In the early aftermath of the Holocaust, an array of neuropsychological problems was described in survivors, including anxiety, sleeplessness, and poor concentration and memory. The severity and persistence of these symptoms led to the idea that the “Concentration Camp Syndrome” was an organic brain syndrome associated with premature aging and dementia

(1). Despite the passage of over 50 years, a considerable proportion of Holocaust survivors still suffers from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other neuropsychological consequences of the Holocaust

(2,

3). The question arises as to whether these survivors have memory impairment and whether it is associated with PTSD or aging.

Explicit and implicit memory performance were studied in Holocaust survivors and healthy Jewish adults with no Holocaust exposure. Explicit memory requires conscious, effortful recollection

(15). It is critically dependent on the hippocampus and sensitive to the effects of stress and aging

(7,

16–18). Implicit forms of memory, such as procedural memory and priming effects, do not depend on conscious recollection and are relatively insensitive to aging and hippocampal impairment

(7,

17). Therefore, we hypothesized that Holocaust survivors with PTSD would have poorer explicit, but not implicit, memory performance than comparison subjects and that performance differences would be more marked with advanced age.

Results

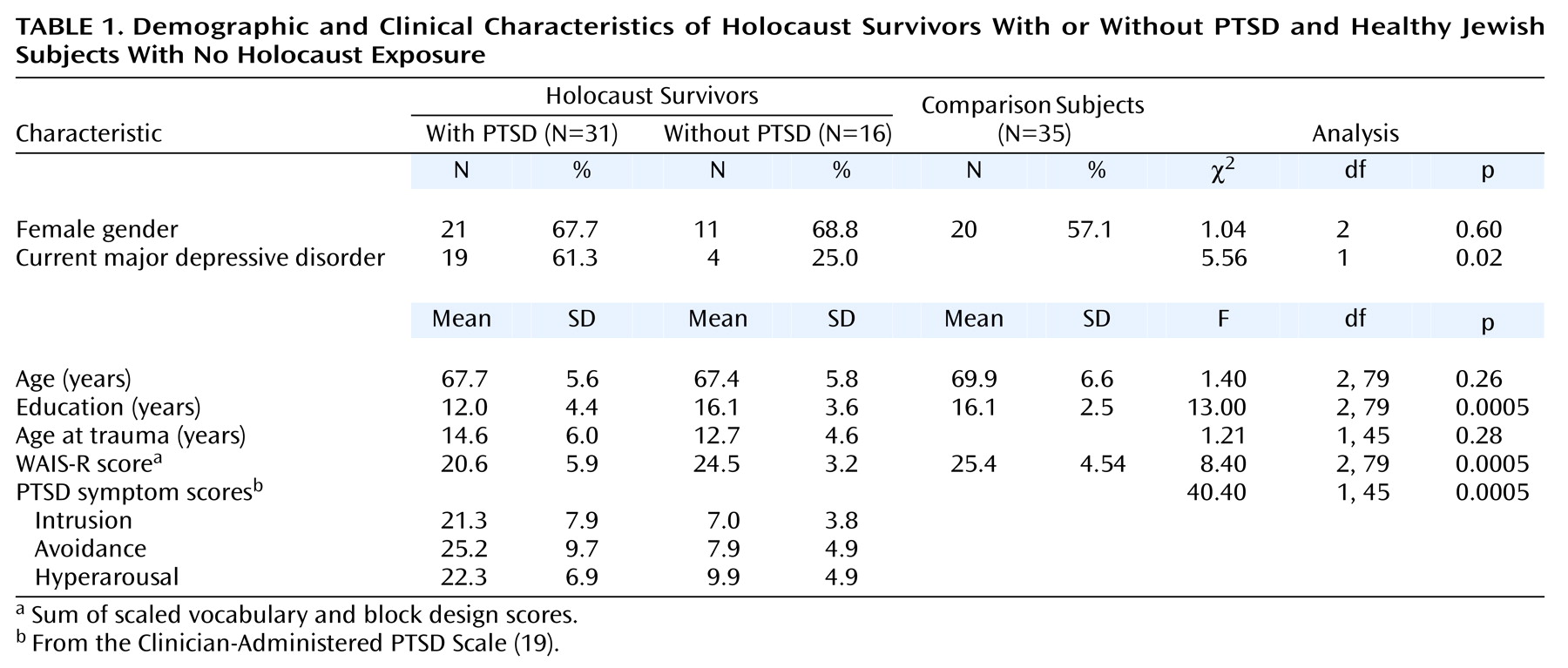

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the three groups are shown in

Table 1. There were 52 women (63%) and 30 men (37%), with a mean age of 68.6 years (SD=6.1, range=57–85). The groups were similar in age and gender distribution. They differed significantly in education level and in the WAIS-R scores (the sum of the scaled vocabulary and block design scores). This score provide an estimate of full-scale IQ; however, the age norms for estimated IQ from this score are only available as high as age 74. On the basis of these norms and using this upper age limit norm for the 13 subjects who were 75–85 years of age, the corresponding estimated IQs were 101.8 (SD=16.5) for the PTSD group, 112.9 (SD=9.2) for the no PTSD group, and 114.8 (SD=12.6) for the nonexposed group. The PTSD group had significantly lower WAIS-R scores than did the no PTSD group (p=0.004; d=0.83) and the nonexposed group (p<0.0005; d=0.91). The PTSD group had significantly fewer years of education than did the no PTSD group (p<0.0005; d=1.04) and the nonexposed group (p<0.0005; d=1.14). The no PTSD and nonexposed groups did not differ in years of education (p=0.998; d=0.02) or on WAIS-R scores (p<0.84; d=0.22). Among Holocaust survivors, those with PTSD were more likely than those without PTSD to meet criteria for major depressive disorder, and they scored significantly higher on the three PTSD symptom cluster scores. The PTSD and no PTSD groups did not differ in age at traumatization.

There was an overall group difference in psychotropic medication use: 19.4% (N=6) of the PTSD, 25.0% (N=4) of the no PTSD, and 2.9% (N=1) of the nonexposed subjects were receiving psychotropic medication (χ2=6.1, df=2, p<0.05). (The one nonexposed subject was receiving meprobamate as a muscle relaxant.) Medication types included antihypertensives (36.6% of the entire group [N=30 of 82]), lipid-lowering medication (14.6%, N=12), thyroid supplement (14.6%, N=12), estrogen-based hormone treatment (13.4%, N=11), gastrointestinal medication (12.2%, N=10), and medication for benign prostatic hypertrophy (2.4%, N=2). There were no significant group differences in the use of these medications (all χ2≤2.7 and p≥0.25).

The associations of gender, current major depressive disorder, and medication use with paired-associate recall performance were assessed (all df=78). Low-associate and high-associate recall were not significantly associated with gender (r=–0.01, p<0.90 and r=0.13, p<0.24, respectively), current major depressive disorder (r=0.02, p<0.83; r=0.14, p<0.22), or psychotropic medication (r=–0.06, p<0.63; r=–0.07, p<0.55). Although use of gastrointestinal medication was inversely associated with high-associate recall (r=–0.22, df=78, p<0.05), the groups did not differ in the use of this medication (χ2=0.88, df=2, p<0.65). None of the other classes of medication were associated with paired-associate recall at the p≤0.05 level.

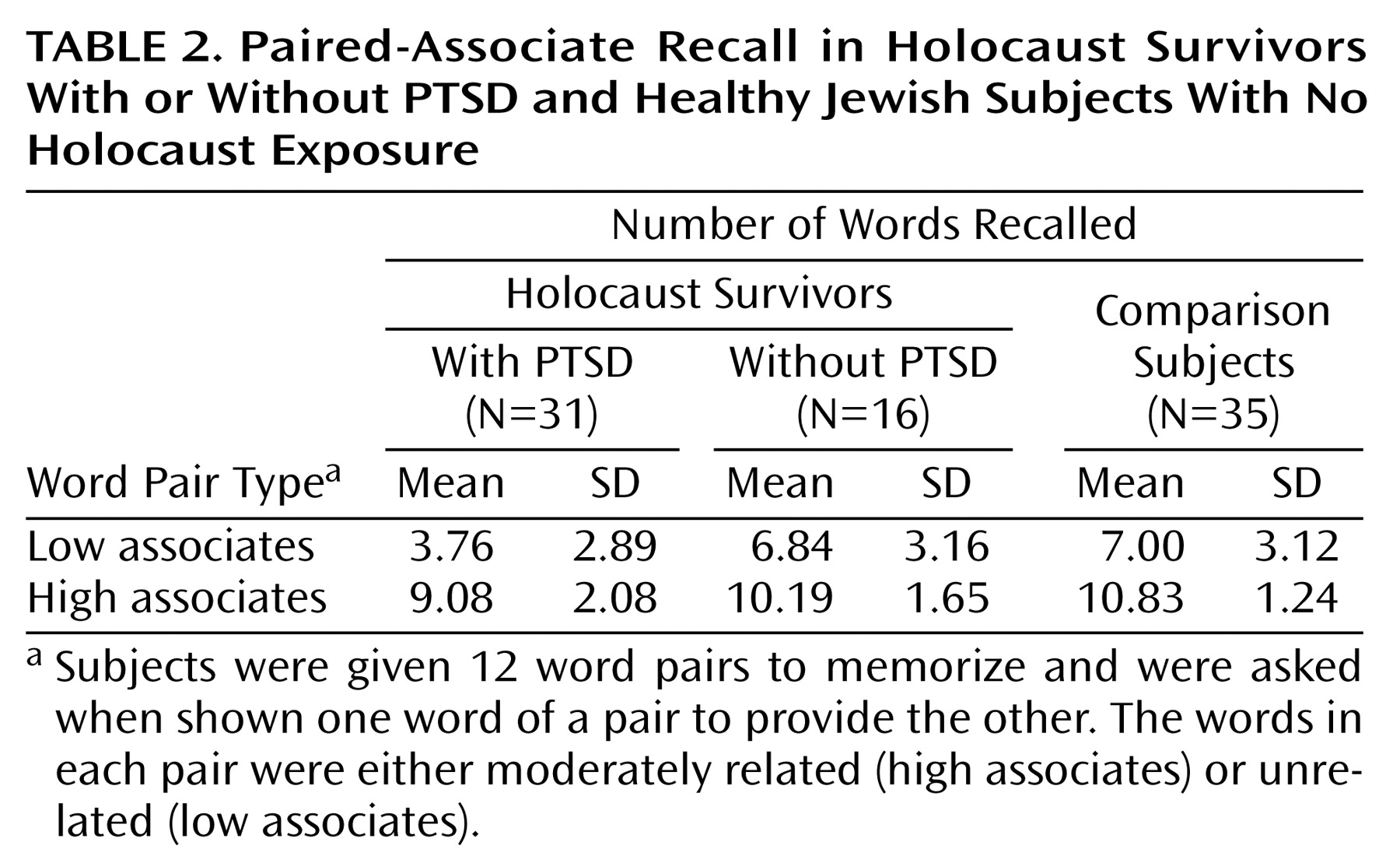

Paired-associate recall results are shown in

Table 2. In the low-associate condition, there was an overall significant group difference (F=10.62, df=2, 79, p<0.0005). Analysis with Tukey’s honestly significant difference revealed that the PTSD group scored significantly lower than did the no PTSD group (p=0.004; d=1.02) and the nonexposed group (p<0.0005; d=1.08). The no PTSD and nonexposed groups did not differ (p<0.99; d=0.05). The mean recall in the PTSD group corresponded to a low (20th to 25th) percentile of the no PTSD and the nonexposed groups. Frank cognitive impairment was defined as a performance level at or below the fifth percentile of the comparison groups. With this criterion, 25.8% (N=8) of the PTSD group were impaired relative to the no PTSD group and 35.5% (N=11) were impaired relative to the nonexposed group.

There was a significant group difference in high-associate recall (F=8.97, df=2, 79, p<0.0005). Analysis with Tukey’s honestly significant difference revealed that the PTSD group scored significantly lower than did the nonexposed group (p<0.0005; d=1.02) and nonsignificantly lower than did the no PTSD group (p<0.09; d=0.59). The no PTSD and nonexposed groups did not differ (p<0.42; d=0.44). The mean number of high-associate words recalled by the PTSD group corresponded to the 25th to 30th percentile of the no PTSD group and the 10th to 15th percentile of the nonexposed groups. In relation to the no PTSD group, 12.9% (N=4) of the PTSD group were frankly impaired; 35.5% (N=11) of the PTSD subjects were frankly impaired in relation to the nonexposed group.

There was no significant group difference in word stem completion (F=2.08, df=2, 77, p<0.14).The mean rates of target word stem completion were 45.0% (SD=14.4%) in the PTSD group (N=29), 46.1% (SD=12.7%) in the no PTSD group (N=16), and 51.7% (SD=13.8%) in the nonexposed group (N=35).

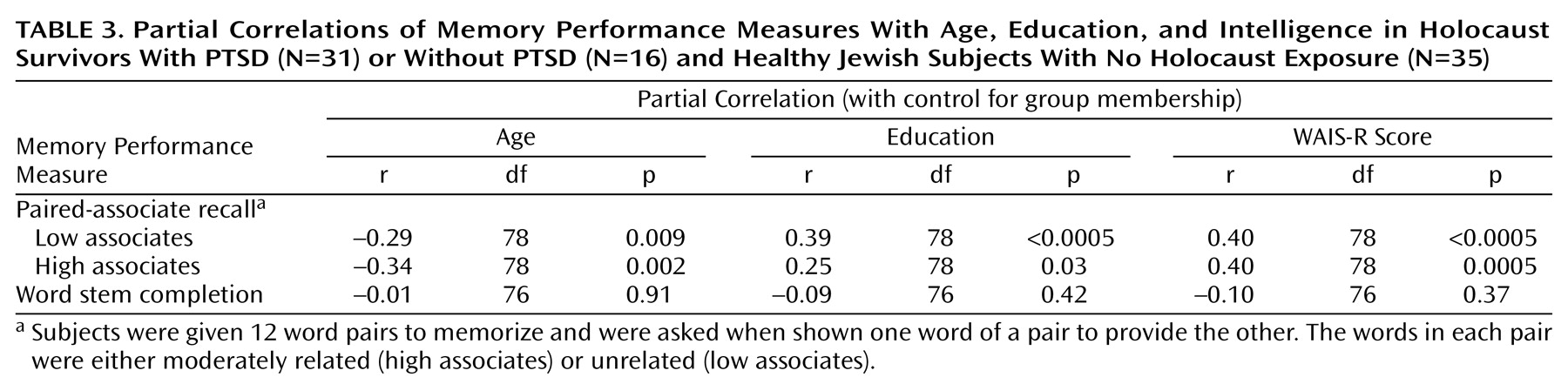

The correlations of memory performance with age, education, and intelligence are shown in

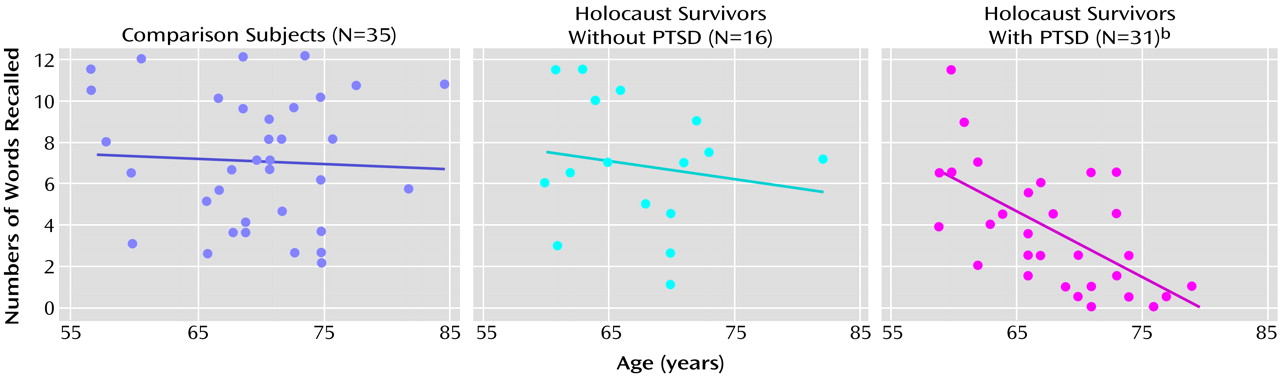

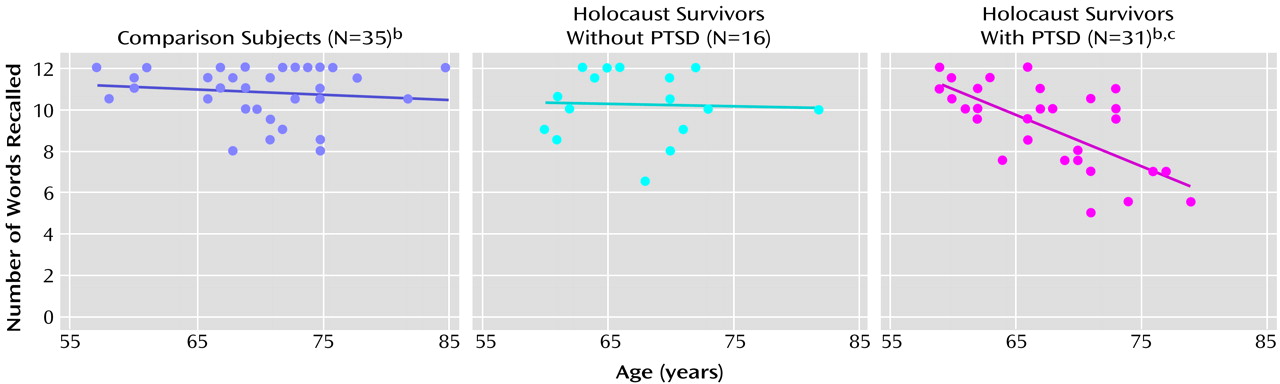

Table 3. There was a substantial inverse association of both low-associate and high-associate recall, but not word stem completion, with age. Similarly, paired-associate recall, but not word stem completion, was significantly associated with education and estimated intelligence. The correlations between age and paired-associate recall performance are shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. The association between age and low-associate recall was significant within the PTSD group but not within the no PTSD group (r=–0.19, df=14, p=0.490) or the nonexposed group (r=–0.09, df=33, p<0.62). The association in the PTSD group was significantly different from the nonexposed group (z=–2.56, p=0.01), and nonsignificantly differed from the no PTSD group (z=–1.68, p<0.10). The association between age and high-associate recall was substantial within the PTSD group but not within the no PTSD (r=–0.03, p<0.92) or the nonexposed group (r=–0.14, p=0.44). The association in the PTSD group was significantly different from both the nonexposed (z=–2.66, p=0.008) and no PTSD (z=–2.37, p<0.02) groups. The associations of IQ and education with paired-associate recall did not differ among the groups nor did the associations between age and word stem completion.

Discussion

Holocaust survivors with PTSD had poorer explicit memory than Holocaust survivors without PTSD or healthy Jewish subjects with no Holocaust exposure. The PTSD group scored significantly lower than both comparison groups on the more difficult low-associate recall condition. They performed less well than the nonexposed group on high-associate recall, which involves both semantic and explicit memory. On the basis of these measures, about one-third of the PTSD group performed at a level suggestive of frank cognitive impairment.

The finding of poorer explicit memory, but not implicit memory, in Holocaust survivors with PTSD is consistent with patterns described in lesions of the medial temporal lobe. Low-associate recall is an especially sensitive measure of hippocampal-dependent memory, requiring conscious effort and the formation of new semantic associations

(6,

24,

25). Thus, the findings suggest there may be reduced hippocampal-dependent memory function in Holocaust survivors with PTSD. This is consistent with the finding of smaller hippocampal volumes in other populations with chronic PTSD

(26–

29). However, as the PTSD group also had less education and scored lower on intelligence tests, the poorer memory performance could reflect a more general pattern of lower cognitive functioning.

The performance differences between the Holocaust survivors with PTSD and those without PTSD are particularly noteworthy, since the groups are similar in many ways. All subjects were exposed to massive psychological trauma during the Holocaust and profound loss and chronic stress in its aftermath. Additionally, as European immigrants, they had similar linguistic backgrounds. Although depression was prevalent among survivors, it did not account for the performance differences. Poor explicit memory has been found in major depression in other studies

(30,

31) but not in this one. This difference likely reflects that major depressive disorder occurred mainly as a comorbid disorder; as such, a diagnosis of depression may reflect symptom overlap or may be indicative of a secondary manifestation of PTSD rather than a primary affective disorder.

It is not known when these performance differences would have first been apparent. Since the PTSD survivors had fewer years of education and lower intelligence scores, it may be that differences would have been apparent before trauma exposure and that higher levels of education or better cognitive functioning were protective factors that helped some survivors recover from the trauma of the Holocaust. Indeed, there is evidence in other populations that less education or lower intelligence may be vulnerability factors that increase the risk of PTSD

(32,

33). It should be noted, however, that the PTSD group was of average intelligence and by no means uneducated; it is not known if differences within this range of intelligence and education are associated with differences in the risk for PTSD. In the literature on normal aging, for example, while lower education is a risk factor for age-related memory decline, education beyond 9 years does not appear to confer additional protection

(4).

Then again, some survivors were able to continue their education after the disruption of the Holocaust. Furthermore, current performance on the WAIS-R may be adversely affected by PTSD and may not reflect premorbid intelligence. Thus, lower educational attainment and performance on intelligence tests, as well as poorer explicit memory performance, may be sequelae of PTSD. The memory differences could have developed in tandem with PTSD or as a consequence of an interaction of chronic PTSD and aging. Aging is associated with hippocampal atrophy and poor explicit memory, and stress appears to accelerate memory decline

(4,

6,

7,

18). Thus, the differential association of recall and age in the present study raises the possibility that there is an interactive effect of age and PTSD on memory function in Holocaust survivors. These findings are consistent with the possibility of accelerated memory decline in Holocaust survivors with PTSD and with observations of premature aging in the Concentration Camp Syndrome

(1). However, such a possibility could only be conclusively demonstrated in a longitudinal study.

There are other possible explanations for the differential association between age and recall in this cross-sectional study. Survivors were all exposed to massive trauma during a discrete period in history. Their current age is highly correlated with age at exposure, making it difficult to disentangle these effects. Therefore, the findings could also reflect a differential effect of age at trauma exposure and PTSD on neurodevelopment. However, the literature on traumatic brain injury suggests the developing brain may be more susceptible to insults than the mature brain. For example, following traumatic brain injury, young children are more likely than older ones to have enduring neuropsychological deficits

(34,

35). Only when traumatic brain injuries occur in senescence is there a positive association between age and posttraumatic deficits

(36). Thus, if the effects of age at Holocaust trauma parallel those of physical trauma, they would not readily explain the age relationships found. Other trauma-related factors may have also influenced performance and its relationship with age. Physical trauma, disease, and malnutrition accompanied the psychological trauma of the Holocaust. Subjects with head trauma were excluded, but the remaining factors are difficult to quantify retrospectively and were too prevalent to serve as exclusionary factors but may have varied by age of exposure and diagnostic group and contributed to group differences.

English was not the native language for survivors, raising the question of whether linguistic differences explain the PTSD group’s poorer performance. Verbal tests are generally performed better in one’s native language, especially those that require speed (e.g., verbal fluency); however, the effects appear less pronounced on memory tests

(37–

39). For example, proficient Spanish-English bilinguals did not differ from monolinguals in recall or retention

(39). Subjects proficient in French and English had higher recall in both languages than monolinguals

(40). So it is unclear how differences in linguistic background might affect performance in these multilingual subjects proficient in English. Indeed, the pattern of differences found suggests such linguistic differences did not substantially account for the findings. Low-associate recall differed considerably between the Holocaust survivors with PTSD and those without PTSD, who have similar backgrounds. A similar magnitude of difference was seen between the PTSD and nonexposed groups, who have dissimilar linguistic backgrounds. Similarly, the no PTSD and nonexposed groups did not differ, suggesting the nonnative use of English did not appreciably affect performance.

The results are consistent with those studies which have found poorer memory performance in PTSD

(8–

11). The neuropsychological findings in PTSD have been inconsistent

(12–

14), even within rather homogeneous populations. The findings have been inconsistent in PTSD, even within rather homogenous populations. Studies comparing Vietnam veterans with PTSD to noncombat comparison subjects have found no differences in memory

(12), circumscribed differences in serial learning

(9), and diffuse impairments in verbal and visual memory

(8). Yet, when combat veterans with and without PTSD were compared, no differences were found in memory performance, including verbal paired associates

(13). A substantial proportion of PTSD subjects in the aforementioned studies had a history of substance abuse, also associated with memory deficits

(41), which may have contributed to the inconsistencies. Thus, the present study adds to this literature in finding poorer explicit memory in PTSD subjects than similarly exposed comparison subjects that could not be explained by depression or substance abuse.

If there is a different relationship between aging and cognitive functioning in PTSD, this might also explain some of the inconsistencies in the literature. There are no measures of memory that can be compared across existing studies of PTSD, but the Trail Making Test, an attentional measure sensitive to age, has been used in three studies of treatment-seeking Vietnam veterans with PTSD. The mean ages of the study groups were 37

(12), 43

(13), and 49

(42) years. With increasing age of the subjects studied, the PTSD-associated abnormalities became more apparent, and there was a corresponding increase in the mean time to complete part B (70, 83, and 101 seconds). This is consistent with the possibility that cognition is sensitive to age in PTSD even in domains that are not dependent on the hippocampus.

In summary, these findings demonstrate that there are considerable differences in explicit memory performance in Holocaust survivors with PTSD and that cognitive impairment may be an associated feature of this disorder in a subset of older survivors. Replication is needed in other populations, especially in those who sustained less severe psychological and physical trauma, in order to determine whether the findings are broadly applicable to PTSD. Longitudinal studies are also needed to clarify the significance of the apparent relationship between age and performance in PTSD. It has become increasingly clear that PTSD is a prevalent, chronic disorder associated with considerable functional impairment. Should PTSD be associated with accelerated cognitive decline, it would further increase the burden of this illness with aging.