It has been suggested that, because they do not have older siblings, only children in the family acquire more autocratic, less interactive interpersonal styles and that this has negative consequences for peer popularity (1). However, previous studies of these psychosocial developmental risks among only children are incompatible. Many involved sporadic observations, qualitative notions, or small/biased data samples. In addition, previous studies lacked data on parents’ characteristics and their relationships with their children, which should be examined and considered (2). In a more recent study (3), peer rejection during childhood was found to be the strongest independent predictor of adolescent antisocial behavior among male subjects. We hypothesized that growing up as an only child and probably being at risk for peer rejection may lead to a greater risk for antisocial problems, i.e., criminality in adulthood. To our knowledge, epidemiological examination of an association between being an only child and committing a registered crime based on a large database has never been performed. We used a prospectively collected, genetically homogenous birth cohort database and took into account perinatal, maternal, and paternal risk factors.

Method

The Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort is an unselected, general population birth cohort that includes 96% (N=12,068) of all births in 1966 that occurred in the provinces of Lapland and Oulu. The data collection has been described in detail elsewhere (4). The present study included 5,587 male subjects who were alive and living in Finland at the age of 16 and who did not decline the use of data obtained during the 31-year follow-up. Female subjects were excluded because there was a small number of female criminals in the cohort.

Data on registered crimes of the male subjects were collected from computerized files maintained by the Ministry of Justice for subjects between 15 and 32 years of age. This national register includes records of all crimes that have come to the attention of the criminal justice system in Finland. The category of violent crimes included homicide, assault, robbery, arson, sexual crime, and violation of domestic peace. All other crimes were defined as nonviolent. The prevalence of criminal offending among the 5,587 men at the age of 32 was 3.8% (N=211) for violent crimes and 7.1% (N=397) for nonviolent crimes.

Being an only child was defined at the age of 14 through questionnaire (i.e., “Number of children in the family now and earlier?”). Of the confounding variables, the perinatal risk factors included low birth weight (<2500 g), preterm birth (<37 weeks), perinatal brain damage (5), and maternal smoking during pregnancy (e.g., smoked daily during the entire duration of pregnancy versus stopped before pregnancy/never smoked). Maternal risk factors included low maternal age (20 years or younger) and a negative attitude toward the pregnancy (did not want the pregnancy/mistimed the pregnancy versus wanted the pregnancy). A paternal risk factor was the father’s absence during childhood until the age of 14.

To explore the effect of being the only child in the family in combination with other risk factors (i.e., perinatal/parental) on committing a crime, odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were calculated for violent and nonviolent offenses committed by the male cohort members characterized by several combinations of risk factors. The missing data in each group reached a maximum of 6.2% of the total male cohort. The only-child versus not-only-child groups did not differ in relation to the mother’s social class at birth (88.6% [N=202] and 77.3% [N=3,852] in each group, respectively, were in social class I–III and farmers) or proportions of the probands with mental disorders (5.1% [N=13] versus 4.6% [N=229]).

Results

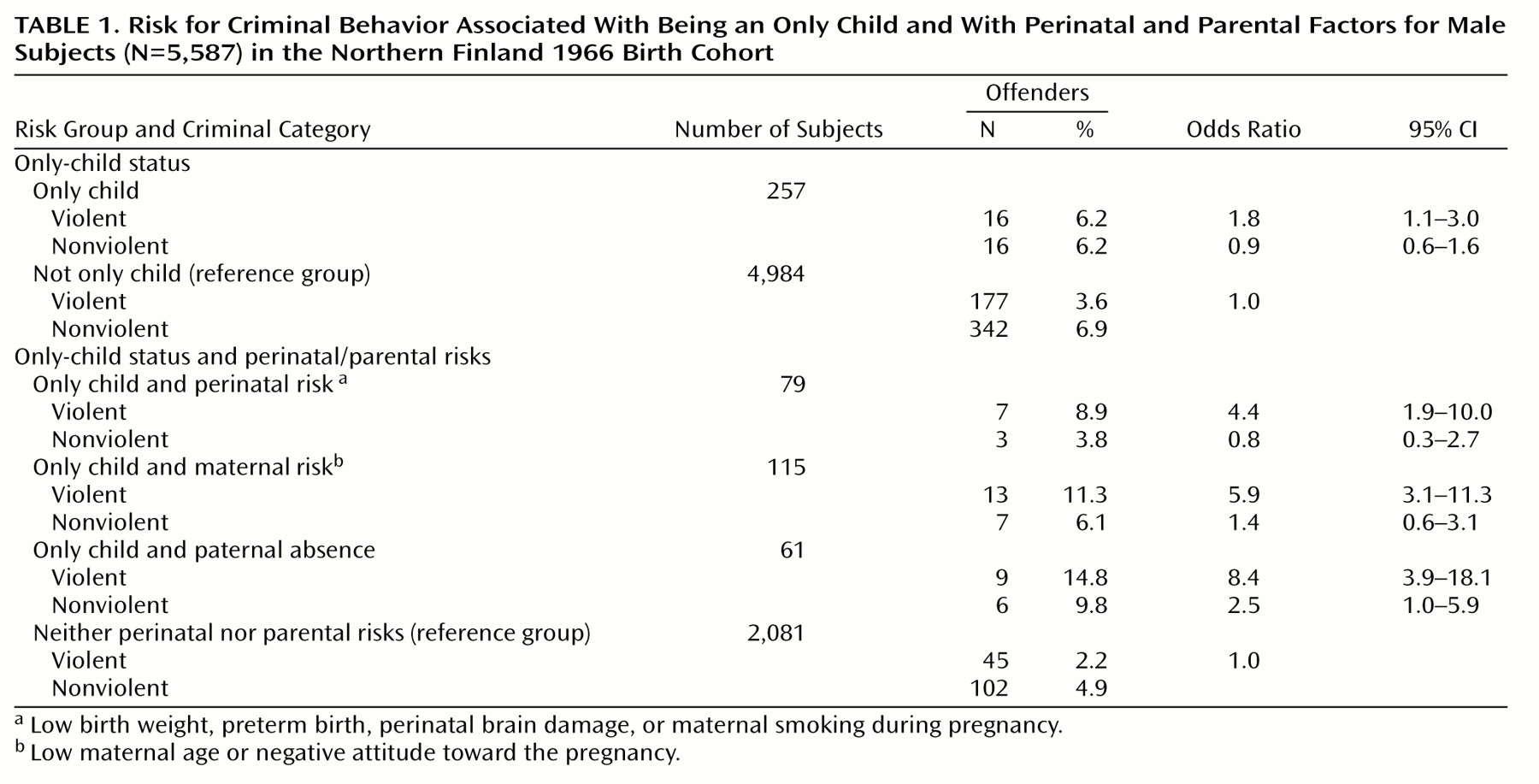

Among male subjects with complete data, 257 were only children and 4,984 were not only children (

Table 1). Sixteen (6.2%) of those who were the only child in the family committed a violent crime, compared with 177 (3.6%) of those who were not only children. Thus, being an only child increased the crude odds ratio for committing a violent crime later in life relative to not being an only child up to 1.8-fold. No association between being an only child and committing a nonviolent crime was noted.

Table 1 presents the results of the analyses with multiple risk factors. Being an only child combined with a perinatal risk increased the odds ratios for committing a violent crime up to 4.4-fold. If maternal or paternal risks were present, the odds ratios for violent offenses were higher, reaching 5.9-fold and 8.4-fold levels, respectively. However, only children were not at risk for committing nonviolent offenses, except in cases were the father was absent (odds ratio=2.5).

Discussion

Our main finding is that male subjects who were raised without siblings had higher rates of arrests for violent offenses later in adulthood. When perinatal or parental risk factors were combined with being an only child, the odds ratios increased fourfold to eightfold. Interestingly, paternal absence was the strongest risk factor when combined with growing up without siblings; the risk of committing a violent crime was twice as high as the risk when being an only child was combined with perinatal risk factors. Our findings are consistent with those of Virkkunen et al. (6). A novel finding, however, is that paternal absence among only children resulted in an eightfold greater risk for committing a violent crime but a much smaller risk for committing a nonviolent crime. Further studies are required to see whether the finding is correlated with paternal genetic factors or environmental risks.

We think that more fathers suffering from antisocial personality disorders are perhaps absent from home and, therefore, that genetic associations could, in part, explain our findings. Lahey et al. (7), however, predicted that genetic influences would exert only indirect effects on the antisocial behavior of a child.

In our study, maternal risks combined with being the only child significantly predicted committing a violent crime but not a nonviolent crime. In our opinion, this effect may be linked to the fact that a solo mother’s capacity to contribute to the development of her child’s sense of justice is impaired. Furthermore, the only children in the family may miss the positive effect of siblings in social learning. It has been suggested that parents of aggressive children show them little warmth and affection (8, 9). A new finding in our study is that the mother’s negative attitude toward the pregnancy and/or her young age when the child was born increased the risk for violent offenses in adulthood among the only children.

Some perinatal biological risks have been found to be linked with adult violent behavior (10, 11). Our study not only confirms these findings but also highlights the effect of psychological risks during the perinatal period in predicting commission of violent but not nonviolent offenses later in life. A secure, loving, and supportive family environment is known to be highly effective in teaching children social skills (12). We conclude that solo mothers of only children need special somatic and psychosocial support in maternity clinics so that violent behavior in childhood as well as adulthood can be prevented or at least minimized.