Knowing risk factors for childhood psychopathology would allow us to select children for preventive intervention trials. One risk factor for panic disorder is familial predisposition: the children of parents with panic disorder are at high risk for panic disorder and other anxiety disorders

(1–

4). However, because most of these children will not become ill, family history cannot be used to select children for preventive efforts. One strategy for improving prediction among those already at risk by having a parent with panic disorder is to find additional features that predict a very high risk for anxiety disorders.

One example is “behavioral inhibition to the unfamiliar” (behavioral inhibition), which reflects the consistent tendency to display fear and withdrawal in unfamiliar situations

(5). Behavioral inhibition is stable, detectable early in life, and under some genetic control

(6,

7). Children with behavioral inhibition are shy with strangers and timid in unfamiliar situations.

Behaviors of inhibited school-age children are similar to descriptions of children whose parents had panic disorder and to retrospective descriptions of childhood by adults with panic disorder or agoraphobia

(8–

10). Children with behavioral inhibition also show evidence of greater arousal in the limbic-sympathetic axes

(11), which fits well with hypotheses about the neurophysiological concomitants of anxiety disorders

(12). Moreover, family studies show modest rates of behavioral inhibition among children of parents with panic disorder

(13,

14). These studies suggest that behavioral inhibition indexes a predisposition to development of anxiety disorders.

In our prior work, children with behavioral inhibition had a higher prevalence of multiple (i.e., at least two) anxiety disorders, with overanxious and phobic disorders particularly prominent

(15,

16). Although this work suggested a link between behavioral inhibition and anxiety disorders, its inferences were tentative because of the small study size. We also could not determine whether behavioral inhibition was a specific precursor to anxiety or a more general precursor to other psychopathology

(13,

17,

18).

Because of these uncertainties, we conducted the present study to evaluate three competing hypotheses: 1) behavioral inhibition is a nonspecific index of proneness to development of psychopathology; 2) behavioral inhibition is a nonspecific index of proneness to development of anxiety disorders; and 3) behavioral inhibition is a specific index of proneness to development of specific anxiety disorders.

Method

Three parent groups were recruited

(19): 1) those with panic disorder either with or without comorbid major depression (N=131, 102 of whom had major depression and an additional 11 of whom had spouses with major depression), those with major depression without panic disorder or agoraphobia (N=39), and a comparison group with neither panic disorder nor major depression (N=61). The numbers of children of appropriate age for assessment of behavioral inhibition (i.e., 2–6 years) within the three parent groups were 151, 49, and 84, respectively. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Massachusetts General Hospital. Parents provided written informed consent for themselves and children. Children provided assent.

Parents with panic disorder and major depression were recruited from clinical referrals and advertising. Comparison parents were recruited from hospital personnel and through advertisements. The purpose of the comparison group was to serve as the control group in a “case-control” design for tests of association between child behavioral inhibition and parental panic disorder and major depression, reported earlier

(19); as such it was important that this group not have the main disorders of interest (panic disorder and major depression). We excluded other anxiety disorders associated with behavioral inhibition (such as social phobia) or with anxiety disorders in offspring (agoraphobia and obsessive-compulsive disorder [OCD]). Potential comparison parents were included if they and their spouse did not meet DSM-III-R criteria for panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, OCD, generalized anxiety disorder, major depression, bipolar disorder, or dysthymia. Because we did not want to create a “super-normal” comparison group

(20,

21), we did not exclude individuals with other disorders. For example, we did not exclude comparison parents with posttraumatic stress disorder or simple phobia. However, the rates of these disorders in comparison parents were very low (1% and 5%, respectively) and occurred without comorbid panic disorder or major depression.

Diagnostic Assessments

To grant optimal freedom from bias: 1) only the project coordinator knew the ascertainment group of the parent; 2) staff assessing behavioral inhibition were blind to other data; and 3) psychiatric interviewers were blind to ascertainment status and the behavioral inhibition classification of children.

Both parents were interviewed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R

(22). Social class was assessed with the Hollingshead Four-Factor Index

(23). Psychiatric assessments of children ages 5 and older used the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—Epidemiologic Version (K-SADS-E)

(24), which was completed by the children’s mothers, who also completed the Child Behavior Checklist

(25,

26).

Interviews were conducted by raters supervised by two senior psychiatrists (J.F.R., J.B.). Kappa coefficients of agreement were computed between the interviewers and board-certified psychiatrists who listened to audiotaped interviews. On the basis of 173 interviews, kappas ranged from 0.64 for alcohol abuse to 0.99 for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, with median and mean kappas of 0.86. Good agreement was seen for major diagnoses of interest (panic disorder: kappa=0.96; major depression: kappa=0.86; anxiety disorders: kappa range=0.83–0.96; disruptive behavior disorders: kappa range=0.93–0.99). All subjects were diagnosed on the basis of a consensus judgment by two senior psychiatrists (J.B., J.F.R.). Diagnosticians were blind to ascertainment group, to all nonpsychiatric data, and to all information about other family members.

Assessment of Behavioral Inhibition

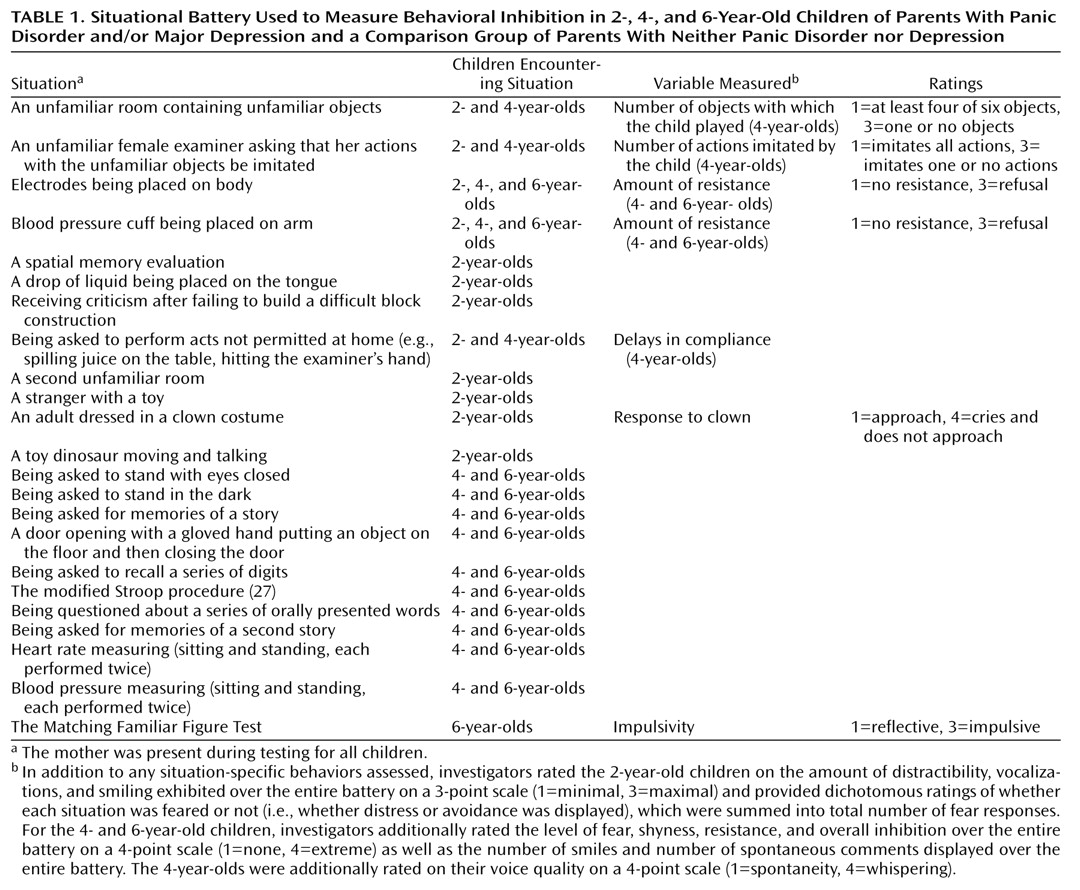

The situational battery used to assess behavioral inhibition is given in

Table 1. Although there is general agreement about the types of behaviors that assess behavioral inhibition, there is little consensus as to how these behaviors should be aggregated into a final index. Therefore, we used three definitions of behavioral inhibition and required that the 2-year-old children meet both of the definitions for which they were eligible while the 4- and 6-year-olds were required to meet at least two of the three.

Dichotomous definition

Two-year-old children categorized as inhibited according to this definition exhibited four or more fears during the situational battery, or their vocalizations or smiling were given a rating of “minimal.” Four- and 6-year-old children were categorized as inhibited if the number of spontaneous comments and smiles was in the lowest 20th percentile of comparison children. High interrater reliability was seen for the coding of smiles (kappa=0.96) and comments (kappa=0.997).

Global definition

Behavioral inhibition according to this definition was based on a 4-point rating of the child’s overall behavior across the entire situational battery made by one of the investigators (J.K.). A rating of 1 reflected extremely uninhibited behavior, and a rating of 4 reflected extremely inhibited behavior (4-point rating reliability: kappa=0.70). Children who received ratings of 3 or 4 were considered inhibited. Only the 4- and 6-year-old children received this rating.

Summary definition

A summary score was derived from a principal factors factor analysis (with varimax rotation) of all the behavioral variables in

Table 1, computed separately for 2-, 4-, and 6-year-old children. We retained factors having eigenvalues greater than one and selected for each age group the factor score that best reflected behavioral inhibition. Children in each age group who had behavioral inhibition summary scores in the upper 20th percentile of children in their age range were classified as inhibited.

Statistical Approach

We first tested associations between predictor and outcome variables and demographic characteristics, considering a characteristic potentially confounding if it was related to both predictor and outcome variables at p<0.10. Then we tested whether behavioral inhibition in the child predicted specific outcomes while controlling for potentially confounding demographic variables

(28). Multiple members of a single family were not independently sampled. To deal with this problem, we used the generalized estimating equation method to estimate general linear models

(29), as implemented in Stata

(30). We used Wald’s chi-square test to assess the statistical significance of individual regressors. When this was not possible because of small cell sizes, we used Fisher’s exact test for two-way tables or exact logistic regression or more complex models

(31).

To determine whether the association of behavioral inhibition with outcomes could be accounted for by parental diagnosis, we used the generalized estimating equation method to predict the outcome by using behavioral inhibition with parental diagnosis covaried. If behavioral inhibition predicted outcome in such an equation, its association could not be accounted for by parental diagnosis. We also examined the interaction between behavioral inhibition and parental diagnosis in predicting outcome. All analyses were two-tailed and used the 5% significance level.

Results

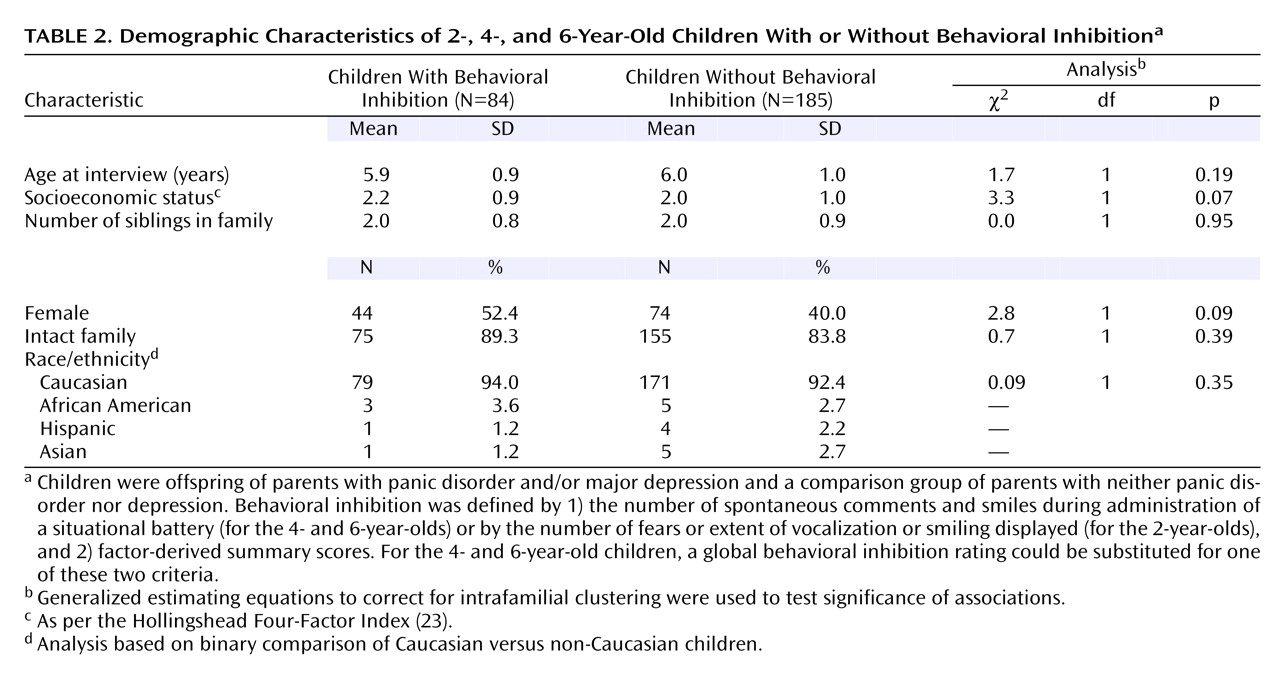

Of the 284 children who underwent the situational battery for assessment of behavioral inhibition, 216 were assessed with the K-SADS-E and 239 were assessed with the Child Behavior Checklist. Because of overlap in children assessed with each of these measures, a total of 269 children were included in the analyses. No demographic differences were detected between inhibited and noninhibited children (

Table 2). The group of inhibited children had more subjects who were female and of a lower social class. Even though the differences did not reach statistical significance, whenever these variables were related to the outcome variable, they were covaried.

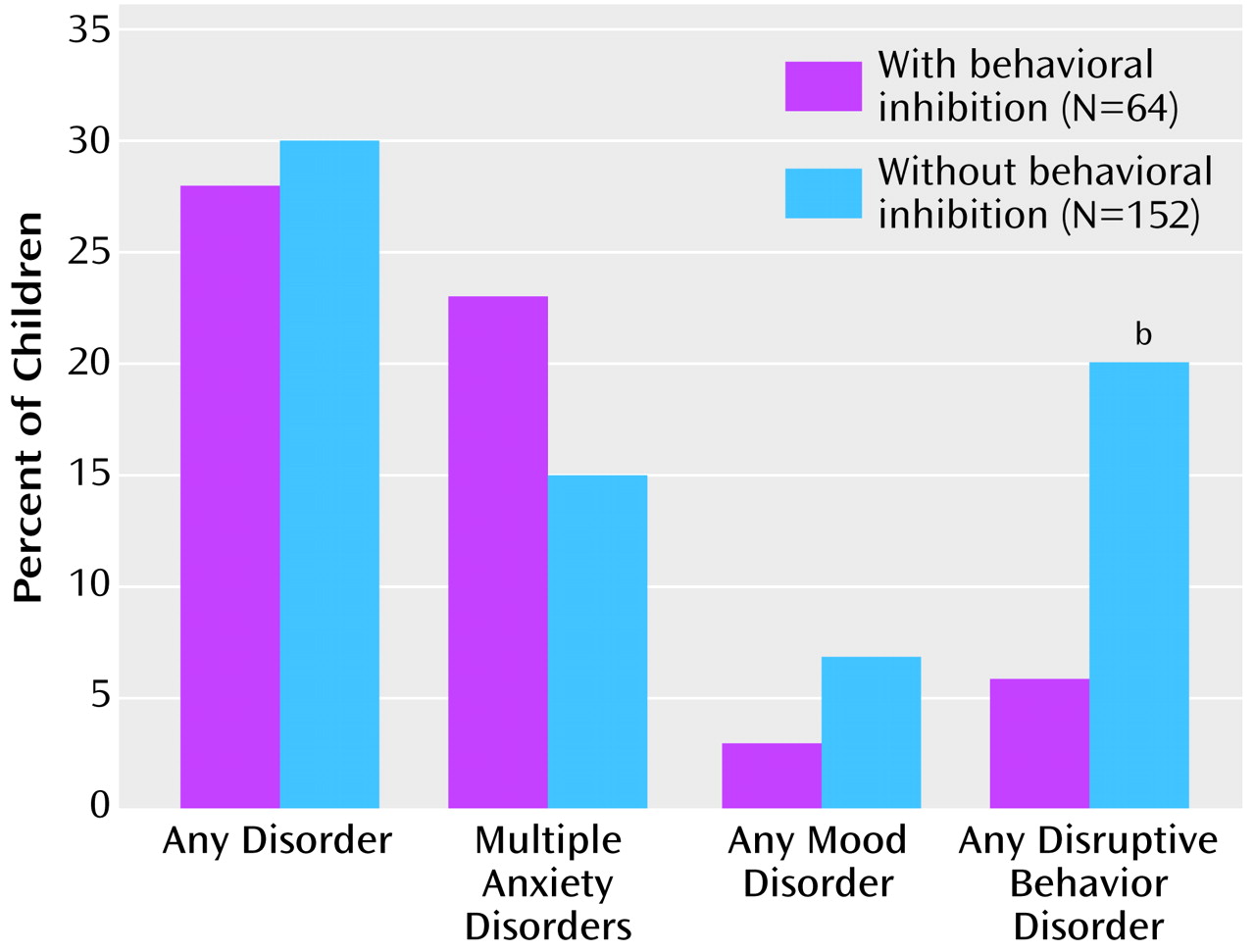

We found no differences between inhibited and noninhibited children in the rate of any disorder or any mood disorder (

Figure 1). The rate of any disruptive behavior disorder was significantly higher in noninhibited children than in those with behavioral inhibition (20% versus 6%, respectively) (odds ratio=0.30, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.11–0.82).

The association between behavioral inhibition and any disruptive behavior disorder was independent of parental diagnosis (odds ratio=0.22, 95% CI=0.06–0.71; p=0.006, Fisher’s exact test), and there was no significant interaction between parental diagnosis and behavioral inhibition.

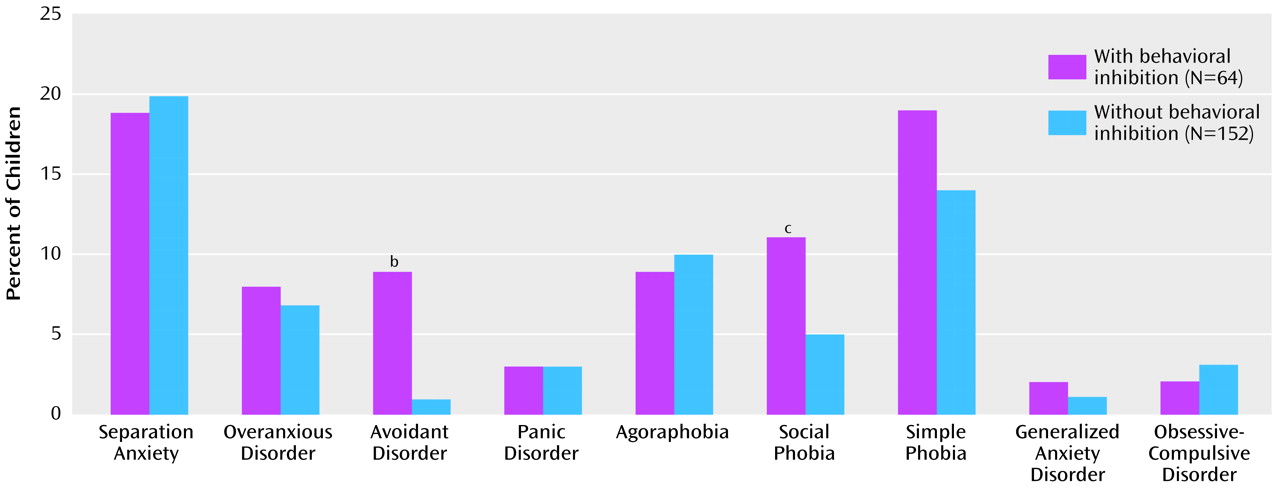

For specific anxiety disorders (

Figure 2), comparisons between inhibited and noninhibited children revealed significant differences only in the rate of avoidant disorder (9% versus 1%, respectively) (odds ratio=7.8, 95% CI=1.5–39.6).

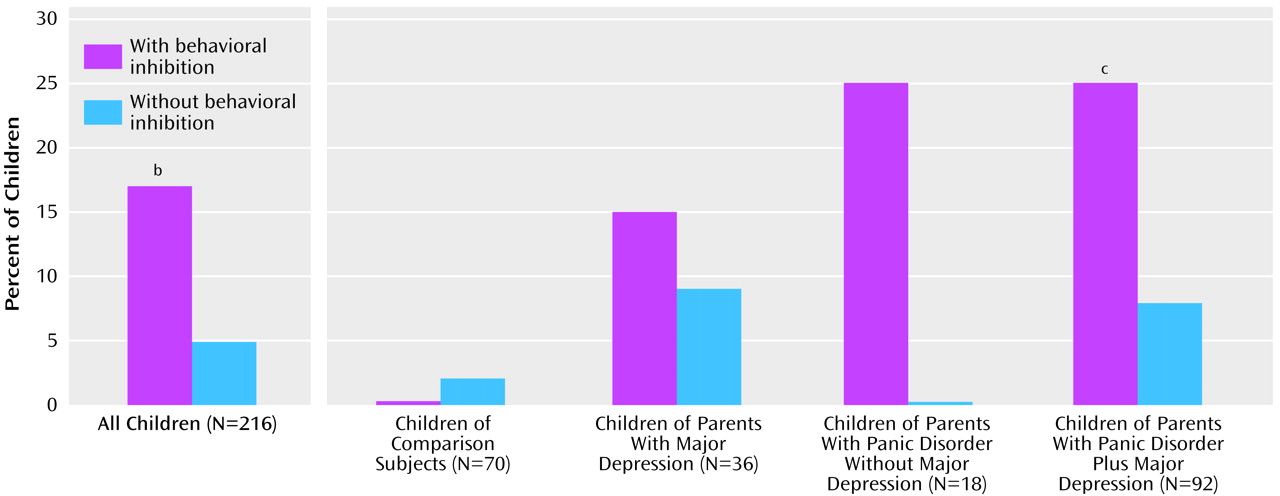

Because of the similarities between social phobia and avoidant disorder, we combined the two into one category: social anxiety disorder. As seen in

Figure 3, the rate of social anxiety disorder was significantly higher in inhibited children than in children without behavioral inhibition (17% versus 5%, respectively) (odds ratio=3.7, 95% CI=1.4–9.9). The main effect of behavioral inhibition on social anxiety disorder was independent of the main effect of parental diagnosis (Wald χ

2=10.15, df=4, p=0.04; per generalized estimating equation method: odds ratio=3.2, 95% CI=1.2–8.5; z=2.28, p=0.02). There was no significant interaction between parental diagnosis and behavioral inhibition in predicting social anxiety disorder (p=0.87, exact test). Nonetheless, a significantly higher rate of social anxiety disorder among inhibited children compared to noninhibited children was found only among offspring of parents with panic disorder either with major depression (25% versus 8%, respectively; odds ratio=3.6, 95% CI=1.1–12.1) or without (25% versus 0%, n.s.). In contrast, no differences were observed in comparison families (0% versus 2%).

On the attention problems scale of the Child Behavior Checklist, significantly higher scores were seen in the noninhibited children (mean=52.1, SE=0.5) than in inhibited children (mean=50.8, SE=0.3) when socioeconomic status was covaried (odds ratio=0.89, 95% CI=0.79–0.99 [Wald χ2=5.7, df=2, z=–2.17, p=0.03]).

Results were consistent regardless of behavioral inhibition definition. The rate of any disruptive behavior disorder was significantly higher in noninhibited children than in inhibited children across all three behavioral inhibition definitions (dichotomous: odds ratio=0.18, 95% CI=0.04–0.80 [Wald χ2=5.1, df=1, p=0.02]; global: odds ratio=0.34, 95% CI=0.14–0.84 [Wald χ2=5.4, df=1, p=0.02]; summary: odds ratio=0.32, 95% CI=0.12–0.83 [Wald χ2=5.4, df=1, p=0.02]). Similarly, the significantly higher rates of avoidant disorder and social anxiety disorder reported in the children with behavioral inhibition remained significant per the global definition (avoidant: odds ratio=5.4, 95% CI=1.1–27.7 [Wald χ2=4.1, df=1, p=0.04]; social anxiety disorder: odds ratio=3.3, 95% CI=1.2–8.8 [Wald χ2=5.51, df=1, p=0.02]) and the summary definition (avoidant: odds ratio=4.4, 95% CI=1.0–19.2 [Wald χ2=3.82, df=1, p=0.05]; social anxiety disorder: odds ratio=3.04, 95% CI=1.15–8.01 [Wald χ2=5.07, df=1, p=0.02]) of behavioral inhibition.

Discussion

Behavioral inhibition in children was selectively associated with a higher risk for avoidant disorder and social phobia and a lower risk for disruptive behavior disorders. No association was detected between behavioral inhibition and other disorders, which suggests that behavioral inhibition may have specific associations with social anxiety in children.

Our prior work also found significant associations between behavioral inhibition and overanxious, avoidant, and phobic disorders

(15,

16). Moreover, at a 3-year follow-up (ages 8–11), these children had significantly higher rates of multiple anxiety disorders, avoidant disorder, separation anxiety disorder, and agoraphobia

(16).

Our findings linking behavioral inhibition with social anxiety support a body of literature documenting similar results. Parents of inhibited children have histories of overanxious and avoidant disorders in childhood

(32), and prospective studies have supported the link between behavioral inhibition and social phobia in children. In one, youngsters classified as inhibited at 21 or 31 months had significantly higher rates of current general social anxiety at age 13 than uninhibited youngsters

(33). No other types of anxiety differed between groups.

Hayward and colleagues

(34) assessed behavioral inhibition (using retrospective self-reports) in a sample of over 2,000 ninth-graders subsequently interviewed for depression and social phobia at yearly intervals throughout high school. Subjects who showed evidence of behavioral inhibition had a greater than fivefold risk of developing social phobia than other subjects. Retrospective studies of adults with social anxiety or social phobia have reported links between social anxiety disorders and childhood behavioral inhibition. Mick and Telch

(35) found that college undergraduates with social anxiety scored significantly higher on behavioral inhibition than those with generalized anxiety disorder or comparison subjects.

In our study, behavioral inhibition was associated with social anxiety mainly among children whose parents had panic disorder either with or without depression. This is consistent with the idea that the familial factors that cause behavioral inhibition could overlap with those that cause panic disorder and possibly depression. It also suggests that behavioral inhibition predicts children’s social anxiety beyond what can be predicted by the parental disorders. Thus, our results suggest that parental panic disorder and child behavioral inhibition could be used to identify children at high risk for social anxiety who may benefit from preventive and early intervention strategies.

The finding that behavioral inhibition was less common among children with disruptive behavior disorders confirms findings by other groups of an inverse association between behavioral inhibition or anxiety and disruptive behavior. For example, Walker et al.

(36) reported that the presence of comorbid anxiety disorders in boys with conduct disorder was inversely associated with predatory activity and aggression. Similarly, Kerr et al.

(37) reported that behavioral inhibition protected both disruptive and nondisruptive boys against delinquency.

Our findings should be viewed in light of some methodological limitations. Because we relied on cross-sectional data, we cannot be certain that behavioral inhibition preceded the onset of social anxiety disorder in the children affected with this disorder. The assessment of psychopathology in the children used interviews with mothers. Parents with psychiatric disorders may have exaggerated symptoms in their children, whereas mothers without psychopathology may have underreported problem behaviors

(38,

39). The lack of direct psychiatric interviews with children may have decreased the sensitivity of some diagnoses, especially for “internalizing” disorders. However, we found high rates of these disorders in our study. Also, the children in our study had a mean age of 6 at the time of diagnostic assessment. Young children have limited expressive and receptive language abilities; they cannot easily sequence events in time and have difficulties with abstraction. Thus, there is a real question about whether their self-perceptions, memories, feelings, and reported behavior can be reliably assessed through self-report, especially with regard to lifetime history of psychopathology

(40). Although limited, studies of interview techniques for young children suggest that their responses are unreliable

(41).

Also since our proband parents were clinically referred, the generalizability of our findings is limited to referred study groups. Although we made a distinction between parents with panic disorder and major depression and those with panic disorder only, because of the variable age at onset it is possible that some of the parents with only panic disorder will eventually develop major depression. Finally, we must be cautious when making inferences about disorders that showed no association with behavioral inhibition because our study group is still young; further follow-up is needed to assess emergent disorders.

Despite these considerations, in a comprehensive examination of psychiatric correlates of the laboratory-based temperamental trait termed “behavioral inhibition” in a large group of children, we found that behavioral inhibition was selectively associated with a greater risk for avoidant disorder and social phobia in children, which suggests that behavioral inhibition may have specific associations with social anxiety in young children. Considering that behavioral inhibition can be identified earlier in life than manifest anxiety, repeated confirmation of these findings could have important implications for the prevention of anxiety disorders in children.