Disability, as defined in both a legal

(1) and clinical

(2) sense, denotes a level of functional impairment sufficient to impair major life activities. Mental disorders, by definition, must result in either distress or functional impairment; however, all mental disorders do not lead to disability, and, conversely, all disability is not caused by psychiatric conditions

(3). Understanding the prevalence and correlates of disability in patients with mental and general medical illness can be an important first step in improving these individuals’ functional status and quality of life.

As of 1990, chronic illnesses were estimated to account for $659 billion annually in total costs to society

(4). Conditions resulting in disability account for a disproportionate share of those expenditures

(5), particularly during periods of economic growth, when employment rates among the nondisabled are highest

(6). The World Health Organization’s Global Burden of Disease study emphasized the central role of mental disorders in disability, ranking mental disorders second worldwide among categories of illness in overall disease burden

(7).

Beginning with the Medical Outcomes Study, a series of studies has used medical populations to compare functional impairment between patients with mental disorders and general medical conditions. The Medical Outcomes Study has demonstrated that as compared with a set of tracer medical conditions, major depression is associated with comparable overall impairment and uniquely high levels of social and role dysfunction

(8,

9). Other studies have subsequently confirmed these findings for other mental disorders and in a variety of U.S. and international primary care settings

(10–

12).

To understand the nature and impact of mental and general medical disability in the community, at least three basic questions must be addressed. First, at a population level, what is the prevalence of mental and physical disability in the United States? And how commonly do the two forms of disability occur concurrently?

Second, at an individual level, how similar are the deficits seen in mental and physical disability? This question includes both the overall level of impairment and also specific patterns of limitations seen in general medical, mental, and combined conditions.

Finally, at both the individual and population levels, are there social, economic, or workplace factors that exacerbate disability in these disorders? More attention has been paid to the role of such issues as self-labeling, stigma, and discrimination in the sociological than in the medical disability literature

(13). Nonetheless, these factors are of potentially great importance from a health policy perspective. Most notably, the Americans With Disabilities Act cast the issue of disability in a civil rights perspective, providing disabled individuals protection against discrimination in the workplace

(14).

The present study uses data from the largest U.S. disability survey ever conducted to examine the association of mental, physical, and combined conditions with functional disability. The results, derived from nationally representative data, may help further the understanding of the nature and correlates of disability.

Method

National Health Interview Disability Survey

The sample was drawn from respondents to the National Health Interview Disability Survey. The questionnaires were administered as part of the 1994 and 1995 National Health Interview Survey, a complex, multistage probability survey that targeted the noninstitutionalized civilian U.S. population.

The National Health Interview Disability Survey was administered in two phases. The phase 1 questionnaire, administered concurrently with the core National Health Interview Survey, collected basic data on disability, mental conditions and symptoms, and demographic data. The primary screening question determining eligibility for the second phase asked individuals whether they were currently “unable or limited in ability to participate in a major activity, including work and household responsibilities.” The phase 2 questionnaire, administered to individuals from phase 1 with evidence of disability, obtained more extensive information about employment, use of services and benefits, transportation and personal assistance needs, housing characteristics, environmental barriers, and participation in social activities. Response rates were 87% for phase 1 and 89% for phase 2, for an overall response rate of 77%.

Because the definition and potential implications of disability in children and geriatric populations differ substantially from those in working-age adults, we included only respondents age 18–55 for this study. The final sample was composed of all respondents in this age group who completed phases 1 and 2 of the 1994 and 1995 surveys.

Conditions Causing Disability

Each respondent who reported being unable to participate or limited in participating in a major life activity was asked to identify up to two contributory conditions, which were subsequently coded according to ICD-9. Using these responses, we defined four categories for all subsequent analyses:

Mental disability only: ICD-9 codes 290.00–316.99.

General medical disability only: ICD-9 codes other than 290.00–319.99 (individuals with mental retardation, codes 317.00–319.99, were excluded from all analyses).

Mental and general medical disability: both 1 and 2.

No reported disability.

Other Independent Variables

Basic demographic information, including sex, age, race, marital status, education, income, and insurance status, were compared across categories of disability and included as covariates in multivariate analyses.

Dependent Variables

Analyses examined functional limitations, work status, disability payments, and barriers to work reported by each group of respondents.

Functional Limitations

A number of questions relating to functional limitations were included in the questionnaires. Social and physical limitations constitute important and independent aspects of function and disability

(12,

15). Cognitive skills are also essential for finding jobs in an economy that is increasingly based on information

(16). Therefore, social, physical, and cognitive functioning were the three summary domains of functioning used for this study (Cronbach’s alpha scores were subsequently used to confirm each domain’s internal coherence):

Social limitations constituted a report of trouble making or keeping friendships, trouble getting along with people in social situations, or serious difficulty coping with stress (Cronbach’s alpha=0.64).

Cognitive limitations included a report of frequent trouble concentrating, confusion, or forgetfulness (Cronbach’s alpha=0.65).

Physical limitations encompassed problems with activities of daily living, instrumental activities of daily living, or fair or poor health status (Cronbach’s alpha=0.60).

Respondents were asked two other global disability questions that were analyzed separately. First, a question was asked about whether he or she had any days spent at home in bed (home bed days) during the past year. Second, each respondent was asked about others’ perceptions of his or her disability.

Work Status, Disability Payments, and Work Barriers

A series of stem questions assessed current work status. Respondents identified whether they were working (in either a limited or unlimited capacity) or not working (either looking for work or unable to work). A separate section of the interview asked about receipt of Supplemental Security Income (SSI), Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), and work-based disability pensions.

Respondents who were not currently working were asked whether the following financial, social, or workplace barriers were contributing to their inability to work: 1) fear of losing SSI or SSDI payments, 2) fear of losing housing, 3) fear of losing health insurance coverage, 4) family or friends discouraged individual from applying for work, 5) family responsibilities kept individual from seeking employment, 6) inadequate information about jobs, 7) perception that he or she would be unable to advance in the workplace, 8) inadequate job training, and 9) lack of transportation.

Respondents who were currently working were asked a series of questions regarding job discrimination on the basis of their disability. “In the past 5 years, have you been fired from a job, laid off, or told to resign because of an ongoing health problem or disability?” “In the past 5 years, because of an ongoing health problem, impairment, or disability, have you been a) refused employment? b) refused a promotion? c) refused a transfer? d) refused access to training programs? e) unable to advance at work?”

Data Analysis

Bivariate comparisons were used to examine the association between type of disability and functional limitation, work status, and barriers to work. Confidence intervals (CIs) of 95% were generated to allow comparisons across cohorts with mental, physical, and combined conditions. Chi-square tests were used to test for specific differences in proportions.

Logistic regression models were constructed to reexamine these relationships, controlling for potential confounders. Models included a variable designating the presence of a mental condition alone, presence of general medical condition alone, presence of combined mental and physical conditions, age, race, marital status, education, income, and total number of disabling conditions.

The SUDAAN statistical package

(17), with appropriate weighting and nesting variables, was used for all statistical comparisons to account for the sampling weight and the complex stratified survey design

(18).

Results

Sample Characteristics

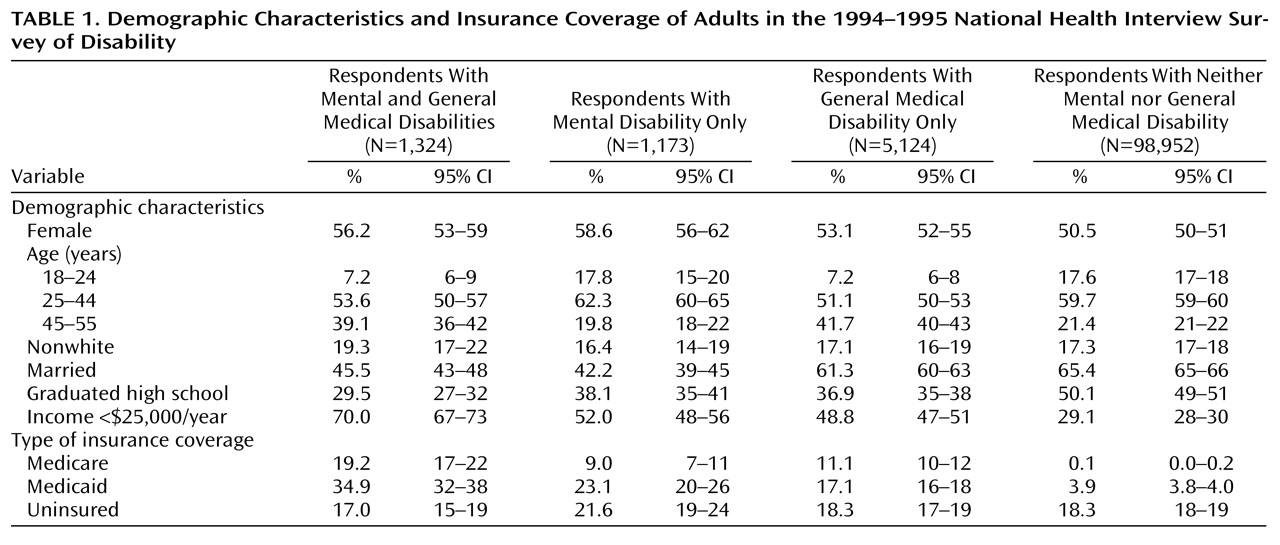

Of 106,573 respondents age 18–55, 7.2% (N=7,621), reported being unable or limited in ability to participate in a major life activity (hereafter referred to as a disability) (

Table 1). A total of 1,173 (1.1%) of the respondents reported a mental disability only, 5,124 (4.8%) noted a general medical disability only, and 1,324 (1.2%) reported combined mental and physical disabilities.

For the United States as a whole, an estimated 9,189,000 individuals age 18–55 had a disabling condition during the study period. A total of 3,026,000, or about one-third of those reporting a disability, identified a mental condition as contributory. This group was fairly evenly distributed between respondents reporting a mental condition alone and those identifying a mental condition in conjunction with a general medical condition.

The most common mental diagnoses were, in descending order of prevalence, 1) anxiety disorders, 2) major depression, 3) bipolar disorder, 4) schizophrenia, and 5) substance use. The rank order was identical for respondents with disabilities attributed to mental conditions alone and those attributed to mental conditions in conjunction with general medical conditions. The most prevalent medical diagnoses in respondents with either combined or general medical conditions were 1) diseases of the musculoskeletal system, 2) respiratory conditions, 3) diseases of the nervous system, 4) endocrine conditions, and 5) hypertension.

Differing conditions were associated with different demographic characteristics. All forms of disability were seen more in women than men, medical disabilities were seen more in older than younger respondents, and mental disabilities were strongly associated with being single or divorced. Comorbid mental and general medical conditions were associated with the lowest levels of education and income.

Functional Correlates of Disability

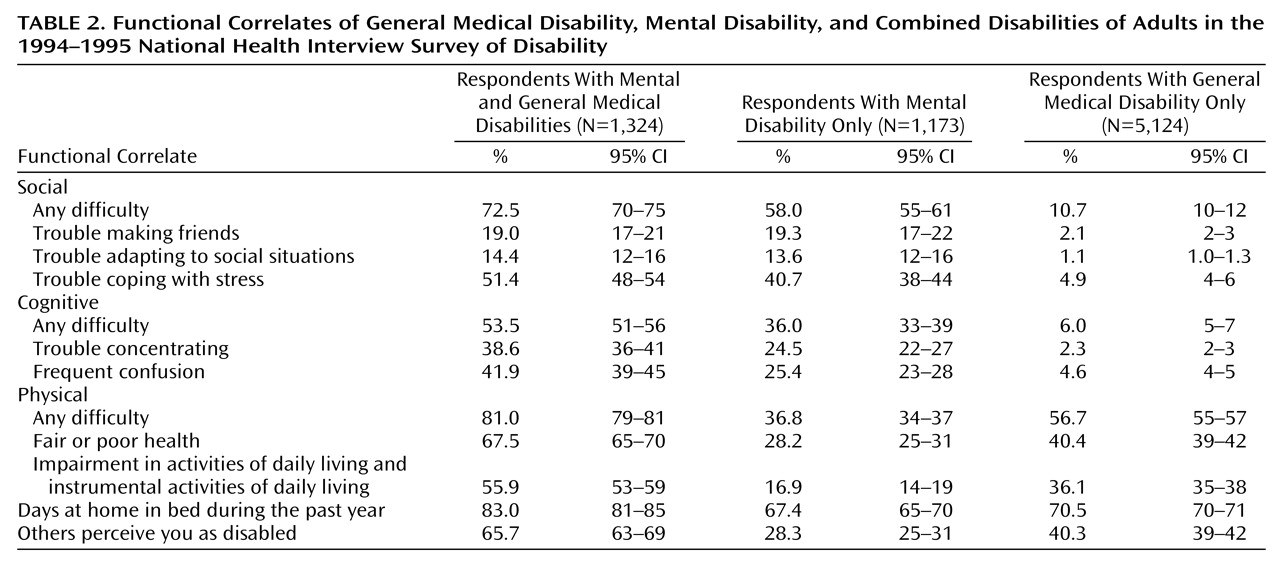

Respondents reporting disability due to a mental condition were more than five times more likely than those with disability due to a general medical condition to report difficulties in social (χ

2=1,322, df=1, p<0.001) and cognitive (χ

2=815, df=1, p<0.001) function (

Table 2). In turn, those with combined mental and physical difficulties were significantly more likely than those with mental conditions alone to report social (χ

2=107, df=1, p<0.001) or cognitive (χ

2=80, df=1, p<0.001) difficulties. Individuals with combined conditions were significantly more likely than those with physical conditions to report physical limitations only (χ

2=247, df=1, p<0.001), bed days (χ

2=73.4, df=1, p<0.001), and that others regarded them as disabled (χ

2=192, df=1, p<0.001). These relationships remained significant in multivariate analyses controlling for age, race, marital status, education, income, and total number of disabling conditions.

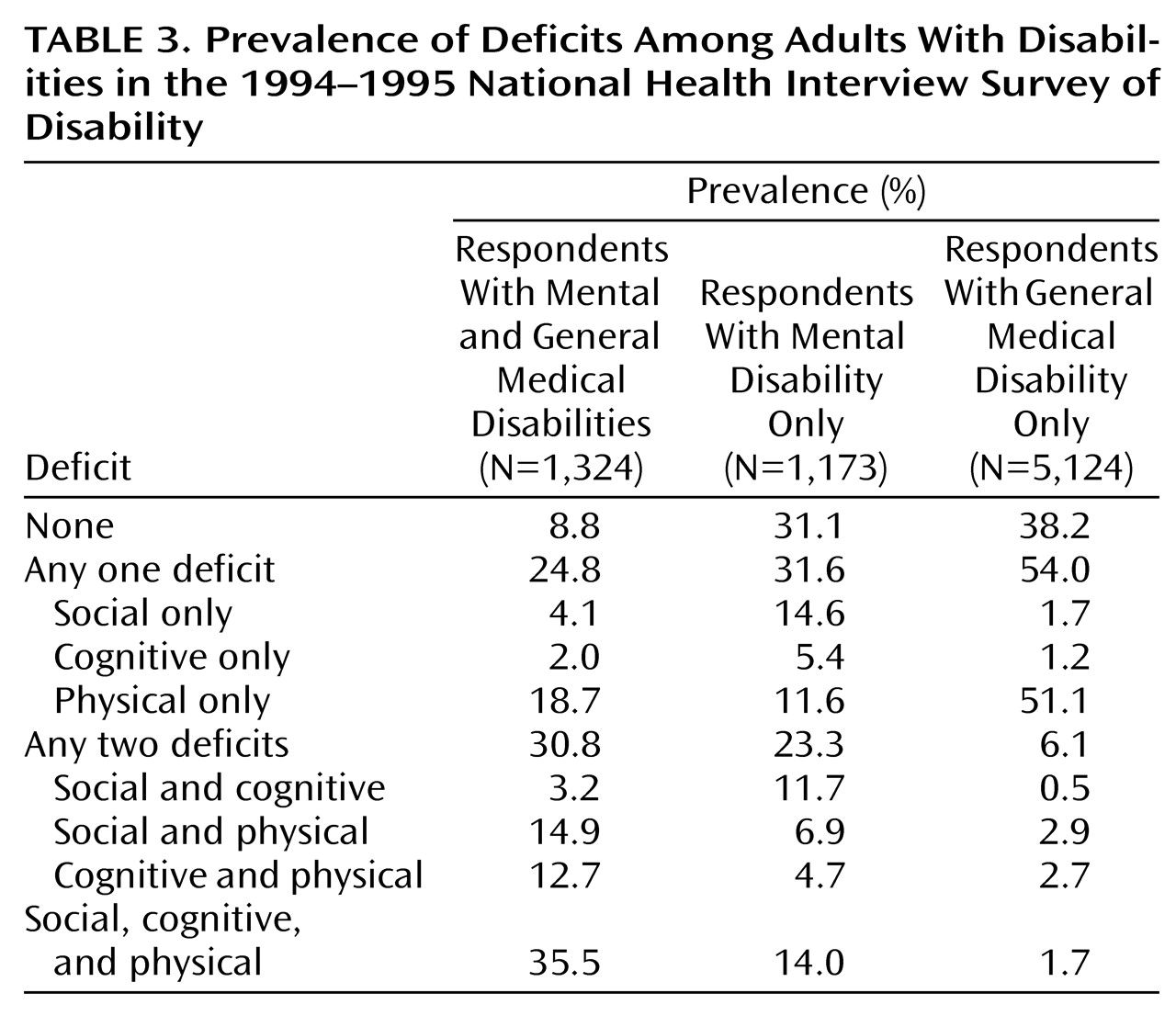

Table 3 demonstrates the prevalence of combined deficits for differing categories of illness. General medical disability was most commonly associated with difficulties in only one domain of function; only 6.1% had some combination of deficits in social, cognitive, and physical function, and only 1.7% had difficulties in all three domains. Mental disability was more commonly associated with combined deficits, with 23.3% identifying deficits in two domains of function and 14.0% reporting difficulties in all three. For those with both mental and general medical disabilities, combined deficits were the rule rather than the exception. A total of 30.8% in this group reported difficulties with two domains, and 35.5% reported difficulties in all three categories.

Work Status and Disability Benefits

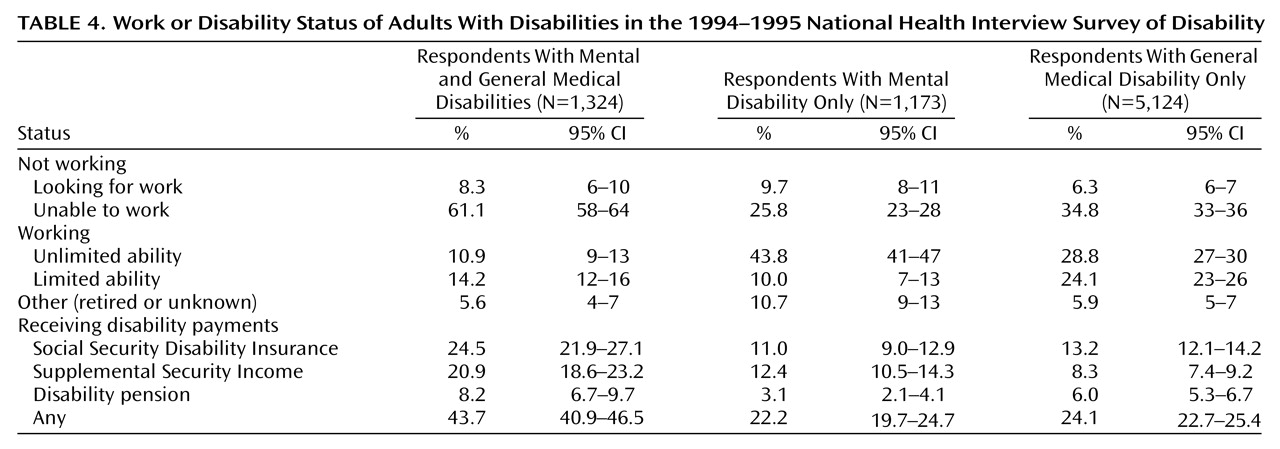

As shown in

Table 4, about one-third of the individuals with a single condition (35.5% of those with mental disabilities and 41.1% of those with general medical disabilities) were not currently working. In contrast, more than two-thirds of those with combined disabilities were unemployed, and fewer than one of nine individuals in this group was working without restrictions. In a logistic regression model, having combined conditions predicted a twofold increase in the likelihood of unemployment compared to having a physical (odds ratio=1.92; Wald χ

2=47.1, df=1, p<0.001) or mental (odds ratio=1.97; Wald χ

2=33.0, df=1, p<0.001) condition.

A total of 43.7% of those with combined conditions, 22.2% of those with mental disabilities alone, and 24.1% of those with general medical conditions were receiving either SSI, SSDI, or employer-based disability payments. In multivariate models, comorbidity conferred a two-thirds increase in odds of receiving disability payments, compared with having only a physical (odds ratio=1.64; χ2=29.7, df=1, p<0.001) or mental (odds ratio=1.66; χ2=33.3, df=1, p<0.001) condition.

Economic, Social, and Job-Based Barriers to Work

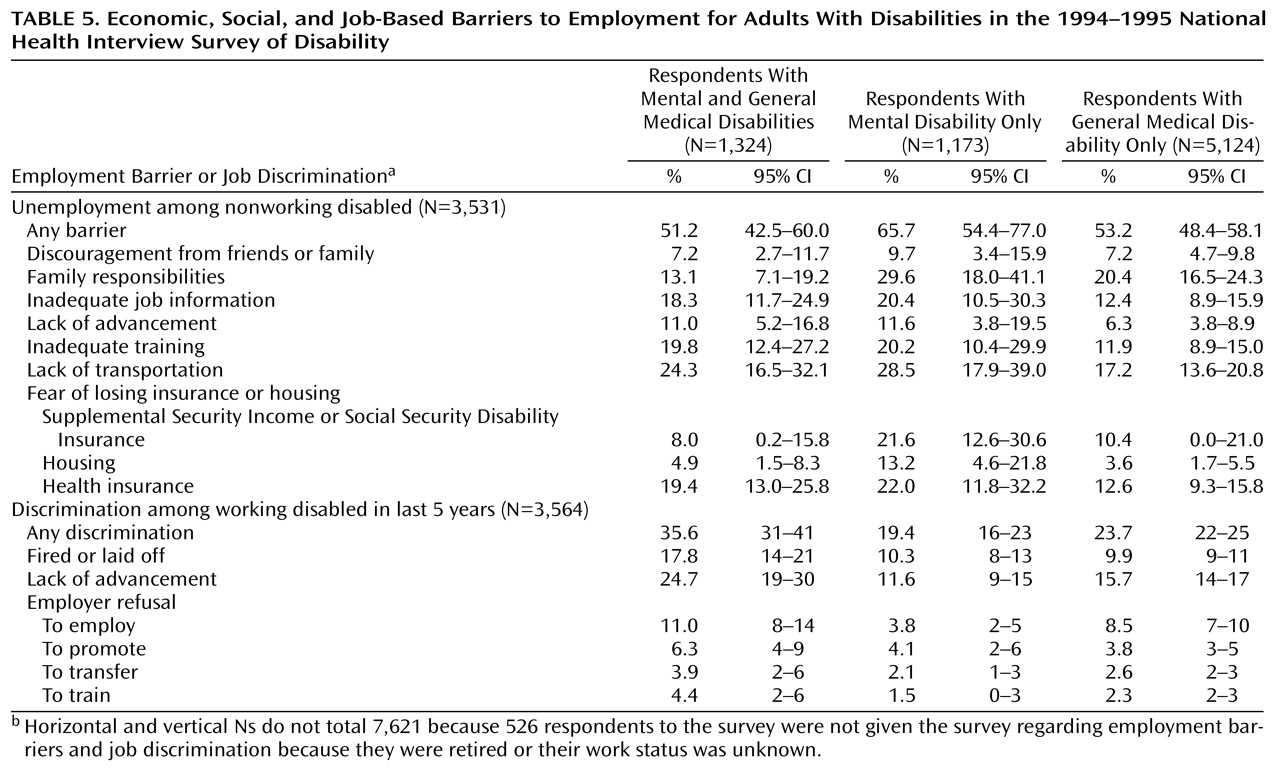

Among the nonworking disabled, 54.1% reported barriers over and above their disabling condition that kept them from finding work (

Table 5). The reasons most commonly cited across groups were family responsibilities (20.0%), lack of transportation to work (19.8%), fear of losing health insurance (14.9%), inadequate job training (14.4%), inadequate job information (14.4%), and fear of losing SSI or SSDI (11.1%). There were no significant differences in either bivariate or multivariate regression models between individuals with mental, physical, or combined disabilities in these barriers to work, although small cell sizes limited the statistical power for conducting these comparisons.

Among individuals who were currently working, 24.2% reported job discrimination on the basis of their disability within the past 5 years. A total of 35.6% of individuals with combined conditions reported some form of discrimination compared with 19.4% for those with mental conditions alone and 23.7% among those with only physical conditions.

Across all three disability groups, the most common forms of discrimination cited were difficulty advancing in work (15.8%), being fired or laid off (10.8%), or being refused employment on the basis of disability (7.9%).