Mental illness is among the most important health concerns facing American Indian communities today. Telepsychiatry, in the form of live interactive videoconferencing, has the potential to address many of the challenges of clinical service and research among rural American Indians

(1) . Although they have been encouraging, the handful of articles on American Indian telepsychiatry is limited to case reports and program descriptions

(2 –

4) . To our knowledge, no well-controlled studies exist regarding the impact of videoconferencing on psychiatric assessment and diagnosis in this special population. Several investigators have addressed the reliability, validity, and feasibility of administrating structured clinical interviews, including the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (SCID), by means of interactive videoconferencing in other patient populations

(5) . The study most relevant to this report examined the reliability of SCID diagnoses of major depression, bipolar disorder, panic disorder, and alcohol dependence among 15 veterans assessed face-to-face and by means of videoconferencing

(6) .

Panic disorder had the greatest concordance; major depressive disorder, the least. Although these results were promising, this study was limited by its small size, its exclusion of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other diagnoses, and its failure to consider how racial status may have affected diagnostic concordance.

Two large-scale studies have demonstrated that the SCID can be administered reliably and validly among American Indians, thus setting the stage for determining whether teleconferencing holds similar promise

(7,

8) .

The purpose of this study was to examine the reliability of the SCID in the administration of psychiatric assessments by means of real-time videoconferencing between an academic medical center and a rural American Indian community. We used an experimental design to randomly assign American Indian military veterans to both face-to-face and real-time interactive video conditions of SCID assessment on two separate occasions within a 2-week period. We hypothesized that diagnoses obtained through videoconferencing would agree with those acquired through face-to-face interviews.

Method

This study was conducted among a rural Northern Plains American Indian reservation population that had participated in a previous study known as the American Indian Vietnam Veterans Project

(8) . When the present study was initiated, veterans from the previous study represented the best sample available of American Indians with a known prevalence of lifetime psychiatric disorders, including PTSD

(8) . The substantial prevalence of well-characterized cases of mental illness was critical to testing the reliability of the SCID in this manner. Bias due to respondents’ prior familiarity with the SCID was minimized by the 8 years or more that had elapsed since the conclusion of the American Indian Vietnam Veterans Project.

A videoconferencing link (an integrated services digital network line, 1¼ T, 384K, with full remote capacity) was established between the American Indian Vietnam Veterans Project and a private room in the community’s Tribal Veterans Center. Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board approval, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act consent, and tribal approvals were obtained before the project’s initiation, as well as written informed consent from each veteran. A power analysis indicated that 50 respondents tested twice would provide 80% power to detect the difference between kappas of 0.6 and 0.8

(9) . A list of available participants was generated from the American Indian Vietnam Veterans Project sample.

In order to achieve adequate power, 20 additional Vietnam-era veterans were identified and recruited from the community. Of the 70 veterans approached, 60 (86%) agreed to participate, of whom 53 (76%) completed both interviews. Thirty-eight (72%) were drawn from the American Indian Vietnam Veterans Project sample. The participants were administered a version of the SCID for DSM-III-R that was modified for the American Indian Vietnam Veterans Project and further adapted in the American Indian Services Utilization, Psychiatric Epidemiology, Risk and Protective Factors Project

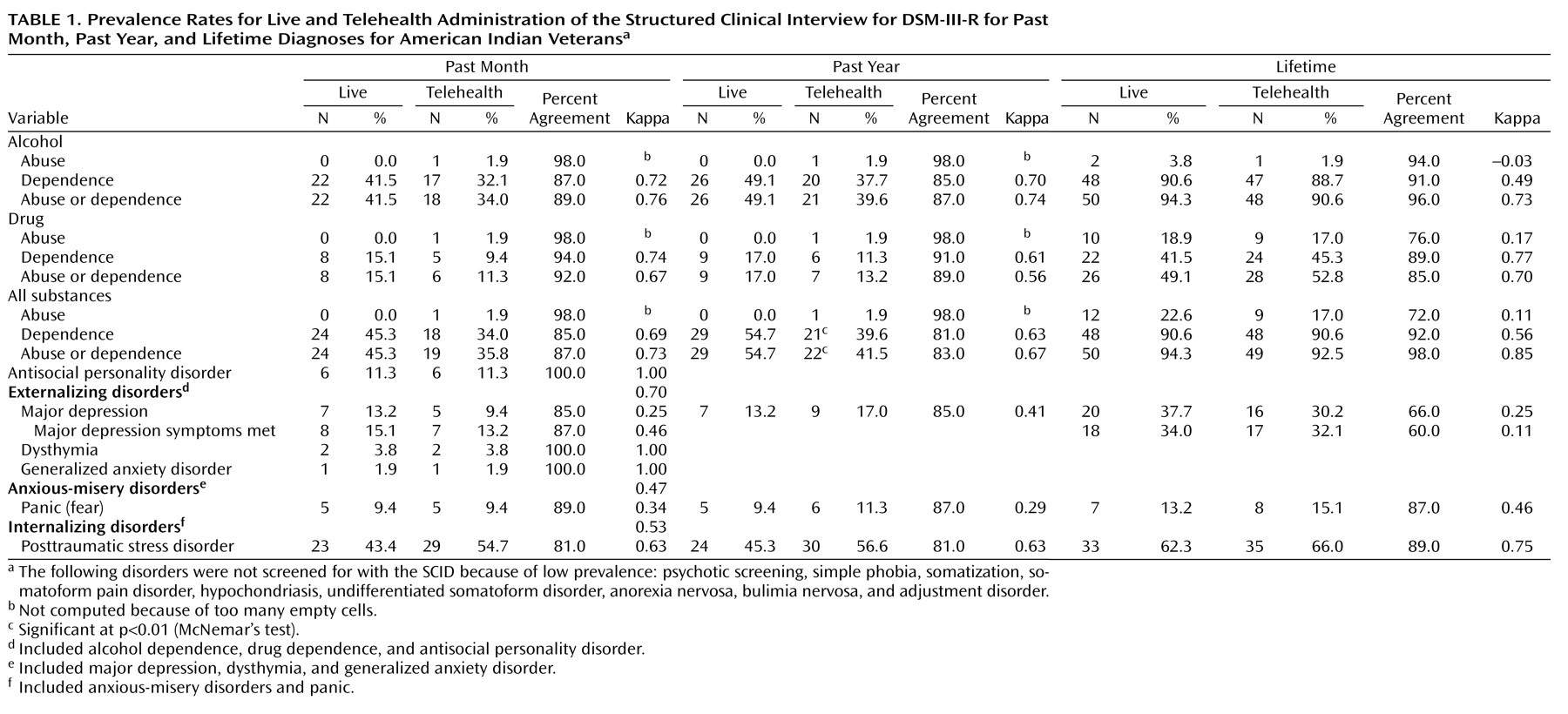

(7) . As in the American Indian Vietnam Veterans Project and the latter studies, several modules were eliminated from the SCID because of the low rate of the disorders in question (

Table 1 ). Minor modifications of the SCID were made in the American Indian Vietnam Veterans Project to render some questions more culturally relevant. Two American Indian Vietnam Veterans Project psychiatrists were selected and trained to administer the SCID. Both had extensive experience working with American Indians and PTSD in cross-cultural settings. The interviewers were trained to administer the SCID in the same manner as in the American Indian Vietnam Veterans Project and the American Indian Services Utilization, Psychiatric Epidemiology, Risk and Protective Factors Project. Videotapes created specifically for the latter projects were used to assess interrater reliability, with an average kappa >0.80 obtained by both interviewers. Once enrolled, the participants were randomly assigned to either of two conditions: 1) a real-time interactive videoconference followed by a face-to-face interview or 2) a face-to-face interview followed by a real-time interactive videoconference. The paired SCIDs were to be completed within 2 weeks of each other (average time between interviews, 10.8 days). The face-to-face interviews were conducted at a private office in the community. For the real-time interactive videoconferencing, the participants were seen at the Tribal Veterans Program; the interviewer was located in Denver. Interviews took between approximately 80 and 90 minutes to complete in both conditions. No one else was present during the interviews.

The interviews were conducted in 2003, spanning 12 months, in four cohorts of approximately 10–15 participants each. Completed SCIDs were keyed into a computer; the resulting data were transformed into an SPSS file

(10), cleaned, and organized in system files for analyses. In order to determine if the interview sequence had an effect on the diagnosis of disorders, a paired T test for dependent samples was performed; no significant difference was found. The prevalence of each diagnosis was calculated for both assessment modalities. In order to compare the proportion of participants with a particular diagnosis from the face-to-face session to the proportion from the videoconference session, McNemar’s test for dependent data was used

(11) . Interrater reliability between the two administration modalities was assessed with the kappa statistic, which accounts for agreement that occurs by chance. Cutoff values suggested by Byrt

(12) were used to classify kappa estimates as excellent (>0.92), good/very good (>0.6), and fair (>0.4). One limitation of the kappa statistic is that it tends to be underestimated when the true prevalence in the population of interest is low

(13) . Because the prevalence of several of the diagnoses was low in this population, the percent agreement was also calculated

(13) . An emerging pattern led to further examination of the kappas by diagnoses that can be classified as internalizing or externalizing disorders. Grouping diagnoses in these terms was informed by an analysis from the National Comorbidity Survey

(14) ; kappa statistics were calculated for past month.

Results

The sample was relatively homogenous. All subjects were American Indian male Vietnam-theater and -era veterans from a Northern Plains tribe. The mean and median age was 54 years (range=46–71). Ninety percent had been previously married, and 32% were currently married. Half of the sample (53%) had completed some form of higher education, and 30% had completed high school/the graduate educational development (GED) test or trade school.

Table 1 presents the prevalence and reliabilities by diagnosis for the past month, the past year, and lifetime by modality. With the exception of past-year substance dependence and abuse/dependence combined, there were no significant differences in prevalence between the face-to-face and live interactive videoconferencing modalities. Percent agreement between modalities was greater than 80%, except for lifetime drug abuse (76%), lifetime substance abuse (72%), and lifetime major depressive disorder (66%). The majority (76%) of kappa statistics were classified as good agreement or fair agreement (greater than 0.6)

(12) . Externalizing disorders elicited a higher kappa (0.73) than internalizing disorders (0.53).

Discussion

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to examine the diagnostic reliability of administering a structured clinical interview by means of videoconferencing to American Indians. We believe that it is also the largest reliability study of the administration of the SCID by these means and the first to examine the reliability for PTSD, substance abuse and dependence, generalized anxiety disorder, and antisocial personality disorder. Overall, with some notable exceptions, SCID assessments by videoconferencing did not differ significantly from those obtained in face-to-face interviews.

Our data indicate that, with the exception of PTSD, SCID assessments by videoconferencing with this population may more easily detect externalizing disorders. The criteria for externalizing disorders are more behavioral and less subjective by nature, possibly rendering these symptoms easier to elicit through this modality. It may be more difficult to engage individuals with internalizing disorders through videoconferencing and thus identify relevant symptoms. PTSD possibly represents a unique internalizing diagnosis, one in which the real-time interactive videoconferencing actually enhances symptom reporting

(3) .

This study has several limitations. The 2-week interval between interviews could have introduced symptom changes affecting the reliability of current diagnoses. The low prevalence of certain disorders precluded meaningful conclusions about diagnostic reliability. The high prevalence and comorbidity of most conditions may have complicated the diagnosis of any specific disorder. The ethnic homogeneity limits our ability to generalize these findings to other populations.

Despite its limitations, this study represents an important first step toward understanding the diagnostic reliability of administering important clinical tools such as the SCID among American Indian veterans. This is especially timely because clinical work along these lines is already in process

(4) . The next steps should include determining the impact of cultural factors on this technology and identifying additional clinical tools for telepsychiatric application and adaptations needed in clinical and research protocols to improve the reliability of telepsychiatric assessment.

The capacity of this technology must be better understood in order to bend it to our clinical and research needs, with American Indians as well as other rural minority populations to fulfill its promise of increasing both access and quality of care.