Within-Subject Change in CBCL and Vineland Scores

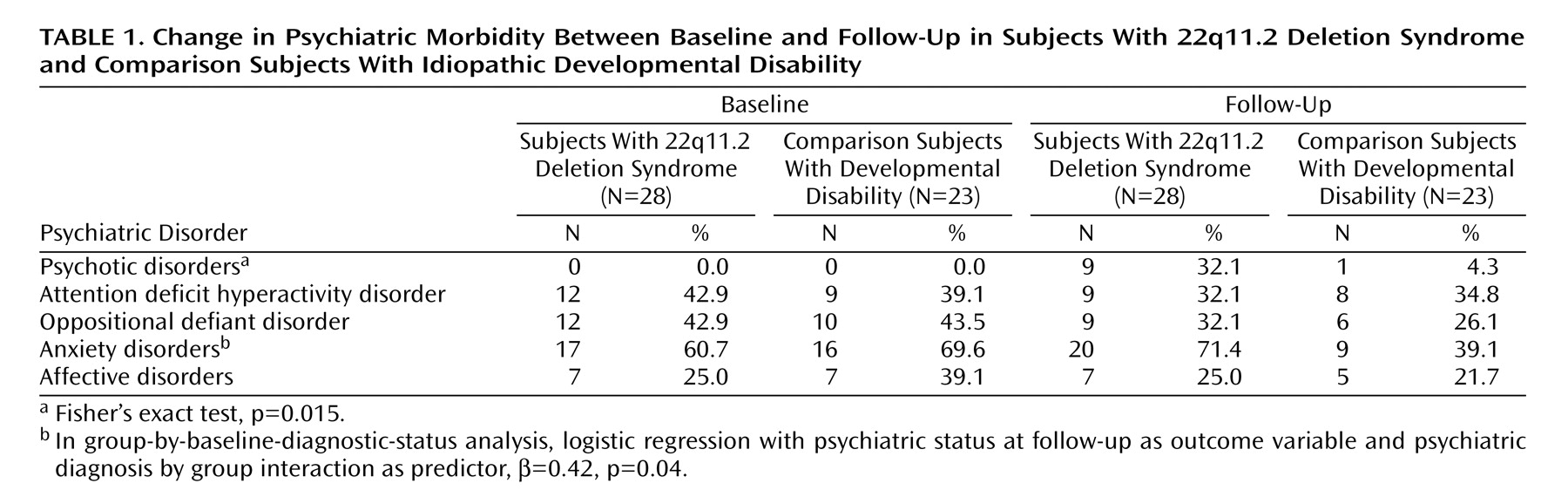

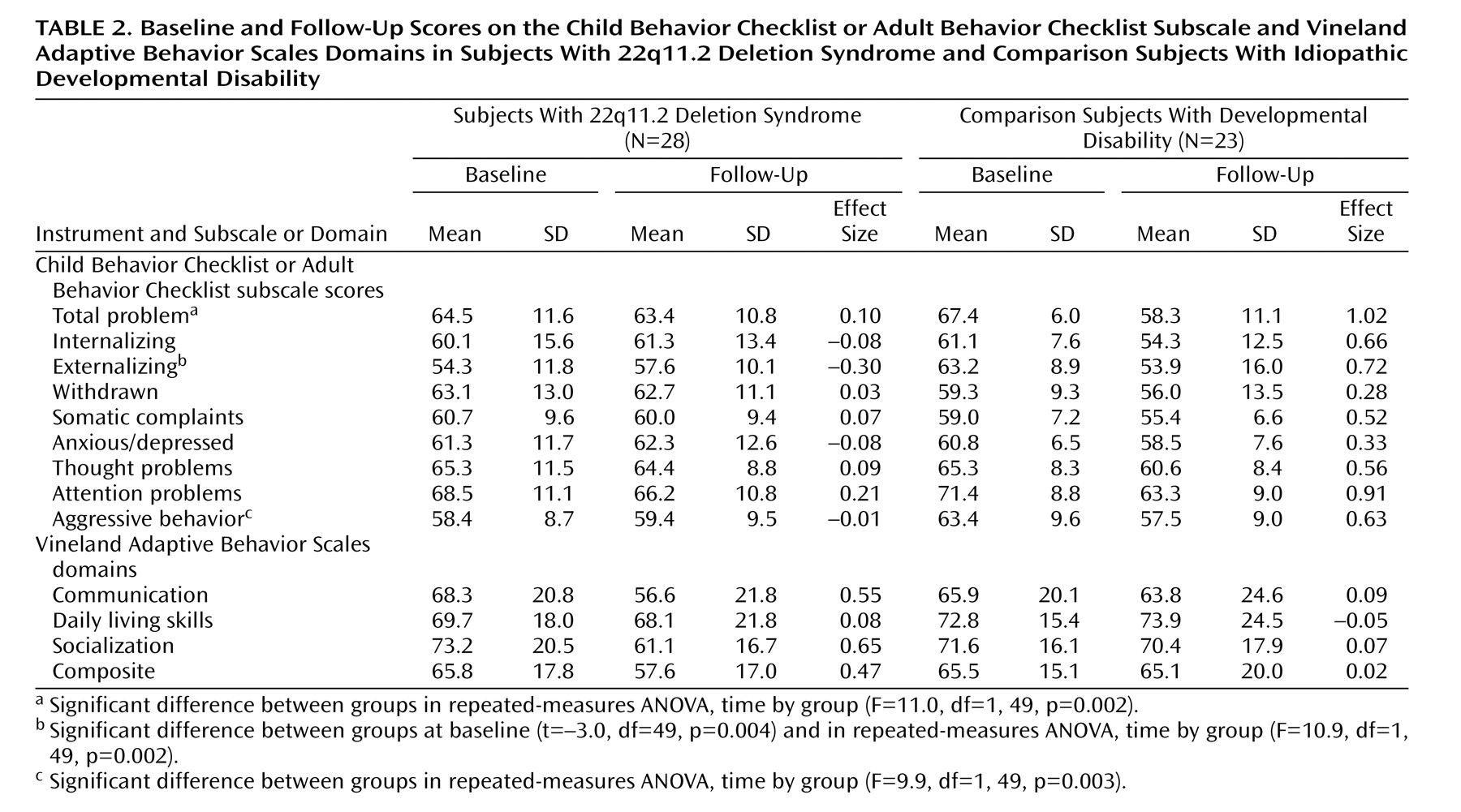

At baseline, the CBCL externalizing scores were significantly higher in the comparison group than in the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome group (

Table 2 ). No other significant differences were found between groups on any other CBCL or Vineland score. Repeated-measures ANOVAs showed that, after correction for multiple comparisons, changes in total problem, externalizing, and aggressive behavior scores differed significantly between groups, with the comparison group exhibiting a greater decrease in scores from baseline to follow-up compared with the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome group (

Table 2 ). Post hoc pairwise t tests indicated that total problem (t=4.5, df=22, p<0.0001), externalizing (t=2.6, df=22, p<0.05), and aggressive behavior (t=3.5, df=22, p<0.005) scores significantly declined in the comparison group and did not significantly change in the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome group.

The CBCL thought problems scores for the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome group remained stable, although a large proportion of subjects in this group developed psychotic disorders; those with psychotic disorders had higher thought problems scores at follow-up than those without psychotic disorders (70.2 [SD=6.5] versus 61.6 [SD=8.6]; t=–2.7, df=26, p=0.01). In the comparison group, thought problem scores significantly declined between baseline and follow-up (t=2.4, df=21, p<0.05).

Prediction of Psychosis in 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome

To identify the best set of baseline predictors for the development of psychotic disorders at follow-up, forward hierarchical/stepwise regression analysis was performed for the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome group. Because we found in a previous study that the COMT Met/Val genotype predicted the severity of psychotic symptoms

(3), we entered the COMT genotype in the first step. Since our a priori hypothesis was that the presence of subthreshold and above-threshold psychotic symptoms at baseline would predict the development of a full-blown psychotic disorder at follow-up, the baseline psychosis scale was entered in the second step. At the third step, we entered all other predictors, including baseline prefrontal and temporal gray matter volumes adjusted for total cranial gray matter volume, baseline verbal IQ, and baseline CBCL factor scores on the withdrawn, anxious/depressed, thought problems, attention problems, and aggressive behavior subscales. The CBCL predictors were chosen on the basis of reports in the schizophrenia literature associating these prodromal or premorbid symptoms as potential risk factors for the development of psychosis

(8,

9,

27 –29) .

Results from the logistic regression analysis indicated that at the first step, the COMT genotype was significantly associated with the presence of a psychotic disorder at follow-up (β=1.81, p<0.05). At the second step, psychotic symptoms at baseline were significantly associated with the presence of a psychotic disorder at follow-up (β=1.79, p<0.05). Of the third-step variables, only the CBCL anxious/depressed subscale scores were significantly associated with the presence of a psychotic disorder at follow-up (β=0.20, p<0.05).

Converging results were obtained when predicting follow-up BPRS scores with the same dependent variables. The hierarchical/stepwise linear regression analysis showed that COMT genotype predicted 24% of the variance in BPRS scores (β=0.49, r 2 change=0.24, p=0.01), baseline psychotic symptoms scores predicted 20% of the variance in BPRS scores (β=0.45, r 2 change=0.20, p<0.01), and CBCL baseline anxious/depressed scores accounted for an additional 23% of the BPRS scores’ variance (β=0.66, r 2 change=0.23, p=0.001). In addition, lower verbal IQ scores at baseline were significantly associated with BPRS scores and predicted an additional 7% of the variance (β=–0.26, r 2 change=0.07, p<0.05).

To evaluate possible interaction between baseline variables that significantly predicted the onset of psychotic disorders at follow-up, we conducted an additional linear regression analysis in which follow-up BPRS was the outcome variable and the predictors included the following interactions: COMT genotype by baseline psychotic symptoms, COMT genotype by baseline CBCL anxious/depressed scores, and baseline psychotic symptoms by baseline CBCL anxious/depressed scores. Baseline psychotic symptoms by baseline anxious/depressed scores strongly predicted BPRS scores (β=0.12, p=0.001); COMT genotype by baseline psychotic symptoms scores also strongly predicted BPRS scores (β=6.51, p=0.002). Together, these two predictors accounted for 61% of the variance in BPRS scores.

The CBCL subscales for withdrawn, thought problems, attention problems, and aggressive behavior as well as the baseline prefrontal and temporal gray matter volumes were not found to predict the development of psychotic disorders in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome in both regression analyses.

The association between psychotic symptoms at baseline and the presence of psychotic disorders at follow-up was specific to the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome group; none of the four subjects in the developmental disability group with subthreshold or above-threshold psychotic symptoms at baseline developed a psychotic disorder, whereas five of eight children in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome group who had psychotic symptoms at baseline had developed a psychotic disorder by follow-up.

The presence of any anxiety disorder (not including phobias) at baseline was strongly associated with the development of psychotic symptoms at follow-up (p<0.005). Interestingly, all four subjects in the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome group who had a diagnosis of OCD at baseline met diagnostic criteria for a psychotic disorder at follow-up.