Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is unique among anxiety disorders in that it is defined in the context of exposure to an extremely stressful traumatic event. Recent experience has shown that individuals vary markedly in their tendency to experience posttraumatic stress symptoms

(1,

2). In fact, considerable research has been focused on delineating characteristics of the traumatic stressor that increase its propensity for causing PTSD. Within uniform types of trauma (e.g., combat), greater duration or intensity of exposure to the trauma tends to increase risk for PTSD (i.e., a dose-response relationship is evident)

(3–

6). Across different types of trauma, differences in associated risk for PTSD are also evident. Sexual trauma and combat, for example, are associated with very high conditional risks for PTSD

(7–

10). In general, events that involve the element of interpersonal assault (e.g., rape, violence by an intimate partner, other violent crime) carry higher risks for PTSD than events that lack this element (e.g., motor vehicle accidents, natural disasters)

(8,

11–13).

Although characteristics of the traumatic stressor have been shown to influence risk for PTSD, these fail to explain much of the variance in PTSD rates among exposed persons. This has generated interest in individual differences that may influence PTSD susceptibility. Among such factors, most studies have shown that female gender

(5,

6,

10,

14–17) and low IQ

(18,

19) increase risk for PTSD following trauma exposure. In addition, a number of studies have shown that some premorbid personality characteristics (e.g., neuroticism)

(16,

20,

21) and preexisting anxiety or depressive disorders

(7,

22–24) increase risk for PTSD. The latter findings have been extended to include a family history of anxiety or depressive disorders

(25–

28), raising the possibility of genetic susceptibility factors for PTSD

(29–

31).

Support for genetic influences on PTSD symptoms comes from twin studies. In a small twin study of anxiety disorders (fewer than 50 twin pairs were included), PTSD was found only in co-twins of probands with anxiety disorders

(32). The other published twin study of which we are aware provides the most compelling evidence for a genetic component to PTSD vulnerability. This is the Vietnam Era Twin Registry study of 4,042 male-male veteran twin pairs (2,224 monozygotic and 1,818 dizygotic pairs)

(4,

33). This study showed that genetic factors account for approximately 30% of the variance in PTSD symptoms, even after differences in trauma exposure between twins are taken into account

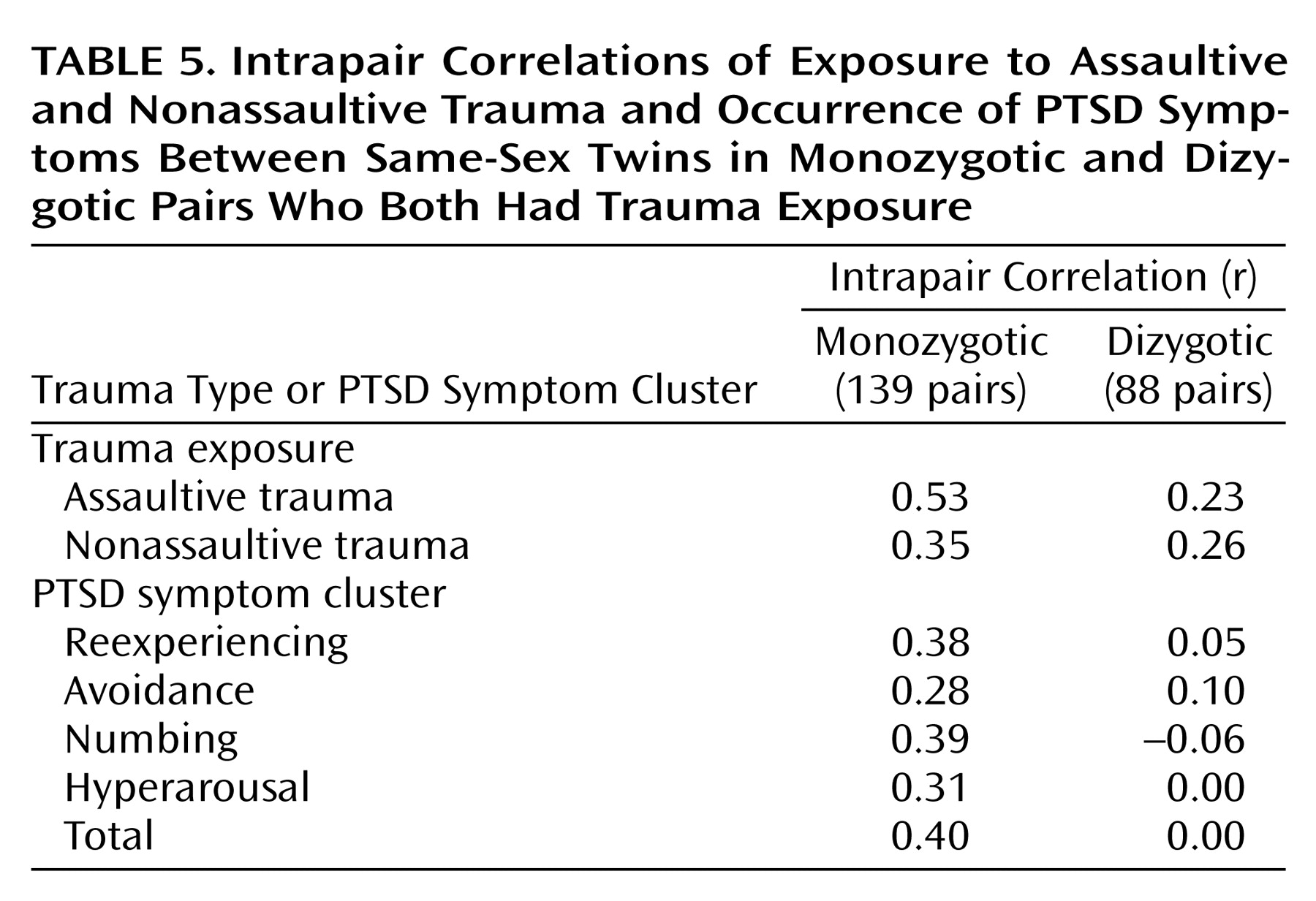

(33). This study also demonstrated genetic influences on extent of trauma exposure

(34), highlighting the fact that risk for PTSD must be considered as the outcome of dual processes: risk for exposure to traumatic events, followed by risk for PTSD symptoms following exposure. Risk factors for these two processes may, to some extent, be shared and may involve pretrauma personality characteristics

(35).

A recent meta-analysis of the genetic epidemiology of anxiety disorders

(36) failed to include PTSD, undoubtedly because of the paucity of data on this topic. In fact, to the best of our knowledge, there are no published twin studies of PTSD symptoms beyond the aforementioned, widely cited Vietnam Era Twin Registry study

(4,

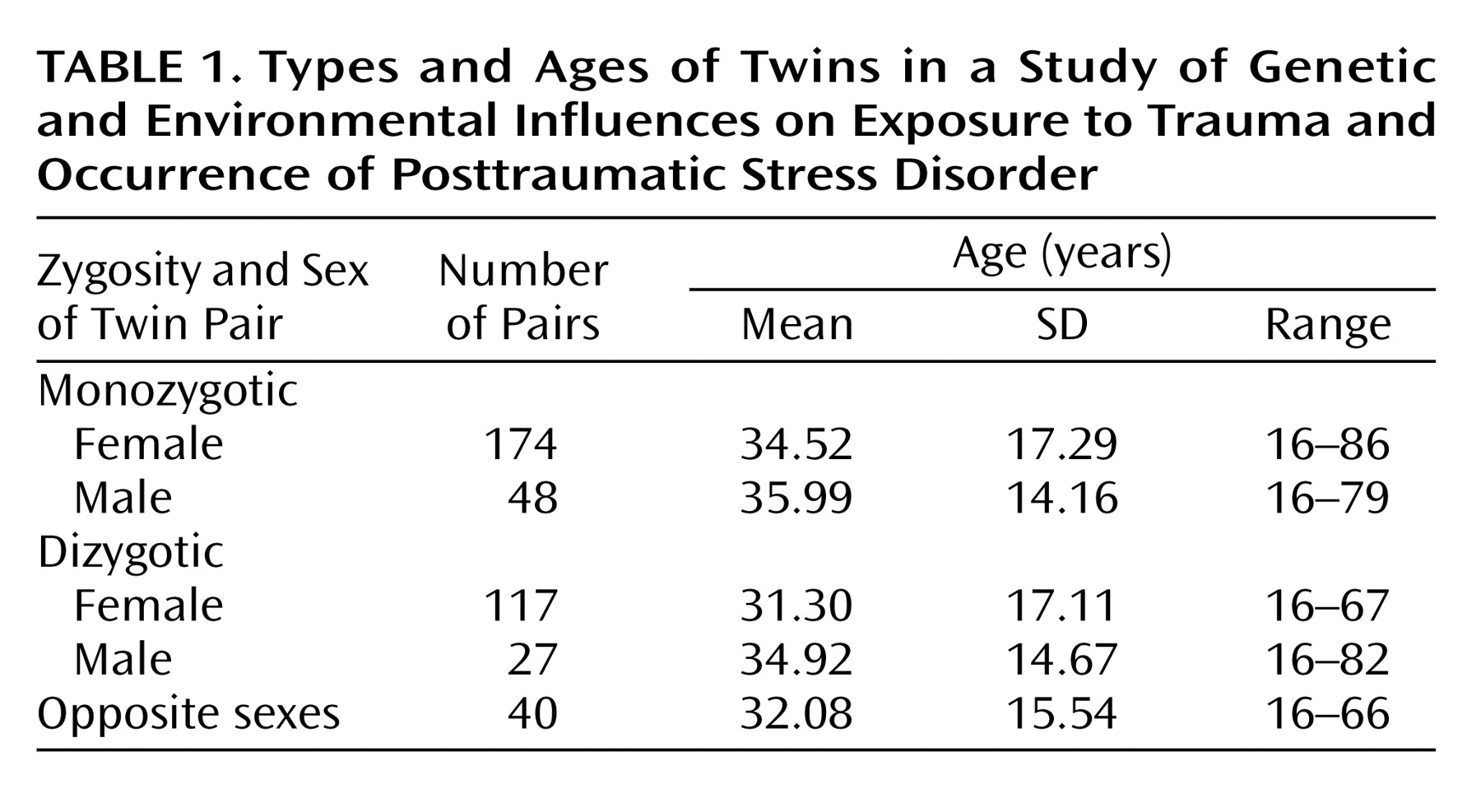

33–35). That study included exclusively male combat veterans, meaning that there are no data on heritability in women or on traumatic stressors other than combat. The purpose of the present study was to expand our understanding of the heritability of trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms into a broader context, by including female twin pairs and surveying a broad range of traumatic events.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the heritability of trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms outside of the context of military trauma. Moreover, we believe this is the first study to do so in a group that includes women. Our study is subject to numerous limitations. Most notable among these are the small number of subjects; a low proportion of men; the volunteer nature of the subjects (rather than randomly sampled community subjects), which may limit its representativeness; and our reliance on self-report measures (yielding quantitative indices of exposure and symptoms) rather than direct interviews (which might have yielded qualitative diagnoses).

This latter aspect of our study deserves closer scrutiny. Relying on quantitative measures, when many subjects provide information about the trait(s) of interest, provides us with sufficient statistical power to make stable parameter estimates even in the absence of a huge study group (i.e., thousands of subjects). Lacking diagnostic information (e.g., DSM-IV diagnoses of PTSD), we measured related traits (e.g., PTSD symptoms) that we assume enable us to make inferences about the disorder(s) of interest. In some cases, such as social phobia, where it is clearer that the disorder behaves as if it were, indeed, the extreme end of a normally distributed trait (i.e., social anxiety), this supposition has empirical support

(48,

49). But in the case of PTSD, this assumption is unproven, and the relevance of our findings to the clinical realm must be considered in light of this uncertainty. At this juncture, we hope that our findings will stimulate further hypothesis testing in study groups for which information about both symptoms and disorders is available.

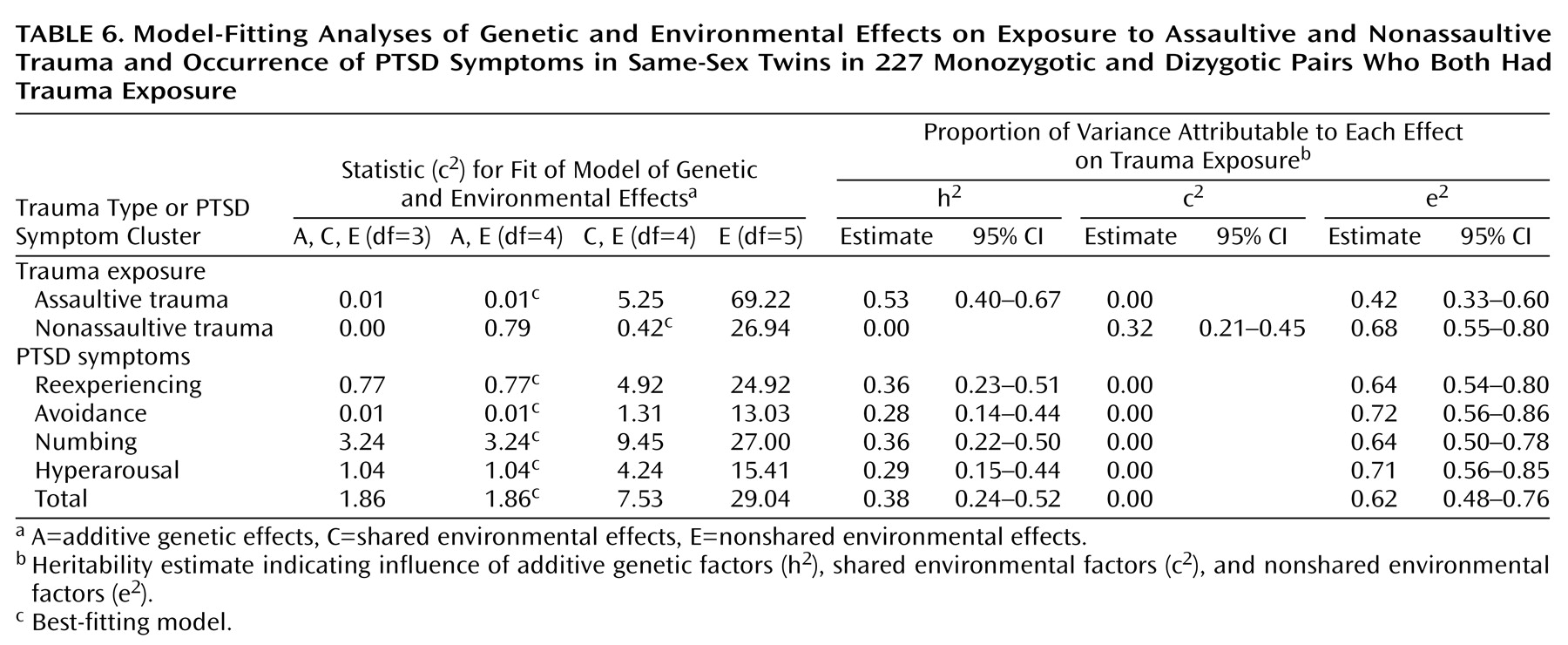

With these constraints in mind, let us consider our findings and their possible implications. As noted by Kendler

(50), “all heritability estimates are specific to a population with a range of environmental exposures” (p. 108). It is therefore reassuring to find that our heritability estimates for PTSD symptoms come remarkably close to those derived from an exclusively male group of combat veterans from the Vietnam Era Twin Registry

(33). These two studies provide an insufficient base from which to extrapolate the heritability of PTSD in other countries and circumstances, but they provide a starting point from which to test this empirically

(50).

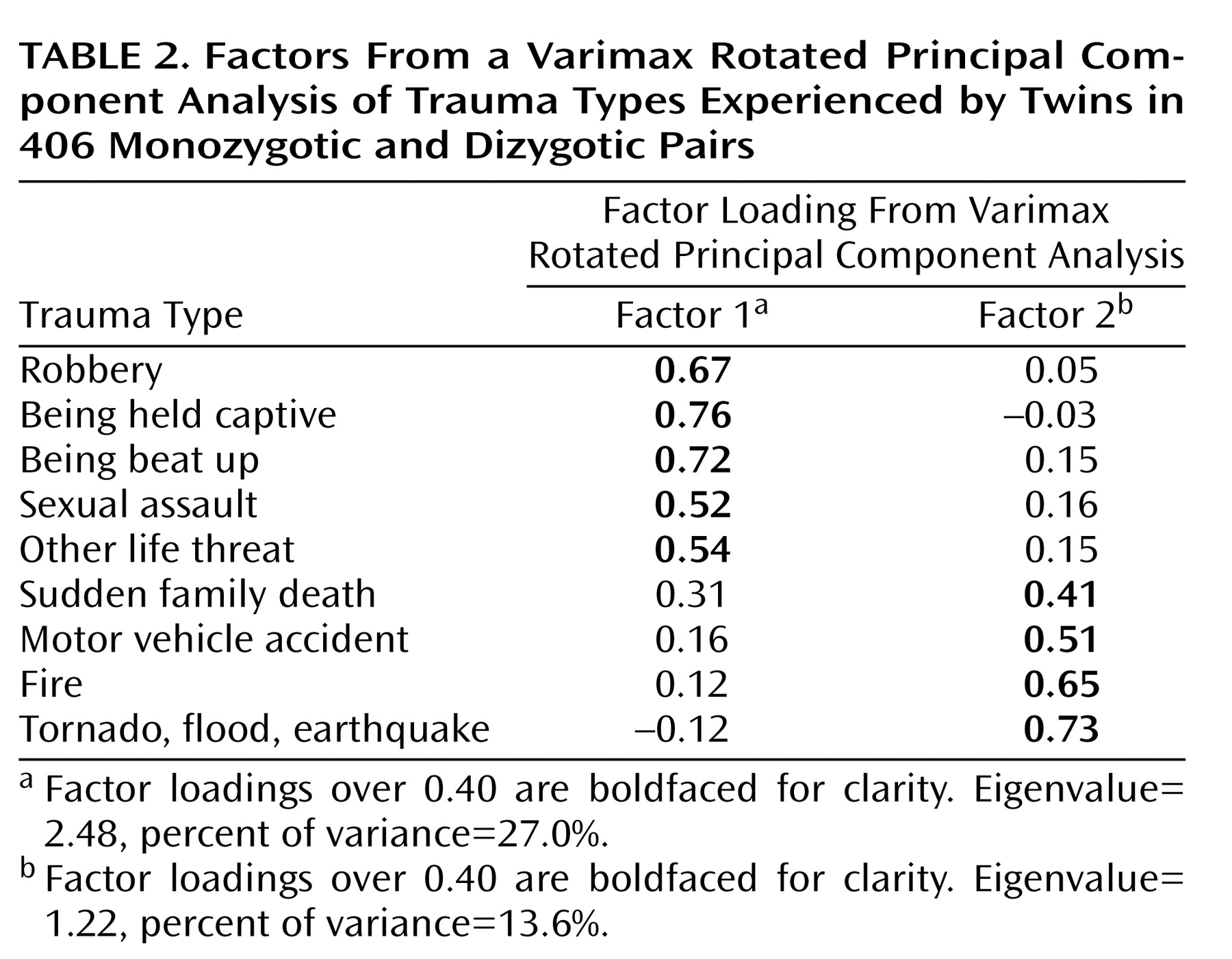

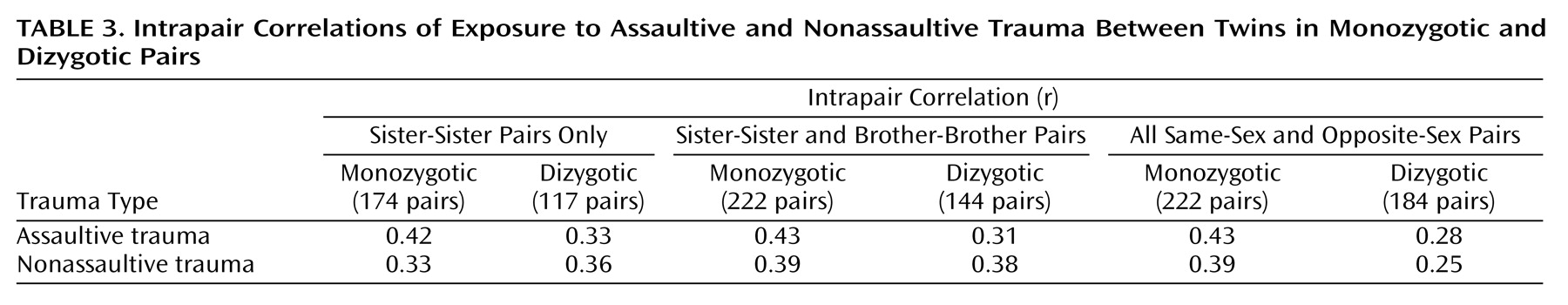

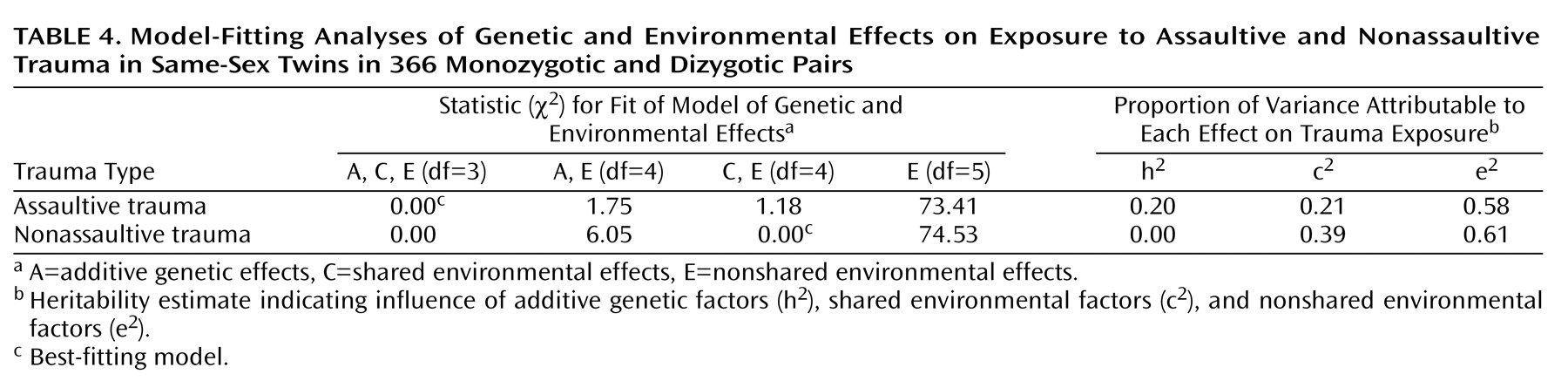

In this group of twins we were also able to show that exposure to certain classes of trauma (e.g., violent crime) is influenced by both genetic and environmental (shared and nonshared) factors, whereas other classes of trauma (e.g., motor vehicle accidents and natural disasters) are influenced exclusively by shared environmental factors. The notion that individual differences in event proneness are, in part, genetically determined is not new. It is now well established that genetic factors can be associated with particular kinds of environmental exposures, including life events

(51,

52), and our findings may be an example of an individual’s genetically determined behavior leading him or her to seek out or engender particular environmental responses. Our number of subjects is insufficient to permit us to declare with certainty that certain kinds of life traumata are genetically determined and that others are not. But our findings are suggestive that violent interpersonal or assaultive trauma and other forms of nonviolent or “anonymous” trauma differ in their genetic influences. This is a hypothesis that can be further tested in other larger, population-based samples.

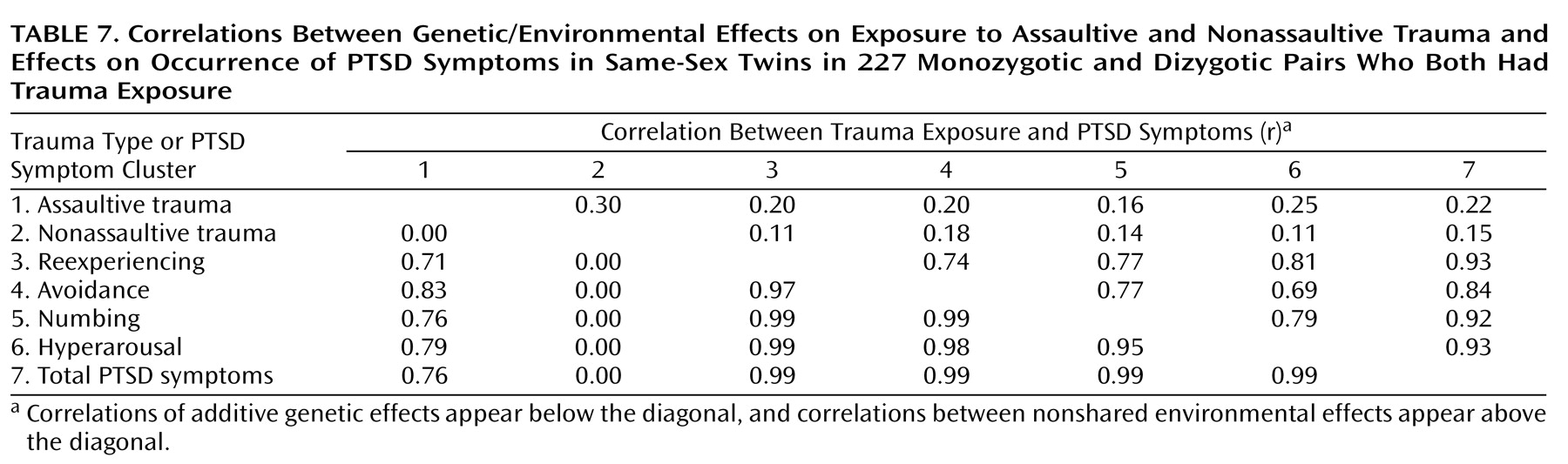

Given the moderate heritability of most other forms of anxiety

(36), it should probably come as no surprise that PTSD symptoms behave similarly. Probably the most interesting part of our study, then, is the finding that genetic influences on trauma exposure and on subsequent PTSD symptoms are substantially overlapping. This raises the question of the pathways and mechanisms by which genes exert these dual influences. One possibility is that genetic influences on “PTSD proneness” might be mediated through personality traits (e.g., neuroticism) that would predispose an individual to assaultive trauma and subsequent PTSD. Simply stated, this model would posit that an individual’s genetically influenced propensity toward neuroticism would lead the individual to experience more anger and irritability, making that person 1) more likely to get into fights (thereby increasing the risk of experiencing assaultive traumata) and 2) more likely to become highly emotionally aroused as a result of experiencing such traumata (thereby increasing the risk for PTSD symptoms). Recently published data from a large twin study by Kendler and colleagues

(53) do, in fact, provide evidence that neuroticism is associated with an increased risk for exposure to some kinds of traumatic events. Personality traits other than neuroticism, however, may also play a role. In the Vietnam Era Twin Registry study, which included only men, preexisting conduct disorder (which might be considered an early manifestation of antisocial traits) was a risk factor both for trauma exposure and for subsequent PTSD symptoms

(35). Given that our study included predominantly women, the possibility that different personality traits influence trauma exposure and PTSD susceptibility in men (e.g., sociopathy) and women (e.g., neuroticism) should be strongly considered.

Future research in this area would benefit from considering (and measuring) some of the individual differences purported to increase risk for PTSD (e.g., IQ, neuroticism, sociopathy) as possible determinants of these genetic effects. Even at this level of analysis, the possibility of gene-environment interactions must be considered. For example, genetic influences on behaviors that reduce social support

(54), a known risk factor for PTSD

(16,

23,

55,

56), might drive the increased risk for PTSD symptoms.

Given the near certainty that susceptibility to PTSD symptoms is a complex trait, large numbers of subjects will be required to detect the influence of what are likely to be many genes each of small effect size

(57,

58). To date, an association with the dopamine type 2 (D

2) receptor

(29) is the only published genetic finding on PTSD of which we are aware, and a second study

(30) failed to replicate this association. Twin studies such as this have the potential to help define what phenotypes should be the focus of genetic investigation. Our findings suggest that genetic influences on PTSD are probably mediated through a causal pathway that includes genes that simultaneously influence personality (i.e., exposure proneness) and PTSD symptoms following exposure. Identification of these factors and understanding of the mechanisms by which they elicit PTSD will enhance the likelihood that future gene-hunting expeditions in this area will produce robust, replicable results.