The diagnostic criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in DSM-III specified that events were traumatic if they were outside the realm of usual human experience

and would evoke significant distress in the vast majority of people. The finding that a traumatic event will occur at some time in the lives of more than half of the adults in the United States

(1) necessitated revision of this specification. In DSM-IV the exposure criterion was modified into two components. Criterion A1 specifies that the event must represent a serious threat to the self or to others; criterion A2 requires that the initial response to the event involve fear, helplessness, or horror. This change fundamentally reconceptualized trauma exposure, explicitly acknowledging the wide individual differences in immediate response.

There are several reasons to study responses occurring at the time of a trauma and immediately after, a time frame that has come to be called “peritraumatic”

(2). Self-reported peritraumatic responses might explain additional variability in PTSD symptoms over and above the objective trauma characteristic, a view supported by a meta-analysis

(3) that found peritraumatic dissociation to be a better predictor of PTSD than objective trauma characteristics. Given that acute dissociative responses occur in the context of elevated distress

(4) and that not everyone who experiences high levels of distress during trauma has a dissociative response, peritraumatic distress may have predictive value over and above peritraumatic dissociation. Indeed, it has been proposed that peritraumatic anxious arousal enhances trauma-related memory

(5) and sensitizes the neurobiological systems implicated in the pathogenesis of PTSD

(6). This hypothesis cannot be fully investigated without valid and reliable instruments for assessing peritraumatic emotional distress.

With the intent of creating an inventory of immediate responses to trauma, we reviewed the literature and found studies reporting heightened emotional distress and bodily arousal as concomitants of trauma exposure. Examples included feelings of personal life threat

(7), fear

(8,

9), feelings of helplessness

(9,

10), horror

(9), guilt and shame

(9,

11), anger

(9,

12), loss of bowel and bladder control

(11,

13), and shaking, trembling, and increased heart rate

(8,

14–

16).

In this article we present the psychometric properties of the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory as developed in a study group of police officers; we also examine both reliability and validity of the instrument. We show that peritraumatic distress scores are positively associated with two measures of PTSD symptoms, even after partialling out variance accounted for by general psychopathology or by peritraumatic dissociation. Finally, we extend those results to a study group of civilians.

Results

Trauma Exposure and Index Events

Exposure severity for the officers’ index events was as follows: 322 (45.9%) personally experienced a critical incident, 308 (43.9%) were witness to an incident, and 72 (10.3%) heard of the exposure of a close friend or relative to a critical incident. The incidents included accidents (N=8, 1.1%), natural disasters (N=4, 0.6%), physical assaults (N=157, 22.4%), sexual assaults (N=17, 2.4%), illnesses/injuries or deaths (N=449, 64.0%), harassment/threats (N=44, 6.3%), and other critical incidents (N=16, 2.3%).

Exposure severity for the index event in comparison subjects included personally experiencing a critical incident (N=182, 60.5%), witnessing a critical incident (N=49, 16.3%), and hearing of the exposure of a close friend or relative to a critical incident (N=70, 23.3%). The index events included accidents (N=11, 3.7%), disasters (N=8, 2.7%), physical assaults (N=52, 17.3%), and sexual assaults (N=15, 5.0%), illnesses/injuries or deaths (N=156, 51.8%), combat (N=4, 1.3%), harassment/threats (N=38, 12.6%), and other critical incidents (N=17, 5.6%). Most index events were not of recent origin: the mean time since the incident for officers was 6.64 years (SD=5.16); for the comparison subjects it was 8.83 years (SD=6.50). The groups did not differ in terms of social desirability (t=0.64, df=1,001, p>0.05).

Peritraumatic Distress Inventory Psychometrics

The Peritraumatic Distress Inventory is derived from an earlier scale, the 23-item Peritraumatic Emotional Distress Scale

(28). Items were revised by a panel of six researchers and clinicians working in the field of PTSD (A.B., D.S.W., S.R.B., T.C.N., C.R.M.) and violence (J.F.). Nine items were retained and three were reformulated. Eleven items were dropped on the basis of a consensus that they did not apply to a wide array of critical incidents. Nine new items were added on the basis of a literature review and the clinical experience of the panel members, for a total of 21. In a preliminary report, we examined the factor analytic structure of this pool of 21 items, which yielded three factors

(29). Because one of these factors included a method confound and several of its items did not occur strictly within a peritraumatic time frame, that factor was dropped, along with its items.

We performed a new principal factor analysis using the remaining set of 13 items. Squared multiple correlations were used as initial communality estimates. Estimates were iterated. An oblique promax rotation was performed on the factors with an eigenvalue greater than 1. The first factor (negative emotions) had seven items, and the second (perceived life threat and bodily arousal) had six. Factors 1 and 2 had eigenvalues of 3.00 and 1.98, explaining, respectively, 23% and 15% of the total variance (38%). Factors 1 and 2 explained 60% and 40% of the common variance, respectively, and were modestly correlated (r=0.20). Use of a rotated orthogonal solution did not change the number of factors, their item content, and item loadings. Confirmatory factor analysis was used to replicate the factor solution in the comparison group of non-police-officers; the major goodness-of-fit indexes were in the adequate-to-good-fit range.

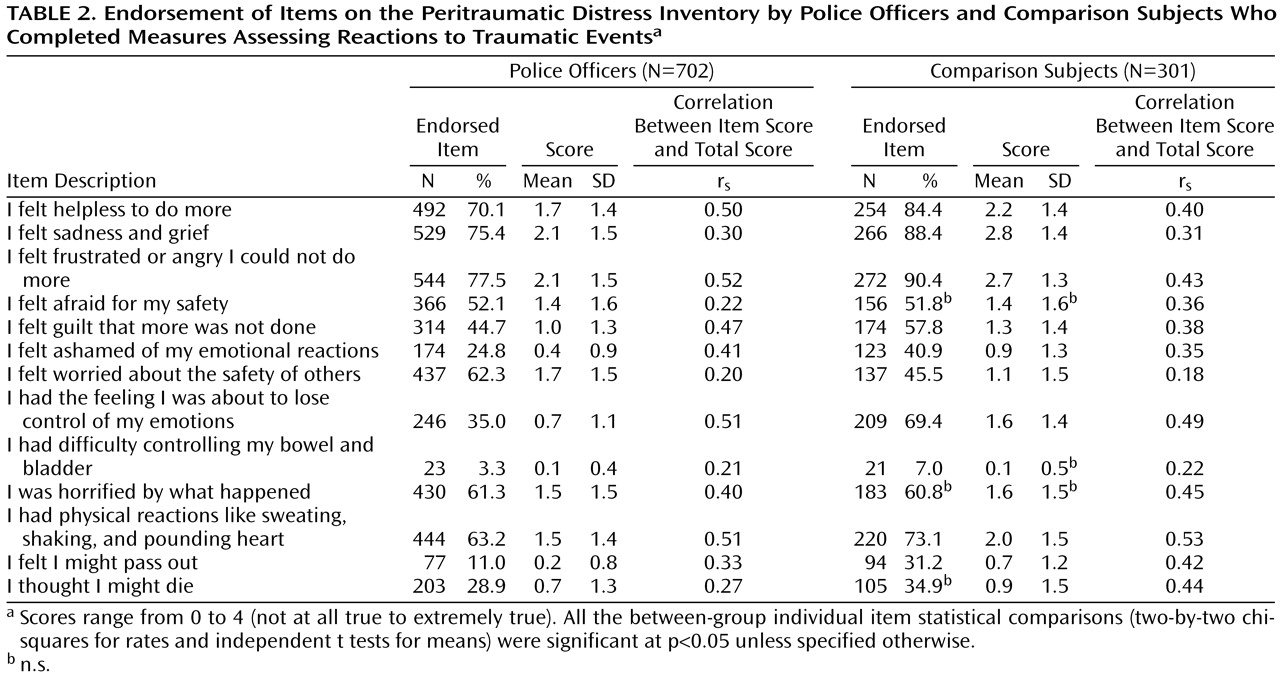

As shown in

Table 2, the most frequently endorsed items in both groups were feeling frustrated or angry, feeling sadness and grief, and feeling helpless. The least endorsed items in both groups were losing control of one’s bowel and bladder and passing out. Most officers (N=639, 91%) and comparison subjects (N=277, 92%) endorsed one or more of the three items included in DSM-IV criterion A2 (fear, helplessness, or horror). Overall, comparison subjects more frequently endorsed Peritraumatic Distress Inventory items, and their mean level of endorsement was higher than that of the officers. One exception was that the police officers more often reported worrying about the safety of others.

We next examined the distribution of the responses and temporal stability of Peritraumatic Distress Inventory scores. In both groups, most item distributions were positively skewed. However, the distribution of total Peritraumatic Distress Inventory scores was symmetrical in both study groups. The standardized coefficient alpha for the total Peritraumatic Distress Inventory score was 0.75 in officers and 0.76 in comparison subjects. A subgroup of officers (N=71) was retested on the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory an average of 391 days (SD=130, range=80–585) after initial measure completion. The test-retest correlation coefficient was 0.74, indicating very good temporal stability. A modest decrease in mean score across time was observed (t=2.76, df=70, p<0.01; d=0.25).

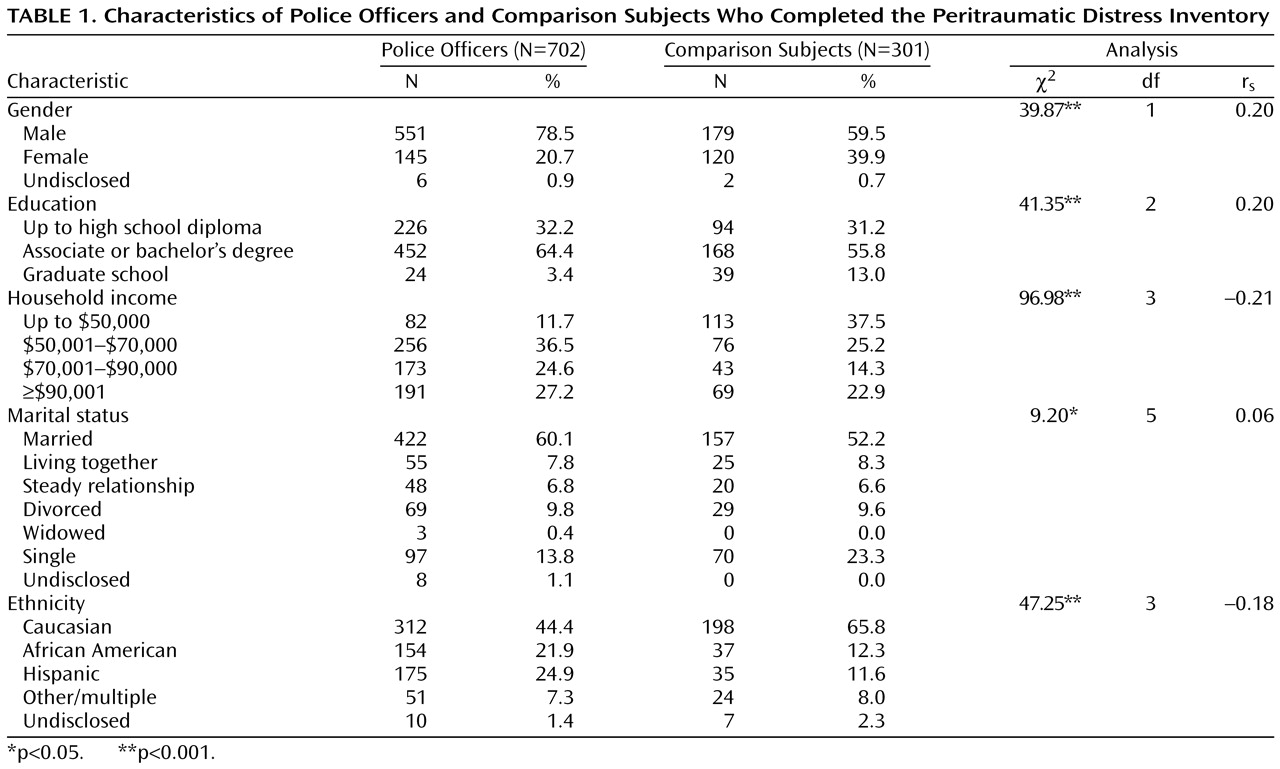

Sociodemographic Differences on the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory

To test for the effects of age, gender, ethnicity (Caucasian or other) and group (officer or comparison subject), we conducted a two-by-two-by-two analysis of covariance with age as a covariate among the participants with complete sociodemographic data (N=984). We could not test the comparison of African American and Hispanic subjects because of small cell sizes for the comparison group. The overall model was significant (F=9.11, df=8, 984, p<0.001). The age covariate was not significant (F=0.16, df=1, 984, p>0.05). No main effect was found for ethnicity (F=0.11, df=1, 984, p>0.05). Main effects were found for gender (F=11.67, df=1, 984, p<0.001) and for group (F=46.41, df=1, 984, p<0.001). Women had higher scores on the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory than men (mean=1.44, SD=0.74, compared with mean=1.26, SD=0.64) (d=0.27), and so did the comparison subjects (mean=1.52, SD=0.69) compared with the police officers (mean=1.17, SD=0.64) (d=0.53). The only significant interaction term was the gender-by-group term (F=5.78, df=1, 984, p<0.05). There was no difference between groups among men, but female officers scored lower (mean=1.37, SD=0.65) than their civilian counterparts (mean=1.67, SD=0.76) (d=0.43).

Convergent and Divergent Validity of the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory

Among police officers, the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory correlated with conceptually related measures, such as peritraumatic dissociation (r=0.59, p<0.001), Civilian Mississippi Scale score (r=0.46, p<0.001), and the intrusion (r=0.47, p<0.001), avoidance (r=0.47, p<0.001), and hyperarousal (r=0.42, p<0.001) subscales of the Impact of Event Scale—Revised. These relationships persisted even after we partialled out the variance attributable to the SCL-90-R index of general psychopathology (r=0.24 to r=0.53, p<0.001) and the Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences Questionnaire index of peritraumatic dissociation (r=0.26 to r=0.34, p<0.001).

The Peritraumatic Distress Inventory scores correlated modestly, or not at all, with conceptually different measures, such as social support (r=–0.11, p<0.05), physical health (r=–0.15, p<0.05), and time elapsed since the critical incident (r=–0.03, p>0.05). Examination of convergent and divergent validity was repeated in the comparison group with results similar to those found in the police officers.

Discussion

Many of the police officers and comparison subjects reported feelings of helplessness, sadness and grief, and frustration and anger; physical reactions such as sweating, shaking, and a racing heart; and being horrified after traumatic exposure. The occurrence and magnitude of such reactions was positively associated with two widely used measures of PTSD symptoms. These results echo the findings of other investigators

(8–

12,

14–

16), most of whom, however, focused on a single type of peritraumatic distress response or did not control for general psychopathology or peritraumatic dissociation.

The Peritraumatic Distress Inventory was internally consistent and stable over time. Although most Peritraumatic Distress Inventory items had good to excellent correlations between item and total scores, a few, such as worry about the safety of others, did not. This finding is consistent with the notion that learning about another person’s trauma, in contrast with directly witnessing it, often leads to PTSD. Difficulty controlling bowel and bladder and feeling like passing out were endorsed by fewer participants; these items also had lower item-total correlations, as was found in another study

(13). It remains to be seen if such items are more frequently endorsed in other traumatized groups.

It is worthwhile to note that all of the main findings obtained in the group of police officers were replicated in the comparison subjects who were exposed to a variety of traumatic events. This increases confidence in the results and suggests that the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory is applicable to studies of trauma in the general population.

We found moderate differences in responses related to gender and group membership. The women in the comparison group reported more peritraumatic distress than the female police officers, but the men in the comparison group did not differ from the male officers. More research will be needed to determine if female officers are more resilient to trauma than their civilian counterparts.

The most important limitations of the current study involve its cross-sectional design with retrospective report of peritraumatic distress. Recall may decay with time or be biased by current symptom levels

(30). Another limitation relates to the requirement that participants complete the PTSD symptom scales in relation to a single event. The potential contribution of critical incidents other than the index event to current self-report of PTSD symptoms is an important and underexplored issue that is particularly salient in studies of highly exposed emergency services personnel.

Compared with peritraumatic dissociation, peritraumatic distress is an understudied phenomenon in the chain of events that may lead to the development of PTSD. The Peritraumatic Distress Inventory provides a tool to examine models of the genesis of PTSD, including the hypothesis that peritraumatic dysphoric arousal may enhance trauma-related memory and sensitize neurobiological systems implicated in the pathogenesis of PTSD.