Antidepressants are among the most frequently prescribed medications in the United States across the life cycle, and their use has been increasing in recent years

(1,

2). Elderly patients are substantial users of medication of all types, including antidepressants

(3–

7). During 1995, an estimated 12 million visits were made to office-based physicians by individuals aged 65 years and older during which psychotropic drugs were prescribed. Antidepressants were prescribed at 55% of these visits

(8). The correlates of antidepressant use are critical to determine because depression continues as a major cause of morbidity in elderly populations and antidepressants have been demonstrated in numerous studies to effectively reduce the symptoms of depression in late life

(9).

Although major depression is estimated to be less frequent in later life compared to mid-life (1%–3% versus 3%–5%, respectively), the symptoms of depression are as frequent in elderly individuals as at other stages of the life cycle (10%–15%)

(9–

11). Although older adults are less likely than younger adults to be treated for psychiatric disorders by specialty care providers, they receive a higher-than-expected proportion of antidepressant medication prescriptions from primary care providers

(12,

13). In 1985, of the 21 million visits during which antidepressants were prescribed, 9 million were for individuals 55 years of age and older. Most prescriptions are not written for patients with diagnosed major depression but for those with less severe yet perhaps clinically relevant depression

(14,

15). Therefore, the symptoms of depression are frequent in late life, and antidepressant use is frequent as well.

Medication use in general is lower for African Americans than for whites and is lower for the use of antidepressants

(7,

16,

17). Yet the reasons for this lower use have not been investigated. One reason for the lower use may be a lower prevalence of depression in African Americans than in whites. Most investigators, however, find few differences in either the symptom frequency or the diagnostic frequency of major depression between African American and white older adults, even before adjustment of control factors such as income and education. Berkman et al.

(18) found that 16% of both African Americans and whites in an urban community scored above the threshold for clinically significant depressive symptoms on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D Scale). Weissman et al.

(10), reporting results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study, found the 1-month prevalence of major depression for African Americans to be 3.3% and 3.7% for whites. Prevalence for both African Americans and whites was lower in late life (approximately 1%) but did not vary by race

(10). There are also minimal overall differences in the frequency of depressive symptoms between African Americans and whites

(19). African American elders, however, may be more likely to delay treatment for depression, according to Zubenko et al.

(20). Nevertheless, once they seek treatment, they may actually be more responsive than whites.

We therefore explored the use of antidepressant medications in a cohort of older adults (65 years of age and older) residing in five counties of North Carolina by race and depressive symptoms over a 10-year period (the Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly Duke sample)

(9,

21). This cohort was followed for 10 years, and medication-use data were obtained on four occasions. The following hypotheses were tested: 1) antidepressant use is lower in African Americans than in whites; 2) these differences will persist for all ages and over the 10 years of the survey; 3) the introduction of new-generation antidepressants about midway through the study will increase the use of antidepressants at all ages and for both races; and 4) the racial differences in antidepressant use will persist independent of socioeconomic status, health care access, and other control variables.

Method

Sample

Data for this study were derived from the Duke Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly, part of a multicenter, collaborative epidemiologic investigation of physical, psychological, and social function of individuals aged 65 years and older living in East Boston, Mass.; Iowa and Washington counties, Iowa; New Haven, Connecticut; and the north-central Piedmont region of North Carolina

(9,

21,

22). The North Carolina sample consisted of community residents selected from five contiguous Piedmont counties (one of which was predominantly urban and the other four predominantly rural). The proportion of African Americans in the populations of the five counties was high, ranging from one-third in the urban county to two-thirds in one of the rural counties at the time of the 1980 census. (Less than 1% of the persons interviewed were neither African American nor white.) The Duke Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly is a 10-year prospective cohort study with a baseline interview conducted in 1986–1987 and three additional in-person contacts with sample members in 1989–1990, 1992–1993, and 1996–1997 (P1–P4). Telephone follow-ups were conducted in 1987–1988, 1988–1989, 1990–1991, and 1991–1992 (T1–T4).

The study design has been presented in detail elsewhere

(9,

21). A four-stage stratified household sampling design was used to select a probability sample of 4,162 community residents 65 years old and older. The age range at baseline was 65–105 years. Two-thirds of the participants were women. To enhance statistical precision for estimating racial differences, African Americans were oversampled (by oversampling census blocks with predominantly African American residents) and constituted 53% of study respondents. Of the respondents, nearly one-half lived in the area defined as rural by the U.S. Census Bureau. All levels of socioeconomic status were represented among both African American and white sample members. The manner of sample selection allowed the development of weights that took into account race, gender, age group, number of older persons in the household, location of residence, and lack of response. All procedures were explained to subjects, and written consent was obtained. The procedure for obtaining written informed consent was approved by Duke University Medical Center’s institutional review board and the U.S. Office of Management and Budget.

Data Collection

At baseline and again at each of the three in person follow-up interviews, trained interviewers visited the homes of sample members and used comprehensive structured questionnaires to gather information. For participants too ill or unable to provide information, an appropriate proxy (the person most familiar with the participant) was asked to respond to a subset of objective interview questions. Demographic factors were represented by dichotomous variables for age (65–74 years versus 75 years or more), race, gender, and education (11 years or more versus fewer than 11 years). Self-reported morbidity data (not available from proxy interviews) included multiple aspects of the participants’ physical, social, and mental function, including CES-D Scale scores

(23). All questions on the original CES-D Scale were included verbatim. However, response options were collapsed to a yes-or-no format for reporting the presence or absence of a symptom during the week preceding the interview. The correspondence of CES-D Scale scores determined by the usual method of scoring and by this modified approach is very high

(9). Cognitive status was determined by the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire

(24). Health status was determined by an index of chronic illnesses

(25). Perceived health was assessed by self-report (excellent, good, fair, or poor). Physical disability was assessed by using items from an instrumental activities-of-daily-living scale, a modified Katz Activities of Daily Living Scale

(26), and the Rosow-Breslau physical health scale

(27). Participants were asked about both general outpatient health care and specialty mental health services, as well as supplemental health insurance plans for the elderly, in addition to Medicare. Virtually all supplemental plans for the elderly pay some portion of the cost of medications, although the amount may be very limited

(28). Therefore, if subjects had supplemental insurance, for the purposes of these analyses, they were considered covered. If subjects only had Medicare, medications were not considered covered.

Medication Data Collection and Entry

As part of the interview, participants were asked whether they had taken any medicines prescribed by a doctor or any other medicines obtained from a store during the previous 2 weeks. If they responded “yes,” the participants were asked to show the interviewer these medications

(7,

29). The interviewer recorded the drug name, dose form, and number of dose forms the respondent reported taking the previous day. For prescription drugs, the interviewer also recorded from the label the drug strength, whether the participant’s name was on the label, and whether the medicine was prescribed to be taken regularly or as needed. Details documenting the accuracy of medication data collection, entry, and management have been published elsewhere

(7).

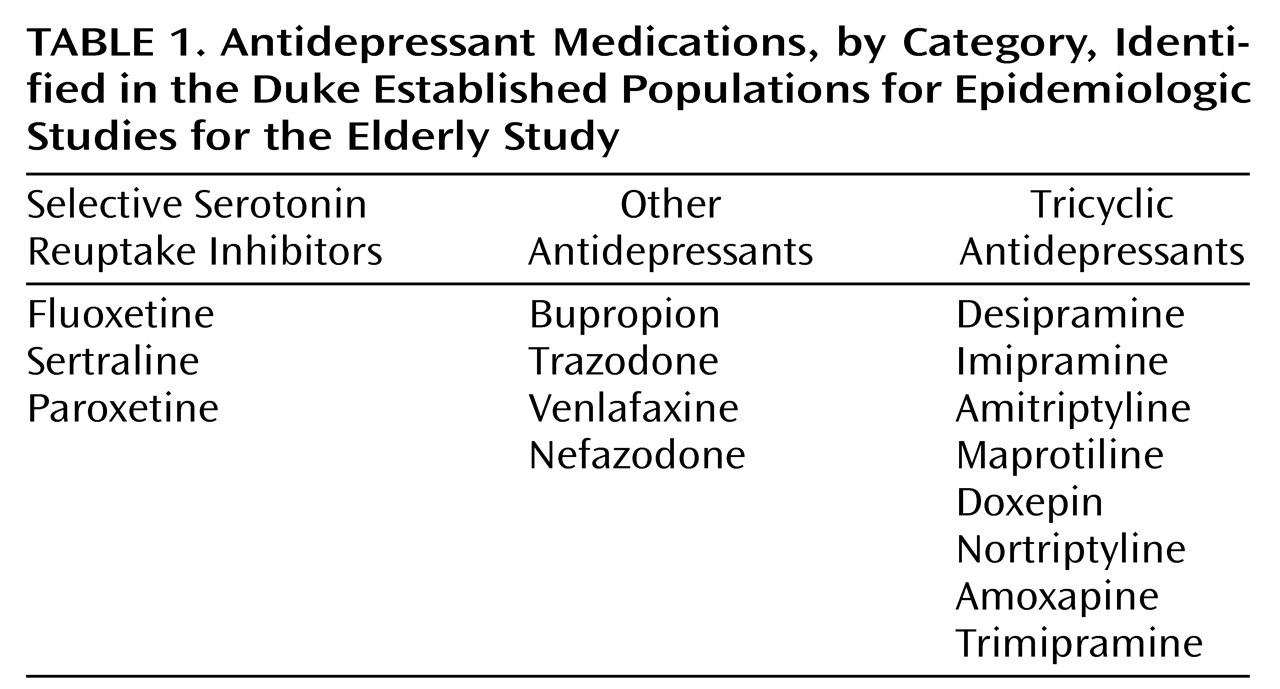

For this study, data from each in-person interview (P1–P4) were analyzed as four cross-sectional studies of the same cohort over the 10 years of the study. The numbers of subjects included at each wave were 4,162 at P1, 3,256 at P2, 2,448 at P3, and 1,640 at P4, including proxy interviews. (Proxy interviews were included in the analyses for those variables where data were available.) Antidepressants were categorized as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants, and “Other Antidepressants” (

Table 1). Monoamine oxidase inhibitors, stimulants, and lithium were not included in the analysis because of the very low frequency of use in this sample (<0.1%). Use of antidepressants was determined from computerized files of participants’ prescription drug data coded with an updated and modified version of the Drug Product Information Coding System

(7,

30,

31). The individual participant was the unit of analysis.

Statistical Analyses

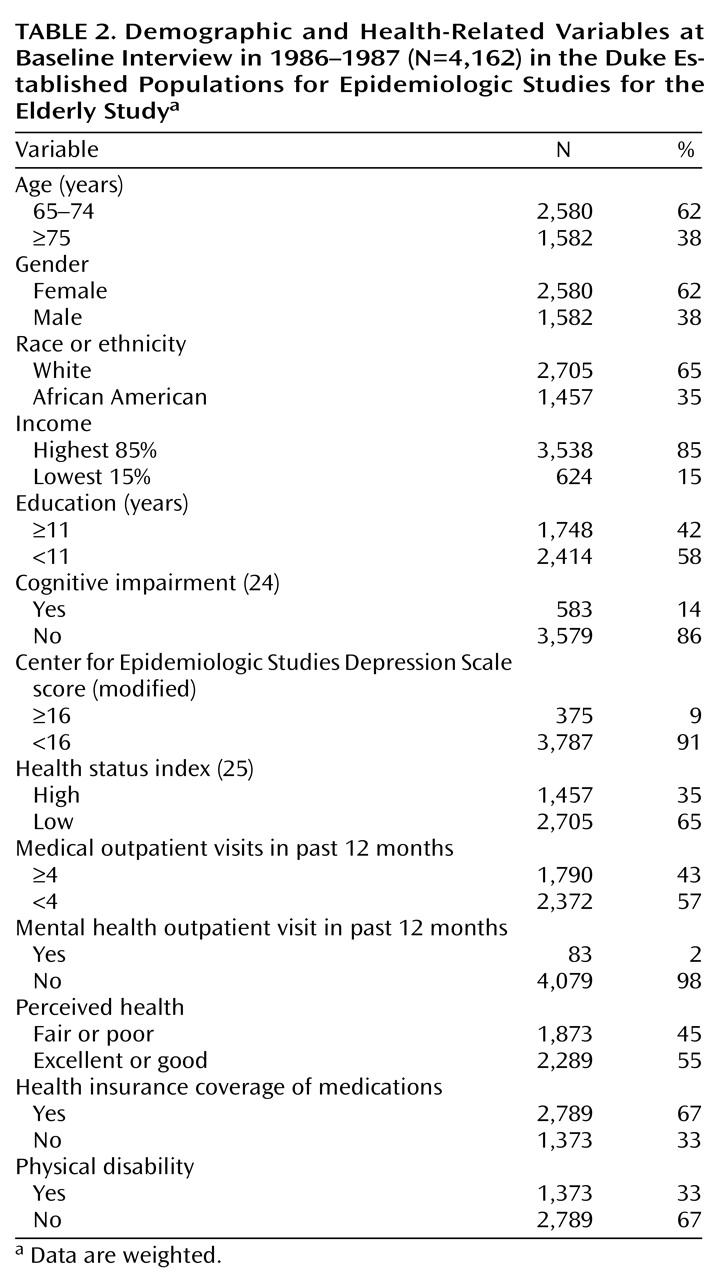

All data were weighted to adjust for the sampling design and to allow inference to the five-county area. The analyses proceeded in three phases. In the first phase, the data were summarized by means of percentages for all covariates at P1 (

Table 2). Odds ratios of antidepressant use, weighted but unadjusted for other covariates, were calculated for all covariates at P1. Next, the frequency of antidepressant use by race and age were calculated for each P1–P4 group by category of antidepressant use. Finally, logistic regression was used to estimate the effects of the independent variables on dichotomous variable use versus no use of any antidepressant medication for each interview wave. All variables were entered in the regression analysis, although not in a stepwise manner.

Results

The antidepressant medications mentioned by respondents at least once during the four in-person interviews are listed in

Table 1 by category. The distributions of selected variables used in these analyses at the baseline interview (1986–1987) are presented in

Table 2. These and all tables present weighted data arrived at by applying the sample weights to the sample. For example, the 53% of African Americans included in the sample were weighted to the proportion of African American elders in the population of the five counties (35%).

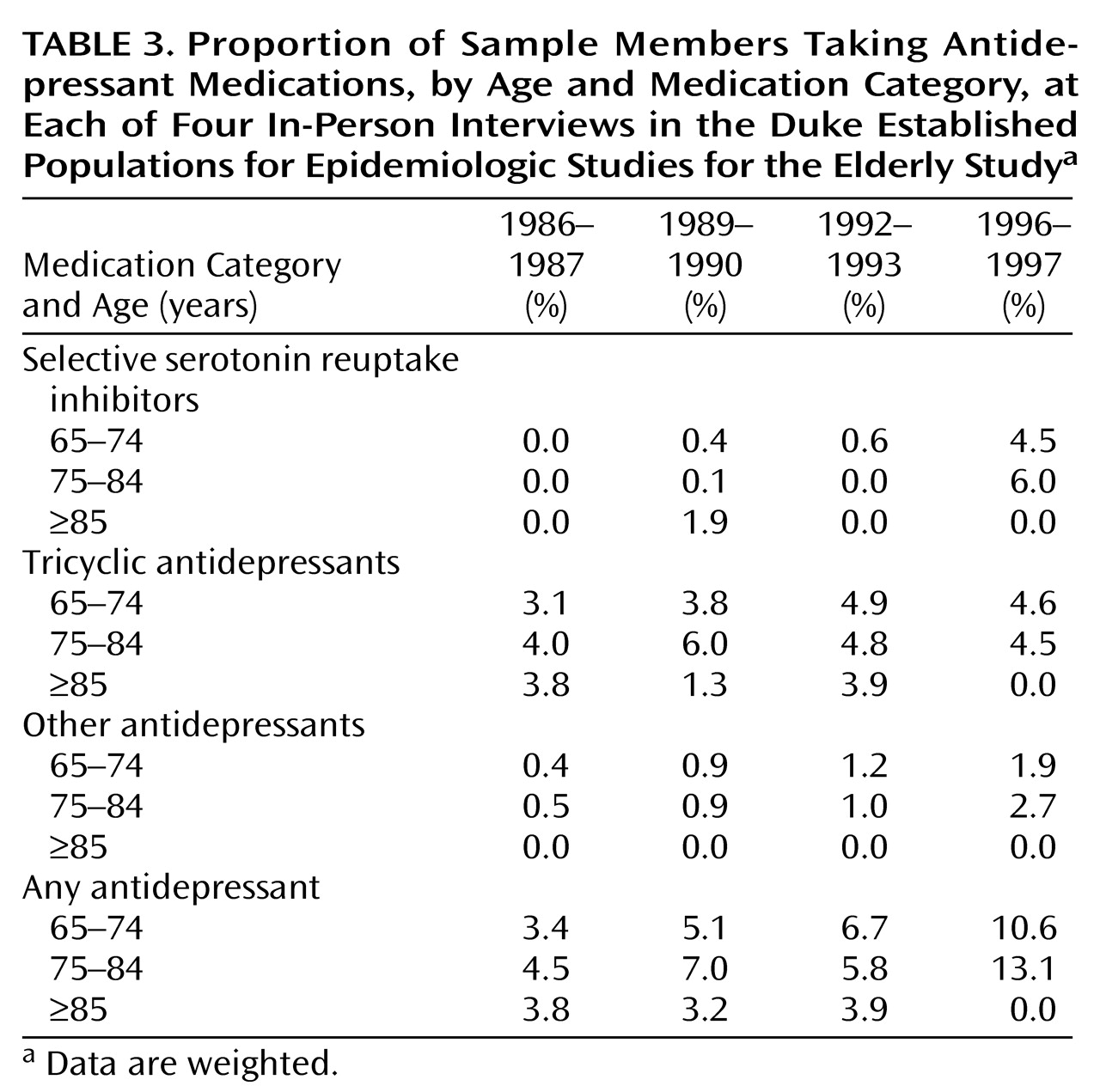

For the entire sample, the proportion of subjects taking antidepressants increased from 3.8% in 1986–1987 to 11.0% in 1996–1997. In

Table 3, the proportions of sample members taking antidepressant medications by baseline age at each of the four in-person interviews by drug category are presented. The 65–74 age group in 1986–1987 was therefore 75–84 in 1996–1997. No subjects 95 years old and older were taking antidepressant medications in 1996–1997. Otherwise, antidepressant use increased for the 65–74 and the 75–84 age cohorts throughout the 10 years of follow-up. The introduction of fluoxetine in 1988 and four additional antidepressants since appears to be a major contributor to the increased use of antidepressants, although their introduction does not appear to have led to a decrease in the use of tricyclic antidepressants except in the oldest old.

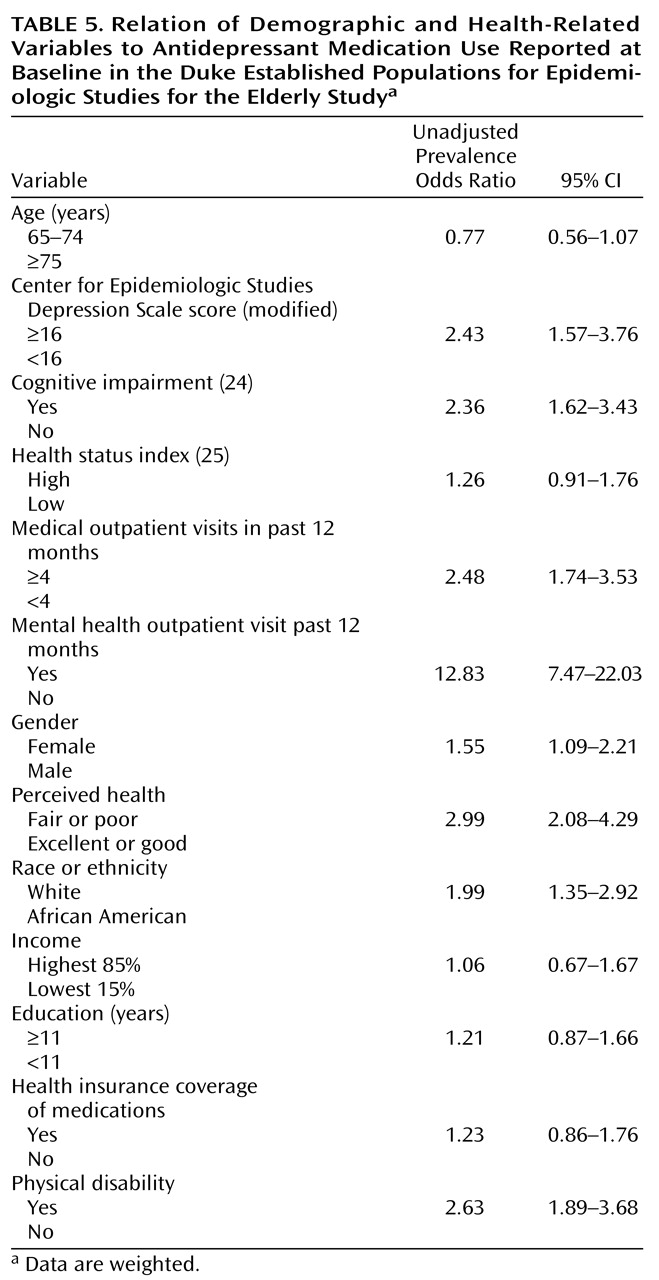

In

Table 5, unadjusted prevalence odds ratios of antidepressant medication use at the time of the baseline interview are presented by selected exposure variables. As would be expected, higher scores on the CES-D Scale, higher number of outpatient medical visits, and visit to a mental health professional in the past 12 months were strongly associated with antidepressant use. The number of subjects who visited a mental health professional at each in-person interview, however, was <3%. In addition, physical disability, perceived health, cognitive impairment, female gender, and white race were correlates. These variables were therefore explored as correlates of antidepressant use for each of the four in-person interviews. (No longitudinal analyses were undertaken.)

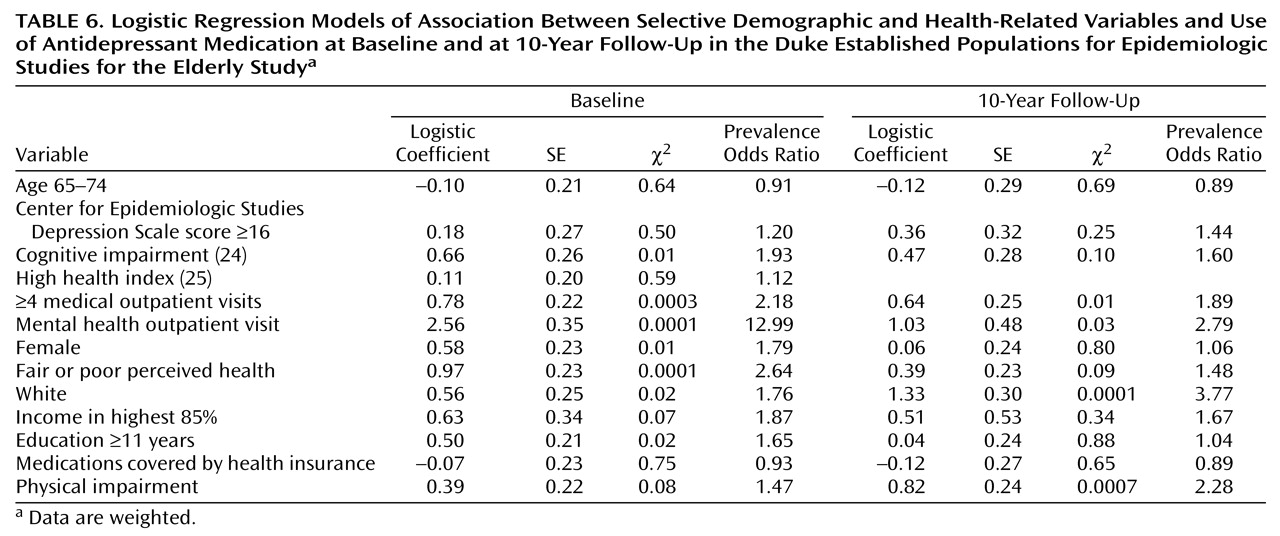

Results of the logistic regression model of association between selected factors and antidepressant medication use in 1986–1987 and 1996–1997 are presented in

Table 6. Significant correlates (p<0.05) at both interviews were four or more medical outpatient visits in the past year, mental health outpatient visit, and white race. The prevalence odds ratio at baseline in these controlled analyses for race approached 2 in 1986–1987 and 4 in 1996–1997. Of interest, CES-D Scale scores, female gender, and medication coverage by health insurance were not significantly associated with antidepressant use.

Conclusions

The major findings from this analysis are the significant increase in antidepressant use despite the increasing age of the cohort and the marked differences in antidepressant use between whites and African Americans. In 1986–1987 whites were twice as likely to take antidepressants as African Americans, and this variance increased to nearly a threefold difference by 1996–1997. Although African Americans in this cohort doubled their use over 10 years, whites tripled their use. All four original hypotheses were confirmed. Most of this increase in antidepressant use was secondary to the increased use of SSRIs. The odds ratio for race was higher than for any other variable in the controlled analyses at the 10-year follow-up.

Other variables associated with antidepressant drug use at the time of each of the in-person interviews included cognitive impairment (at baseline only), use of health and mental health outpatient services, female gender (highly significant at the baseline interview but virtually absent at the 10-year follow–up), poor perceived health (highly significant at baseline but no longer significant at the 10-year follow-up), and impaired physical function (not significant at baseline but highly significant at the 10-year follow-up). CES-D Scale scores were not a significant correlate at either baseline or the 10-year follow-up. This may be the result of the effectiveness of the medications, but it also may be a result of the drugs not being prescribed appropriately. The CES-D Scale is a screening instrument, and although it correlates significantly with clinical diagnoses of depression, it is not analogous to a clinical diagnosis.

How can this marked difference in antidepressant use by race be explained? First, it is unlikely, given the technique for assessing drug use, that African American elders are less likely to report the use of medications than white elders. In addition, there is no evidence that African Americans who refused participation in the study were more likely to be taking antidepressant medications than whites. The results, however, may reflect the unique geographic characteristics of North Carolina and may not be generalized to all populations of African Americans and whites in the United States. In this sample, African Americans were more likely to receive their care at a hospital than from a usual provider in the community

(32). They also were more likely to put off all health care because of cost, despite the virtual universal coverage of health care by Medicare

(32). Medicare does not pay for medications.

Previous reports by our group have documented that drug use patterns overall differ by race in this elderly community sample. African Americans were less likely to use over-the-counter medications (66% versus 76%, respectively) and total medications (88% versus 92%) than whites

(7). The greatest differences were for psychotropic medications (14% versus 26%) and nutritional supplements (17% versus 28%). The differences were 23% versus 29% for gastrointestinal drugs and 56% versus 63% for analgesics

(7). Race explained only 6% of the overall variance for differences in the use of prescription drugs, with health insurance and use of medical services the strongest predictors of prescription drug use for both races. Given that health insurance and use of outpatient medical services were controlled in the current study, the differences by race, especially the increased differences over time, are significant.

One explanation for the differences in use by race may be that African Americans may not report symptoms of depression as frequently as whites. In a previous report by our group, African American elders reported fewer sleep complaints, but this difference was more pronounced for some complaints, such as a “wakeful sleep” than for others, such as trouble falling asleep

(33). Yet the frequency of reported symptoms and patterns of responses to CES-D Scale questions do not appear to vary significantly by race in this sample

(19). In addition, in controlled analyses, the frequency of major depression appears to be similar for African Americans and whites

(10).

Perhaps the most striking factor is the discrepancy of reported use of the new-generation antidepressants by race in this sample, especially the SSRIs. In 1996–1997 there was nearly an eightfold difference in the use of these medications by race in uncontrolled analyses. Even when controlling for health coverage of medications and income, it appears that African Americans are significantly less likely to be prescribed these medications. The dramatic changes in the patterns of antidepressant prescribing in outpatient practices documented by Pincus et al.

(2) appear to be reflected in the prescriptions to white but not to African American elders. The most likely explanation is that physicians are more likely to prescribe SSRIs to whites than to African Americans. Previous reports have documented that African Americans are more likely to receive tricyclic antidepressants than SSRIs in the 18–64 age group

(34). Because no evidence exists to suggest that SSRIs are less effective in African American elders and there is a significant reduction in side effects with SSRIs than with tricyclic antidepressants, the differential prescribing patterns probably reflect a combination of relative underdiagnosis of a treatable condition in elderly African Americans, coupled with prescribing practices in part determined by the race of the patient. Educational programs could correct in part these problems once they are identified among individual practitioners and within practice plans.