The

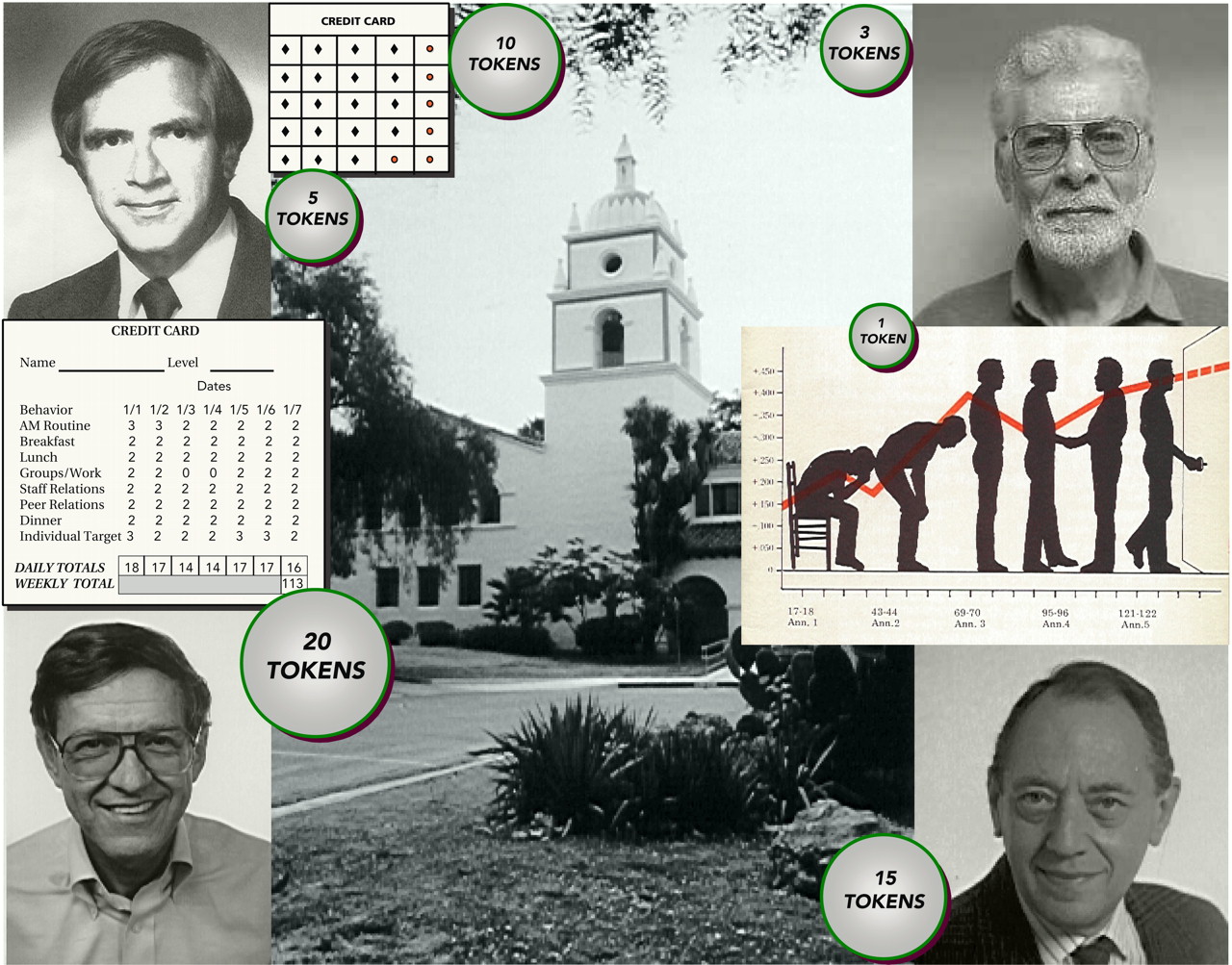

image shows the pioneers of the token economy (clockwise from the top left): Nathan Azrin, Ph.D., Gordon Paul, Ph.D., Leonard Krasner, Ph.D., and Teodoro Ayllon, Ph.D. Sample cards and tokens are depicted, as is the bell tower building of Camarillo State Hospital, Calif., location of the longest-lasting token economy.

More than four decades ago, influenced by the Utopian ideas and operant conditioning principles of the behavioral psychologist B.F. Skinner, pioneering scientist-practitioners designed the token economy to remediate the problems of seriously mentally ill patients who were then residing in large numbers in state and Veterans Administration mental hospitals. In the token economy, the full range of self-care, social, and work behaviors could be modified by systematic and preplanned use of antecedents (e.g., prompts) and consequences (e.g., reinforcers) of these behaviors. The “psychopathological” behavior of the mentally ill was conceptualized as being subject to the same “laws of learning” that influenced normal behavior. Successful demonstrations of operant conditioning applied to the mentally ill, therefore, were the forerunners to the potentialities for “recovery” and “empowerment” in persons with severe mental disorders.

The design of a ward-wide system for organizing the consistent application of antecedents and consequences of behavior was termed the “token economy” because tokens could be conveniently dispensed to patients contingent on their exhibiting improvements in their behavior. The tokens were then subsequently exchanged for a panoply of rewards that were often individually determined by each patient—cigarettes, candy, beverages, personal radios or televisions, single rooms, special privileges and home visits, and other activities or things that were valued and preferred by each patient.

During the 1960s and 1970s, a residual cadre of patients with schizophrenia who responded suboptimally to antipsychotic medications became candidates for the token economy, and these programs expanded exponentially, with 110 of them operating throughout the United States and Western Europe. Controlled research revealed the efficacy of the token economy in a wide variety of settings and for many patient populations, including children in special education classrooms, the mentally retarded, adolescents with conduct disorders in residential care homes, and psychiatric patients in day hospitals.

Despite the evidence-based success of token economies, they failed to follow patients into community facilities during the past three decades of deinstitutionalization. Several reasons accounted for the erosion of the token economy. The concept met with resistance from mental health professionals whose training had emphasized an ideology of intrapsychic and psychodynamic mechanisms to explain abnormal behavior. Training staff to be consistent and positive in their interactions with patients was daunting, and maintaining staff consistency with the quality standards of token economies required intrepid organizational and management skills. The token economy posed challenges to program managers who found the enriched, individualized, and planned environmental design required by this approach to be anathema to cost constraints and bureaucratic inflexibility. Finally, it proved difficult to design programs in open settings and identify “natural reinforcers” in the community that could provide opportunities, encouragement, and rewards to support improved behavior brought about by token or incentive systems. The token economy did spawn more “user friendly” techniques of behavior therapy, which have devolved into the contemporary spectrum of modalities that make up psychiatric rehabilitation.