Threat to the Principle of Fidelity

First we need to recall a core feature of the relationship between psychiatrist and patient, the framework of trust. This enables people to consign their well-being to professionals who, in turn, serve pivotally in the provision of health care, including working “for the benefit of the sick”

(6, p. 6). This principle of fidelity is reflected in diverse ethical theories, including promoting patients’ interests in order to maximize the common good, respecting patients’ autonomy as a paramount principle, and encouraging professionals to strive toward virtuous actions

(7, pp. 62–69).

The current “corporatization” of health seriously undermines the principle of fidelity

(8). Policies intrinsically promoting the interests of clinical populations potentially prevent clinicians from serving individual patients and thereby escalate the risk for moral harm. Efforts to control costs result in systems sensitive to economic priorities but “uninformed” about clinical judgment

(5, p. 24). For example, curtailed inpatient treatment may allow resources to be distributed among the many but also greatly diminish the well-being of a minority of people suffering from severe forms of mental illness.

Another interference with the principle of fidelity is juxtaposing psychiatrists’ financial interests alongside patients’ needs. In certain health care systems, for example, income varies according to treatment provided, raising the hazard that decisions will be motivated by economic rather than clinical factors. Psychiatrists may thus withhold certain treatments, information about those treatments, or financial facts that affect proper clinical judgment

(5, p. 21). Moreover, recognition by patients of their psychiatrists’ conflicts over costs may erode the trust intrinsic to an effective relationship. This situation already prevails in that the public is aware of health care systems’ inducement of clinicians to limit treatment (e.g., offering incentives to order fewer special tests)

(9,

10). At the same time, clinicians have argued that this intrusion prevents them from working for a particular patient when pressed into weighing relative interests of patients and from obtaining fully informed consent because of “gag rules.”

Problems With the Drive for Efficiency

Efficiency, ostensibly the justification for policies of contemporary health care systems, is grounded in the theory that the right action, judged impersonally, gives equal weight to every person’s interests (see reference

11). In its most familiar version, the argument runs that the best state of affairs entails the greatest amount of human satisfaction and, therefore, efficient care should receive priority over inefficient care. Efficiency proponents contend that decision making governed by cost-effectiveness not only reaps economic benefit but also avoids arbitrary practices (such as discriminating against the aged), thereby promoting the confluence of efficiency and fairness. (Eddy illustrated the clinical application of this approach across a population of patients [

12–

14].)

On the other hand, critics of the efficiency argument note that it can impose harm on particular groups by denying them a rightful claim to resources. Harris

(15,

16), for example, posited that policy driven by efficiency suffers from a bias favoring treatments and illnesses that require the fewest resources (“economism”). Criticism of managed mental health care reflecting this view highlights the use of cheaper treatments (e.g., medication when psychotherapy is indicated), less intensive care

(17), insufficiently trained “gatekeepers”

(18,

19) who apply guidelines based on spurious data

(20), choice of treatment quality based solely on duration and cost

(21), arbitrary limits on the period of treatment

(22,

23), and efficiencies that may curb treatment efficacy

(24). These practices suggest that while efficiency-dominated policy may profess impartiality, in fact it imposes discrimination against patients with certain conditions or requiring particular treatments

(15,

16).

How Maximizing the Common Good Fails the Individual and the Concept of Negative Responsibility

Maximizing the common good encompasses a central limitation—the indifference to the uniqueness of the person. First, in promoting the common good, certain actions that do not advance that end are devalued, even if those actions have intrinsic merit. Second, as Williams

(25) discussed, this position is consistent only if it supports the concept of negative responsibility by holding that we are responsible for consequences we fail to prevent (even when not of our own doing) as well as those caused by our actions. In certain instances this is intuitively obvious. Consider the example of a person who encounters a drowning child. It is difficult to condone the morality of walking away because the person has no relationship to the child; rather, a powerful obligation exists to save the child. One argument is the person’s negative responsibility to promote the general good. However, negative responsibility can be invoked to justify acts that many would deem excessive—for example, to compel highly altruistic acts of charity

(26) or to require actions that compromise the agent’s integrity. The latter issue is highly relevant to our discussion concerning the moral responsibility of clinicians in flawed health care systems. By compelling certain actions, negative responsibility challenges the notion of autonomy by undermining the belief that an individual is “specially responsible for what

he does, rather than for what other people do”

(25, p. 35). As Williams argued, the result is that personal integrity “is rendered as a value more or less unintelligible”

(25, p. 35), as illustrated by his vivid hypothetical example of Jim, a botanist. Surveying a remote jungle, he unexpectedly witnesses a planned execution of 20 innocent peasants caught up in the cruelty of a revolution. Their deaths are to serve as a deterrent to others who oppose the oppressive regime. An officer decides to free 19 hostages if Jim will act as executioner of one of their number. Williams discussed the conflicting moral responsibilities—to commit one murder in order to save 19 human beings, or to refuse and bear indirect responsibility for many more deaths. A utilitarian resolution is obvious—killing one to save the many—but this act violates personal integrity given Jim’s opposition to taking human life, particularly an innocent life.

This case, albeit extreme, shows how imposing one set of values on a person can so conflict with his or her own values as to undermine integrity. That ethical decision making should depend on such procedure is counterintuitive. To expect a person to “step aside from his own…decision” is “to alienate him…from…the source of his action in his own convictions…attitudes within which he is most closely identified. It is thus…an attack on his integrity”

(25, pp. 49–50).

We introduce now a poignant case to illustrate how such integrity may be crushed by policies of a flawed system of health care—in this case by bureaucratic intransigence governed by interests other than those of the patient. A newly graduated psychiatrist (let us call him Dr. Smith) chose to work in a small, rural general hospital in Australia. Among his first patients was Ms. Wing, a 78-year-old woman with severe depression. Notwithstanding prompt treatment with antidepressant medication and supportive care, Ms. Wing’s condition deteriorated rapidly, culminating in a state typified by paranoid delusions and refusal to eat or drink. The situation soon became perilous, and the need for ECT was obvious.

At this point Dr. Smith encountered intractable resistance on the part of the administration. ECT could not be arranged because of “practical factors,” and Ms. Wing would need to be transferred to a psychiatric hospital 120 km away. By this time her physical state was dire. Dr. Smith’s protestations that transfer of such an ill person was tantamount to negligence were to no avail; the administration stood firm. His clinical team supported him inasmuch as all members agreed that Ms. Wing’s physical condition precluded a long journey. Moreover, the move would mean losing the support of family members who were not able to travel with her. A contest of wills followed, and the outcome was a stalemate. In the midst of the battle Ms. Wing’s health declined, and she died 2 days later.

Dr. Smith felt resentful and anguished, convinced that ECT applied promptly not only would have saved his patient’s life but also would have led to alleviation of her psychotic depression, as she had responded well to ECT in the past. His efforts to bring the tragedy to the attention of the regional health authority were frustrated by buck passing and stonewalling. Enraged and embittered, Dr. Smith tendered his resignation, his former eagerness to serve in a remote area entirely squelched.

Personal Integrity and Health Care

The foregoing discussion suggests that a mental health system must adhere to fundamental principles, such as fidelity, in seeking a balance between fairness and efficiency so that its policies not only advance the common good, by expending resources efficiently, but also respect individual claims to care. By definition, such a system necessarily limits clinicians’ decision making; however, it must not do so in a way that undermines integrity. Sabin and Daniels

(27) usefully reviewed features of an ethical health care system. They espoused a “normal opportunity” model, which embraces a balance between fairness and efficiency (although some patients will not get what they want or all they need) in that it is grounded in a sense of justice, derived from Rawls’s concept of fair equality of opportunity

(28). (One of Rawls’s fundamental goals in this classic work was to articulate a theory of social justice superior to that of utilitarianism.)

Sabin

(29) discussed further how clinicians must adopt principles to supplement established codes of ethics in order to create a balance between efficiency and fairness. For example, they should serve as stewards of resources and work for justice in their organizations as they strive to protect patients’ interests. Morreim

(5) echoed this when noting the tension between efficiency and fidelity. A “morally sound” norm of fidelity for her encompassed

ordinary and reasonable care, with the proviso that in times of scarcity, what is reasonable will depend in part on what is available. Beyond this, physicians owe patients their own best efforts, skills, thoughtfulness, and competence. They also owe each patient reasonable efforts to secure needed health resources.… And they owe assistance in combating those rules where they distribute resources unjustly or fail to consider the needs of patients as individuals.

(5, p. 24)

This is more easily proclaimed than applied. More and more systems of health care are flawed because they fail to guarantee fundamental ethical principles or favor provision of care to certain groups of patients and sacrifice the interests of individual patients. Clinicians resorting to dubious strategies to minimize these effects highlight another ominous feature of a flawed system, namely, the manner in which they imperil their own integrity. Handicapped by limited resources, they adopt practices that tax their ability to maintain ethical standards. “Poaching,” for instance, is a way of gaining available resources for patients for whom they are not intended. A common practice is cost shifting, whereby affluent patients are charged higher rates in order to support the needy. “Hoarding” refers to securing resources (which might not otherwise be available) by bending rules required by health systems (e.g., providing unnecessary treatment, such as intravenous hydration in an emergency department, to justify brief hospitalization for patients covered by insurance for inpatient care but who cannot afford the copayment for emergency treatment).

Morreim cautioned that such “gaming” of the system may lead to “fudging, even outright fraud, and in turn compromise integrity”

(5, p. 24). Evidence accumulates that clinicians increasingly resort to these practices. Most doctors in one survey

(30) were inclined to misrepresent a screening test (e.g., a mammogram) as a diagnostic procedure despite any evidence of disease (e.g., a breast lump) in order to obtain third-party funding. They justified their action in terms of consequences by claiming that patients’ welfare was of greater value than truth telling. In another study

(31), one-quarter of the doctors polled reported nonexistent clinical features to gain reimbursement. Most of them had also manipulated reported diagnoses and exaggerated symptom severity to prevent premature discharge from the hospital.

Ethical Implications for the Psychiatrist

At this point, we need to state more specifically than hitherto what we view as a flawed system of health care. We admit that this is a subjective standard, particularly in the allocation of resources to a population with diverse needs, requiring a combination of preventive, short-term, and long-term treatment. However, criteria for what is “good enough” have been widely acknowledged as valid (e.g., an acceptable quality of treatment, fair access to care, guarantee of key ethical principles)

(32). The specifics of a “decent minimum of care”

(7, pp. 348–377;

33) may still be the subject of debate, but it is our position that this is precisely the process needed to establish “good enough” criteria. As Mackie pointed out

(34, pp. 20–27), so-called objective truths depend on evaluation relative to standards established through an interpretive process:

Skating and diving championships, and even the marking of examination papers, are carried out in relation to standards of quality or merit which are peculiar to each particular subject-matter or type of contest, which may be explicitly laid down but which, even if they are nowhere explicitly stated, are fairly well understood and agreed to by those who are recognized as judges or experts in each particular field. (34, p. 26)

In other words, reasoned debate by informed people exercising considered judgments “defines” standards. The process may also be applied to determine what constitutes a good enough health care system. The pioneering effort in Oregon, which integrated treatment of physical and mental illness into a unified system, is one means to establish what is good enough

(35,

36). Judgment can similarly be made about flawed systems.

Another indication as to the adequacy of a health care system is whether the clinician’s integrity is compromised beyond acceptable levels. We agree with Daniels that if a system is to promote communal, as well as an individual’s, needs, there must be a limit on clinicians’ autonomy. Without that they would be unfettered in their decision making concerning resource allocation, which could lead to waste and/or unnecessary treatment and contribute to morbidity and mortality. On the other hand, autonomy can be so circumscribed that communal concerns are promoted at the expense of the basic interests of individual patients, as well as diminution of their legitimate rights, such as confidentiality and informed consent. The clinician’s integrity is then so assaulted that the system is flawed.

We argue that psychiatrists are ethically bound to act in the face of such circumstances. If they shrink from the effort, they become responsible, in part, for adverse effects the system imposes. Their advocacy should accord with Morreim’s guidelines: to provide reasonable care and, when patients are unjustly denied this, to assist them in securing the necessary resources. There are explicit precedents for psychiatrists’ advocacy, especially when fidelity to the patient conflicts with other interests (e.g., opposing a Jehovah’s Witness family’s wish that its child not receive a transfusion)

(7, pp. 130–131). Similar reasoning should apply when the third party is a managed care organization or governmental bureaucracy. At least three options are available to psychiatrists.

The first is for psychiatrists to serve as stewards for resources by working for justice in their organizations and in the health system as a whole—just as in their clinical role they must promote the welfare of patients

(29). For example, psychiatrists should work toward revising criteria of “medical necessity” that they note exert adverse effects on patients, an activity grounded in professional expertise rather than bureaucratic algorithms that neglect clinical reality.

The second is to take political action, either individually or collectively. In this context, Fleck’s thesis

(37) that health resource allocation is not an “economic, managerial, organizational, or technological problem,” but instead “a moral and political problem,” is apposite. This echoes Aristotle’s notion that ethics and political activity are inextricably linked and points to a role for psychiatrists in translating moral values into political realities. The task can be accomplished in manifold ways, including education (of individual patients, their families, or the public at large), lobbying, or seeking public office in order to promote health policy.

Third, psychiatrists can respond as a professional group by shaping an appropriate ethical position to guide action. Codes of ethics are ideal vehicles. Hitherto, professional bodies have only gingerly initiated the task of identifying ethical principles in the area we are addressing. In some cases, reference is by allusion only. For instance, the American Psychiatric Association’s

Principles of Medical Ethics With Annotations Especially Applicable to Psychiatry (38) consigns the matter to the final principle: “A physician shall recognize a responsibility to participate in activities contributing to an improved community.” The annotations that follow provide sensible but slender guidelines. The World Psychiatric Association’s Declaration of Madrid

(39) is equally minimalist in referring to an advocacy role for psychiatrists as societal members—pushing for fair and equal treatment for all. Other medical bodies have similarly been spare in their statements. The Australian Medical Association’s Code of Ethics

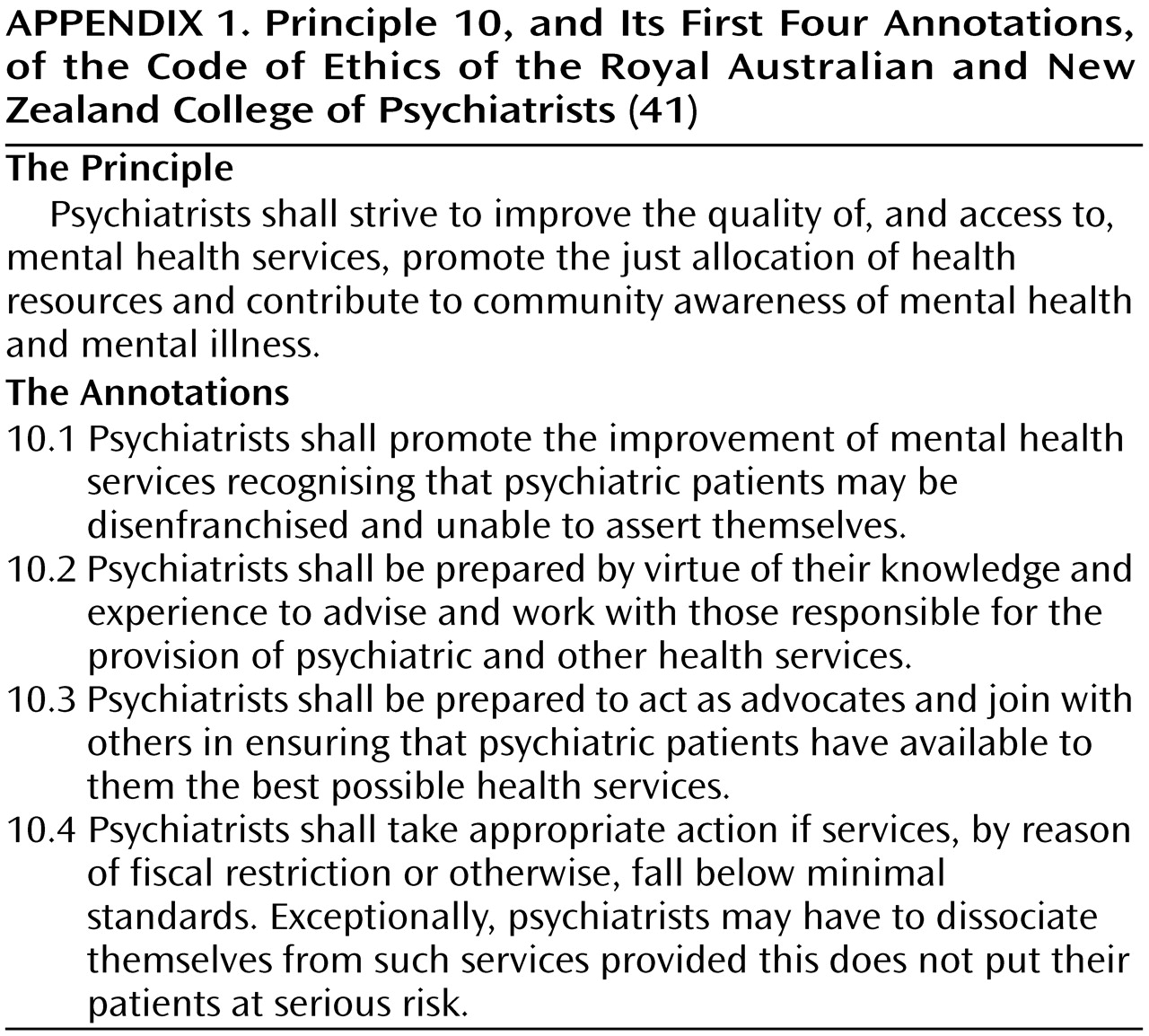

(40) calls on its members to “strive to improve the standards and quality of medical services in the community and more specifically to use special knowledge and skills to consider issues of resource allocation,” but that is as far as it goes. One initiative unusual in its detail and explicitness is that of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists

(41). It shows how psychiatrists as a professional group can weave their societal obligations into a code of ethics and involve themselves in issues involving both service provision and resource allocation. Noteworthy is the progression from the general to the specific (

Appendix 1). Australasian psychiatrists have also promulgated a position statement on mental health services

(42)—a more comprehensive account of these issues. (Copies are available from us on request.)

Predictably, psychiatrists’ attempts to promote good enough services can be thwarted. For example, some managed care organizations threaten to exclude health professionals, an act that can radically hamper their ability to practice, if efficiency standards (e.g., number of patients seen and/or levels of resources expended) are not met. Psychiatrists may obviously opt to extricate themselves from such work conditions, but they do so at the risk of economic vulnerability. This is not a decision most would take lightly even if they had options to practice elsewhere

(43).

If, as Morreim argued, clinicians are not obliged to act in excessively altruistic fashion (e.g., sacrificing income to protect patients against the deleterious effects of a health care system)

(5, p. 21), or if they cannot alter their patients’ situation without incurring personal hardship, the thorny question arises of whether they bear moral responsibility for helping to sustain practices they know are potentially or actually harmful. Does the principle of negative responsibility apply in these circumstances? Or is it too stringent a standard, given that psychiatrists may, by dint of their dependent positions, not have a meaningful voice? Ultimately, the matter revolves around the link between negative responsibility and professional integrity. If they do not act, the result may be what Charlesworth termed “Eichmann-like”—an atmosphere is perpetuated in which clinicians “don’t raise questions…and don’t worry about so-called ethical issues” but instead do as they are told even if that compromises patients’ well-being

(44, p. 109).

The question thus remains: Where psychiatrists are unable to reform a flawed system or resign because of the detrimental effects this would impose on themselves or their patients, are they ethically responsible for the impact of unjust policies? We suggest a threshold exists beyond which they cannot be regarded as free moral agents. A system may be so deficient that it is ethically unacceptable. Psychiatrists are then in a position analogous to that of the botanist Jim, in contrast to the adult’s encounter with an unknown drowning child. When integrity is so violated, it is much harder to embrace the principle of negative responsibility, and it is debatable whether psychiatrists can be held accountable for the shortcomings of the system in which they function. Direct responsibility is mitigated but not if they evade pursuing actions, professional and/or political, to correct wrongs. Indeed, it is through such actions that good enough health care can be accomplished.