Schizophrenia is a complex disorder with several replicated genetic linkages reported

(1) . Since disordered cognitive functioning is a hallmark of schizophrenia, progress in understanding its pathophysiology mandates integration of genetic and neurobiological research. Consistent with anatomic and physiologic findings of frontotemporal dysfunction, neurocognitive measures have indicated deficits in executive domains, learning, and memory

(2,

3) . The potential of neurocognitive measures as markers of genetic liability is supported by studies showing intermediate deficits in attention and memory in unaffected relatives

(4 –

9) .

Given the heterogeneity of schizophrenia at the phenotypic and likely genotypic levels, analyzing neurobiological phenotypes may improve power to detect susceptibility loci by constraining some heterogeneity. The possibility that endophenotypes are genetically simpler than disease endpoints is one of their advantages. Furthermore, these quantitative parameters can be measured in family members, where a clinical diagnosis may be absent or difficult to establish. Another advantage is that continuous quantitative traits have inherently more resolution than dichotomous traits. Most important, however, cognitive traits are increasingly being linked to neural systems that will provide more direct mechanistic windows, eventually permitting subcategorization of schizophrenia based on differences in pathophysiology.

The present study examines quantitative neurocognitive measures as candidate endophenotypic markers in multiplex multigenerational families. Our approach requires a different ascertainment strategy from that used in most syndrome-based phenotyping for genetic analysis

(10) . Specifically, the power to detect genes for quantitative traits through linkage analyses increases with family size

(11), making extended multigenerational families rather than sibpairs the cohort unit of choice. Because the endophenotypes can be measured in unaffected family members, smaller cohort sizes of probands are necessary. If neurocognitive deficits are associated with genetic liability, they should increase with presumed genetic loading for schizophrenia. Investigations with simplex and multiplex families have supported an additive model in which increased genetic risk is accompanied by increased impairment in language

(12), intelligence, verbal memory, visual reproduction

(13), visual working memory

(14), verbal learning, delayed visual recall, and perceptual- and pure-motor speed

(15) . In this first report, we characterize the neurocognitive profile of multiplex multigenerational families with schizophrenia and provide heritability estimates of neurocognitive measures.

Method

Written informed consent was obtained after the procedures had been fully explained. In the case of children (<18), the child’s assent and parental consent were obtained.

Participants

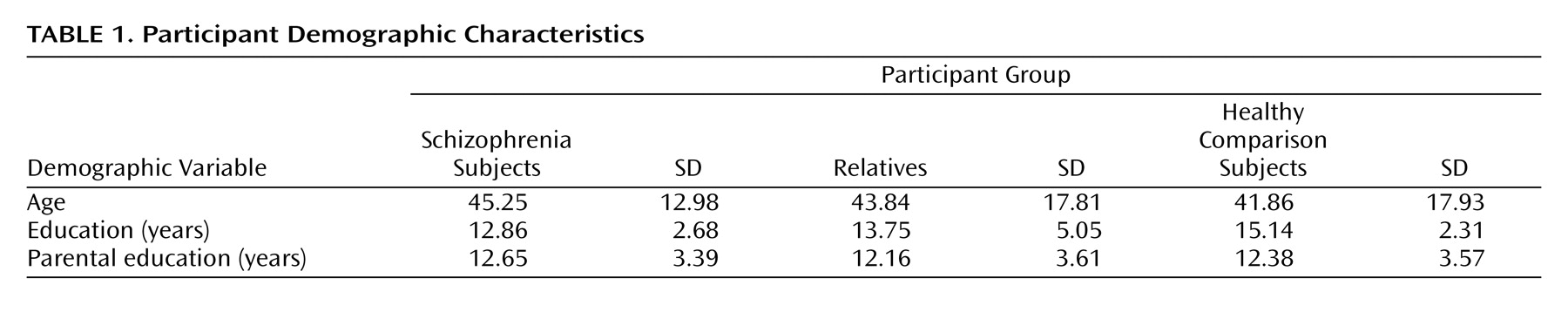

The cohort included 349 European Americans from 35 multiplex multigenerational families (average family size 10.51 [SD=8.46] members, range: 3–32), who met inclusion criteria. A normative group included 154 medically and psychiatrically healthy European Americans ages 19 to 84. Comparison subjects, patients (N=58), and relatives (N=291) did not differ significantly in age and parental education. As expected, patients attained less education than family members and comparison subjects (

Table 1 ). The male:female ratio was as follows: schizophrenia group: 34:24, relatives: 144:147, and comparison subjects: 76:78.

The mode of ascertainment was population based. Potential participants were identified through mental health and consumer organizations in Pennsylvania and bordering states. Suitability for the study was determined based on specified inclusion and exclusion criteria established by standardized screening and assessment. Healthy comparison subjects were recruited from the same communities as probands and families.

Participating probands were older than 18 years and could provide signed informed consent. They met consensus best-estimate DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia and had at least one first-degree affected family member with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, depressed type. In addition, they had an extended multigenerational family, with at least 10 first- and second-degree relatives. Potential probands were excluded if they did not provide written consent to contact family members, their psychosis was linked to substance-related disorders by DSM-IV criteria, they had mental retardation (IQ<70), they had a history of a medical disorder or they were receiving medication that may cause psychosis or neurocognitive deficits, or they were not proficient in English.

Participating family members were older than 15 years and could provide signed informed consent. Family members were excluded if they had mental retardation (IQ<70), a CNS disorder that may render neurocognitive measures noninterpretable, or were not proficient in English. The exclusion criteria applied to the neurocognitive measures, but if diagnosis was established, blood samples were obtained. Potential healthy comparison participants underwent standard screening procedures followed by the same assessment procedure to establish the absence of axis I and cluster A axis II disorders. They were psychiatrically, medically, and neurologically healthy, receiving no psychotropic medications, and reported no first-degree relative with psychosis or mood disorder.

Procedures

Diagnostic assessment

The psychiatric evaluation included the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies, version 2.0

(16), the Family Interview for Genetic Studies

(17), and review of medical records. The Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies was always conducted in person, and the Family Interview for Genetic Studies was conducted in person with at least two family members and, if necessary, by phone when another family member was particularly informative. Interviews were conducted by trained interviewers with established reliability and under the supervision of investigators. A summary statement narrated the history, interview, mental status, examples of answers, and observations.

Two investigators who had not evaluated the individual reviewed each case independently and provided DSM-IV multiaxial lifetime diagnoses. Subjects with psychotic features or disagreement between the investigators were presented in consensus conference, and complex cases were discussed between sites. At each site, interrater reliability among investigators and interviewers was tested at regular intervals using videotaped interviews and bimonthly joint interviews. The interviewers viewed 10 videotaped Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies evaluations exchanged between the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Pittsburgh, maintaining kappa values >0.8. The teams met twice a year for diagnostic, reliability, and training purposes.

Neurocognitive measures

Participants were administered a computerized neurocognitive “scan” previously applied to healthy individuals

(18) and patients with schizophrenia

(19) . It is an efficient test battery administered by research assistants using desktop or portable computers. The battery, designed for large-scale studies, includes a training module and has automated scoring with direct data downloading. The battery assesses the following eight domains:

Abstraction and mental flexibility . The Penn Conditional Exclusion Test

(20) presents four objects at a time, and the participant selects the object that does not belong with the other three based on one of three sorting principles. Sorting principles change, and feedback guides their identification (time: 12 minutes).

Attention . The Penn Continuous Performance Test

(21) uses a continuous performance test paradigm where the participant responds to seven-segment displays whenever they form a digit. Working memory demands are eliminated because the stimulus is present (time: 8 minutes).

Verbal memory . The Penn Word Memory Test

(22) presents 20 target words followed by an immediate recognition trial with targets interspersed with 20 distractors equated for frequency, length, concreteness, and low imageability using Paivio’s norms. Delayed recognition is measured at 20 minutes (time: 4 minutes).

Face memory . The Penn Face Memory Test

(22) presents 20 digitized faces subsequently intermixed with 20 foils equated for age, gender, and ethnicity. Participants indicate whether or not they recognize each face immediately and at 20 minutes (time: 4 minutes).

Spatial memory . The Visual Object Learning Test

(23) presents 20 Euclidean shapes subsequently interspersed with foils immediately and at 20 minutes (time: 4 minutes).

Spatial processing . Judgment of Line Orientation

(24) is a computer adaptation of Benton’s test. Participants see two lines at an angle and indicate the corresponding lines on a simultaneously presented array (time: 6 minutes).

Sensorimotor dexterity . The participant uses a mouse to click on squares appearing at varied locations on the screen

(18) . The stimuli become progressively smaller (time: 2 minutes).

Emotion processing . Identification of facial affect was tested with a 40-item Emotion Intensity Discrimination Test

(25) . Each stimulus presents two faces of the same individual showing the same emotion (happy or sad) with different intensities. The participant selects the more intense expression. Sets were balanced for gender, age, and ethnicity (5 minutes).

Administration and scoring

The battery was administered in a fixed order using clickable icons. Its administration took about 60 minutes. All except 33 participants yielded valid data for all measures. Missing data occurred because of technical difficulties or failure to follow instructions. Raw scores were converted to z scores using the comparison group mean and then averaged to obtain domain scores. The following two performance indices were calculated: 1) accuracy—the number of correct responses—and 2) speed—the median reaction time for correct responses. Only speed was examined for the sensorimotor dexterity domain because 75% of participants achieved perfect accuracy.

Statistical Analyses

Differences in neurocognition among groups were analyzed by hierarchical linear modeling

(26) using the SAS PROC MIXED routine

(27) . Family data consist of two hierarchical or multilevel units: participants (level 1) are nested within families (level 2). Because family members are not independent observations, the assumption of independence in analysis of variance (ANOVA)-based methods is violated in the presence of hierarchical data. In practice, we have found endophenotype deficits in family members to be robust to this violation

(28,

29) . However, hierarchical linear modeling formally addresses this problem by modeling the interdependence among members of the same family through testing for a random effect for families

(30) . Moreover, hierarchical linear modeling provides more flexibility than ANOVA-based methods in the face of missing data (e.g., scores on a particular task); participants with missing data are not eliminated from analyses

(26) .

First, multivariate hierarchical linear modeling analyses were conducted for accuracy and speed to examine overall group effects (schizophrenia, relative, comparison group) and group-by-domain (abstraction and mental flexibility, attention, verbal memory, face memory, spatial memory, spatial processing, sensorimotor dexterity, emotion processing) interactions. Second, for any significant overall effect, pairwise (schizophrenia versus comparison group, relative versus comparison group, schizophrenia versus relative group) multivariate hierarchical linear modeling analyses were conducted to determine pairwise differences. Finally, univariate post hoc hierarchical linear modeling analyses were conducted to determine specific cognitive domains in which groups differed. For these analyses, we also examined family-by-diagnosis interactions on the domain scores.

To maximize power and generalizability, the initial analyses included all ascertained relatives unaffected with schizophrenia, regardless of other axis I or II diagnoses. However, the inclusion of more distant relatives is expected to dilute the appearance of a deficit because of the increased genetic distance from a person with schizophrenia. Consequently, we also compared first-degree relatives with more distant relatives. To address the potential influence of other psychiatric diagnoses in relatives, the hierarchical linear modeling analyses were also repeated, including only medically and psychiatrically healthy first-degree relatives

(28) . Although the groups did not differ in age and parental education, because of the importance of these demographic factors the hierarchical linear modeling analyses added age, education, and parental education as covariates in the mixed model.

Estimation of Heritability

Standard maximum likelihood variance component methods implemented in SOLAR

(31) were used to model estimated heritabilities. We compared a matrix of observed covariances among family members with matrices that predicted what this sharing should look like based on shared deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), and we used maximum likelihood methods to estimate what portion of the population variance in the trait would be the result of additive genetic sharing. Thus, each individual’s performance on the neurocognitive domains was modeled as a function of measured covariates, specifically age and sex, additive genetic effects estimated from correlations among family members, and individual-specific residual environmental factors. A likelihood ratio test was used to assess statistical significance. Variance component methods generally assume that traits are normally distributed and are particularly sensitive to kurtosis in the trait distribution

(32) . Use of a multivariate t distribution instead of the multivariate normal has been shown to be robust to kurtosis in the trait distribution

(33) . All analyses reported in this study used the multivariate t distribution. Since 75% of participants had identical values for sensorimotor dexterity accuracy, this trait was dichotomized and analyzed using a liability threshold model

(34) .

It is noteworthy that the heritability estimates calculated in multigenerational extended families are unlikely to be substantially inflated by shared environment. It would be extremely unlikely for environmental sharing to decay in a Mendelian-like manner. For shared environment to mimic genetics in an extended family, aunts, uncles, nieces, and nephews would need to be half as correlated for environment as parents, siblings, and children, and cousins would need to be half as correlated as aunts, uncles, etc., based on their expected DNA sharing. Each step on the family tree would require a fixed proportional decrease in shared environment for it to mimic the additive genetic component we are estimating and thereby inflate our heritabilities. Here lies the major advantage of the multigenerational design. When the cohort only includes nuclear families (with parents and nontwin children), it is impossible to separate out shared environment from certain types of genetic effects. The matrix that predicts additive genetic covariance structures our estimation of the presumptive heritability.

Results

Neurocognitive Profile

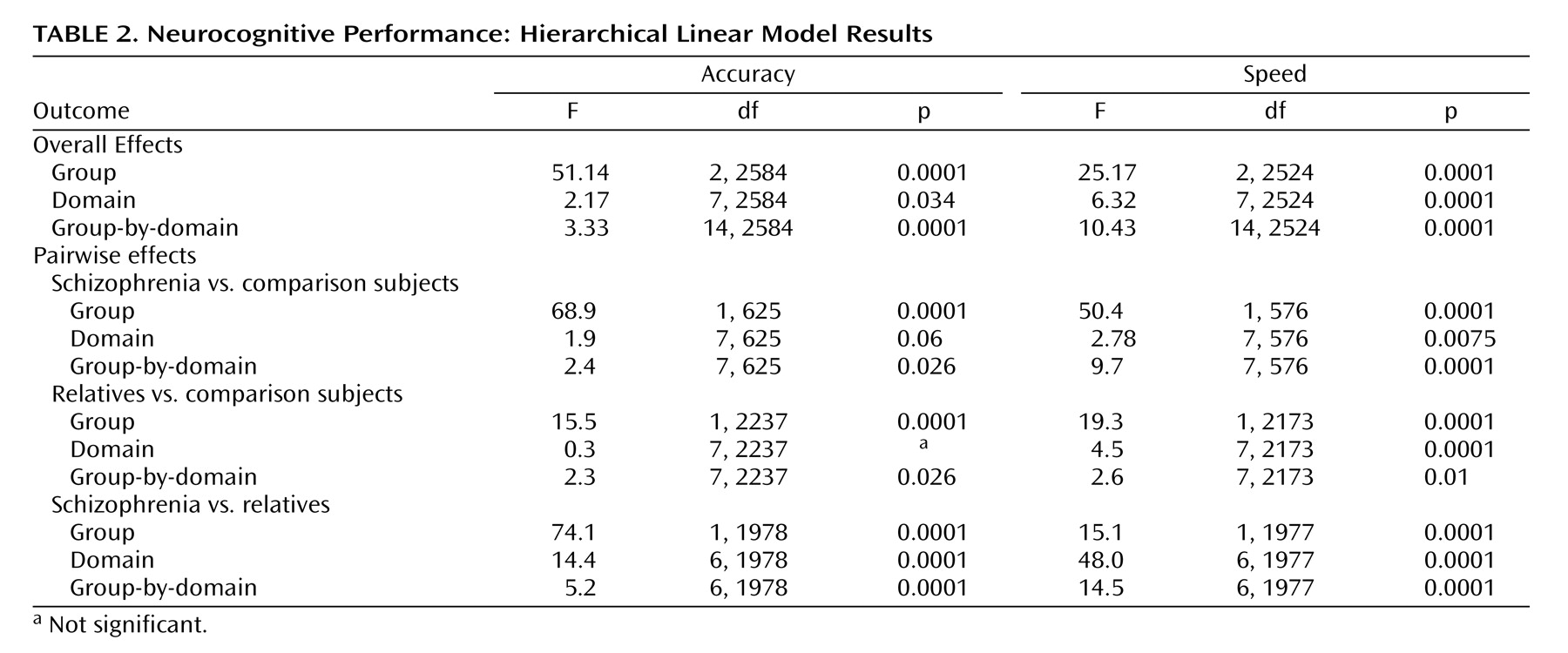

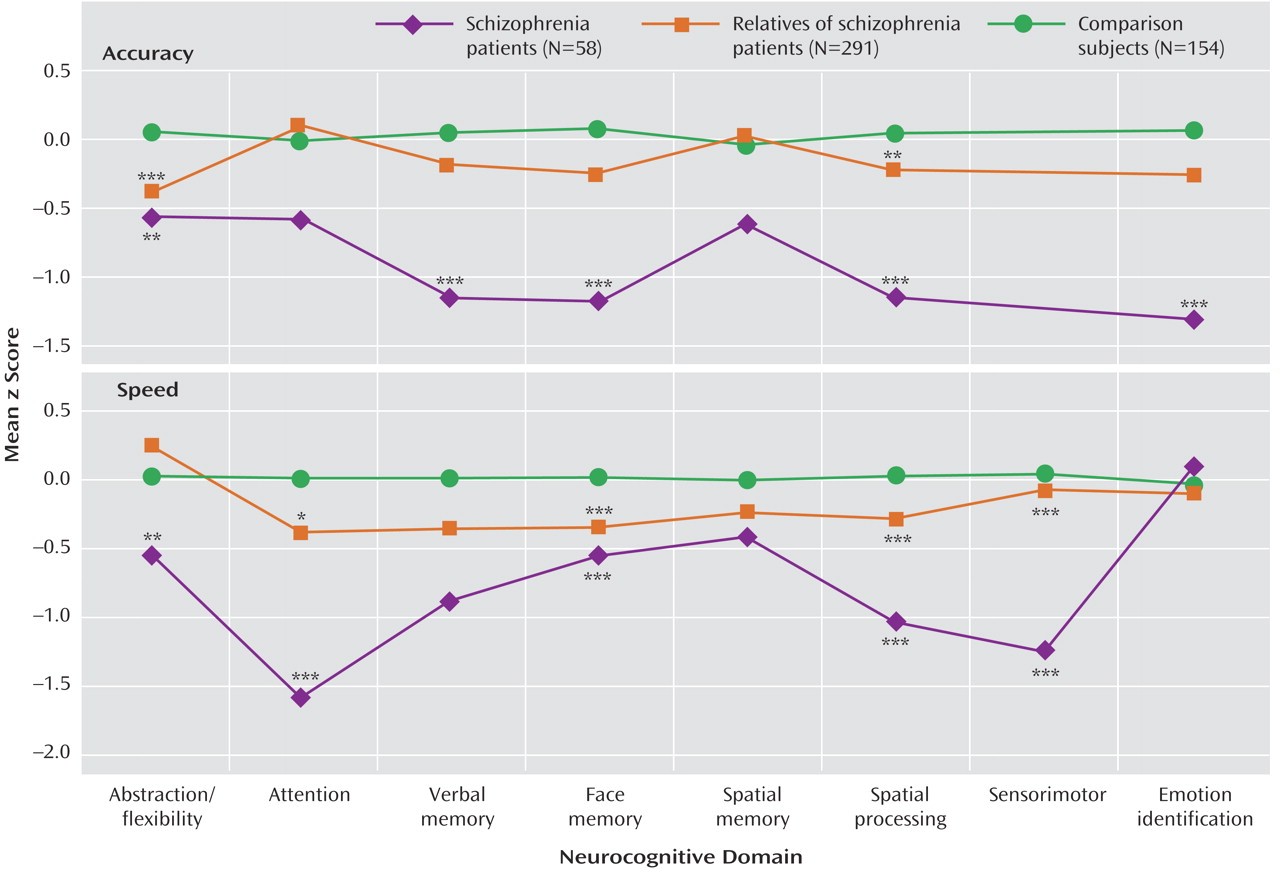

Multivariate hierarchical linear modeling effects are presented in

Table 2 . For each of the two indices (accuracy, speed), hierarchical linear modeling was highly significant for group and group-by-domain interactions, warranting follow-up pairwise multivariate hierarchical linear modeling to determine the source of the significant effects. Pairwise group effects were significant, indicating that all groups differed from each other in accuracy and speed. The group-by-domain interactions were likewise highly significant for all pairwise comparisons. Group profiles, showing patients with schizophrenia, relatives, and comparison subjects, are presented in

Figure 1 . As can be seen, individuals with schizophrenia performed most poorly across domains and measures, while relatives performed at an intermediate level between patients and healthy comparison subjects.

Although relatives performed worse than comparison subjects across neurocognitive domains, the group-by-domain interaction indicated differential effects of presumptive genetic liability on domain of impairment. Furthermore, some deficits were more pronounced for accuracy while others for speed. Most conspicuously, relatives had impaired accuracy but normal speed for abstraction and flexibility, while for attention they had normal accuracy but substantially reduced speed. There were no significant family-by-diagnosis interactions on the summary measures of the neurocognitive domains.

To evaluate the effects of genetic relatedness and add to comparability with nuclear family studies, we examined first-degree relatives separately. This group performed more poorly than comparison subjects across domains and showed a group-by-domain interaction for accuracy (group: F=31.09, df=1, 864, p<0.0001; group-by-domain: F=2.23, df=7, 864, p=0.0303) and speed (group: F=37.09, df=1, 808, p<0.0001; domain: F=2.40, df=7, 808, p=0.0195; group-by-domain: F=3.45, df=7, 808, p=0.0012). Indeed, univariate contrasts showed poorer performance in first-degree relatives for all domains except abstraction and mental flexibility, where they had decreased accuracy (p=0.0090) but normal speed (p=0.5406); attention, where they had normal accuracy (p=0.4311) but were significantly slower (p=0.0150); and spatial memory, where they did not differ from comparison subjects either in accuracy (p=0.3983) or speed (p=0.3908). On the emotion processing task they were impaired in accuracy (p<0.0001) but not speed (p=0.1585). Finally, including only psychiatrically healthy first-degree relatives yielded nearly identical results to the analysis that included relatives with other axis I disorders. Indeed, none of the differences between healthy relatives and those with another axis I disorder approached significance.

Presumptive Heritability Estimates

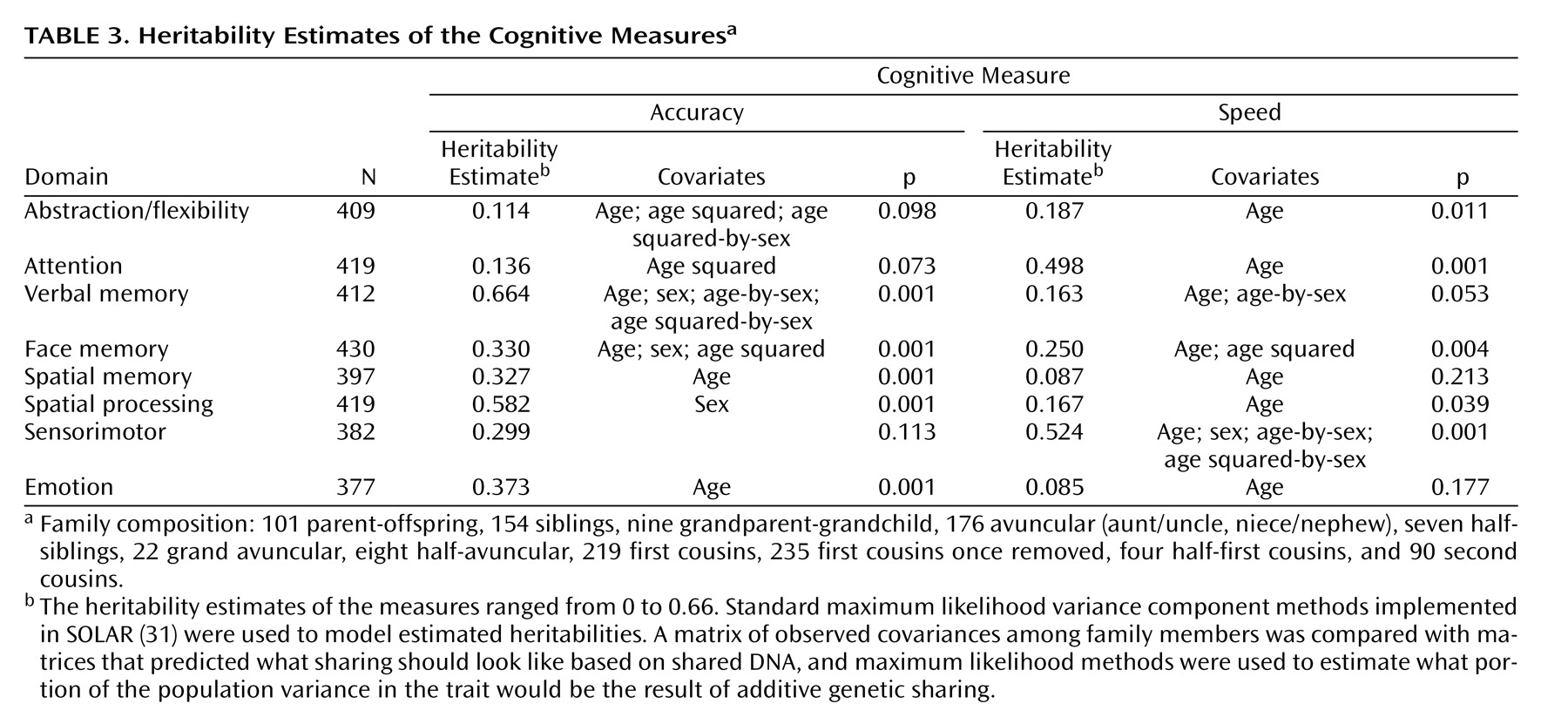

The families involved in this study provide a large number and variety of relative pairs from which the heritabilities were estimated (

Table 3 ). There were over 150 sibling pairs and over 175 cousin pairs, with relatives as distant as second cousins. However, it should be noted that the unit of analysis was actually the correlation matrix for an entire family rather than separate relative pairs.

Most measures showed age effects, with mean values declining with increasing age. Sex differences were observed on three neurocognitive domains, with women performing more accurately on verbal and face memory and men performing more accurately on the spatial task. The heritability estimates of the measures ranged from 0 to 0.69. Four neurocognitive domains (verbal memory, face memory, spatial memory, spatial processing) and emotion processing showed significant heritability estimates for accuracy and the other two (abstraction and mental flexibility, attention) showed significant heritability estimates for speed.

Discussion

We found in a multiplex multigenerational cohort that probands with schizophrenia were impaired across a range of neurocognitive domains and that relatives without schizophrenia also showed impairment in specific domains compared with healthy comparison subjects without family history. This finding confirms, with a computerized battery, earlier reports based primarily on paper and pencil tests

(2 –

8) . The computerized procedure enables effective and errorless measurement of neurocognitive functions in large-scale studies, guaranteeing uniformity of data collection and scoring across sites. The finding also supports the potential of neurocognitive measures as endophenotypic markers of vulnerability to schizophrenia. Additionally, we established presumptive heritability estimates for these measures and found some to be significant, ranging from small to substantial.

The computerized measures permit additional insight into the interplay between accuracy and speed, reflecting cognitive strategies

(35,

36) . Probands and relatives were impaired overall across functions in accuracy, speed, or both. However, relatives showed considerable variability in speed for the different domains, as reflected in the group-by-domain interaction; for example, relatives had impaired performance accuracy on the abstraction and mental flexibility domain while working at normal speed. On the attention domain, by contrast, they had normal accuracy but at the expense of slowed response time. For other functions where both speed and accuracy were impaired, the impairment in speed seemed more pronounced.

This suggests that reduced speed could be a compensatory strategy that helps performance but is insufficient when the genetic vulnerability is more severe. Consequently, heritability estimates of most domains were higher for accuracy than for speed. For attention, however, where the compensatory slowing had normalized accuracy, the heritability estimate was not significant for accuracy but high for speed. Thus, examining accuracy and speed separately as endophenotypic markers should improve the specificity of detecting and interpreting genetic effects.

It is noteworthy that emotion processing, which was not examined as an endophenotypic measure in earlier studies, showed impaired accuracy in probands with intermediate accuracy in relatives, whereas both groups were less and about equally impaired for speed. The finding of impaired emotion processing abilities in relatives may relate to poorer social adaptation, which has been observed in families of patients with schizophrenia. It may also relate to the prevalence of schizotypal features observed in relatives, which include social withdrawal and awkwardness

(37,

38) .

A concern in the use of neurocognitive measures as endophenotypic markers is their susceptibility to age effect and the existence of sex differences. The present analysis incorporated an evaluation of these effects and their removal using covariance analysis. The effects we observed were consistent with the literature and buttress the sensitivity of the measures. Yet, our results also indicate that genetic variability can be established after accounting for the moderating effects of age and sex.

The study has several limitations. The unique multiplex multigenerational cohort may yield results that could differ from studies of simplex families with first-degree relatives. However, the neurocognitive profile obtained in the present cohort is similar to that obtained in sporadic schizophrenia

(19) and in other familial cohorts. Furthermore, in a multigenerational design heritability estimates are less likely to be inflated by effects of shared environment, as is the case in studies of first-degree relatives only. Notably, while heritability estimates of most domains were significant, their magnitude was not as high as reported in some twin studies for DSM-based diagnosis. Heritability and familial environment can be confounded in studies of nuclear families, but the present analysis is somewhat protected from this influence because for heritability estimates to be inflated by shared environment, the degree of environmental sharing would have to drop off with the degree of relationship in a manner that resembles Mendelian laws.

In choosing endophenotypes for genetic studies, we need measures that are associated with disease, that differentiate at-risk individuals, and that are heritable. The present results indicate that several neurocognitive measures fulfill these criteria. Specifically, memory and emotion processing accuracy and speed of attention have moderate to strong genetic influences on variation in performance levels between individuals. These traits would be sensible targets for genome scans to identify loci influencing variation in these disease-related risk factors

(39,

40) .