Both substance abuse and pathological gambling have been considered addictive disorders or disorders of impulse control

(1–

3). Similarities include progressive loss of control over the behavior, preoccupation with the behavior, seeking of a euphoric state or “high,” presence of craving, development of tolerance, withdrawal symptoms, increased activity during times of stress or depression, and continuation of the behavior despite adverse consequences

(4). In addition, it has been suggested that these disorders have a common genetic component

(5).

The rate of comorbidity of substance abuse (excluding tobacco) and pathological gambling varies, depending on the primary disorder being studied. Rates of 34%–80% for substance use disorders have been reported among pathological gamblers in treatment, with much of this contributed by alcoholism diagnoses

(6–

10). In two studies

(6,

9) there were substantially lower rates of drug diagnoses (6% and 4%) than of alcoholism diagnoses (34% and 32%). Rates of 5%–21% for pathological gambling have been reported among substance abusers in treatment

(11–

20), and one inpatient study had a rate of 33%

(21). These rates are at least three times as high as the occurrence rate of pathological gambling in the general population

(22), further suggesting some common factor in the two disorders.

There remain major gaps in our knowledge of comorbid pathological gambling among substance abusers. Most published reports have presented data on patients who were abusing a variety of substances, although there is some evidence that the occurrence of pathological gambling may vary by primary substance of abuse

(6,

15,

17,

23). To our knowledge, no published study has used a structured diagnostic interview to diagnose pathological gambling by established diagnostic criteria. One study

(20) supplemented the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Lifetime Version (SADS-L) with questions based on DSM-III-R criteria for the diagnosis of pathological gambling. Another study

(15) used questions based on the DSM-III criteria for pathological gambling. All of the other published studies we know about have used a screening instrument (South Oaks Gambling Screen). We know of no study that distinguished between lifetime and current pathological gambling or evaluated the temporal relationship between onset of substance abuse and onset of pathological gambling.

Few studies have addressed the influence of pathological gambling on the outcome of substance abuse treatment. One published study

(20) showed no significant difference in 1-year outcome (as shown by ratings of problem severity on the Addiction Severity Index) by lifetime diagnosis of pathological gambling in 93 cocaine-dependent patients receiving either inpatient or outpatient treatment. In another published study of 154 inpatient substance abusers

(11), a lifetime history of pathological gambling (by South Oaks Gambling Screen) had no significant influence on housing or employment status at 6-month follow-up (substance use status was not reported). In a recent study

(24) of 386 methadone-maintained outpatients followed up after 9 months, those considered to have a “highly successful” outcome had significantly lower scores on the South Oaks Gambling Screen than did patients with less successful outcomes.

In the present study we evaluated pathological gambling in a relatively homogeneous group of 313 currently cocaine-dependent outpatients (200 also with current opiate dependence), using a structured diagnostic interview to generate DSM-III-R diagnoses and objective measures of treatment outcome (urine toxicology results, length of stay in treatment). Three main questions were addressed: l) What is the occurrence of pathological gambling and its temporal relationship to cocaine dependence? 2) How do the characteristics of patients with pathological gambling compare with those of patients without pathological gambling? 3) What is the influence of pathologic gambling on the short-term outcome of treatment for cocaine dependence?

Results

Occurrence of Pathological Gambling

The overall occurrence rate of lifetime pathological gambling in these 313 cocaine-dependent outpatients was 8.0% (N=25): 6.2% (N=7) among those with cocaine dependence only and 9.0% (N=18) among those with both cocaine and opiate dependence. One-half (48.0%) of the pathological gamblers reported current (within past month) gambling behavior (N=12), while 40.0% (N=10) reported no such behavior in more than a year.

Patient Characteristics

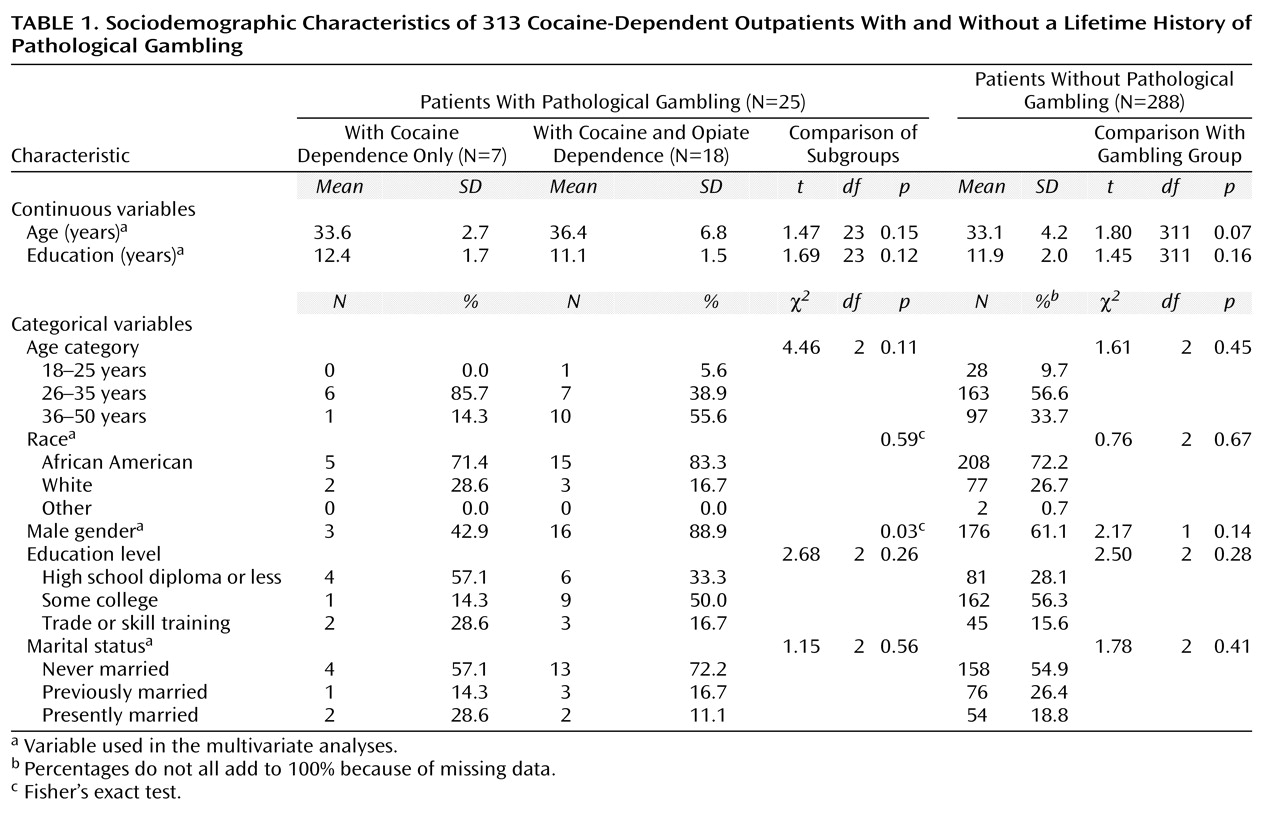

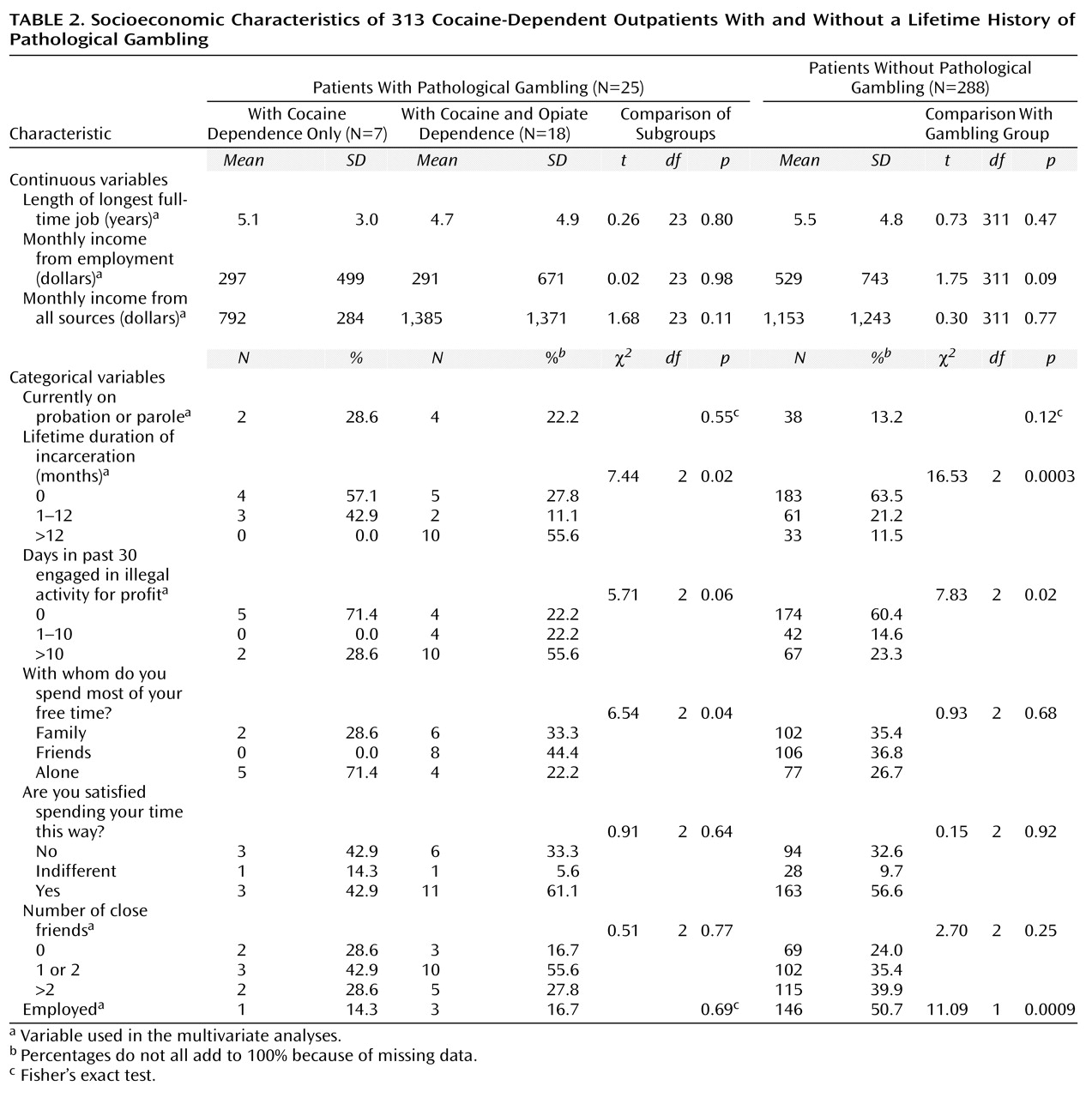

The patients with pathological gambling differed in sociodemographic and socioeconomic characteristics from those without pathological gambling only in that they were less likely to be currently employed, were more likely to have recently engaged in illegal activity for profit, and had a longer duration of lifetime incarceration (

Table 1 and

Table 2). These differences derived primarily from the patients with dual cocaine and opiate dependence. These pathological gamblers also differed from those with only cocaine dependence in being more likely to be male (

Table 1) and to spend their free time with friends (

Table 2). The stepwise logistic analysis yielded results similar to those from the univariate comparisons. Only history of antisocial personality disorder and lifetime duration of incarceration contributed significantly to the correct classification of subjects by history of pathological gambling. These two variables correctly classified 68.4% of the subjects, incorrectly classified 15.3%, and left 16.4% indeterminate.

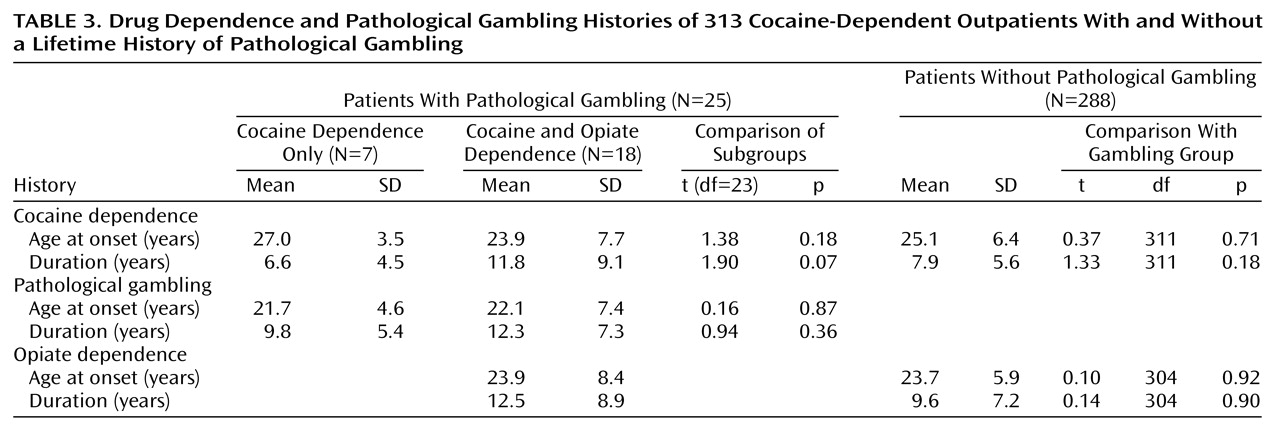

The patients with pathological gambling did not differ significantly from the other subjects in age at onset of cocaine or opiate dependence or duration of dependence (

Table 3). However, the pathological gamblers with opiate dependence did show a nonsignificantly longer duration of cocaine dependence than those without opiate dependence (

Table 3). The onset of pathological gambling preceded the onset of cocaine dependence in 18 (72.0%) of the subjects, came afterwards in six (24.0%), and was within the same year for one (4.0%). Age, sex, marital status, and employment status did not differ significantly by order of onsets (data not shown). Among the 18 opiate-dependent pathological gamblers, the onset of pathological gambling preceded the onset of opiate dependency in eight (44.4%), came afterward in seven (38.9%), and was within the same year for three (16.7%). For only one patient did the onset of gambling come between the onsets of cocaine and opiate dependence.

The rates of most other DSM-III-R axis I psychiatric disorders were not significantly different in the patients with and without pathological gambling. The respective rates of depression were 8.0% (N=2) and 4.9% (N=14) (χ2=0.45, df=1, p=0.38), the rates of posttraumatic stress disorder were 12.0% (N=3) and 4.9% (N=14) (χ2=2.28, df=1, p=0.15), and the rates of phobias were 24.0% (N=6) and 22.9% (N=66) (χ2=0.02, df=1, p=0.89). However, tobacco dependence was more common among the pathological gamblers: 84.0% (N=21) versus 61.1% (N=176) (χ2=5.17, df=1, p=0.02). Also, there was a significantly higher occurrence of antisocial personality disorder among the pathological gamblers (56.0%, N=14) than among the other subjects (19.8%, N=57) (χ2=16.87, df=1, p<0.0001).

Treatment Outcome

The patients with and without pathological gambling did not differ significantly in either mean length of stay (60.4% versus 59.8% of possible maximum length of stay) (χ2=0.00, df=1, p=0.94) or mean proportion of urine samples positive for cocaine (44.0% versus 36.8%) (χ2=0.91, df=1, p=0.59). This was also the case when we considered only the 12 outpatients who had current (within the past month) pathological gambling: the mean lengths of stay for the patients with and without pathological gambling were 64.1% and 59.6% (χ2=0.08, df=1, p=0.78), and the mean rates of cocaine-positive urine tests were 42.6% and 37.2% (χ2=0.18, df=1, p=0.67). Among the 200 opiate-dependent outpatients, those with and without pathological gambling did not differ significantly in mean proportion of urine samples positive for opiates (45.5% versus 31.8%) (χ2=1.14, df=1, p=0.27). As in the univariate comparisons, lifetime history of pathological gambling did not contribute significantly to the prediction of either outcome variable. In the final stepwise multiple linear regression models, its F-to-enter was 1.86 (p=0.17) for predicting length of stay and 0.03 (p=0.86) for predicting percentage of cocaine-positive urine samples.

Discussion

In this study of 313 cocaine-dependent outpatients in treatment, we found an 8.0% occurrence rate of lifetime pathological gambling (DSM-III-R criteria), and the rates were similar in the two subgroups: 9.0% in those with and 6.2% in those without concurrent opiate dependence. The overall rate is five times as high as the reported occurrence rate of 1.5% in the general population of Maryland

(22), the state where this research was conducted, but within the 5%–21% range reported for substance abusers in outpatient treatment

(11–

13,

17–

19) and the 7%–15% range reported for patients receiving treatment for primary cocaine abuse

(15,

20,

23). These findings support previous recommendations that screening for pathological gambling be part of the intake process for substance abuse treatment programs. Incorporating material on pathological gambling into substance abuse treatment may be preventive for patients who are not pathological gamblers and may lead to better treatment outcome for those who are.

The substantially higher occurrence rate of pathological gambling among cocaine-dependent outpatients than among the general population suggests a possible causal relationship between the two conditions. One possibility is that cocaine use contributes to pathological gambling, e.g., by increasing impulsivity or impairing judgment. This seems unlikely, since the majority of the patients in our study developed pathological gambling before drug dependence, more so for cocaine than for opiates. (This order of onset for the disorders is consistent with findings from a prior study [21], in which inpatients receiving substance abuse treatment reported that they started to gamble before they first used drugs.) Another possibility is that cocaine dependence and pathological gambling have common antecedent factors that promote vulnerability to both disorders or that they represent different conditions along a spectrum of related disorders of impulse control and addiction. This possibility is supported by the finding of similar allelic distributions for several dopamine receptor genes among patients with pathological gambling and substance use disorders, which differ significantly from the distributions found in a healthy comparison population

(5). What might be the antecedent or vulnerability factors linking pathological gambling and substance use disorders remains open to speculation. Psychological studies of pathological gamblers suggest that traits such as sensation seeking, impulsivity, and risk taking may be factors they share with substance abusers

(2,

23,

32,

33).

In this study, cocaine-dependent outpatients with pathological gambling were more likely to be unemployed, had more frequently engaged in recent illegal activity for profit, and had spent more time incarcerated than outpatients without pathological gambling (

Table 2), although the two groups did not differ significantly in several sociodemographic characteristics (

Table 1). This pattern of findings is similar to that of most prior studies that explicitly compared substance abuse patients with and without pathological gambling identified with a screening test (South Oaks Gambling Screen). In particular, in two of three studies greater unemployment among patients with pathological gambling was also found

(13,

14). The one exception, which showed no difference, was a comparison of 12 patients from each group matched on age, gender, and occupation

(34). One prior study

(20), like ours, showed more months of incarceration among pathological gamblers. As in our study, no prior study has shown differences in race or marital status

(12–

14,

20,

21), five of seven showed no difference in gender

(12–

15,

21) (two showed a preponderance of men among pathological gamblers [

19,

20]), and three of four indicated no difference in education level

(13,

14,

20,

21). The one subject characteristic with inconsistent findings is age. In two prior studies there was no difference in age

(13,

21), as in the present study, and in two other studies the pathological gamblers were older

(14,

20).

Previous studies have shown high rates of other DSM axis I psychiatric disorders among treated substance abusers with pathological gambling. For example, Linden et al.

(8) found that 76% of pathological gamblers reported at least one episode of major depression and 52% had a history of either recurrent episodes of major depression or bipolar disorder. We found much lower rates of lifetime psychiatric comorbidity, e.g., an 8.0% occurrence rate of lifetime depression. These low rates are presumably due to the subject eligibility criteria, which excluded subjects with current severe psychiatric symptoms or need for psychiatric treatment.

The present study did indicate a high occurrence rate of antisocial personality disorder, which was significantly higher in the subjects with pathological gambling (56.0% versus 19.8%). This contrasts with a prior finding for cocaine-dependent patients

(20), in a study using a different structured diagnostic interview, the SADS-L. In that study there was a much lower occurrence rate of antisocial personality disorder and no difference between patients with and without pathological gambling (5% versus 8%, respectively). One possible explanation for these different findings is differences in concurrent substance use disorders. The prior study excluded patients with opiate dependence, and about two-thirds of the patients had alcoholism (80% of the pathological gamblers), while about two-thirds of the patients in the present study had opiate dependence, and those with alcohol dependence were excluded.

The presence of lifetime or current (1-month) pathological gambling had no significant influence on outcome during active treatment, whether assessed by retention (length of stay) or proportion of cocaine-positive urine samples. This finding runs counter to the general rule that psychiatric comorbidity is associated with poorer treatment outcome, but it is consistent with a published report of no difference in 1-year drug use outcome between former patients with and without lifetime pathological gambling

(20). The finding is unlikely to be confounded by group differences in subject characteristics known to influence treatment outcome. The subjects with and without pathological gambling were similar in most such characteristics (

Table 1 and

Table 2). Where the groups did differ significantly, the pathological gamblers had more of the characteristics usually associated with poorer treatment outcome, e.g., higher rate of antisocial personality disorder, more unemployment, and greater history of illegal activity (

Table 2).

This study had several methodological strengths. First, formal diagnoses of cocaine dependence and pathological gambling were made with a structured diagnostic instrument (DIS) and established diagnostic criteria (DSM-III-R). Almost all of the other studies used a screening instrument to determine “probable” pathological gambling; only two studies used structured questions and made formal diagnoses

(15,

20). Second, the influence of the diagnosis on (short-term) treatment outcome was assessed. We know of only one prior published study that evaluated drug use as a treatment outcome

(20). Third, age at onset of the disorders was assessed, and lifetime and current pathological gambling were distinguished, allowing a finer look at the chronological aspects of comorbidity. In all of the prior studies, only lifetime diagnoses were reported.

One limitation of this study was the absence of data on the type of gambling in which the subject was involved; therefore, the actual patterns of gambling could not be evaluated. The generalizability of findings is limited by the restricted range of sociodemographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the patients involved and the exclusion of many individuals with other current psychiatric disorders. However, the sociodemographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the subjects were typical of many patients in publicly funded outpatient drug abuse treatment programs.