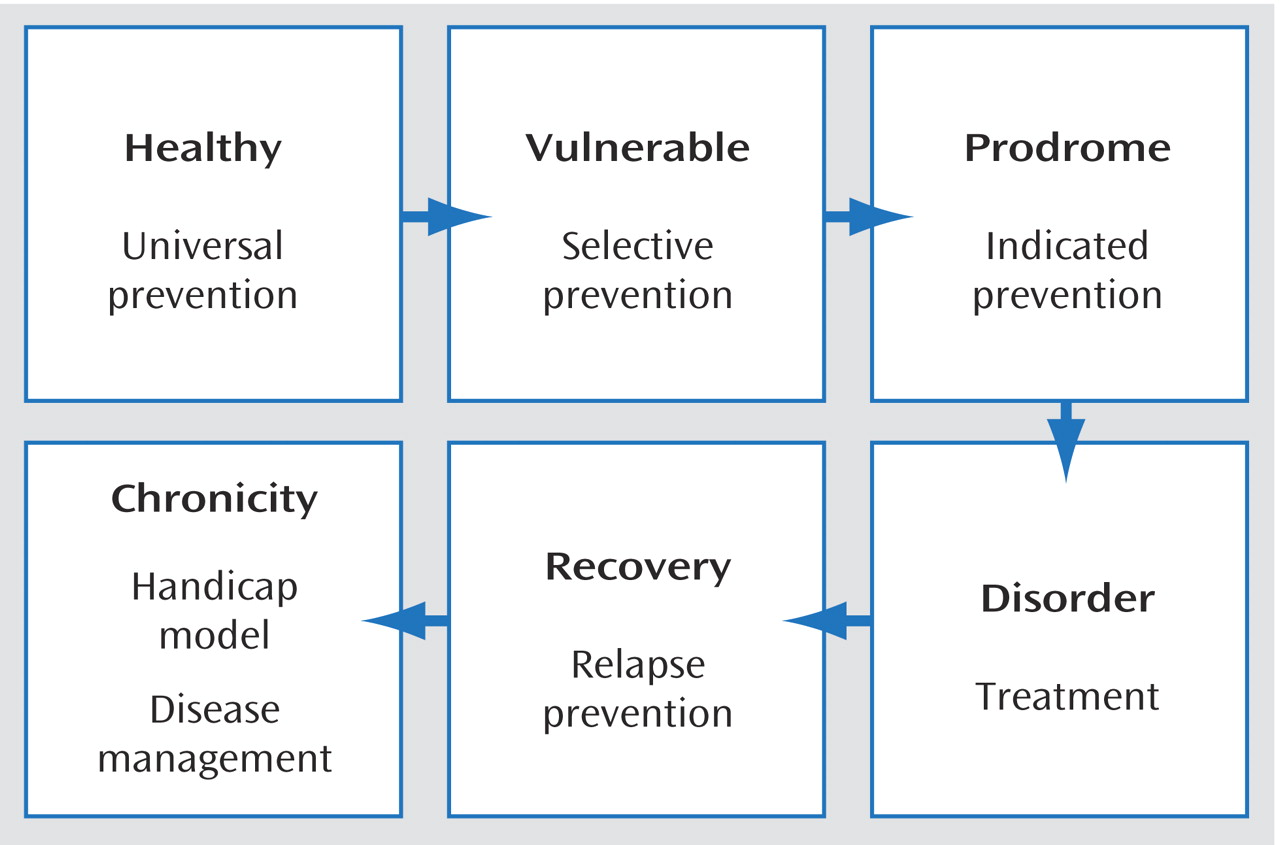

In prevention, different strategies can be chosen according to the stages or transitions in the development of a disorder

(12) (

Figure 1 ). Universal prevention aims to influence the behavior of the whole population to prevent the onset of disease. Examples of universal prevention are programs informing the population about the risk of alcohol intake or the benefits of physical exercise. Selective prevention is aimed at people who are at risk because they have been exposed to certain risk factors. In the case of depression, risk indicators are, for example, spousal loss and physical illness

(13) . The third form, indicated prevention, targets people who already have early or subsyndromal symptoms, in whom an intervention may reduce the likelihood of developing a full-blown case of depression

(12,

14) . An example of indicated prevention is cognitive therapy for the prevention of psychosis in people at ultrahigh risk

(15,

16) or pharmacotherapy for people with mild cognitive impairment to delay the onset of Alzheimer’s disease

(17) .

The choice for a specific type of prevention depends on the “untreated” prognosis of the disorder, in combination with the costs, benefits, and possible adverse consequences of different types of intervention. An ethical dilemma is that identifying a healthy person as a possible future case and starting some kind of intervention could carry certain negative consequences and should only be applied if the alternative has a significantly higher probability of adverse consequences. In the case of depression, evidence-based universal prevention of depression is currently nonexistent. Selective prevention may focus on people with certain risk indicators, such as exposure to loss. Indicated prevention would be directed at persons with depressive symptoms below the diagnostic threshold for “clinically relevant depression”

(18,

19) . For both ethical reasons and reasons of cost-effectiveness, preventative measures aimed at reducing the incidence of depression should target subjects with high a priori risk through exposure to multiple risk factors

(20) . Furthermore, for practical reasons, persons at risk should be easily identifiable in primary care, and risk profiles have to be simple and unambiguous. From a public health perspective, prevention should be cost-effective and lead to a substantial reduction of total disease burden. This implies that the selected risk indicators should be indicative of a substantial proportion of new cases.

Discussion

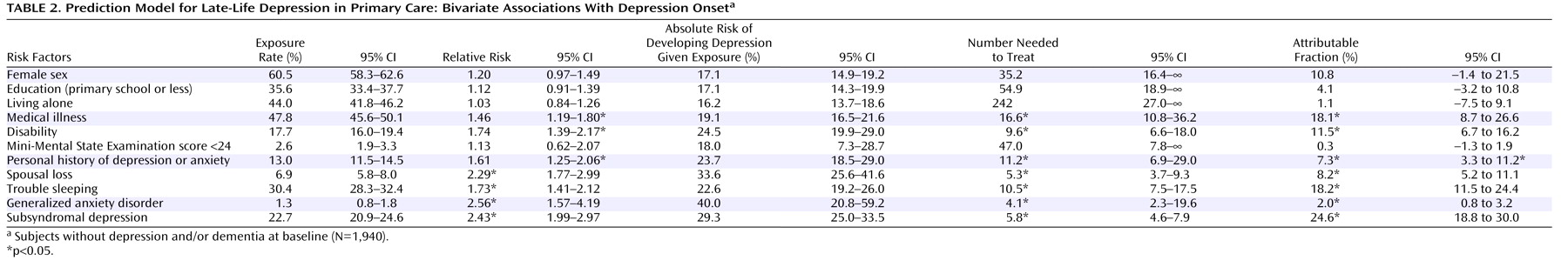

In this study, high-risk groups for incident depression were identified in a large cohort of elderly patients seen by general practitioners. Because case finding is generally poor, and both the prevalence and persistence of late-life depression are of major concern, the goal was to identify groups in primary care with a high vulnerability for depression according to easily identifiable criteria. Prevention is of interest, bearing in mind that even optimal care can only reduce the burden of depression by 34%

(9) . Because the detection of subsyndromal depressive symptoms requires more effort than recognizing other, more easily identifiable risk indicators in primary care, two models were compared that either incorporated or excluded subsyndromal depression as a predictor of the future onset of a full-blown depressive disorder. Thus, the potential health benefits of preventative measures aimed at reducing the incidence of late-life depression could be determined, taking into account the time that should be invested in adequate case finding in primary care. Although this approach, combining clinical, epidemiological, and public health perspectives has been strongly advocated

(14), it is relatively new to the field of common mental disorders.

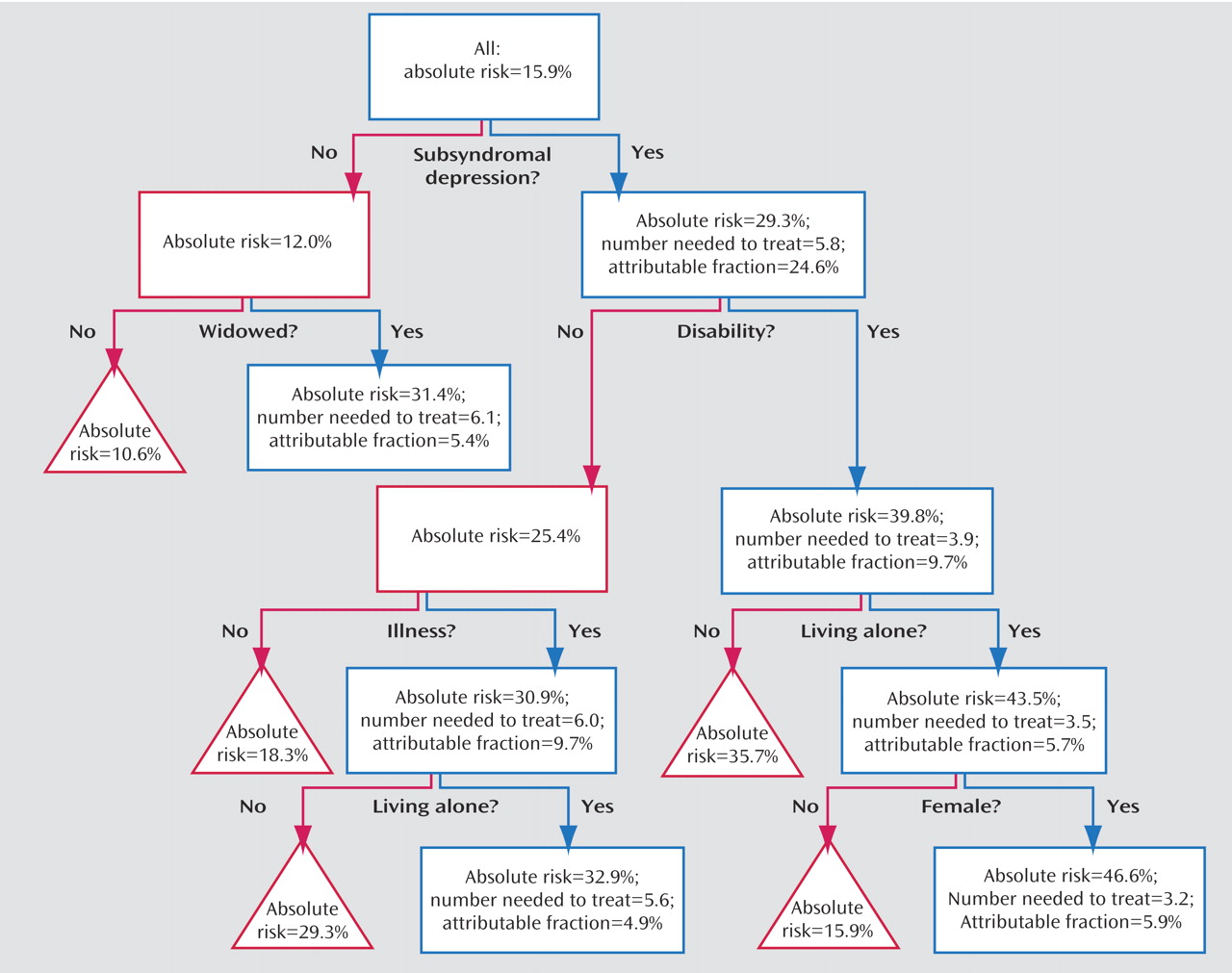

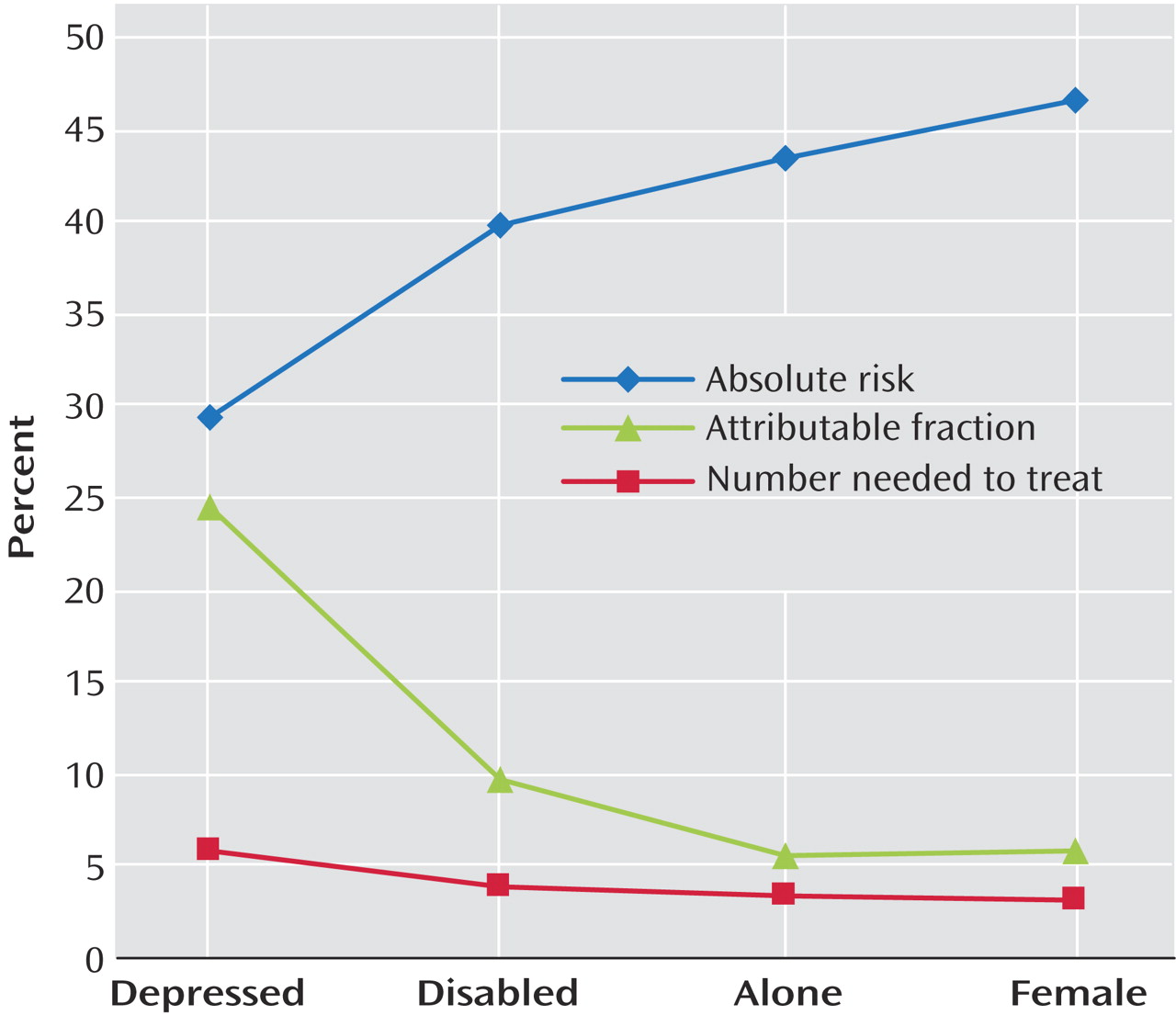

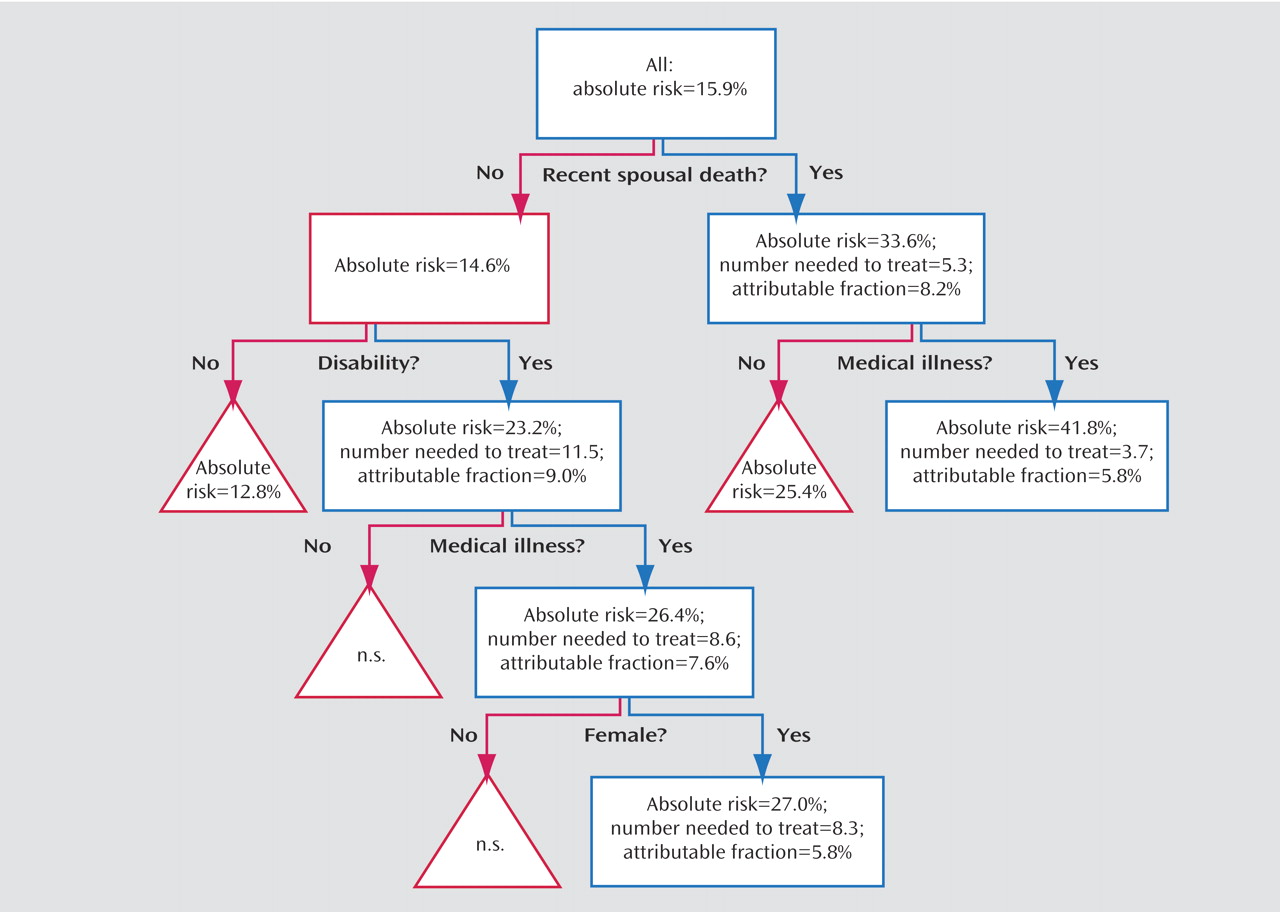

Our findings suggest that indicated prevention that involves identifying subsyndromal depressive symptoms as the most important risk indicator is the preferred option for identifying groups at high risk of developing depression. Subjects with depressive symptoms had a risk of almost 30% and accounted for 24.6% of the new cases at follow-up. With a number needed to treat of 5.8, which carries the promise of efficient interventions in this group, these subjects are of major interest for preventative interventions. Further subdivision of the sample according to combinations of risk factors yielded groups with an even higher risk of developing depression and lower numbers needed to treat, but these more narrowly focused approaches have a smaller impact on the incidence rate of depression in the population. For example, disabled women with subsyndromal symptoms who live alone had a 47% risk of becoming depressed, a number needed to treat of only 3.2 but a relatively low attributable fraction (5.9%), indicating that the incidence rate would only fall by 5.9% at best.

In a recent meta-analysis on short-term psychotherapeutic interventions aimed at people with subsyndromal depressive symptoms, these were found to reduce the incidence of depression by 30%

(38) . If this were applied to a sample such as ours, the number needed to treat for intervention would be 19.3 (5.8/0.3) for those with subsyndromal depression. For a relatively intensive form of treatment, this may be considered to be too great an effort, and it could be argued that one should start with those subjects who have the highest vulnerability. Further subdivision in the classification and regression tree analysis then leads to smaller subgroups that were exposed to more risk factors. In women with disability who live alone, the adjusted number needed to treat would be 10.7 (3.2/0.3). As an alternative to cognitive behavior therapy, less costly forms of indicated prevention should also be taken into consideration. Both bibliotherapy

(39) and the Coping With Depression course, a manualized form of self-help with instructions on mood management, were found to be effective therapies for unipolar depression, with effect sizes that are comparable to those of other treatment modalities for depression

(40) . Very recently, minimal contact psychotherapy along these lines has been proven effective in reducing the onset of depression in primary care patients with subthreshold depression

(41) . Also in low-cost computerized form, such interventions have proved effective

(42,

43) .

If one considers selective prevention of late-life depression, our analyses show that, in line with earlier findings

(44), elderly persons who recently lost their spouses are at great risk of developing depression, and even more if they also have a chronic medical condition (absolute risk=41.8%, number needed to treat=3.7). Overall, the attributable fractions in this model were somewhat smaller, which means that fewer cases can be prevented. Examples of preventative programs directed at persons who lost their spouses include self-help groups of fellow sufferers that convene for emotional exchange and support, specific courses on competences needed to cope with single life, and “widow-to-widow” programs in which women who had lost their husbands earlier visit recently widowed women for emotional and practical support. Although these programs have shown promising results in terms of postbereavement adaptation

(45) and social functioning

(46), the evidence of efficacy in reducing depression onset is limited. In a meta-analysis of eight types of such interventions, Cuijpers et al.

(47) found an effect size of 0.34 in relation to control subjects, but the number of published studies is still limited, and this difference was not statistically significant. When we consider the fact that these are low-cost community-based interventions, randomized controlled trials are urgently needed.

Indicated prevention thus has the best chance of detecting large groups of subjects at high risk of developing depression, with numbers needed to treat that could make preventative actions cost-effective by using available evidence-based interventions. Still, in comparison with selective prevention, indicated prevention requires the extra effort of screening subjects for subsyndromal depression. A number of screening instruments have been validated for case finding in community living elderly. These include the Center for Epidemologic Studies Depression Scale, a 30-item questionnaire on depressive symptoms

(4,

48,

49) but more recently also the 15-item version of the Geriatric Depression Scale

(50 –

53) has demonstrated its effectiveness for detecting elderly subjects with depressive symptoms in the community. The screening of large numbers of patients in primary care has been shown to be both feasible and effective

(54,

55) . Therefore, primary care facilities appear to be well equipped to find elderly persons with subsyndromal symptoms.

Strengths and Limitations

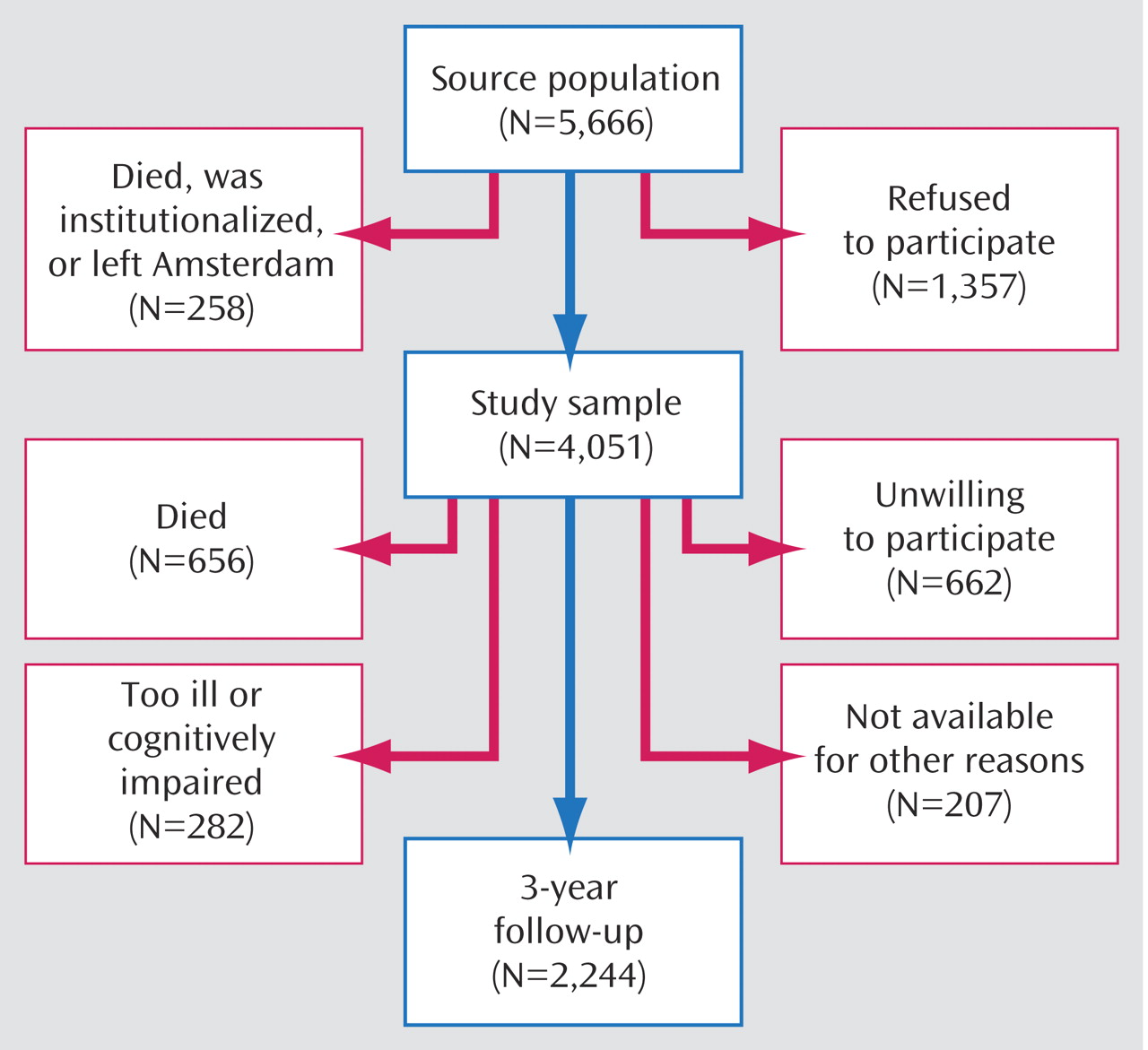

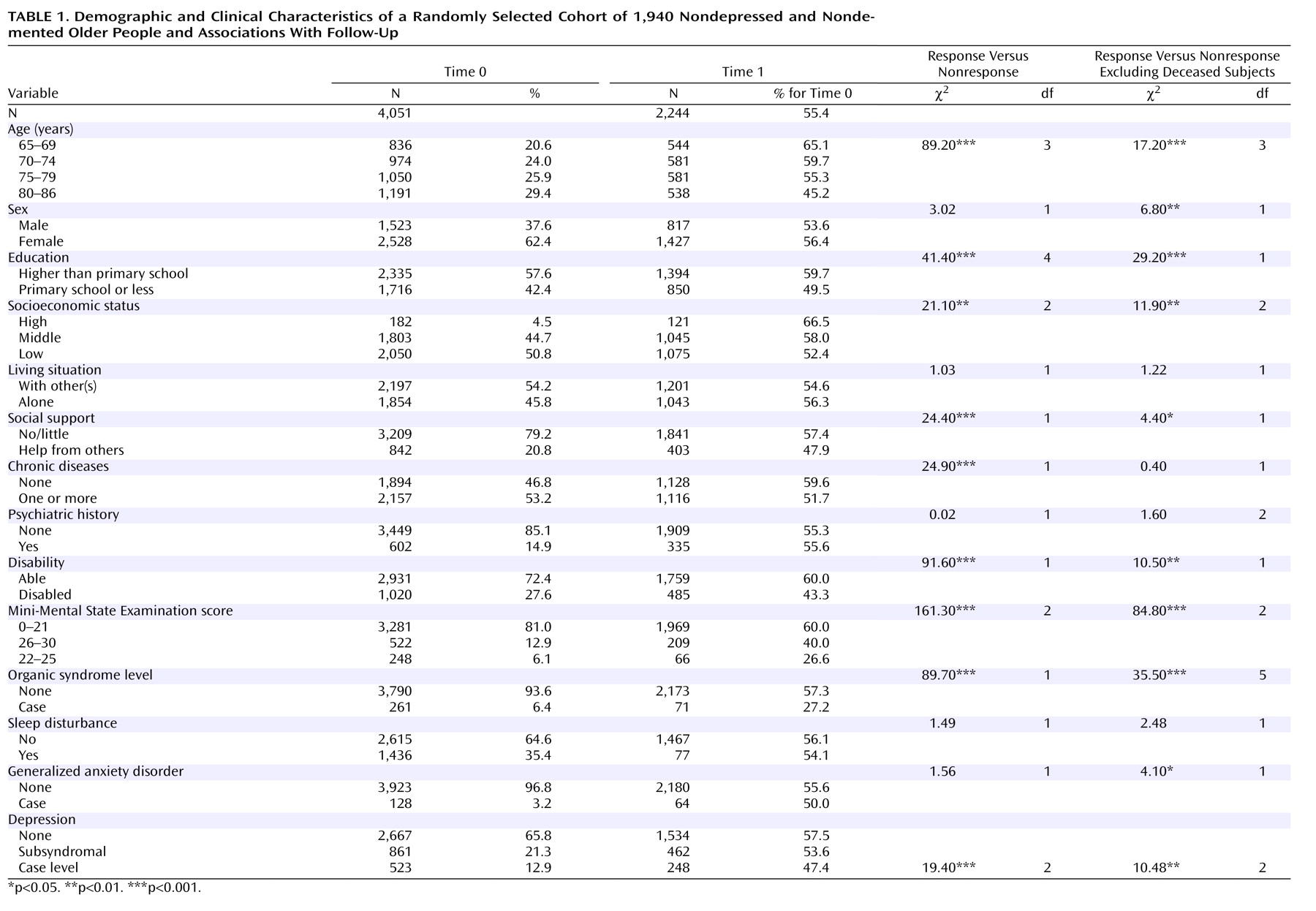

The Amsterdam Study of the Elderly is a large prospective cohort study with long follow-up intervals, and it incorporated a wide range of risk factors for late-life depression measured independently of depression onset. The findings are representative for urban populations of community dwelling older persons, and are highly relevant for primary care.

Nonetheless, a number of limitations deserve mentioning. First of all, studies with a limited number of measurements tend to overrepresent chronic forms of disorder. Between assessments, subjects may have had both onset and remission of shorter episodes of depression. At the same time, it may be concluded that even with a 3-year interval, the set of risk factors employed in this study can identify a large number of future cases of depression. Second, although the risk factors cover many domains relevant to depression, biological (genetic) risk indicators are less well represented in the data set. Other factors that would ideally have been available are medication use, substance abuse or dependence, and specific medical conditions, such as thyroid disorders that may be associated with depression onset. Third, it should be concluded that this study does not prove that preventative interventions are successful in community-living elderly. Available studies on indicated prevention were mostly performed in younger adults. However, because other forms of treatment of depression are also effective in the elderly, there would be no reason to doubt the efficacy of preventative interventions in elderly subjects. When considering the potential benefits of prevention, there is an urgent need for randomized, controlled trials to address this matter.