Despite the availability of effective regimens of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy

(1,

2), only a small fraction of patients with common mental disorders are adequately treated in a year

(3,

4). Recent research has begun to shed light on some components of this problem, such as the failure of mentally ill people to recognize that they have clinically significant emotional problems

(5,

6), their failure to seek treatment once the need is recognized

(5,

7), and the failure of the treatment system to provide adequate treatment

(8–

10). However, less is understood about the extent to which patients fail to adhere to a full course of treatment. Prior studies of treatment dropout have often been limited by small and highly restricted study groups, such as patients with a single mental disorder or patients from a single treatment setting

(11–

28). Perhaps because of such limitations, these studies have produced inconsistent findings regarding both the frequency and predictors of treatment dropout.

Identifying the extent and reasons for treatment dropout is a critical task for several reasons. Most important, mental health treatments that are delivered for inadequate durations are ineffective

(29,

30). In addition, dropping out of mental health treatment is very common

(22,

23), perhaps because some patients with mental disorders possess few resources to pay for treatments, are impulsive or disorganized, are pessimistic regarding treatment effectiveness, or are sensitive to treatment side effects

(31–

34). Information on the prevalence and determinants of treatment dropout is essential for designing and targeting interventions and health care policies to increase the proportion of patients who complete adequate courses of care.

The first aim of the present study was to present representative data on the prevalence of mental health treatment dropout across the full range of specialty, general medical, and human services settings in both the United States and Ontario. The second aim was to evaluate the effects of four classes of dropout predictors: clinical conditions, treatment modalities, negative attitudes toward mental health treatments, and demographic features. These predictors were selected on the basis of earlier research, which has suggested that treatment dropout varies by type of mental disorder

(14,

25) and that high rates of treatment dropout are associated with not receiving a combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy

(16,

21,

28,

35); believing that mental health treatments are ineffective or intolerable

(12,

16,

21,

23,

25); and demographic features such as young age

(12,

13,

15,

24), low income

(23,

26,

27), low education

(12,

23,

25), and being male

(13,

21,

25,

27). In addition, since all residents of Ontario had access to free mental health treatment with no cap on the number of covered visits at the time of the survey, it was possible to assess indirectly the effect of these potential financial factors on dropout by comparing results in Ontario with those in the United States

(5–

7,

21,

26,

27).

Method

Study Population

Data for this study came from the United States National Comorbidity Survey

(36) and the Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey

(37). Both surveys were carried out by using face-to-face interviews in probability samples of the general household population. The content of the interviews was described to potential respondents, and verbal informed consent was obtained before beginning the interviews. In the case of minors (age range=15–17 years), who were included in the National Comorbidity Survey, parental verbal consent also was obtained before seeking verbal consent from the potential respondents. The National Comorbidity Survey was administered in 1990–1992 to 8,098 respondents, with a response rate of 82.4%. Questions regarding the use of services were then administered to a probability subsample of 5,877 respondents. The Mental Health Supplement was administered in 1990 to a follow-up sample of 9,953 random respondents selected from the households that participated in a one-quarter replicate of the Ontario Health Survey. The Ontario Health Survey response rate in the Mental Health Supplement replicate was 88.1% and, in these households, 76.5% participated in the Mental Health Supplement, for an overall response rate of 67.4%. In the current report, we focus on the 830 National Comorbidity Survey respondents and 431 Mental Health Supplement respondents in the age range 15–54 who received treatment for self-defined problems with “emotions, nerves, mental health, or use of alcohol or drugs” at some time during the 12 months preceding their interview.

Measures

Respondents who reported that they had received mental health treatment at some time during the 12 months preceding the survey were asked if they were still in treatment at the time of interview. Those who reported that they were not currently in treatment were then presented with a list of reasons for termination and asked to endorse all those that applied. Treatment dropouts were defined as those no longer in treatment who did not report that symptom improvement was a reason for their termination.

Potential predictors of treatment dropout were defined by using the following patient sociodemographic features: age (divided into four categories: 15–24, 25–34, 35–44, and 45–54 years); gender; family income, defined in U.S. dollars for both surveys and then trichotomized in the two surveys combined into three groups of roughly equal size; urbanicity, dichotomized in both Ontario and the United States as counties that had a population of 50,000 or more (urban) versus under 50,000 (rural); country of residence; and education, dichotomized into those with at least some college education (high education) versus no college (low education). In the United States, race/ethnicity was categorized as non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and others (mainly non-Hispanic white). Information on race/ethnicity was not available in Ontario. In the United States, insurance status was dichotomized into those with coverage for outpatient treatment of psychiatric problems versus those without such coverage. Insurance coverage was not assessed in Ontario because all residents of Ontario had access to free mental health treatment at the time of the interview.

The presence of DSM-III-R mental disorders in the year preceding the interview was assessed with a modified version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview

(38), a fully structured diagnostic interview designed for use by trained interviewers who are not clinicians. Ten disorders occurring in the year preceding the interview were assessed: major depressive episode, mania, dysthymia, social phobia, simple phobia, agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, alcohol abuse or dependence, and drug abuse or dependence.

Patients’ attitudes about mental health treatment were defined on the basis of their responses to two questions. The first was a question concerning how comfortable respondents would be seeing a mental health professional (categorized as very, somewhat, not very, and not at all comfortable). The second question asked respondents to estimate the percentage of patients who were helped by mental health treatments. Respondents were then dichotomized into those who felt treatments were efficacious (i.e., felt that ≥50% of patients were helped) or were not efficacious (i.e., felt that <50% of patients were helped).

Characteristics of providers seen in the year preceding the interview were also defined, such as the types of providers seen as well as the number of visits made to each type of provider. The types of providers were categorized on the basis of treatment modalities that each could have provided to patients: pharmacotherapy (psychiatrists and nonpsychiatric physicians); talk therapy (psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and mental health counselors); and spiritual counseling (priests, rabbis, and ministers). Finally, visits to these three provider types were then used to define patients who may have received 1) pharmacotherapy and talk therapy (dual modality), 2) talk therapy but no pharmacotherapy, 3) pharmacotherapy but no talk therapy, and 4) spiritual counseling only.

Analysis

Patient reports of the number of visits to all providers combined in the past year were first used to construct a data file that included a separate record for each person-visit. The influence of heavy service users was minimized by excluding all visits subsequent to the 25th visit. This yielded a total sample of 9,921 person-visits among 1,261 patients. Patterns of dropout were then examined by using Kaplan-Meier

(39) curves, where dropout was defined as terminating treatment with at least one type of provider for reasons that did not include symptom improvement. Predictors of dropout were examined by using discrete-time survival analysis

(40) in the pooled person-visit data array. Patients who terminated treatment because of symptom improvement were censored at the time of termination, while patients who dropped out of treatment after 25 visits were coded as stably in treatment for the range of visits examined here.

On the basis of a review of the existing literature

(11–

28), we hypothesized that dropout would be affected by four classes of predictors: sociodemographic characteristics, type of disorder, treatment type, and negative attitudes toward mental health treatment. We used likelihood ratio chi-square analyses to test whether each class of predictors significantly predicted dropout in multivariable models. Coefficients for individual predictors were interpreted only if the omnibus test for that class of predictors was statistically significant. In addition to main effects, we evaluated differences in the effects of each class of predictors between the United States and Ontario in an effort to detect effects that might be significant in only one of the two samples.

Results

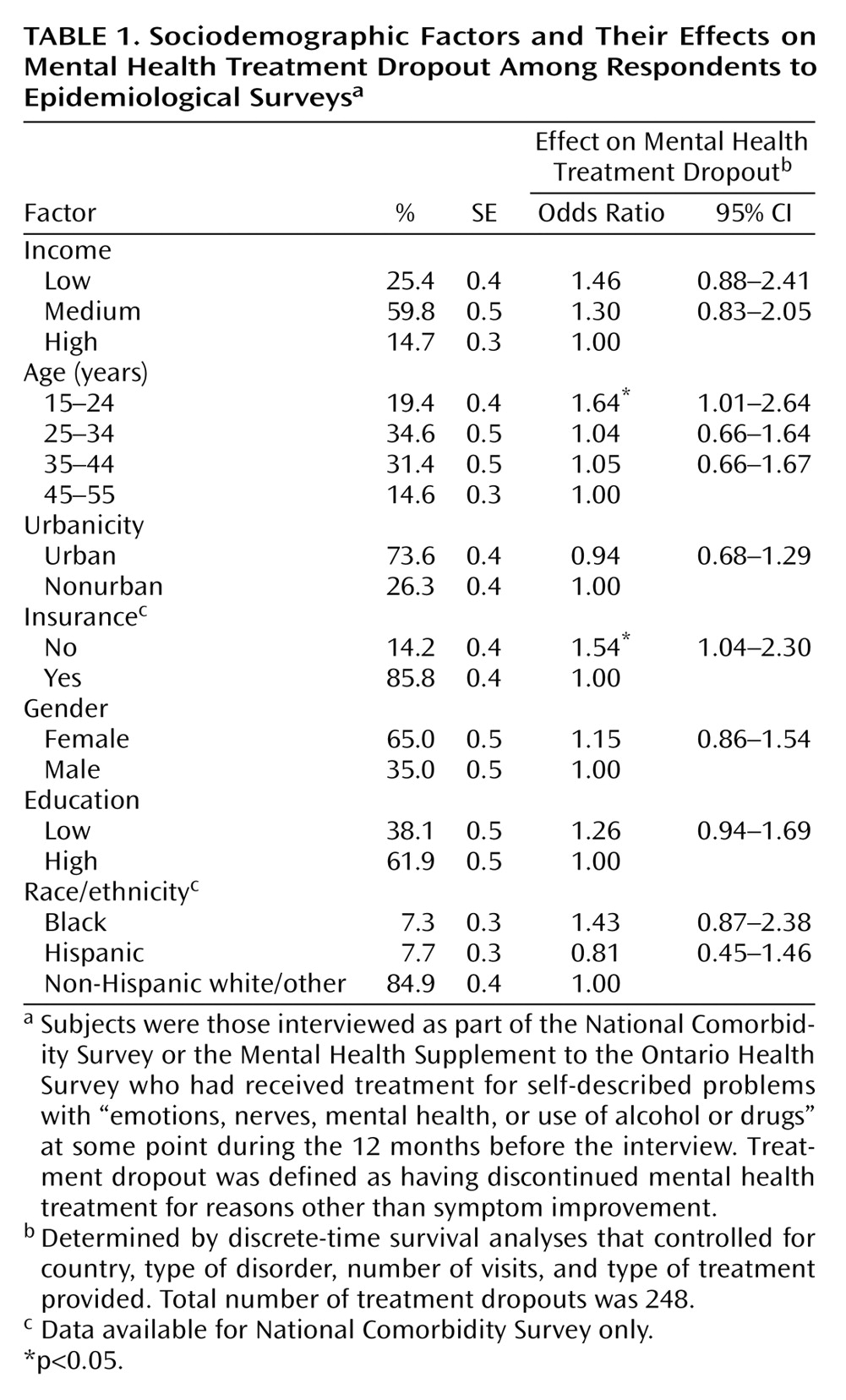

Kaplan-Meier curves (

Figure 1) show that there was no difference between the United States and Ontario in the cumulative probability of treatment dropout (χ

2=1.2, df=1, p<0.28). Approximately 10% of patients in both the United States and Ontario dropped out by the fifth visit, 18% by the 10th visit, and 20% by the 25th visit. The crude dropout rates of 19.2% in the United States and 16.9% in Ontario are somewhat lower than the estimated cumulative probabilities by the 25th visit because not all respondents had completed 25 visits as of the time of interview.

No significant effect of diagnosis on dropout was found in an additive model that used the 10 DSM-III-R diagnoses as predictors in the total sample and controlled for country and number of visits (χ2=13.1, df=10, p<0.22; results not shown). There was also no significant difference between the United States and Ontario in the effect of diagnosis in predicting dropout (χ2=9.8, df=10, p<0.46).

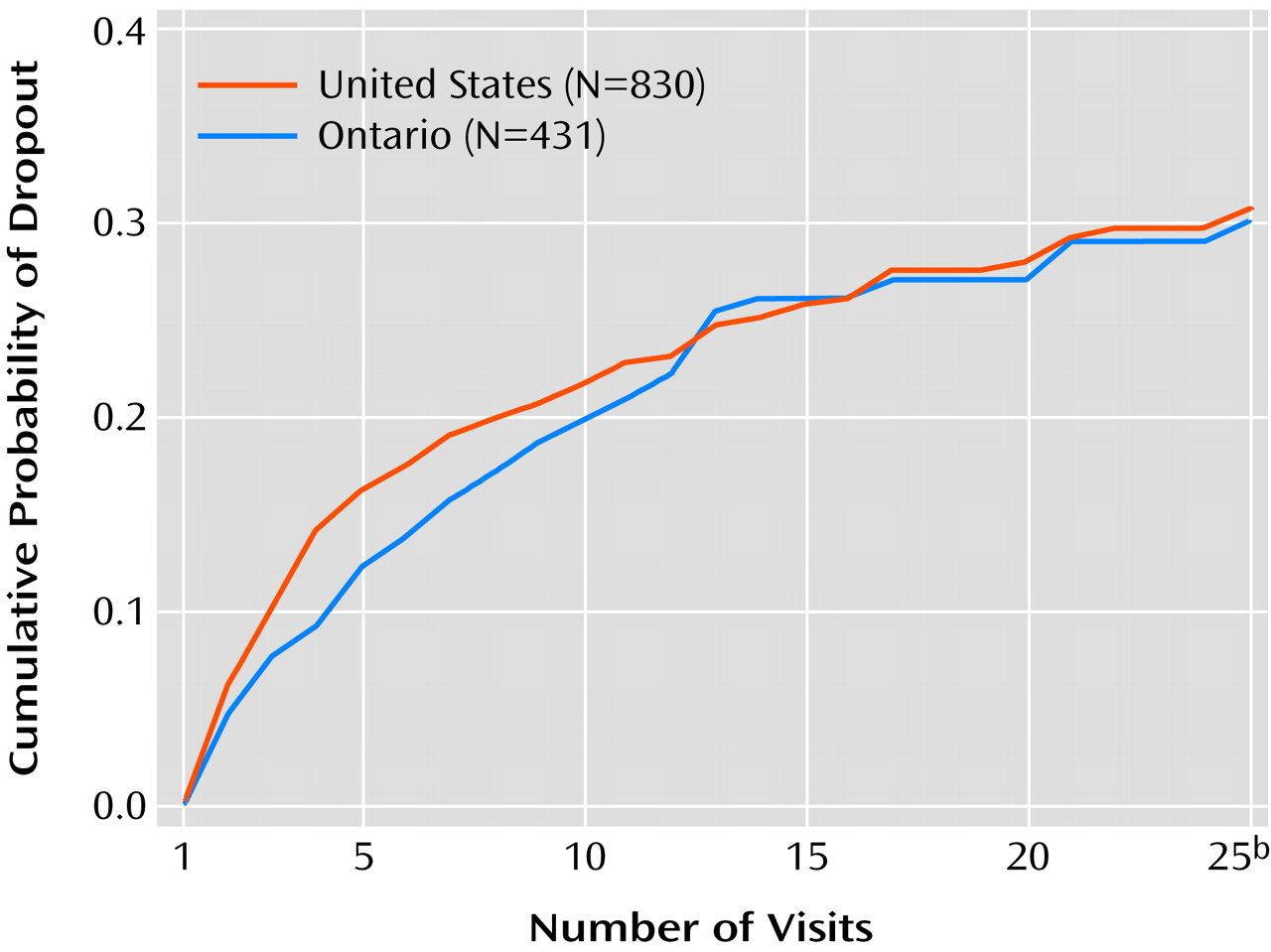

The difference in dropout across provider types was statistically significant in an omnibus test of the total sample that controlled for country, type of disorder, and number of visits (χ

2=9.6, df=4, p<0.05). Kaplan-Meier curves for each provider type (

Figure 2) show that dropout was significantly higher among patients exclusively in treatment with a spiritual advisor than among those seeing a nonpsychiatric physician (p<0.051) or any other provider type (p<0.001). Dropout was significantly lower among those seen in a setting that could provide dual-modality treatment relative to treatment of any other type (p<0.001). Dual-modality treatment can be provided either by a psychiatrist or by a combination of a nonpsychiatric physician and a nonphysician mental health professional. No statistically significant difference was found between the dropout rates of patients receiving these two types of dual-modality treatment (χ

2=0.1, df=2, p<0.76). No significant difference between the United States and Ontario was found in the effect of provider type (χ

2=3.0, df=3, p<0.38).

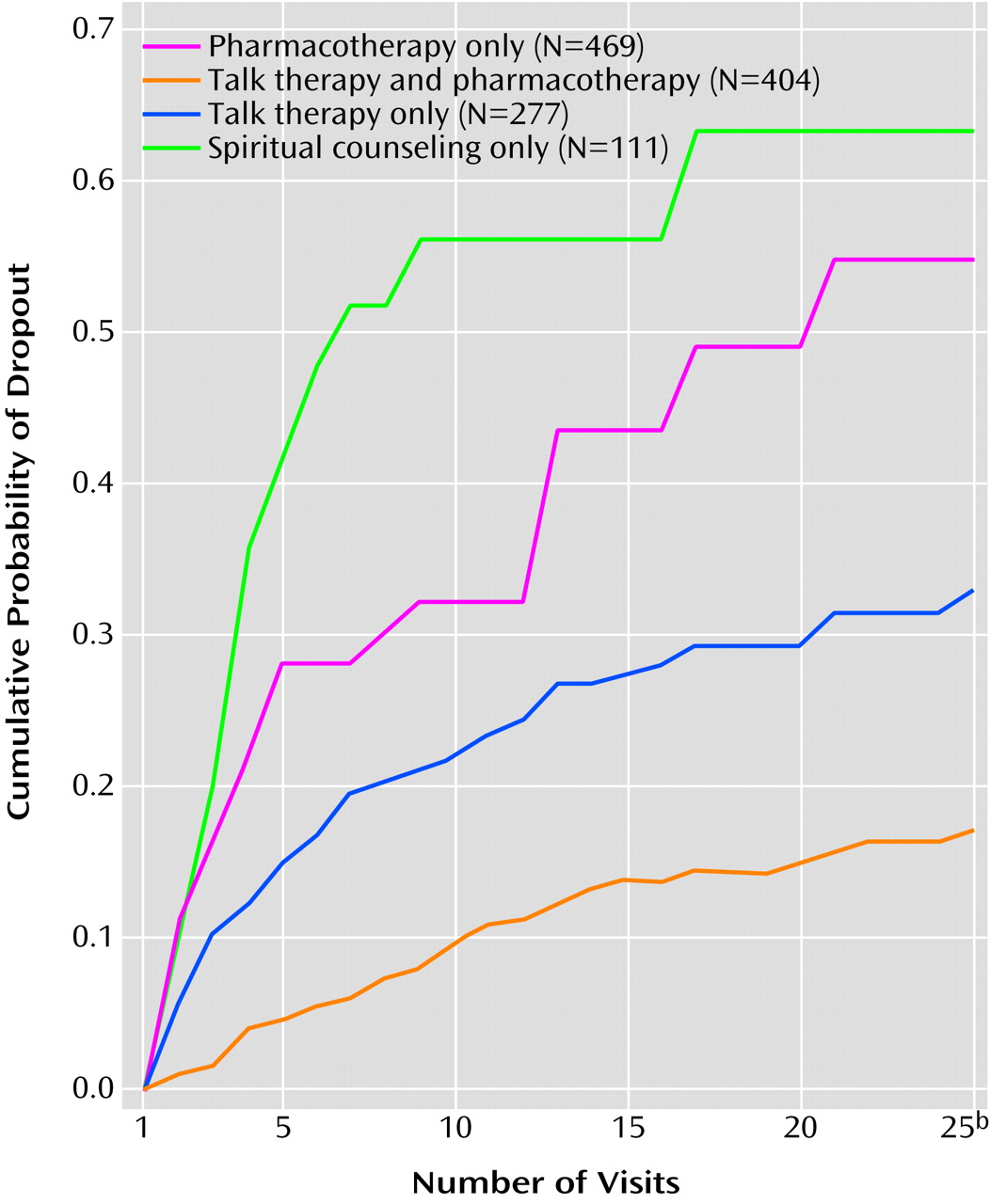

The distribution of sociodemographic characteristics in the total sample is shown in

Table 1. The effects of sociodemographic variables on dropout were significant in an omnibus test (χ

2=23.7, df=11, p<0.02) in the total sample, controlling for country, type of disorder, number of visits, and provider profiles. As shown in the last two columns of

Table 1, age and insurance were the only individually significant predictors, with the highest dropout rates among the young and those without insurance. The effects of income, urbanicity, gender, education, and race were not found to be significant. No significant difference between the United States and Ontario was found in the overall effects of sociodemographic characteristics (χ

2=15.2, df=11, p<0.18).

The independent effects of patients’ attitudes about mental health care on treatment dropout were examined in models that controlled for country, diagnosis, provider profiles, number of visits, and sociodemographic variables (results not shown). The effects of the two attitude measures (one coded as a set of three dummy variables and the other as a single dummy variable) were significant in an omnibus test (χ2=33.2, df=4, p<0.001). Compared with the odds of dropout among respondents who reported being very comfortable seeing a mental health professional, the relative odds of dropout were 2.4 (95% CI=1.4–4.1) among respondents who reported being very uncomfortable, 2.7 (95% CI=1.7–4.2) among those who reported being somewhat uncomfortable, and 1.6 (95% CI=1.1–2.2) among those who reported being somewhat comfortable. Respondents who perceived the efficacy of mental health treatment to be low had relative odds of dropout of 1.6 (95% CI=1.2–2.2) compared with those who perceived efficacy to be high. The effects of attitudes on dropout did not vary significantly by country (χ2=2.7, df=4, p=0.66).

Discussion

These results should be interpreted with the following four sets of limitations in mind. First, we used retrospective self-reports to assess whether respondents had psychiatric disorders and stayed in treatment for those disorders, introducing the possibility of recall bias. Although we focused on disorders and treatments in the most recent year to minimize this problem, recall bias might nonetheless have affected results. In addition, we only considered whether patients dropped out of treatment and did not consider the degree to which patients were adherent to their treatment before dropping out. This focus was based on suggestions from previous research that self-reports of dropout are more accurate than self-reports of the degree of adherence

(41–

43). Furthermore, we failed to consider whether the treatments given to patients before they dropped out were appropriate nor did we evaluate whether treatment dropout was associated with worse clinical outcomes. In addition, we used visits to practitioners qualified to provide types of treatments as a proxy for the types of treatments received (i.e., pharmacotherapy and talk therapy), with the likely consequence that we misclassified the type of treatment received for some respondents.

Second, we examined the influence of a limited number of patient and provider characteristics on dropout. We did not have the ability to investigate other important factors, such as those related to treatment regimens and health care systems, because information about these factors was not collected in the surveys. Furthermore, because of the fact that the surveys were cross sectional, it is not clear whether some of the significant “predictors” (e.g., attitudes towards treatment) actually occurred before dropout. In addition, it is unclear to what extent the results regarding the effects of these predictors can be generalized to other populations of interest.

Third, although omnibus tests were used to evaluate the significance of the predictors in an effort to reduce the probability of false positive results, the fact that we included a large number of predictors raises the possibility that at least some of the statistically significant predictors were due to chance. This concern is reduced somewhat, however, by the fact that all the predictors judged to be statistically significant have all been found in previous studies.

Finally, there have been dramatic changes in mental health treatments (e.g., introduction of new medications with potentially greater tolerability) and delivery systems (e.g., greater proportions receiving mental health treatment under managed care) since data collection for the National Comorbidity Survey and Mental Health Supplement were completed in the early 1990s. The impact of these changes on treatment dropout is unknown, although emerging evidence from the latter half of the 1990s indicates that it is still the case that a substantial proportion of patients in treatment for mental disorders fail to complete a full course of treatment

(8). The National Comorbidity Survey Replication, which is currently in progress in the United States, will provide data on temporal changes in treatment dropout over the past decade that will resolve this uncertainty

(44). Until these results are available, however, it will remain unclear whether the patterns reported in this article still hold.

In spite of these limitations, this study sheds new light on the magnitude of the problem of mental health treatment dropout. The crude dropout rates of 19% in the United States and 17% in Ontario are comparable to the dropout rate of 17% recently observed in a study of mental health advocacy group members in 11 countries

(21). However, most earlier studies reported much higher rates of treatment dropout than these

(22,

23). There may be two reasons for this discrepancy. First, we employed a more conservative definition of dropout than previous studies in that we did not consider respondents who reported improvement as having dropped out. Second, most prior studies were carried out within a single treatment setting and may have misclassified patients who switched to providers in another setting as dropouts, leading to an overestimation of the actual dropout rate

(11). Our analysis, in comparison, was based on patient reports of their treatment across all treatment settings, allowing us to correctly identify patients who switched providers as still being in treatment.

The sociodemographic analysis found that young adults were significantly more likely than older adults to drop out of treatment in both the United States and Ontario. This has been observed before and explained in part by the fact that the young often must depend on others around them to receive treatment (12, 13, 15, 24). A greater likelihood of the young dropping out of treatment may underlie the greater morbidity, dysfunction, and worse longitudinal course that have been observed among patients who have onsets of mental illness early in life

(45,

46).

Lack of insurance coverage was found in this study, as well as in previous research

(21), to be significantly related to dropout. This result has particular relevance in the United States, where there is currently a debate over whether to expand the mental health benefits covered by insurance. Results of this study suggest that a sufficient breadth and intensity of mental health treatments must be covered by insurance or patients will drop out and not receive adequate courses of treatment.

Dropout was also found to vary depending on the type of mental health care received, with patients receiving dual-modality treatments substantially more likely than others to remain in treatment. Previous naturalistic research has been consistent with this finding in showing that a combination of pharmacotherapy and talk therapy enhances treatment compliance compared with single modalities

(16,

21,

28,

35). Consistent with these naturalistic findings, recent clinical trials have shown that patients randomly assigned to receive both psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in integrated treatment models are significantly more likely to complete a full course of treatment and experience improved clinical outcomes

(47–

49). It is of interest that we observed in post hoc analyses that the positive effect of dual-modality treatments on reduction in dropout was not affected by whether this treatment was provided by a psychiatrist or by a combination of a nonpsychiatric physician and a nonphysician mental health professional (i.e., a social worker, counselor, or psychologist). This is an important finding in light of the increasing use of collaborative treatment featuring pharmacotherapy provided by a primary care doctor and talk therapy provided by a nonphysician mental health professional.

Results of our analyses of patients’ attitudes about mental health care should raise at least two concerns. First, a large proportion of respondents believed that mental health treatments are not effective. Patients who held such a belief were significantly more likely to drop out of treatment. These findings suggest that clinicians should spend additional time and effort to educate their patients concerning the effectiveness of mental health treatments. In our recent study of mental health advocacy group members, we observed that receiving such education from providers was critically important in facilitating patients’ acceptance of their treatments

(21). Second, respondents who reported feeling uncomfortable in mental health care were substantially more likely to drop out than patients who reported being comfortable. A likely explanation for this finding is that expressing greater discomfort with mental health treatment is a marker of perceived stigma or other psychological barriers.

Large-scale public education programs, such as the NIMH Depression Awareness, Recognition, and Treatment program

(50), hold promise for reducing these psychological barriers by increasing awareness of and comfort with both mental disorders and their treatments. Demand management strategies developed by health educators may also help reduce barriers to initiating and remaining in treatment

(51,

52). Increasing the patient-centeredness of mental health treatments, which is becoming important in other areas of medicine

(53), may also be helpful. The new Consumer-Oriented Mental Health Report Card

(54) and the new requirement of ongoing patient satisfaction surveys for Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set accreditation

(55) are encouraging innovations that might stimulate development along these lines. It might be that a combination of such interventions will be needed to increase the proportion of patients with mental disorders who remain in treatment long enough to complete adequate courses and ultimately experience improvements in their health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The National Comorbidity Survey is a collaborative investigation of the prevalences, causes, and consequences of psychiatric disorders in the United States (Ronald C. Kessler, principal investigator). Collaborating sites and investigators are as follows: Addiction Research Foundation (Robin Room); Duke University Medical Center (Dan Blazer, Marvin Swartz); Harvard University (Richard Frank, Ronald Kessler); Johns Hopkins University (James Anthony, William Eaton, Philip Leaf); the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry (Hans-Ulrich Wittchen); the Medical College of Virginia (Kenneth Kendler); the University of Michigan (Lloyd Johnston, Roderick Little); New York University (Patrick Shrout); SUNY Stony Brook (Evelyn Bromet); the University of Miami (R. Jay Turner); and Washington University School of Medicine (Linda Cottler, Andrew Heath). The Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey is an epidemiologic survey designed to assess the prevalence of psychiatric disorders and associated risk factors, disabilities, and service utilization across the Province of Ontario (David R. Offord, principal investigator). Collaborating Mental Health Supplement agencies and investigators are as follows: the Ontario Mental Health Foundation (Dugal Campbell); the Clarke Institute of Psychiatry (Paula Goering, Elizabeth Lin); McMaster University (Michael Boyle, David Offord); and the Ontario Ministry of Health (Gary Catlin).