A Case of “Pfropfschizophrenia”: Kraepelin’s Bridge Between Neurodegenerative and Neurodevelopmental Conceptions of Schizophrenia

Case Presentation

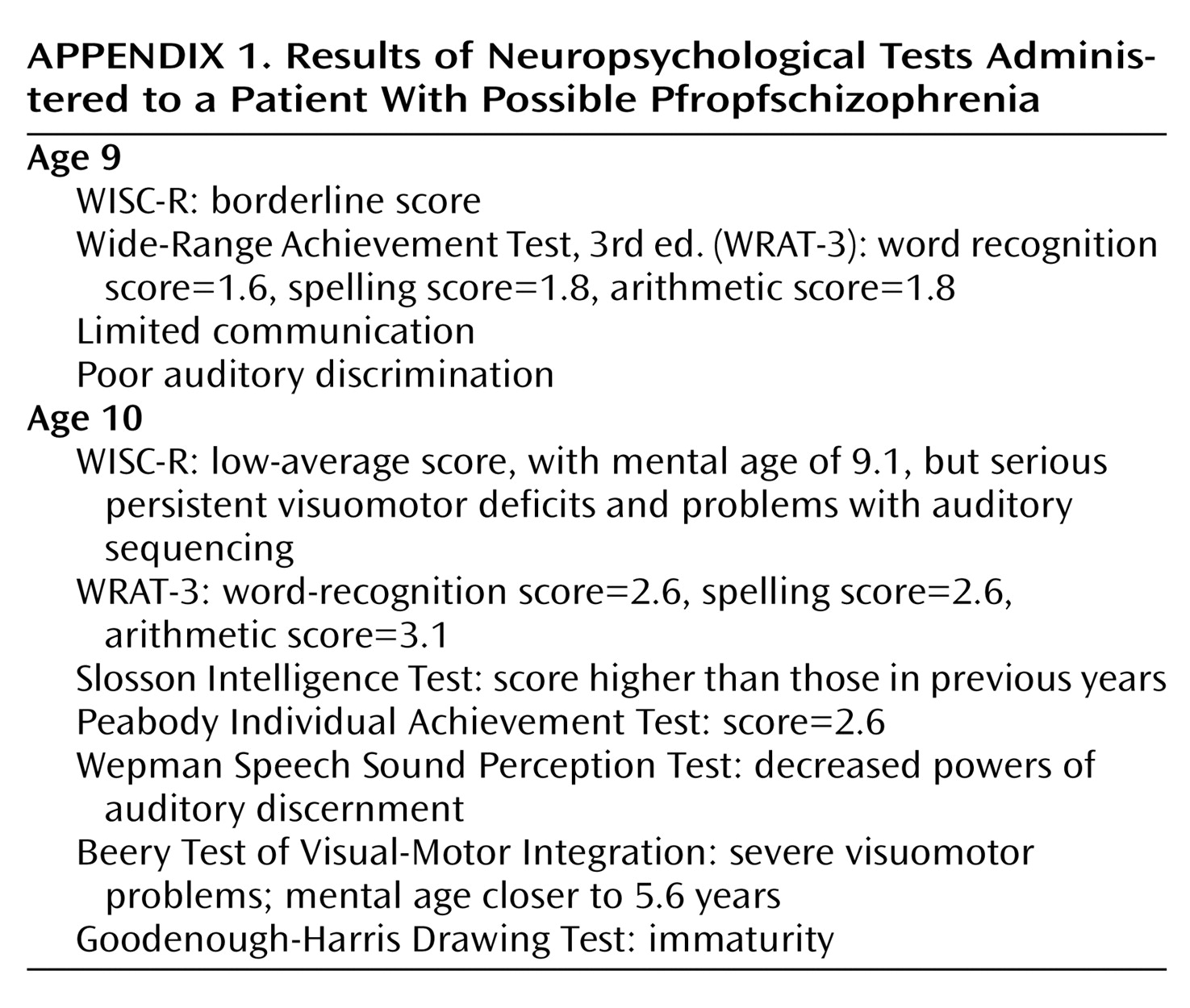

Mr. A was a 29-year-old African American man who was transferred to the day hospital and shelter of our health center (the index admission) after his third lifetime inpatient psychiatric admission—a 7-month, court-ordered forensic evaluation at a nearby state mental health center. On admission he stated, “I’m here to treat my paranoid schizophrenia.”Mr. A had been stable since his last inpatient admission 18 months before that admission. Although psychiatric care had been arranged for him at that discharge, he had not followed up. He had lived with his mother and brother without any psychiatric treatment at all. His mother described him as having been “his usual self, happy-go-lucky.” His brother’s social worker said that he had always been polite and interested in work during this period. He had had a job in a dry-cleaning facility, but he had quit because he believed the other workers were teasing him. Fifteen months before psychiatric admission, his mother had brought him to the emergency room when he would not open the door to his room—and he was discharged to his home.As a result of an argument over cigarettes (his mother had refused to give him one of her own) 7 months before admission, Mr. A assaulted and battered his mother with the intent to kill her. He felt justified in his attack but understood that it was wrong. He was arrested and brought to court, where he was referred to the state inpatient forensic unit for evaluation. Test results were negative for substances of abuse in his urine and serum at the time of admission. Upon arrival on the inpatient unit, Mr. A was uncooperative and unwilling to participate in examinations. Because he was selectively mute, lying still, and unresponsive to attempts at engagement, he was described as “catatonic.” His affect was without emotion, and he described his mood as “casual.” When he did speak, he produced thoughts that were tangentially associated. At other times he produced meaningless word fragments and syllables. He complained of hearing “voices” from outside of his head telling him to “watch out.” He was scared that his mother wanted to hurt or kill him. Mr. A reported no sadness, he had no periods of inflated self-esteem, and he did not have a lessened need for sleep. He reported no suicidal, homicidal, or violent ideation. He reported no feelings of guilt, no lack of concentration, no decreased libido, no change in appetite, no change in interest in pleasurable activities, and no fatigue in the weeks before the attack.Once admitted to the forensic unit, Mr. A stayed in his room under the bed sheets for weeks. He was given risperidone, but it was discontinued because it caused a rash. Later he was given quetiapine, up to 700 mg/day. At that point there was little progress in terms of socialization and affect, but these aspects of his presentation improved with the additional administration of haloperidol on a daily basis. Later he was given propranolol for akathisia. He began to venture from his room and to socialize more. As he began to transition to the day hospital, he also began to visit his mother at her home, to which she did not object.Mr. A’s past psychiatric history began at age 16, 13 years before the current admission, when he was referred to the diagnostic clinic at a local hospital after an unarmed robbery. Results of an examination had discerned no thought disorder or perceptual disturbances. He received the diagnoses of conduct disorder and developmental learning disorder. Outpatient treatment was recommended, but he did not follow up. One year later he had a “breakdown,” during which he punched his hand through a glass window, but he received no care at the time. He may have been well for the 8 years between that incident and an episode 4 years before admission (at age 25) in which he cut his left wrist intentionally while cooking but sought no psychiatric care.Mr. A’s first psychiatric hospitalization was at age 27, 18 months before the current admission. He initially was brought to the emergency room because of bizarre behavior at home, including talking to, and swinging sticks at, persons not present. He was mute and curled into a fetal position on a stretcher when he was evaluated in the emergency room. He was referred to an inpatient unit, where he was also described as “catatonic.” He was uncooperative and unresponsive, stayed in bed with the covers over his head, and had a clear sensorium. He responded to treatment with oral fluphenazine, 10 mg/day, and he eventually stated that stresses in his life had made him upset. He was discharged while taking fluphenazine. He did not take it after discharge, and he did not keep his outpatient psychopharmacology appointment. He was readmitted 5 days later when he was brought to the emergency department from a bank in which he had engaged in an altercation with a teller, later noting a wish to harm her. This second hospitalization lasted 3 months. During this time his psychosis was unresponsive to fluphenazine, risperidone, and haloperidol, but it dramatically responded to olanzapine. Results of an EEG at that time were normal. After the second discharge, he failed to follow up.Mr. A occasionally used alcohol and had tried crack cocaine and marijuana one or two times each. His drug of choice was marijuana, although he may not have used it within 8 years of admission.Mr. A’s medical history was significant for intrauterine exposure to his mother’s severe iron-deficient pancytopenia (her hematocrit measurement hovered around 29%), which was unsuccessfully treated with massive doses of iron. His mother also had hyperemesis gravidum, which was treated with chlorpromazine. She gained only 15 lb during his entire gestation; only 2 lb were gained in the third trimester.Through much of his infancy and childhood, Mr. A suffered from the effects of malnutrition. At 2 months he was diagnosed with failure to thrive secondary to malnutrition, and at 10 months he was admitted to the hospital for viral meningitis, failure to thrive, iron-deficient anemia (with a hematocrit measurement of 26%), and pneumonia. He experienced a febrile seizure at 12 months. At 18 months his weight was less than the third percentile of the normal range, at which point he was treated for 5-minute generalized tonic-clonic convulsions with fecal incontinence. From ages 5 to 7 he had seizures that ceased without medication.Mr. A’s medical history also included asthma. He had a positive reaction to the purified protein derivative of tuberculosis and so was administered pyridoxine and isoniazid therapy in the months before the current admission. His HIV status was unknown, but he had few risk factors for HIV given his never having had sexual contact and his never having injected drugs of abuse.Mr. A walked by age 1. He repeated the first grade. In the second grade, a teacher noted that he had “perceptual problems in the visual area, particularly visuomotor skills and possibly auditory processing problems combined with attention-getting behavior, [and] hyperactivity,” and a psychologist observed that he did well with individual attention but had poor language skills and problems with visuomotor control. He had “no” friends, and peers did not allow him to play with them. He was seen as guarded and defiant, and he teased others for attention. In class he also repeatedly fell asleep, awaking “incoherent.” He was, however, good at telling stories. Neuropsychological studies were performed at ages 8 and 9, the results of which are noted in Appendix 1. The results showed his language skills to be “depressed.” Problems in visuomotor control were again noted, particularly in terms of fine motor skills. Gross motor skills, however, were normal. He also did not pass a hearing test at that time. He repeated seventh grade twice. He attended school until the ninth grade and then was expelled after “problems with aggression, including bullying younger kids,” and an attempted robbery.Mr. A was the older of two sons of the same parents. His father was not present for almost all of his life. His mother had seven brothers and seven sisters; almost all of them and their respective families lived in the city housing project in which Mr. A, his mother, and his brother lived. Mr. A and his mother stated that they were “different” from the other family members and tried to keep an identity separate from them. All were, according to Mr. A’s mother, of normal height and mental capacity. Mr. A had never been sexually active, but he stated that he was heterosexual. He enjoyed playing games, such as basketball and ping-pong. The two brothers and their mother lived in an “extremely” impoverished manner, and until recently, they had had no telephone in the home. The mother supported all three of them with monthly funds that she received for the care of Mr. A’s brother.Mr. A’s interactions with the law included an arrest as a teenager for possession of a gun. After involvement in an unarmed robbery, he was placed in the supervision of the state and put in a number of foster and group homes and in an institution for juvenile delinquents until age 17.Mr. A’s family history was significant for low intellectual functioning in both his mother and brother. His mother had scored in the 50s on the WAIS-R intelligence test. Mr. A’s brother was born prematurely and at a low birth weight after a pregnancy that had also been complicated by pancytopenia and hyperemesis gravidarum. The brother’s gestation was also compromised by a varicella infection in the weeks before birth. At delivery the brother was a “floppy-blue immature male” with an Apgar score of 4 at 1 minute and 7 at 5 minutes. At 10 minutes he grunted and flared and was cyanotic while breathing room air. The results of Stanford-Binet testing at age 17 showed that his overall intelligence was far below average; he had a score equivalent to a mental age of 6 years and 6 months. His basic academic skills were at a first- and second-grade level. Significant delays had been noted in his receptive vocabulary and visuomotor integration. In the classroom, he was noted to be “severely hungry” for attention, but he was not noted to be aggressive. Neuropsychological testing at age 22 confirmed an intellectual age of 5–7 years.Upon examination for the current admission, Mr. A was noted to be a thin, short, African American man who appeared to be younger than his stated age and who wore athletic clothing and berets or hats. He had a moustache that he allowed to grow long, but he had little other facial hair. His hair was braided; he usually slouched in a chair. There were no appreciable extrapyramidal movements, no tremors, and no asterixis. He produced no abnormal movements. He was cooperative when he was not distracted. His speech was often slow; many words were poorly pronounced. His mood was “great” (which was incongruent with his life situation). Usually his affect was constricted and flat, but he had occasional, inappropriately large smiles. He produced loose associations, often making statements in groups that were entirely out of context. He described anxiety by saying, “Someone’s going to bite me,” when he was walking down a hallway; he reported no “anger” at that time. He did not report, and did not seem to be responding to, internal stimuli. He knew that he had a mental disorder but seemed unable to grasp its effect on his life. He reported no intent to harm himself or others, including his mother. His arousal level ranged from sleepy to awake; he was oriented to person, place, and time. He could spell “WORLD” but only backward: “D-L-W.” He recalled two of three objects immediately, which improved to three after prompting. According to Mr. A, the similarity between a bird and plane was that “They fly.” The results of tests performed at admission included normal thyroid levels. His hematocrit was in the anemic range (37.7%), and he had a mean corpuscular volume of 78 μm3/cell.Karyotyping of Mr. A, his brother, and his mother produced a sex-specific normal result for each. A fluorescent in situ hybridization study with use of the Tuple1 probe performed on region 22q11.2 of Mr. A’s chromosomes, the velocardiofacial syndrome area, found no abnormalities.Neuropsychological tests performed while Mr. A was taking haloperidol and quetiapine showed overall intellectual functioning in the “extremely low” range. His functioning was borderline in terms of vocabulary and visuoconstruction on the WAIS-III and on measures of attention, verbal learning and memory, visual analysis, and fine motor speed, but his functioning was worse in the executive domains, such as problem solving, planning, reasoning, abstraction, and mental flexibility, and he was “slowed” in his thinking. His overall WAIS-III scores were full=63, verbal=65, and performance=66. Mr. A had poor spatial reasoning and scored lower than the first percentile for such tasks. He could not understand the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (10). On the Trail Making Test (11), he took 50 seconds to perform the first trial (with no errors) and 158 seconds to perform the second (with two errors). Marked impulsivity and a low tolerance for frustration were observed. On the other hand, he showed relative strength in reading single words, naming categories, and recognizing on verbal learning tasks. His scores on the Wide-Range Achievement Test, 3rd ed. (12) placed him in the 14th percentile, consistent with “higher premorbid function” in the time before the current illness. It was felt that there was no evidence for a developmental learning disorder given the consistency of his skills. He demonstrated paranoid tendencies but no other thought disorders.On the basis of his history and examination, Mr. A was admitted to the day hospital and continued taking the same medications. Results of random drug toxicology screens were negative. He remained in behavioral control. Very often his interactions with other patients consisted of annoying them “for attention,” he noted. He continued to complain of not having gotten enough sleep, despite sleeping more than 10 hours per night, so his dose of quetiapine was reduced from 500 mg to 400 mg at bedtime.A family meeting occurred on the unit that was attended by the authors, Mr. A, his mother, his brother, and his brother’s social worker. During the meeting Mr. A’s mother minimized the violence that Mr. A had inflicted upon her at the onset of the current episode. Strangely, during the meeting Mr. A was noted by his brother’s social worker to be more vociferous and arrogant than ever before. He interrupted and dismissed his mother. Mr. A seemed to tease his brother, having the two shake hands repeatedly while the others spoke. His brother made some eye contact but produced no speech and often smiled on making eye contact.After 4 months Mr. A left the day hospital and all care at our health center, although follow-up care had been recommended and established. At the time of this writing, he was living with his mother and brother, getting disability payments by means of a representative payee, and receiving no further care.

Discussion

Schizophrenia and Mental Retardation

Intelligence and Psychopathology

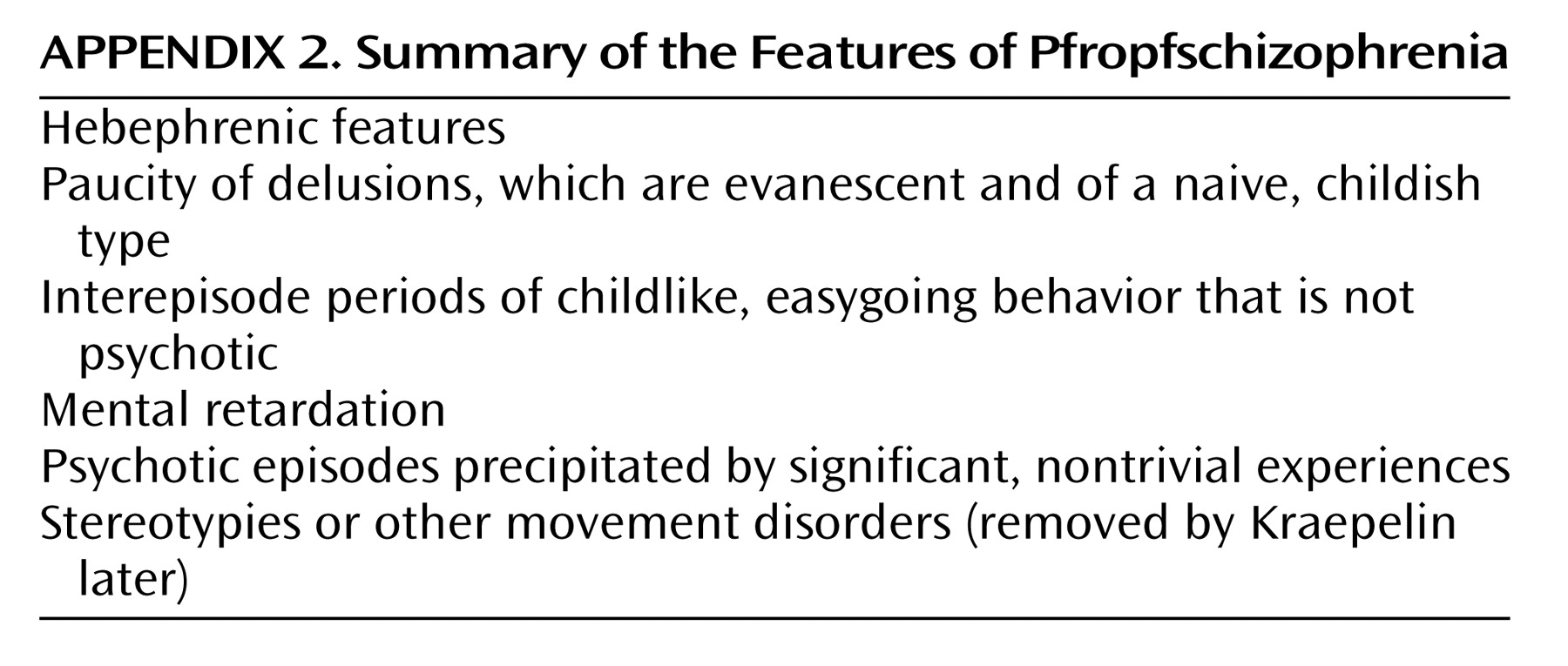

Pfropfschizophrenia

Conclusions

Footnote

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Authors

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBGet Access

Login options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).