For several decades, pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with streptococcal infection (PANDAS) has been diagnosed, treated, and researched, and studies have shown that symptoms of new and abrupt-onset obsessive-compulsive tendencies and eating disorder are related temporally to a group A streptococcal infection (

1). Research conducted in the early 2000s indicated that paraneoplastic syndromes associated with ovarian teratomas gave rise to NMDA receptor encephalitis, which again brought to light an undeniable connection between the quality, or aberrancy, of immune responses to a peripheral condition, with subsequent neuropsychiatric manifestations of psychosis, paranoia, catatonia, and seizures (

2,

3). Considering the evolving landscape where psychiatry, neurology, and immunology converge, it is important to incorporate all aspects of a presentation into discussions of diagnosis and treatment. Here, we present the case of a patient admitted to the child psychiatric unit with days of escalating mood lability, impulsivity, and aggression in the setting of a urinary tract infection (UTI) and skin infection.

Case

"Leigh" is a 9-year-old girl with no medical or neuropsychiatric history who presented to the emergency department by ambulance. Earlier that afternoon, her parents had arrived home from visiting her uncle where he was recovering from a seizure, a not uncommon occurrence. This time, however, when Leigh learned of her uncle’s seizure, she became emotionally dysregulated and began to throw sharp items, such as knives and forks, at her infant sibling. As her parents unsuccessfully attempted redirection, she ran outside toward oncoming traffic. Her mother, while being kicked, punched, screamed at, and bitten, tackled her to the ground to contain her. Leigh’s father called for emergency services, and in the presence of three police officers with a dog, Leigh continued her assaultive behavior, with no signs of intimidation or deviation from her escalating demeanor. She was physically restrained and transported to the nearby hospital.

A few hours later, she was medically cleared and transferred to the child and adolescent psychiatry inpatient crisis unit for further evaluation and management. In brief, she was admitted with an intake note describing "normal vital signs…afebrile…positive UA [urinalysis] with dysuria and frequency" and directions to "empirically treat UTI" by continuing a 5-day course of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. She was also prescribed a corticosteroid cream for "eczematous, vesiculopapular skin eruptions" covering widespread surfaces of her arms, legs, and trunk and a moisturizing ointment for "atopic cheilitis" of scaling, fissuring, and peeling around her lips and mouth.

Per history from the patient and her parents, the urinary, skin, and mood symptoms arose 1 week prior. However, they added that Leigh had been performing poorly in school for the past several weeks, receiving multiple disciplinary actions. She was reportedly unwilling to participate in group projects or cooperate with others and was frequently interruptive, restless, impulsive, and distracted—all deviations from the previously well-adjusted, well-mannered, high-achieving girl that began the school year less than 3 months ago and without any past disciplinary or behavioral issues. Over the past few weeks she adopted a disregard for hygiene, avoiding bathing and brushing her teeth and experiencing urinary incontinence. Moreover, these dysfunctional habits translated socially and to her extracurriculars activities; she previously held competitive leadership positions on recreational basketball and soccer teams. Now she engaged in repeated episodes of outbursts, dangerous plays, and fits of rage toward players, coaches, and referees that warranted sanctions, penalties, and expulsions, in addition to concern for the safety of both herself and other children.

Our evaluations of Leigh included one-on-one monitoring, and we also observed her interactions with other patients in the milieu, engaging in various forms of play, and during mealtimes. She was initially difficult to engage with and barely participated in an examination. She was not responding to internal stimuli and denied any misperceptions or hallucinations; her thought process was otherwise logical and linear. There was a paucity in her speech, and she appeared sad, with a constricted range. After 1 day, she was found to frequently interrupt and bully other patients both verbally and physically and displayed a lack of motivation to partake in personal hygiene. She objected to daily showers or baths, to brushing her teeth or hair, and even to wearing clothes and using utensils for meals. She opposed almost reflexively any request to engage in these hygienic activities, and she appeared to lash out for attention and when she wanted something.

Leigh’s stay on the unit lasted 7 days, and psychopharmacologic interventions for aggression, irritability, hyperactivity, impulsivity, and mood instability included aripiprazole 5 mg once daily and methylphenidate 10 mg twice daily. Preliminary impressions included attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) hyperactive-impulsive subtype and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD). Although apprehensive and resistant at first, she agreed to take the medications with encouragement from her parents, and daily play and psychotherapy sessions were aimed at teaching grounding techniques, reframing, and other somatic management skills. By the third day of treatment, she showed stability in her mood and was able to cooperate with others and in psychotherapy sessions. After another day, she demonstrated interest in her personal hygiene and cleanliness and was more easily redirected when her affect escalated. Subjectively, she was feeling more "like herself," as she put it, and displayed remorse and regret at "hurting" loved ones. Her parents corroborated her behavioral improvements. By the fifth day of her hospitalization, her symptoms of rash and UTI were adequately treated after the course of antibiotics and topicals was completed. Regarding her psychiatric improvements, on more than one occasion she was able to ground herself and deescalate from a destructive episode that was brewing. Her response to behavioral therapy and psychopharmacologic management was markedly positive, and she was discharged to home 7 days after admission. Her parents agreed to continue her medication and therapy regimen outpatient.

Discussion

A 9-year-old girl presented to an inpatient child psychiatric crisis unit for new and abrupt onset of aggression, irritability, violence, and impulsivity, among other self-destructive and dangerous behaviors. She was noted to suffer from a UTI, widespread atopic dermatitis, and scaling of her buccal surfaces. The goal in an acute crisis unit is not to pinpoint a single psychiatric diagnosis but rather to treat symptoms that are present and, once a plan is agreed on, to stabilize the patient behaviorally for continued long-term management. The patient’s working diagnosis at that time included ADHD and ODD, but it became paramount to consider the timeliness of her peripheral infections in the context of her neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS) is an overarching condition that includes several contiguous entities, including PANDAS, that points to an underlying infection as a trigger for behavioral changes. Although PANDAS is associated with obsessive-compulsive tendencies and restrictive eating disorder, many more syndromes are being classified along a spectrum of maladaptive behaviors (

4,

5). Recently, Calaprice and colleagues (

6) noted that in roughly half of all PANS cases no identifiable infectious etiology was detected. They described a systematic, qualitative review of features in over 650 cases in which it was found that predominating syndromic characteristics included ADHD, sensory integration disorder, learning disabilities, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. In a post hoc analysis, the following were also typical comorbidities accompanying the presenting neuropsychiatric symptoms: mood lability, irritability, and rage/meltdowns, especially in the context of frequent or chronic infections, such as sinusitis, allergies, eczema, sore throats, headaches, ear infections, urinary frequency, and unexplained rashes and bumps. Moreover, in up to half of all cases, relapses were reported in neuropsychiatric symptoms that did not appear to occur in the setting of a known infection and that clinicians were unable to reliably correlate with a trigger (

6–

8).

When clinicians are presented with an immunologically triggered case, treatment efforts are directed in a multipronged approach, by which the appropriate antimicrobial is prescribed alongside psychopharmacologic interventions. Once symptoms are controlled and infection has cleared, continued psychopharmacologic management, along with psychotherapy, is recommended for continued monitoring. For instance, in classic cases of PANDAS, a 5-day course of azithromycin (or a range or other appropriate antistreptococcal regimens) is prescribed, alongside fluoxetine to continue for 6 months combined with psychotherapy (

8–

10). This paradigm is being explored and is now being tailored and applied to a range of other syndromes.

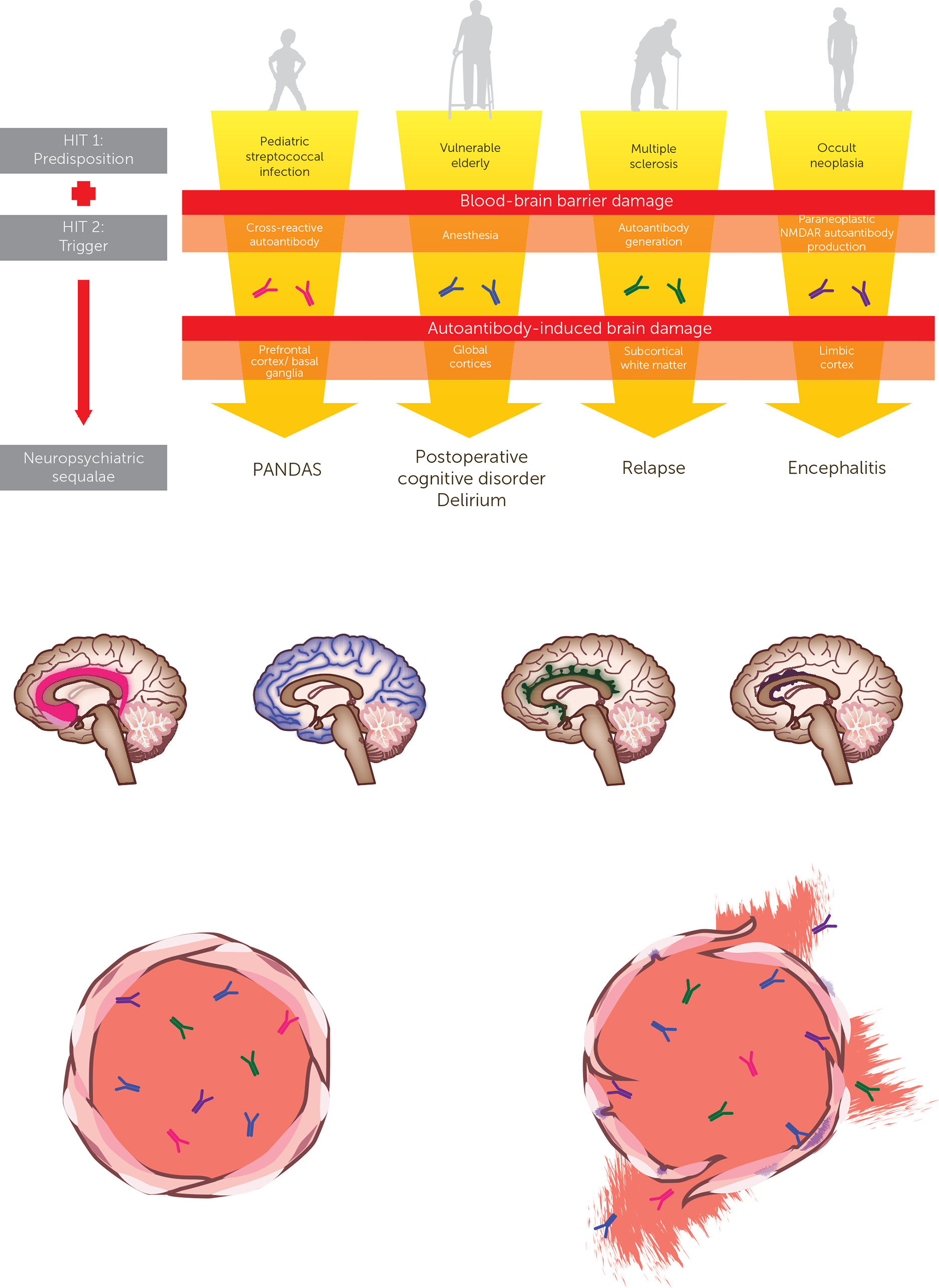

Our case does not fit a diagnosis of PANS, because the patient did not have an eating disorder or obsessive-compulsive tendencies. However, the objective here is to highlight an instance that fits the growing conceptualization of how the immune system may trigger a neuropsychiatric presentation. Outlined in

Figure 1 is a schematic representing the pathophysiologic mechanisms that thread together much of the neuropsychiatric and immunologic components across this continuum. As an inflammatory process takes hold, local permeabilizations occur in the blood-brain barrier, and an influx of self-reactive autoantibodies (thought to belong to a subset of autoantibodies called "natural autoantibodies" that are responsible for cleaning up cell debris made daily in healthy individuals) influence central processes in a broadening array of theorized neuro- and psychopathologies. The realm of autoimmune contributions to pathology of the brain and mind have grown beyond schizophrenia, psychosis, epilepsy, neurocognitive disorder, delirium, depression, and other disorders (

9–

12).