Poor tenure, productivity, and satisfaction with work are major problems for most persons with schizophrenia. Historically, estimates of the rates of competitive employment among individuals with schizophrenia have been markedly low, ranging from 10% to 20%

(1). More recently, supported employment

(2) has been successful in helping over 50% of those with severe mental illness, and approximately 40% with schizophrenia, to obtain competitive employment, usually on a part-time basis

(3–

5). However, among those receiving supported employment services, only half maintain their jobs for more than 6 months

(6,

7).

The reasons for job termination among persons with severe mental illness include high levels of negative symptoms, poor social skills, interpersonal stressors, lack of family support, relapses consequent to medication noncompliance, dissatisfaction with work, and poor work quality

(8–

10). Interventions that can remedy some of these obstacles to sustained employment are available

(11–

13), but few treatment initiatives have aimed at facilitating the learning, mastery, and sustained performance of job tasks subsequent to employment. Improved techniques for teaching job tasks may be needed to take into account the neurocognitive deficits of schizophrenia that can impede the acquisition and performance of functional skills

(14,

15).

A number of different treatments have been recently proposed and tested for their efficacy at ameliorating neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia

(16–

23), most of which fall under the broader categories of restorative versus compensatory approaches

(24). Restorative efforts attempt to improve neurocognitive function by targeting the deficit directly through either pharmacological or psychosocial interventions. In contrast to restorative approaches, compensatory ones attempt to improve function by recruiting relatively intact neurocognitive processes to fill the role of impaired ones or by using prosthetic aids to compensate for the loss of function

(25).

In the present study, a compensatory training method, based on principles of errorless learning

(26,

27), was designed and tested for its efficacy at teaching persons with schizophrenia entry-level job tasks. Errorless learning minimizes the demands on explicit memory, which is impaired in schizophrenia

(28,

29), and instead relies more on implicit memory, which some but not all studies report to be relatively intact

(30–

33). This approach assumes that new learning is stronger and more durable if mistakes are eliminated during training. Performance becomes automated through imitative learning and repetitive practice of perfect task execution. Errorless learning has been used extensively in the clinical care and management of children with neurodevelopmental disabilities

(34–

36) and, more recently, in the rehabilitation of amnestic and schizophrenic patients

(37–

40).

Although healthy individuals can recruit neurocognitive resources needed to correct past mistakes and guide future behavior, many persons with schizophrenia cannot

(41,

42). By reducing the task to its basic components, each associated with a high likelihood for success, errorless learning minimizes failure during the acquisition of new skills and reduces the need for self-correction. This approach stands in marked contrast to the type of instruction typically provided to persons when they begin a new job. In such situations, new employees are commonly given verbal instruction, a demonstration, practice time, and then feedback about their performance. Training in this way generally leads to the commission of several mistakes that can be hard to correct because of difficulties in learning from past mistakes.

The present study aimed to test the hypothesis that errorless learning would be more effective than conventional trial-and-error training for teaching persons with schizophrenia entry-level job tasks as well as determine the extent to which the benefits of errorless learning lasted at a 3-month follow-up evaluation.

Method

Subjects

Sixty-five subjects who met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder from the Department of Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Healthcare Center and the San Fernando Mental Health Center participated in the study. Psychiatric diagnosis was determined after administration of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders Patient Edition (SCID-I/P)

(43) by an interviewer trained to use the SCID-I/P by the Diagnosis and Psychopathology Unit of the University of California, Los Angeles, Clinical Research Center for the Study of Schizophrenia. A minimum kappa of 0.75 for rating the presence of psychotic and mood items is required of all interviewers trained in the program. Subjects were clinically stable outpatients who had no psychiatric hospitalizations in the past 6 months, had been maintained on the same antipsychotic medication for the past 3 months, and had been unemployed for the past year. Antipsychotic medication type and dose were not controlled in the study but were left to the discretion of the subject’s treating physician. An abbreviated measure of overall work capacity

(44,

45) was used to screen potential participants who were good performers (i.e., greater than 90% accuracy) to reduce ceiling effects as well as provide a rough indication of baseline performance. Subjects also completed a neurocognitive assessment before training to explore whether errorless learning compensates for specific cognitive deficits. These data are available elsewhere

(46).

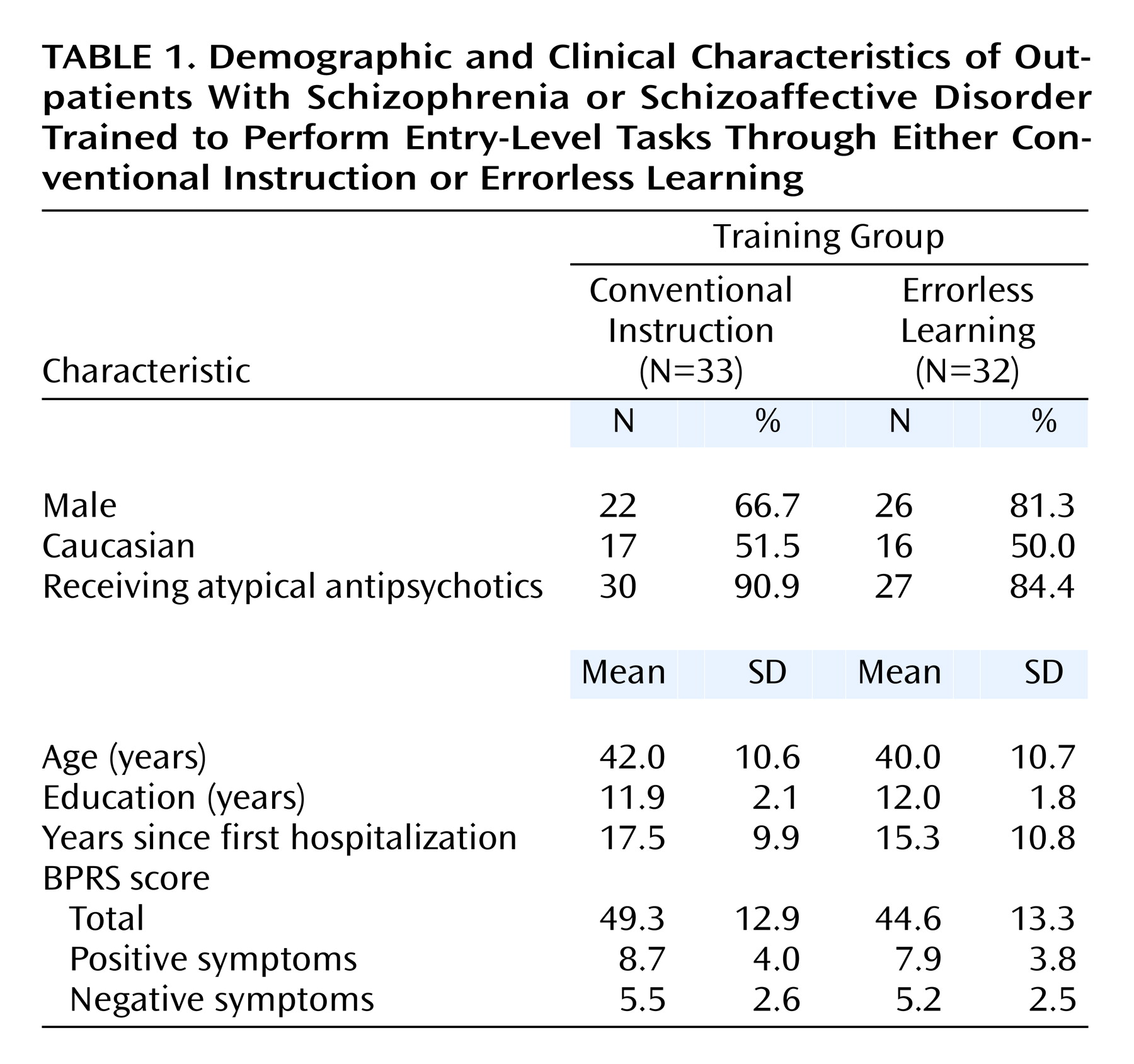

Table 1 presents the demographic, chronicity, and symptom characteristics for the study group, divided by method of training. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

Procedure

Following random assignment to training group (errorless learning or conventional instruction), all subjects received training on two entry-level job tasks: index card filing and toilet tank assembly. The tasks have standardized scoring procedures and good social and construct validity

(44,

45). The order of training on the job tasks was counterbalanced across groups. Training was conducted in small groups, usually with four subjects (range=2–4) in a simulated work environment with a supervisor and two assistants. Training was completed in a single session and lasted 45–60 minutes, depending on speed of skill acquisition. Separate workstations with dividers were set up so that subjects could not view the performance of others working on the same job task.

The groups were yoked for training time, in that the length of training for the errorless learning group dictated the length of training for the succeeding conventional instruction group. Training for the conventional instruction group included verbal instruction, a demonstration, time for independent practice, and supervisor feedback at the midpoint and end of the training session.

Training for the errorless learning group began with simpler task components and then proceeded stepwise to more difficult ones in which the task demands were progressively more complicated. At each stage, subjects met criteria for mastery by successfully completing a series of performance-based tasks without error. Training for the conventional instruction group involved more practice time and less didactic instruction compared with the errorless learning group. Training efficacy was assessed in separate 1-hour work sessions immediately after training particular to that job task and at a 3-month follow-up evaluation. Forty-eight of the 65 subjects were available for retest at the 3-month follow-up evaluation. Psychiatric symptoms were assessed within a 2-week window of training by using the 24-item Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)

(47) and were administered by an interviewer trained to a minimum intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.80 by the Diagnosis and Psychopathology Unit.

Index Card Filing

This task involved filing 40-card piles of index cards. Subjects were told that each card contained information about a person who had purchased a car. Each card contained the city of purchase, car manufacturer, and owner’s last name printed in large (20-point) boldface type (Arial font). Subjects filed the cards into filing boxes according to city of purchase, car manufacturer, the alphabetical section for the owner’s last name (e.g., A-F, G-L), and alphabetical order according to the owner’s last name. Dependent variables included measures of accuracy ([total number of cards filed correctly/total number of cards filed] × 100), speed (total number of cards filed per unit time), and overall productivity (total number of cards filed correctly minus total number of cards misfiled).

Toilet Tank Assembly

This task involved assembling the kind of toilet tank commonly found in community home refurbishing stores. The 31-piece assembly kit included a flush valve, fill valve, and lever arm assemblies. Subjects were instructed to complete assembly of the entire kit. Analogous to card filing, the dependent variables for tank assembly included measures of accuracy ([total number of parts correctly assembled/total number of parts completed] × 100), speed (total number of tanks completed per unit time), and overall productivity (total number of parts assembled correctly minus total number of parts missing or incorrectly assembled).

On-Task Performance

Assessment of on-task behavior followed established time-sampling procedures

(48) in which a timer signaled raters to conduct a 2-second observational sweep of subjects at 5-minute intervals throughout the duration of the two posttraining work sessions (immediately after training and at the 3-month follow-up evaluation). On-task performance was defined as the execution of a behavior required to complete the task (e.g., picking up an index card, looking on the table for a tank assembly piece). Examples of off-task behaviors included staring out the window or talking to another subject. On-task performance was scored as a dichotomous variable (0=off-task; 1=on-task). Assessment of interrater reliability yielded a kappa of 0.89.

Subject Satisfaction With Training

A 10-point Likert scale was administered to a subset of subjects (N=36) to measure the potential adverse effects of trainer bias and subject satisfaction with training (1=extremely negative, 10=extremely positive). Separate ratings were obtained for each job task.

Data Analyses

Initially, contrasts were conducted on demographic, chronicity, and symptom measures to examine possible group differences at the time of training. Correlational analyses were performed to examine possible significant relationships between symptoms and job task performance for the two training groups. The three dependent measures from each job task were then analyzed separately by using a group (errorless learning versus conventional instruction) by time (immediate versus 3-month follow-up) 2×2 repeated-measures analysis of covariance with baseline performance on the screening measure of work capacity entered as the lone covariate. Because of the skewed score distributions for accuracy on both job tasks, these data were log transformed. The card filing data were normalized after transformation and were analyzed by using the SAS mixed model procedure

(49). The data from the tank assembly task could not be normalized and were thus analyzed by using the SAS general model procedure for Poisson distributions. Follow-up between- and within-group contrasts were conducted on all significant main (i.e., group, time) and interaction (i.e., group-by-time) effects. Between-group contrasts were also conducted on measures of on-task performance and subject satisfaction with training.

Results

There were no differences between the two groups on any demographic or chronicity measures, and the two groups were also comparable in their severity of symptoms at the time of training (

Table 1). No significant correlations were found between symptoms (BPRS total, positive symptom, and negative symptom scores) and job task performance (accuracy, speed, and productivity) for either training group (conventional instruction: all p>0.18; errorless learning: all p>0.15).

Efficacy

Accuracy

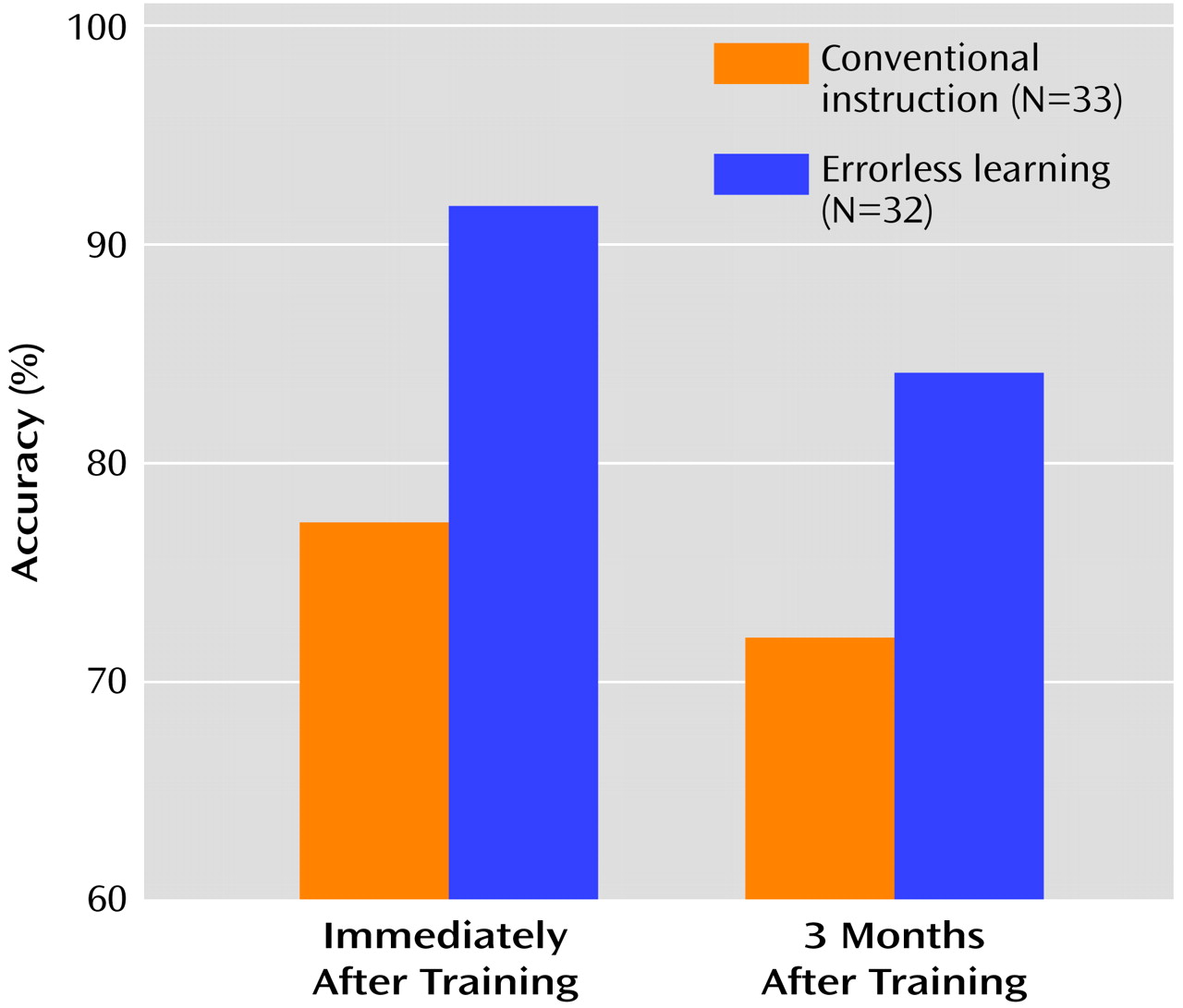

For card filing, the results revealed a significant effect of group (F=4.92, df=1, 59, p=0.03), a nonsignificant effect of time (F=2.84, df=1, 44, p<0.10), and no interaction effects. That is, the errorless learning group showed better overall performance than the conventional instruction group, and performance in both groups declined over the 3-month follow-up period at about the same rate (

Figure 1). Similar results were found for toilet tank assembly, for which there was a significant effect of group (χ

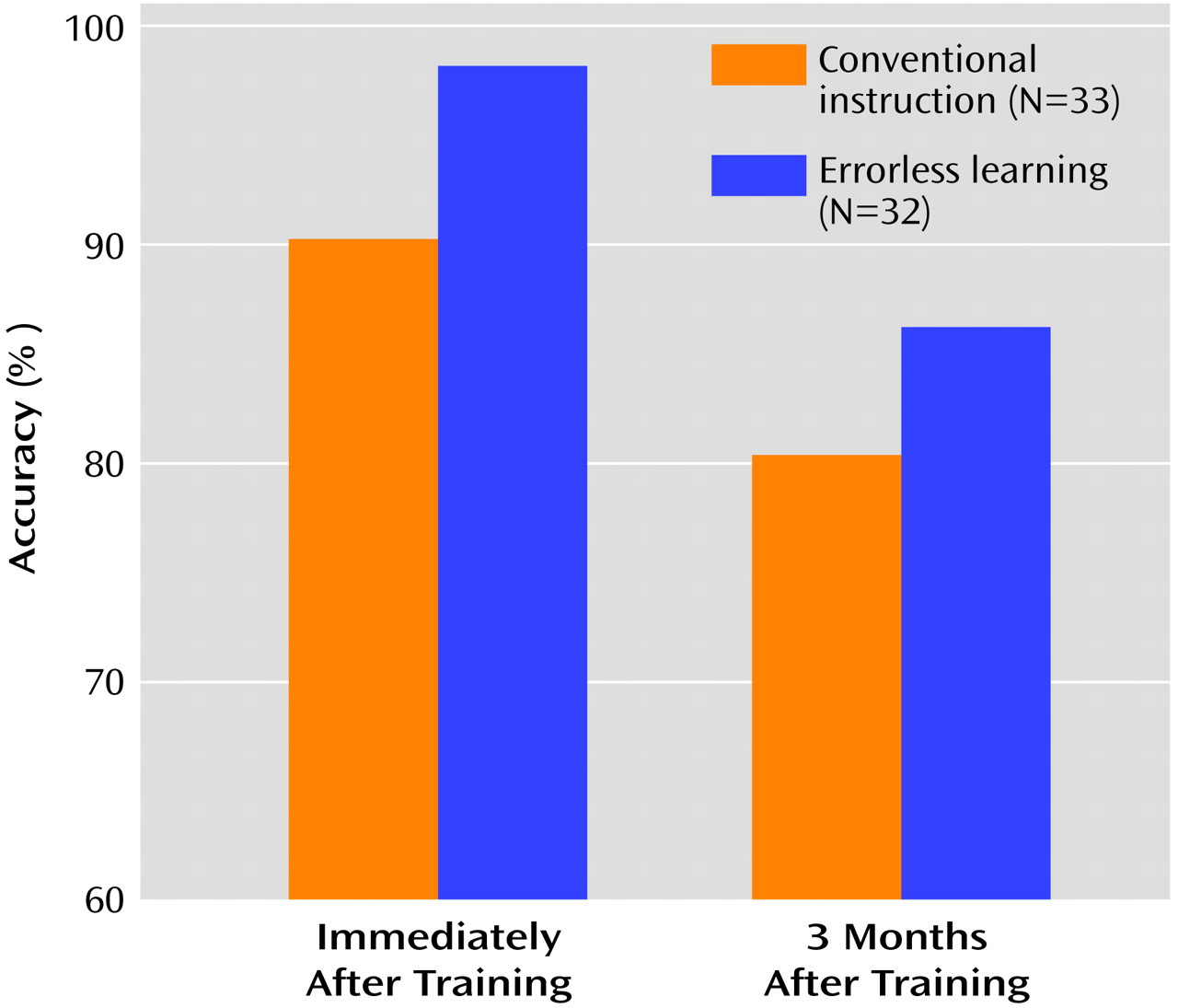

2=4.39, df=1, p<0.04) and time (χ

2=34.42, df=1, p<0.0001) but no group-by-time interaction. The errorless learning group showed better overall performance, but the performance of both groups declined significantly over the 3-month follow-up period (

Figure 2).

Speed

For the card filing and tank assembly tasks, the results failed to reveal any significant group, time, or interaction effects (all p>0.15).

Productivity

For card filing, there was a significant effect of group (F=7.18, df=1, 59, p<0.01) but no significant time or interaction effects. The errorless learning group showed better overall productivity than the conventional instruction group, and the level of productivity of the groups was relatively stable over time. For tank assembly, there was a nonsignificant training effect differential that favored the errorless learning group (F=3.30, df=1, 60, p<0.08), and there was a significant effect of time (F=8.64, df=1, 44, p<0.006), but there was no group-by-time interaction. The overall performance of the errorless learning group tended to be better than the conventional instruction group, but both groups showed a decline in productivity over time.

On-Task Performance

The two groups were highly comparable in their on-task performance during the assessment periods conducted immediately after training (card filing: t=0.379, df=61, p=0.71; tank assembly: t=–1.105, df=62, p=0.27). The percentage of time on task was quite high during card filing (conventional instruction: mean=99.1% [SD=3.5%]; errorless learning: mean=99.1% [SD=2.9%]) and tank assembly (conventional instruction: mean=98.6% [SD=6.5%]; errorless learning: mean=99.1% [SD=3.6%]). Similar results were obtained for the measurements obtained at the 3-month follow-up evaluation.

Subject Satisfaction With Training

The results revealed the two groups to be highly comparable in their ratings of the training procedures for both job tasks (card filing: t=0.29, df=34, p=0.78; tank assembly: t=–0.07, df=34, p=0.95). In addition, the ratings were high for both groups across job tasks, indicating that the vast majority of subjects, regardless of training group, favorably experienced the training procedures for card filing (conventional instruction: mean=8.84 [SD=1.54]; errorless learning: mean=8.71 [SD=1.26]) and tank assembly (conventional instruction: mean=8.79 [SD=1.62]; errorless learning: mean=8.82 [SD=1.38]).

Discussion

The present study examined the efficacy of errorless learning at teaching two entry-level job tasks to a group of unemployed, clinically stable outpatients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. The results showed that errorless learning was better than conventional instruction at improving accuracy but had little effect on speed. Of note, the level of accuracy on the card filing task after errorless training was roughly comparable to the level attained by a group of healthy comparison subjects who took part in an earlier project that used this same measure

(45) (healthy subjects: mean=95.0%, SD=8.1%; patients: mean=91.8%, SD=11.4%). On a measure of productivity that took into consideration speed and accuracy, the errorless learning group performed better than the conventional instruction group on the card filing task, and there was a trend in the same direction for the tank assembly task.

Why might errorless learning be an effective training intervention for persons with schizophrenia? It has been suggested that among the neurocognitive deficits associated with schizophrenia, the disturbances to explicit memory and related systems are disproportionately large

(28,

29). In contrast, some, but not all, studies report implicit or procedural-based learning to be relatively intact

(30–

33). It stands to reason that a training intervention that minimizes the demands on impaired neurocognitive processes and instead emphasizes the recruitment of more intact ones might be a better training intervention with this population. From a more experiential perspective, one advantage of errorless learning is that subjects are largely insulated from the experience of failure and the potentially negative cascading effect this experience may have on skill acquisition.

Regardless of its theoretical underpinnings, the efficacy of errorless learning as examined in the present study should be interpreted vis-à-vis certain potentially key influences on performance outcome. Observed effects could be due to differences in the amount of time spent in training-related activities, trainer bias, on-task behavior, or baseline characteristics. As part of the study design, total time engaged in training-related activities was equated for the two groups. However, the amount of time devoted to certain aspects of training (e.g., instruction, practice) differed. For the errorless learning group, more time was allocated to trainer-provided instruction, whereas for the conventional instruction group more time was allocated to independent practice. Hence, the possibility that efficacy may be related to the amount of trainer-provided instruction cannot be ruled out. With respect to trainer bias, measured by participants’ satisfaction with the training, the results indicated that both groups perceived training quite favorably. Similarly, there were no group differences in on-task performance, and the overall level was quite high. Finally, the differential training effects do not appear to be due to differences in demographic, chronicity, or symptom characteristics, since the groups were roughly comparable on these variables, and symptoms also showed no significant relationship to job task performance.

When we examined the extent to which training effects were maintained over time, the results showed that performance accuracy dropped for both groups over time. Subject attrition and increased score variance may have contributed to the failure to detect differential maintenance of training effects. Consideration should also be given to the fact that subjects had no subsequent exposure to the job tasks from the time of training to the 3-month follow-up evaluation. This arrangement bears little relationship to the realities of the workplace, in which newly hired personnel are given ample opportunity to practice and consolidate their job skills. In addition, supported employment programs provide job coaches to be available indefinitely to reinforce job performance once tasks are learned. Thus, the experiment was an unusually stringent test of the durability of either training method.

The hypothesis that the errorless learning group would show a differential training effect on speed of performance was not supported. The training procedures for the present study were not designed to improve speed per se but rather accuracy. The prediction regarding speed was primarily based on observation of subject performance from an earlier study aimed at remediating performance deficits on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test

(50) in which subjects’ sorting of cards appeared to be automated after training, hence requiring little cognitive effort in the decision-making process.

On the basis of these findings, and those from other studies

(20,

37–40,

51,

52), there appears to be ample support for continued testing of errorless learning for use in work rehabilitation. Errorless learning can be applied to a wide variety of job tasks, particularly those typically provided to seriously mentally ill clients at entry-level positions

(53). Future efforts may aim to test the effectiveness of errorless learning at actual work sites in the community with the teachers being job coaches. There are practical limitations to errorless learning. Obviously, the more diverse and multifaceted the job, the more difficult and time-consuming it would be to apply errorless learning training procedures. Even with relatively simple job tasks, errorless learning takes considerably longer than conventional methods of instruction. Studies examining the cost/benefit ratio of errorless learning are warranted.