Because conscious awareness of one’s knowledge allows behavior to be based on reflection rather than to occur as a direct response to a stimulus, impaired conscious awareness might be a critical determinant of behavior abnormalities in schizophrenia

(1–

3). However, the functional mechanisms underlying the relationship between a particular subjective experience and abnormal behavior are unknown. Koriat and Goldsmith

(4) put forward a framework that allows investigation of these mechanisms. They posited that monitoring and control, two processes related to executive functions, play a crucial role in situations where behavior is determined by one’s knowledge. A real-life, prototypical situation is that of people who recount past events and decide what information to report. They first monitor the accuracy of recovered information. The monitoring process is expressed subjectively as a feeling of confidence that the information is correct or not. Then, subjects decide whether to volunteer or to withhold the information. The decision is based on a control process that depends on the feeling of confidence associated with the information and on the criterion for volunteering the information. The latter depends on situational demands such as motivation and incentives. The information is volunteered only if the associated confidence judgment exceeds the criterion.

These processes can be assessed experimentally (4). Subjects first take a general knowledge test under forced-report instructions. They are required to answer all the questions on the test and to assess their subjective experience by providing confidence judgments regarding the correctness of each answer. Then, they repeat the task under free-report instructions and either with or without a monetary incentive for providing accurate answers. This procedure makes it possible to measure monitoring effectiveness (i.e., the extent to which confidence judgments adequately assess the correctness of responses) and control sensitivity (i.e., the extent to which the volunteering or withholding of responses is sensitive to confidence judgments). The effects of incentives on the subjects’ control sensitivity are assessed by comparing response criteria in the no-incentive condition with that in the incentive condition.

According to this framework, behavior abnormalities of patients with schizophrenia might be related to impaired monitoring of the correctness of their knowledge. Moreover, in patients with schizophrenia, subjective experience might be less strictly adhered to in controlling behavior and/or control sensitivity might be less influenced by incentives. We used Koriat and Goldsmith’s method to investigate these hypotheses.

Method

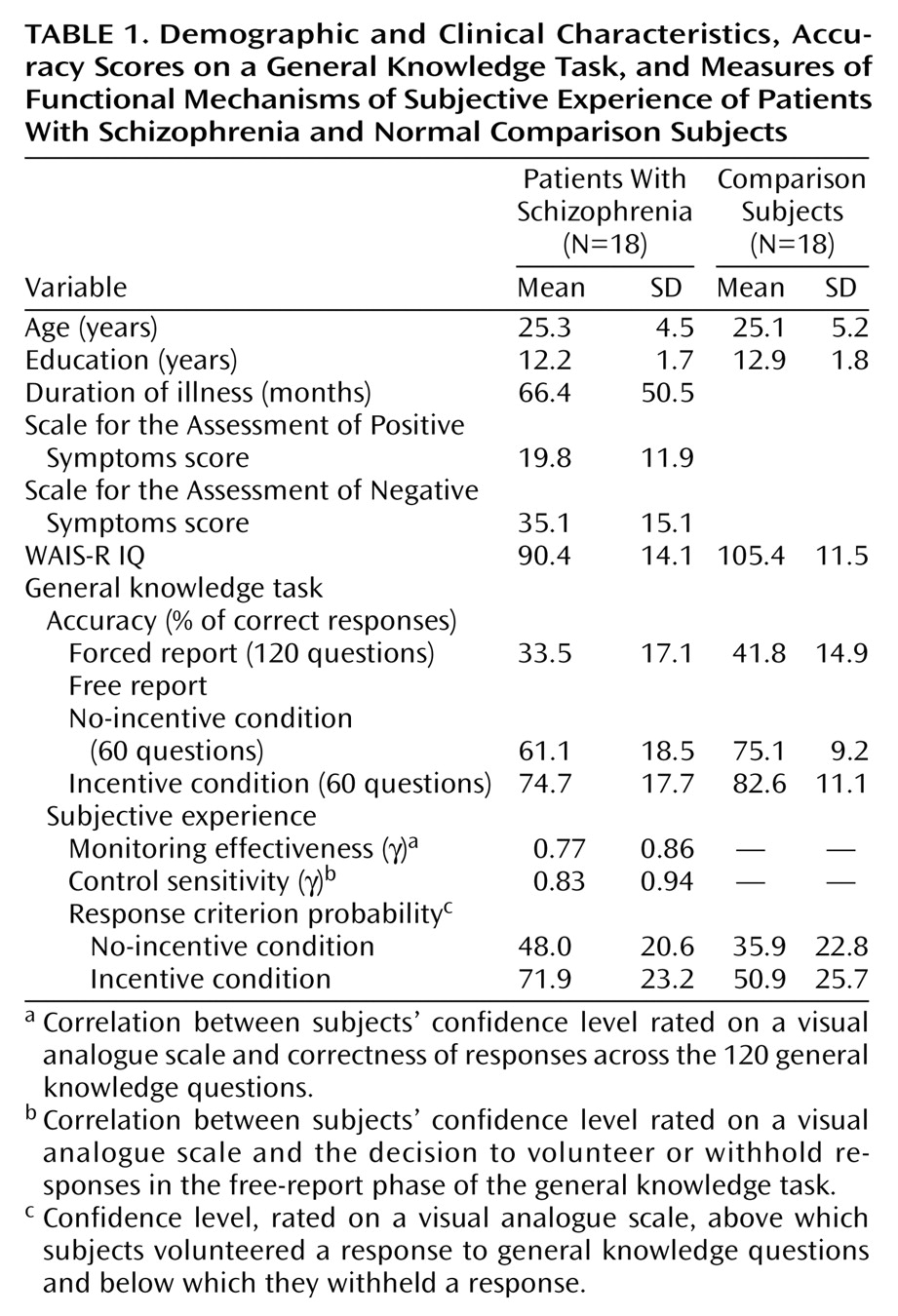

Eighteen outpatients (eight women and 10 men) participated in the study (

Table 1). They fulfilled DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia (paranoid: N=5; residual: N=7; disorganized: N=3; undifferentiated: N=3). Eight patients were receiving typical neuroleptics, and 10 were receiving atypical neuroleptics. All medication was administered in a standard dose.

The comparison group consisted of 18 normal subjects (eight women and 10 men). The two groups did not differ significantly in age or education. IQ, assessed with the WAIS-R, was significantly lower in patients than in comparison subjects (t=–3.51, df=34, p<0.01).

All subjects provided informed and written consent. They were paid 200 French francs for their participation.

A general knowledge task was used. It consisted of 120 questions of varying difficulty requiring a single word answer. Examples of the questions are: “What color are emeralds?” (green), and “What does the name of the Russian newspaper Pravda mean?” (truth). The experiment was conducted in two phases.

In phase 1, subjects took a version of the test under forced-report instructions. All 120 questions were presented one by one, and, after reading each question aloud, the subjects had to give an answer, even if they had to guess, and to rate their confidence that the answer given was correct by using a visual analogue scale.

In phase 2, the same test was presented under free-report instructions. The subjects were told that they could choose whether or not to answer a given question. Accurate responding was induced by one of two conditions. In the no-incentive condition, tested with the first 60 questions, no monetary incentive was offered for performance. The subjects merely had to decide whether to volunteer or withhold the answer to any given question. In the incentive condition, tested with the 60 remaining questions, the subjects were informed that, in addition to the basic payment for their participation, they would be paid 5 French francs for each correct answer and lose the same amount for each incorrect answer.

Monitoring effectiveness was evaluated with Goodman-Kruskal γ correlations between subjects’ confidence judgments and the correctness of the response calculated across the 120 items. Control sensitivity was evaluated by γ correlations between subjects’ confidence judgments and the decision to volunteer or withhold responses in the free-report phase. Response criterion probability, i.e., the confidence level above which the subject volunteered the candidate answer and below which he or she withheld it, was estimated by using a computational procedure (4).

Variables were subjected to analysis of variance with groups as a between-subject factor and test conditions (forced report versus free report in the no-incentive condition, and the no-incentive condition versus the incentive condition) as a within-subject factor.

Results

Accuracy scores, i.e., the proportions of correct responses among the responses that were volunteered, were higher under the free-report than under the forced-report condition (F=192.46, df=1, 34, p<0.001) and higher under the incentive condition than under the no-incentive condition (F=32.81, df=1, 34, p<0.001). Accuracy scores were higher in the normal subjects than in the patients (F=5.78, df=1, 34, p=0.02). The patients’ accuracy improved to the same extent as that of normal subjects in the free-report and incentive conditions, as indicated by the absence of any interaction between group and condition (F<2.77, df=1, 34, p>0.10).

Confidence levels for incorrect responses, but not for correct responses, were higher for the patients than for the normal subjects (t=2.71, df=34, p=0.01). The level of monitoring effectiveness was lower in the patients than in the normal subjects (F=6.41, df=1, 34, p<0.02). Therefore, the patients were less successful in subjectively assessing the correctness of their responses.

The patients exhibited an impaired control sensitivity, compared with the normal subjects (F=5.52, df=1, 34, p<0.03). The patients did not follow closely their confidence judgments in deciding which answers to volunteer. Response criterion probability values were significantly higher under the incentive condition than under the no-incentive condition (F=14.47, df=1, 34, p=0.001), and significantly higher in the patients than in the normal subjects (F=8.14, df=1, 34, p=0.007). Thus, the patients adopted a more conservative response criterion than the normal subjects. However, the effect of incentives on response criterion probability was similar in the patients and the normal subjects (F=0.77, df=1, 34, p=0.39).

Secondary statistical analyses carried out on data for a subgroup of 12 patients whose IQ (mean=97.2, SD=12.4) was not significantly different from that of a subgroup of 12 normal subjects (mean=99.7, SD=9.2) (F=0.31, df=1, 22, p=0.58) yielded similar conclusions. Therefore, patients’ impairments were not related to low intellectual capacities.

Discussion

Schizophrenia impairs the relationship between subjective experience and behavior for two reasons. First, the monitoring process is defective. Compared to the normal subjects, the patients were less successful in subjectively assessing the correctness of their responses, probably because their subjective confidence in incorrect responses was increased. Second, schizophrenia impairs control sensitivity. Despite the fact that the patients adopted a conservative control policy, their confidence judgments were less strictly adhered to in deciding which responses to volunteer. Therefore, the patients’ behavior was less determined by subjective experience than that of the normal subjects, a finding reminiscent of Bleuler’s proposal that schizophrenia is characterized by a splitting of thought and action. This finding might be explained by poor stability of subjective experience and/or by the increasing role that unconscious processes play when subjective experience is defective. Whether this impaired relationship may be observed in other patient groups with executive dysfunctions, such as those with frontal lesions, has yet to be established.

Whereas the patients’ control was defective, its modulation by incentives was still intact. This finding confirms that patients with schizophrenia improve their performance in tasks assessing executive functions when they are given monetary incentives

(5). This finding may have implications for cognitive remediation, because any strategy that enhances patients’ motivation should improve their adaptation to real-life situations.