Comorbidity of panic attacks with affective disorders is a frequently reported phenomenon

(1–

3) with significant clinical implications

(4,

5). Frequent comorbidity suggests but does not prove a common etiology. Shared clinical responsiveness to antidepressants and certain antimanic agents

(6) and overlapping pathophysiologic hypotheses

(7) lend some support to a common etiology for panic and affective disorders. Evidence for a common genetic etiology for bipolar disorder and panic disorder comes from a family study in which risk of panic with bipolar disorder was examined in families ascertained for a bipolar disorder linkage study

(8).

In that study, a subset of 57 families with a high prevalence of bipolar disorder had an unusually high rate of panic disorder. For families in which the proband had experienced any panic attacks, first-degree relatives with bipolar disorder had a three-fold greater rate of panic disorder than did those from families in which the proband had not experienced panic attacks (36% versus 10%). Relatives with bipolar disorder in these families at high risk for panic were more likely than their counterparts in other families to have hypomania (bipolar II disorder) rather than mania (bipolar I disorder or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type). The subjects in the bipolar disorder linkage study

(8) with recurrent major depressive disorder had a lower-than-expected rate of panic comorbidity of only 3%, compared to 18% for subjects with bipolar disorder. Relatives in the families at high risk for panic were less likely to have a substance abuse diagnosis than were the relatives of probands without panic attacks.

The observation that some families at high risk for a disorder demonstrate a pattern of clinical features that differentiates them from other families with that disorder has proven to be of use in examining the genetics of complex disorders. A gene for breast cancer was discovered after data for families with early-onset breast cancer and a high vulnerability to ovarian cancer were analyzed separately from data for families with late-onset breast cancer; evidence for genetic linkage was obscured when data for all families were analyzed together

(9). Thus, an overly inclusive definition of disease, or phenotype, may obscure a finding of genetic linkage by combining two or more different genetic disorders into one category. The breast cancer story suggests that such clinical markers of heterogeneity may be subtle or may be inessential to the core definition of the clinical syndrome.

With this consideration in mind, the major conclusion of the bipolar disorder linkage study that panic comorbidity marked a genetically distinct subtype of bipolar disorder

(8) was tested in 28 study families for which there was evidence of genetic linkage on chromosome 18

(10). When genetic linkage results were stratified by proband panic diagnosis, linkage scores varied significantly across sets of families, as predicted

(11). Families at high risk for panic were linked to markers on the long arm of chromosome 18, and families of probands without panic showed no evidence for linkage. The opposite pattern has been found in other regions of the genome (unpublished 1999 data of D.F. MacKinnon, et al.).

Although these findings might seem to be sufficient grounds for exploring stratification by familial panic comorbidity in genomic studies, the statistical cost can be high

(12). A misspecified phenotype would miss a genetic linkage or association by including genetically heterogeneous disorders in the same category. An overly conservative scheme that included only a few families could miss a true genetic linkage or association because of insufficient statistical power. Two main limitations in the existing evidence for the genetic heterogeneity of bipolar disorder on the basis of panic comorbidity are 1) that the finding of the bipolar disorder linkage study

(8) has not been replicated (nor has a failed replication been reported) and 2) a simple family study approach, such as the approach used in the bipolar disorder linkage study

(8), cannot adequately demonstrate familial risk unless the potentially significant confounding effects of other kinds of interfamilial heterogeneity can be accounted for.

To address these questions about panic as a marker of bipolar disorder genetic heterogeneity, we analyzed diagnostic data from the NIMH Bipolar Disorder Genetics Initiative, a four-site collaboration from 1989 to 1997 that gathered data from families for a linkage analysis of bipolar disorder. More than 200 new families are included in the present analysis. We used logistic regression analysis with generalized estimating equations to examine the risk of panic comorbidity as a function of being a first-degree relative of a proband with mania (bipolar I disorder or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type) and panic attacks. The analysis controlled for potential confounding effects, such as sex and affective disorder subtype. Our principal aim was to reexamine the hypothesis that comorbid panic attacks are a phenotypic marker of genetic heterogeneity among families segregating bipolar disorder.

Method

Ascertainment

Background and detailed methods for the NIMH Genetics Initiative are described elsewhere

(13). The initiative has yielded 203 families for this analysis. The initial set of 97 families was ascertained both systematically from hospital admissions and nonsystematically from volunteers and referrals. Families that were ascertained systematically were included if 1) the proband had been impaired or incapacitated with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder; 2) the proband had at least one available first-degree relative with bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder with recurrent major depression, or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type; and 3) either the proband or the second relative had at least two living siblings age 18 years or older. In an attempt to minimize intrafamilial heterogeneity, families were excluded if both of the proband’s parents had bipolar I disorder and/or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. Inclusion of families that were ascertained nonsystematically required a somewhat higher threshold: the proband had two first- or second-degree relatives with bipolar I disorder (at most one with schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type), as well as two other available affected relatives with a recurrent affective disorder, including recurrent major depressive disorder or bipolar II disorder. The subsequent set of 106 families was enrolled with the uniform criterion of bipolar I disorder in the proband plus bipolar I disorder or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type, in a first-degree relative, with no further restrictions on family size or composition. Eleven probands, who were thought at screening to have bipolar I disorder, were ultimately assigned a best-estimate diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. These probands and their families are among the 203 families included in this analysis. None of these families overlapped with families in our earlier study

(8).

Assessment

After giving written, informed consent, all subjects included in this analysis were administered the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies

(14). Interviews were conducted by trained interviewers either in-person or by telephone. At the Johns Hopkins site all interviews were conducted by one of five psychiatrists; at other sites interviewers had clinical experience in nursing or social work or were experienced, trained research interviewers. Best-estimate final diagnoses were made by two noninterviewing psychiatrists on the basis of the interview, available medical records, and family history data. In case of disagreement, a third psychiatrist made the final best-estimate diagnosis.

Affective disorder diagnoses were assigned by using both DSM-III-R and Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC)

(15), while only DSM-III-R criteria were used for other diagnoses. To allow for comparison with our previous work, we employed the RDC for major affective disorder diagnoses for this analysis. Diagnoses of panic disorder and other nonaffective disorders were based on DSM-III-R criteria.

Data Sources

Item-by-item demographic and interview data and all best-estimate diagnoses were entered from each site into a central computer maintained by a contractor. The data set used for the present analysis was downloaded from the central site in October 1998. Diagnostic data were obtained from several sources. Affective disorder diagnoses were taken from the pedigree files created for genetic analyses. Comorbid diagnoses were retrieved from the best-estimate final diagnosis file, and other information about symptoms and demographic characteristics was taken from the pedigree and interview data files. No assumptions were made as to the primacy of the affective or panic disorder diagnosis.

Data were available on 1,856 individuals who were interviewed, assigned best-estimate affective disorder diagnoses, and included in the database for the NIMH Bipolar Disorder Genetics Initiative. Thirty-four members of three pedigrees were excluded because the family data were incomplete (i.e., no information about the panic disorder diagnosis of the proband was available or an insufficient number of first-degree relatives with bipolar disorder had been interviewed), leaving a total of 1,822 individuals from 203 pedigrees (203 probands and 966 first-degree relatives).

Analysis

Pearson’s chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to test group differences in diagnosis and sex. Student’s t test was used to compare differences in age. Hypothesis testing was performed with logistic regression analysis. The regression analysis included data for the 500 first-degree relatives affected with either a bipolar disorder (bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder with recurrent major depression, or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type) or recurrent major depressive disorder. The decision to include relatives with recurrent major depressive disorder was made because we observed a high rate of panic comorbidity in these relatives. However, the analysis controlled for bipolar versus unipolar diagnoses because of a prior observation of differences in panic comorbidity between subjects with bipolar diagnoses and those with unipolar diagnoses

(8). The analysis also controlled for female sex, because this characteristic was also previously found to be distributed unevenly across families with high and low risk for panic

(8). On the basis of findings in the bipolar disorder linkage study

(8), we combined families of probands with panic attack and families of probands with panic disorder into one group defining a binary variable for familial panic risk. A best-estimate panic disorder diagnosis in first-degree relatives was the dependent variable. The analysis was performed with generalized estimating equations

(16), which take into account potential correlations between data for multiple members of the same family. Unless otherwise noted, p<0.05 was assumed to define statistical significance.

Results

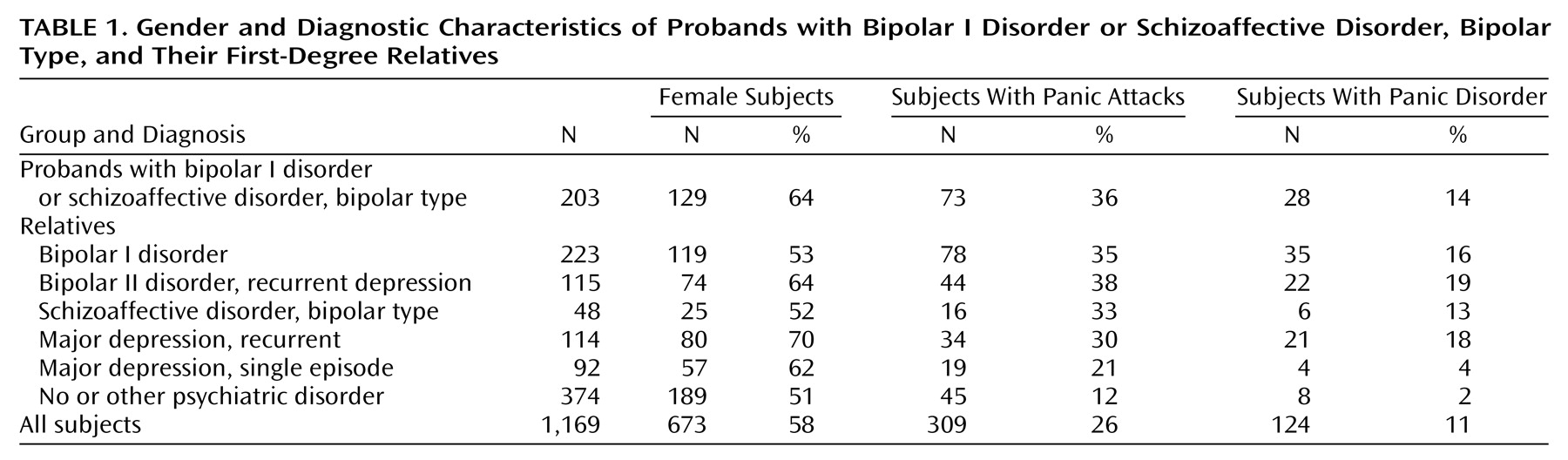

Panic disorder was strongly associated with affective disorder in this study group. Ninety percent of the 124 probands and first-degree relatives with panic disorder also had a recurrent major affective disorder (

Table 1). Only two relatives had panic disorder without comorbidity. Conversely, panic disorder was a frequent diagnosis in family members with recurrent major affective disorder, at a rate of 17%, and occurred with roughly equivalent frequency in subjects with bipolar and recurrent major depressive disorder diagnoses. More than a third of individuals with a bipolar diagnosis or recurrent major depressive disorder had experienced at least one panic attack. Panic disorder occurred disproportionately in female relatives. Eighty percent of subjects with panic disorder were female.

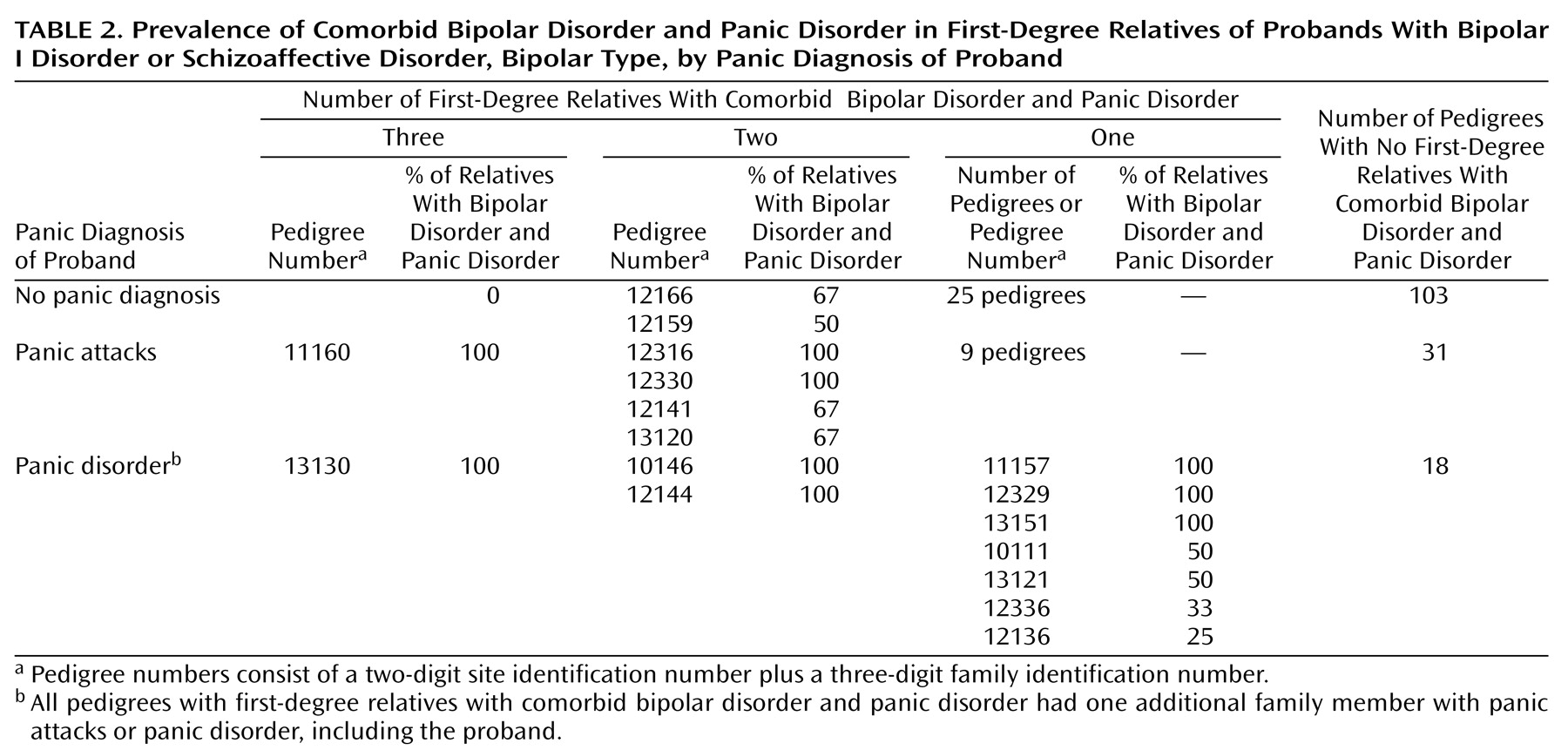

Panic disorder was diagnosed more frequently in the relatives with bipolar disorder in the families of probands with panic than in the relatives of probands without panic.

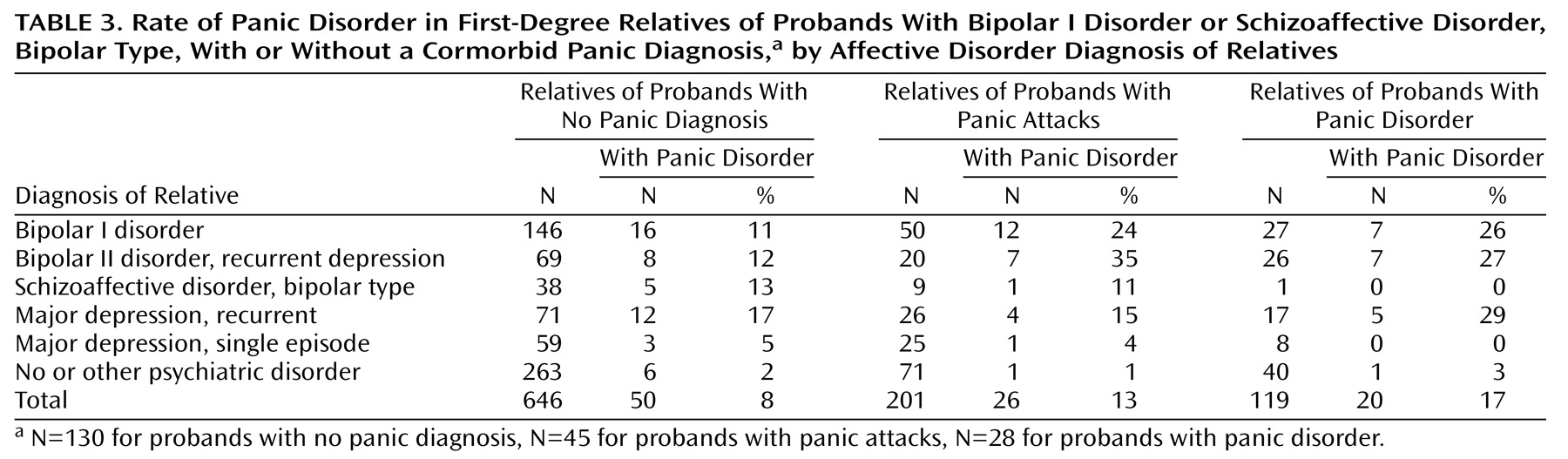

Table 2 charts the number and percentage of relatives with bipolar disorder (excluding probands) who were affected with comorbid panic disorder per pedigree per family group. One in three families of the probands with panic attacks or panic disorder had one or more relatives with comorbid bipolar disorder and panic disorder, compared to one-fifth of the families of probands without panic. Eight of the 73 families of probands with panic had two or more relatives with comorbid bipolar disorder and panic disorder (not including the proband), compared to two of the 130 families of probands without panic (p<0.005, Fisher’s exact test). Among relatives with bipolar I disorder or bipolar II disorder with recurrent major depression, panic disorder occurred with twice the frequency in relatives of probands with panic attacks or panic disorder as in relatives of probands without panic (

Table 3). The few subjects with panic disorder and no recurrent major affective disorder were distributed at rates of 1%–3% across the three family groups.

There was no difference across groups in the rate of comorbid substance abuse/dependence diagnoses, with the exception of sedative/hypnotic abuse/dependence, which was relatively uncommon yet significantly more frequent in the relatives with bipolar disorder in the families of probands with panic than in the relatives of probands without panic (7% versus 2%) (p=0.02, Fisher’s exact test).

Ages at onset of bipolar disorder (mean=19.4 years, SD=8.9, versus mean=21.6 years, SD=9.9) (t=2.07, df=363, p<0.05) and panic disorder (mean=22.7 years, SD=10.6, versus mean=26.7 years, SD=12.1) (t=1.9, df=110, p=0.06) were somewhat lower in relatives with bipolar disorder in the families of probands with panic than in relatives of probands without panic, although the age at interview was nearly identical (mean=43.2 years, SD=17.0, versus mean=43.3 years, SD=15.1) (t=0.05, df=237, p=0.96).

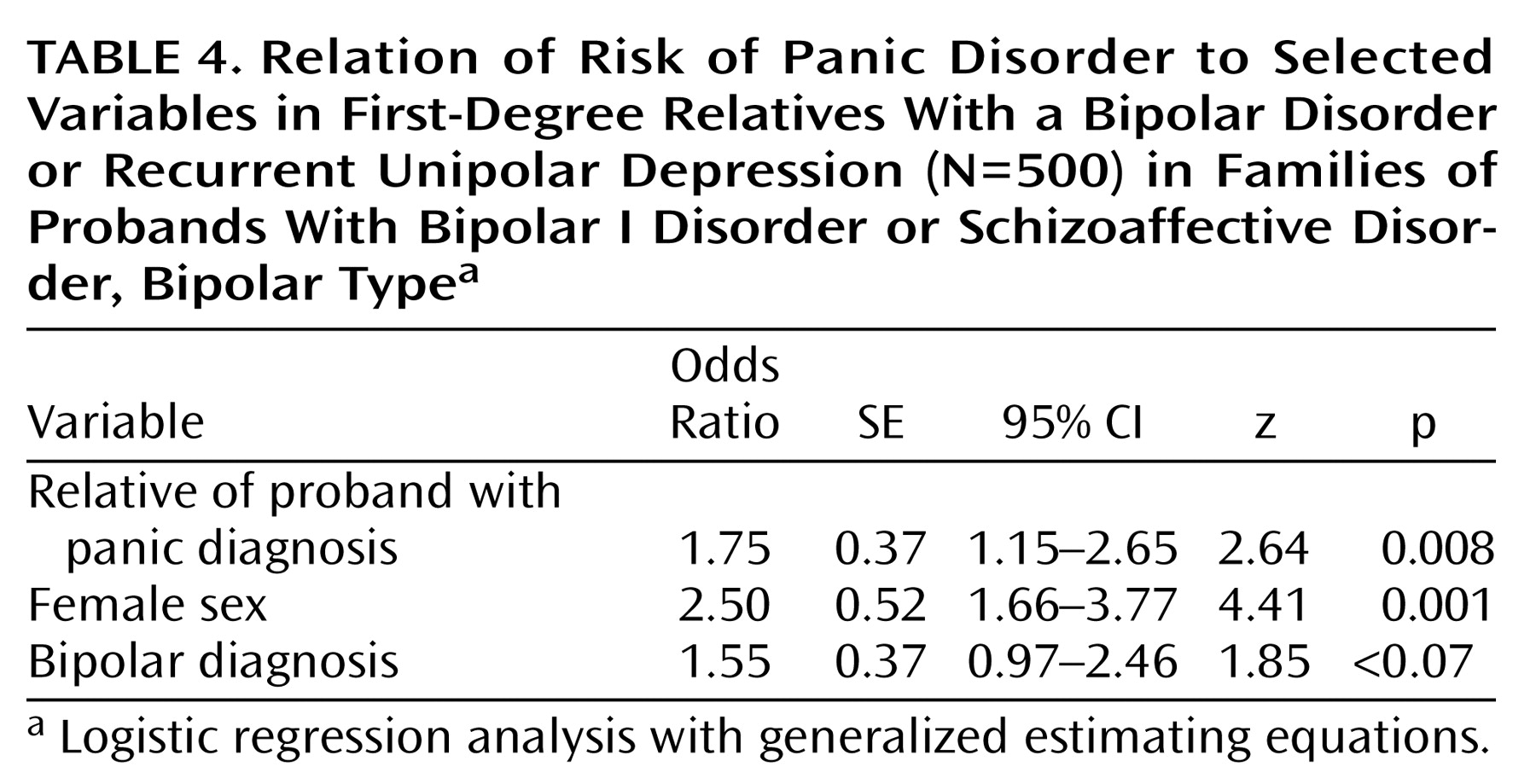

A logistic regression analysis examining the risk factors for panic disorder in first-degree relatives and controlling for sex and bipolar versus unipolar diagnosis in the relatives showed that having a proband with panic was associated with higher risk for panic disorder in the relatives (

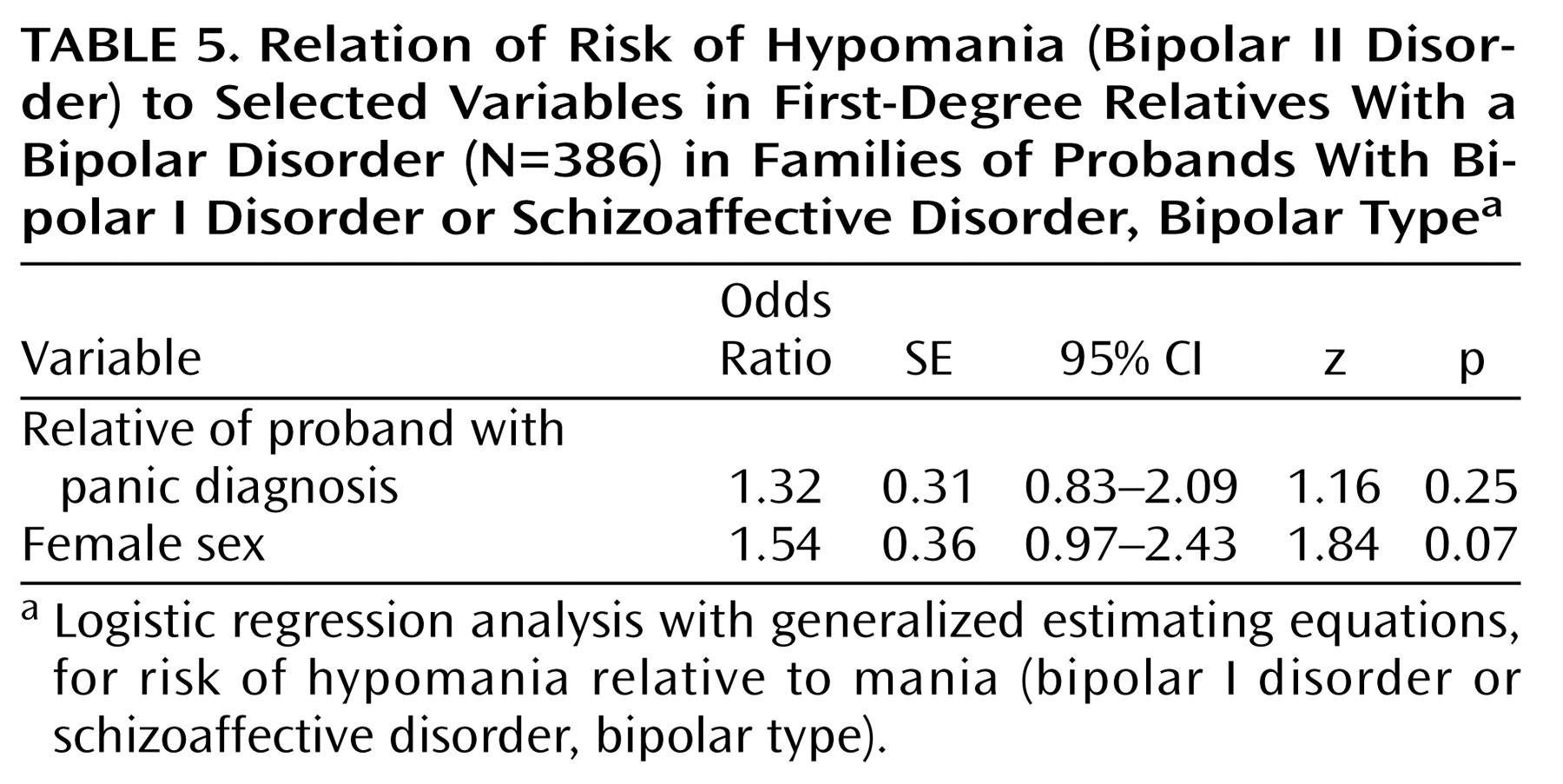

Table 4). In this model, female sex was the most potent risk factor, raising the risk for panic disorder by a factor of 2.5 over the risk for male relatives. Having a proband with panic increased the risk of panic disorder in first-degree relatives with recurrent affective disorder by a factor of 1.75. Having bipolar disorder as opposed to recurrent unipolar depression increased the risk of panic disorder by a factor of 1.55. To examine whether panic in the proband predicted a higher proportion of hypomania (bipolar II disorder) versus mania (bipolar I disorder or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type) in the relatives, we ran a separate analysis on data for the 386 first-degree relatives with a bipolar disorder. In this analysis, hypomania (as part of a diagnosis of bipolar II disorder) was the outcome variable, and the analysis controlled for female sex and panic in the proband. Families of probands with panic disorder tended to have more relatives with bipolar II disorder; 48% of the relatives with bipolar disorder in these families had bipolar II disorder versus 27% in other families. However, the logistic regression analysis failed to demonstrate an elevated risk for bipolar II disorder over bipolar I disorder in the families of probands with panic when female sex was included in the model (

Table 5).

Discussion

Familial bipolar disorder is associated with elevated risk for panic disorder. Family members with bipolar disorders are at significantly higher risk for panic disorder if the proband with bipolar disorder in the family has had panic attacks. The results of this analysis confirm and extend the major findings of a prior analysis of panic comorbidity in a similar and independent set of families ascertained at Johns Hopkins University for a bipolar disorder linkage study

(8). The rate of panic disorder comorbidity in family members with bipolar disorder was remarkably similar across the studies. Most important, both studies found that panic disorder comorbidity is to some degree familial: the proband’s experience of any panic attacks raises the risk for panic disorder in the first-degree relatives with bipolar disorder. The findings are extended in the present study by controlling for the influence of sex on panic comorbidity, by examining the contribution of bipolar subdiagnosis to panic risk in individuals with affective disorder, and by accounting for other sources of correlation between family members by using generalized estimating equations. We also confirmed evidence from the bipolar disorder linkage study

(8) and from an epidemiological survey

(17) that panic disorder occurs disproportionately in women.

Several variables of possible interest were omitted from the analysis. Although mean ages at the onset of bipolar disorder and panic disorder were different across families, the differences were not great enough to provide a clean division between early and late onset. Given that the mean age at the interview was much later than the mean age at the onset of the disorder, age at onset was not judged to be a likely source of bias. A diagnosis of substance abuse was not factored in, despite being a finding of interest in the bipolar disorder linkage study

(8), since visual inspection of the data revealed no trend in substance abuse rates across the families in the NIMH study.

These results leave a key question unresolved. What are the boundaries of the bipolar/panic phenotype? The answer hinges on three additional questions concerning the genetic model, the definition of the affective disorder phenotype, and the definition of the panic disorder phenotype.

Our findings best fit a complex genetic model. A simple heterogeneous genetic model, with a single gene and full expression (or penetrance) in a subset of families, would account for only the six families in which all individuals with bipolar disorder also had panic disorder. The existence of discordant families, in which some family members with bipolar disorder had panic and some did not, implies variable gene expression and/or oligogenic inheritance. In a model of variable expression, the bipolar/panic gene(s) may produce simple bipolar disorder in some relatives, simple panic disorder in others, and comorbid bipolar disorder and panic disorder in the rest. Discordant patterns of bipolar disorder and panic disorder within a family might also be produced by a combination of genes; i.e., a panic gene segregating in some family members may lead to phenotypic expression of panic only in combination with one or several genes conferring vulnerability to bipolar disorder. Discordance might also be produced by nongenetic mechanisms; i.e., the pathologic process leading to comorbid bipolar disorder and panic may occur downstream from the molecular etiology for bipolar disorder. Manic or depressive episodes may, for example, increase the risk for panic attacks generally, via nonspecific sympathetic activation. Alternatively, subjects who have bipolar disorder but not panic may have an inherited or acquired protection against panic or, in some cases, may be vulnerable but may not have experienced sufficient provocation.

Vulnerability to panic disorder in relatives with unipolar depression remains an uncertain factor in the identification of a bipolar/panic phenotype. In contrast to the findings of the Johns Hopkins University bipolar disorder linkage study

(8), in which panic was rarely seen with recurrent major depressive disorder, the recurrent major depressive disorder subjects in the families with bipolar disorder in the NIMH study had a panic disorder rate similar to that found for subjects with unipolar depression in most other population and family studies

(18). Panic disorder appeared to be more common in the relatives with unipolar depression than in those with a bipolar disorder in the families of probands with panic disorder, but it was less common in the relatives with unipolar depression in the families of probands with panic attack (

Table 3). Overall, subjects with bipolar disorder had a modestly elevated risk for panic compared to subjects with recurrent major depressive disorder, in analyses controlling for female sex and panic in the proband (

Table 4). Although this difference did not reach statistical significance, taken with the results from the bipolar disorder linkage study

(8), it is consistent with a trend toward greater panic comorbidity in family members with bipolar disorder versus unipolar depression.

The remaining question is whether the bipolar/panic phenotype includes individuals with panic attacks below the threshold for a diagnosis of panic disorder. Inspection of the data for this study shows that such loosening of the phenotype does not alter our main finding, although it does expand the pool of families who appear to be at risk for panic. The problem remains that some families have relatives with bipolar disorder who are discordant for panic attack. An alternative approach for defining the boundaries of the panic phenotype in families with a high prevalence of bipolar disorder is to use symptom provocation to reveal latent panic vulnerability. It has been shown that panic-free relatives of panic disorder patients have a panic response when exposed to inhaled carbon dioxide

(19). Patterns of latent panic vulnerability in family members with bipolar disorder may reveal whether panic vulnerability in families with a high prevalence of bipolar disorder is the result of general or nongenetic activation of anxiety mechanisms, of a specific, partially penetrant gene, or of a combination of genes.

Using family study methods, we have confirmed our hypothesis that risk for panic disorder in families segregating bipolar disorder is a familial trait. Questions remain of how this risk for panic is transmitted. Further investigation in molecular genetics and physiologic endophenotypes may help elucidate shared etiologies and pathophysiologic mechanisms of bipolar disorder and panic disorder.