It is estimated that one of every five children and adolescents in the United States has a mental disorder

(1–

3); left untreated, these disorders are often debilitating

(4–

7). Empirically validated treatments exist for many mental disorders, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), conduct disorder, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders

(4–

9). However, recent health policy discussions concerning the mental health needs of children and adolescents have been limited by the lack of national data on rates of mental health service use and unmet need for such services

(10).

Populations that may be particularly vulnerable to lower rates of use of mental health services include ethnic minority youth and the uninsured. Previous studies on child mental health service use have largely been based on regional data or data from insured populations and have yielded a mixed pattern of results regarding possible disparities in service use. For example, in a sample of children in New Haven, Conn.

(11), African American and Latino children had lower rates of mental health service use than did Caucasian children. A study of a group of insured children

(12) found lower rates of service use for African American but not Latino children than for white children. However, in the Great Smoky Mountains Study

(13), African American children did not differ from Caucasian children in service use. How insurance status affects use of child mental health services is also unclear

(14,

15).

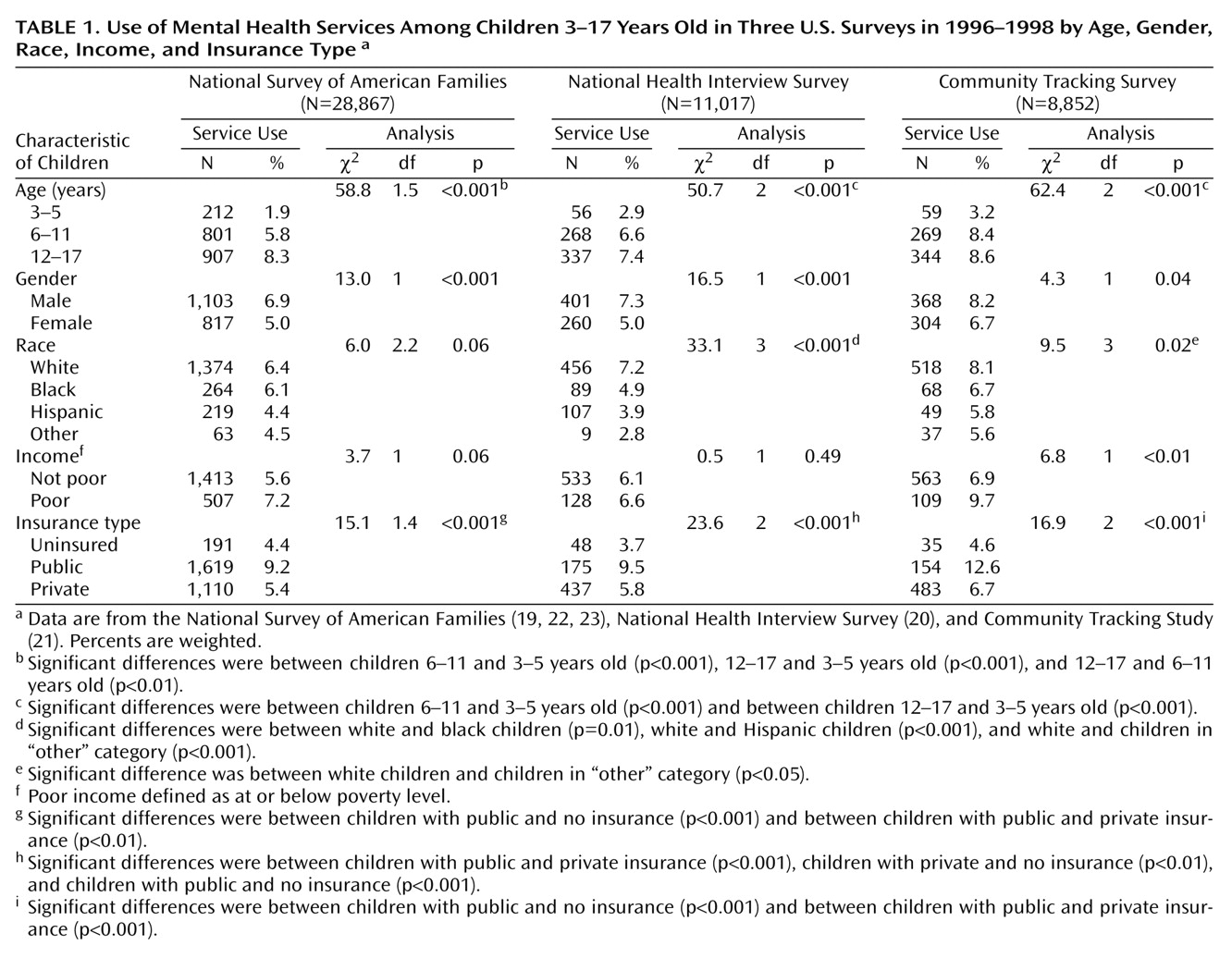

To study rates of use and unmet need for children and adolescents in the United States, we primarily used data from the National Survey of American Families, a large nationally representative sample, and attempted when possible to confirm findings across several national data sets. We hypothesized that the rate of overall mental health service use for children is low and that most children who need a mental health evaluation do not receive any services (our definition of unmet need). In addition, we hypothesized that minority and uninsured children have greater rates of unmet need for a mental health evaluation than their white and insured counterparts.

Method

Data Sources

We provide separate cross-sectional analyses of three nationally representative household samples of U.S. civilian, noninstitutionalized children 3–17 years old. Full descriptions of the study designs are available elsewhere

(19–

21). Because methods differ across surveys, we examined rates of use and ethnic and insurance status within each survey and then considered the consistency of conclusions across data sets. The main data set for this study is the National Survey of American Families

(19), with supporting analyses from the National Health Interview Survey

(20) and the Community Tracking Survey

(21) when applicable.

The main data set for the study, the 1997 National Survey of American Families

(19,

22,

23), sampled more than 44,000 households and 28,867 children, with larger shares of the sample from 13 states that account for more than half of the U.S. population and a smaller sample of the balance of the nation to permit national estimates. The most knowledgeable adult in the household (95% were parents) provided information about the sampled child, but emancipated minors provided their own information. The survey oversampled people with low incomes. Interviews were conducted in Spanish and English. The response rate was 65.4%.

The 1998 National Health Interview Survey

(20) sampled 38,209 households, including 11,017 children, using a multistage stratified cluster design and oversampling African Americans and Latinos. A knowledgeable adult in the household provided information about the randomly selected child. The response rate was 82.4%. The 1996–1997 Community Tracking Survey

(21) sampled 32,732 family insurance units, which included 8,852 children and adolescents aged 3–17. Sixty sites were randomly selected on the basis of metropolitan statistical areas, and sites were stratified by region and size. Households were randomly selected. To increase the precision of the national estimates, a smaller supplemental sample was included in this survey that randomly selected households from the 48 continental United States. An adult informant from each family insurance unit provided information about the randomly selected child. Interviews were conducted in English and Spanish. The overall response rate was 65.0%.

Outcome Measures

Each survey elicited information on use of child mental health services over the preceding 12 months. For each data set, we derived a dichotomous variable indicating whether the child had received any mental health care. The National Survey of American Families respondents were asked how many times the child had received mental health services from a doctor, mental health counselor, or therapist, excluding visits for smoking cessation and treatment for substance abuse. The National Health Interview Survey asked whether the adult respondent had seen or talked to a mental health professional about the child. The Community Tracking Survey asked if the child had received any care from a mental health professional.

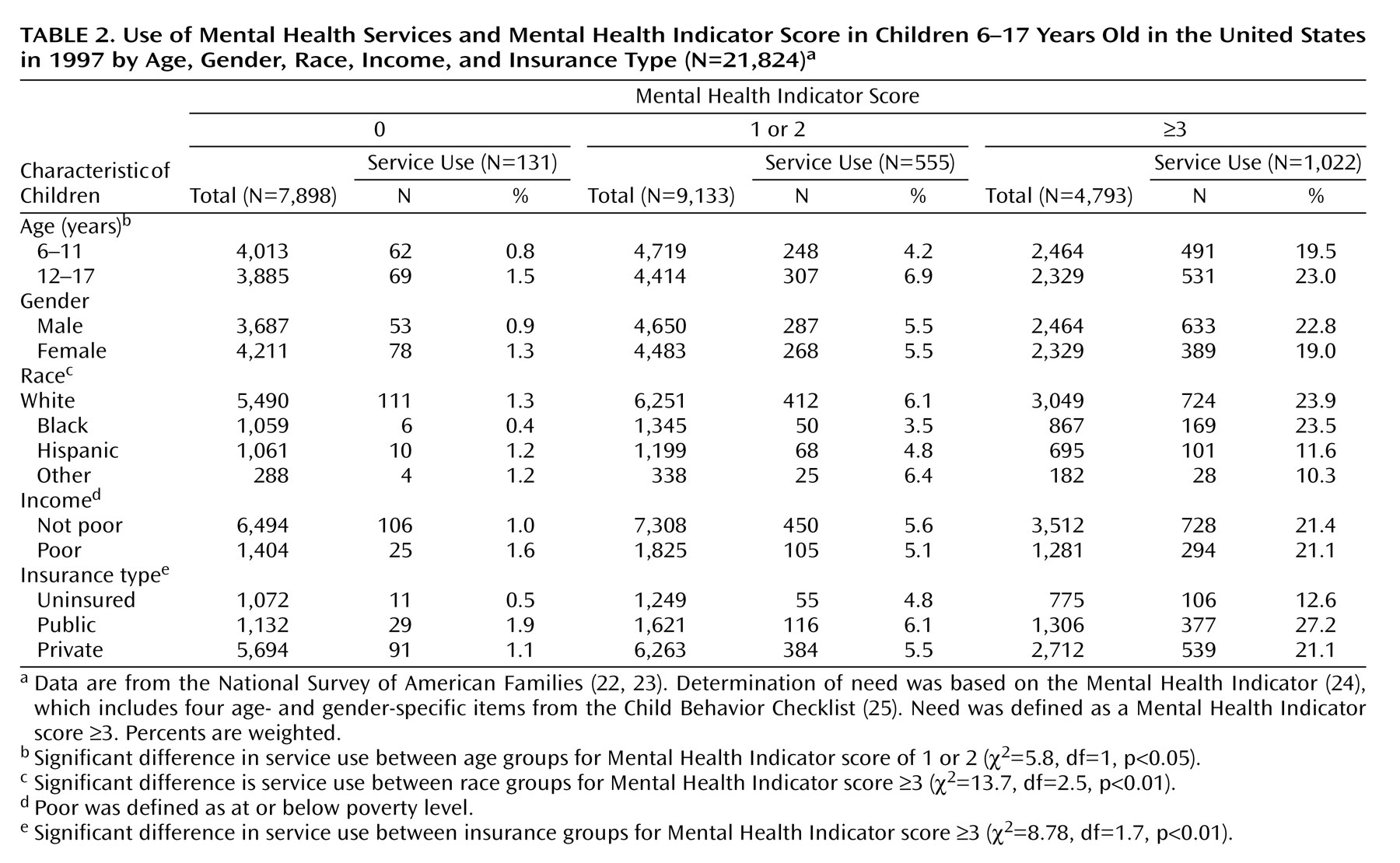

Children were categorized as having unmet need if they had exceeded a cutoff point on a mental health screening measure (described later in this article) but had not received any mental health services in the past 12 months. Need was not measured in the Community Tracking Survey.

Main Independent Variables

The adult respondent reported the race of each child, which was categorized as white, black, Hispanic, or other; the white and black groups excluded subjects of Hispanic background.

The National Survey of American Families defined current child health insurance coverage as public insurance (Medicaid, Medicare, military insurance, and Indian Health Service insurance), private insurance (employment related or directly purchased), or no insurance. We grouped the National Health Interview Survey and Community Tracking Survey data into similar categories. For children with multiple coverages, a hierarchy was used to assign a child to the applicable category (private insurance, then public insurance, followed by no insurance). Whether a child’s health insurance included mental health coverage was not elicited in the surveys.

The measure that estimates need for a mental health evaluation, included in both the National Survey of American Families and the National Health Interview Survey, is the Mental Health Indicator

(24), which comprises selected items from the Child Behavior Checklist

(25). The original Child Behavior Checklist is a standardized questionnaire of parent-rated child behavior over the preceding 6 months. Child Behavior Checklist items that best discriminated between demographically similar children who were or were not referred for mental health services were chosen for inclusion in the Mental Health Indicator, which is thus a measure of the need for clinical evaluation. The Mental Health Indicator includes four age- and gender-specific items from the Child Behavior Checklist rated on a scale of 0, 1, or 2, for a total possible score of 8; higher scores represent greater need.

Validation of the Mental Health Indicator was based on receiver operator characteristic analysis of Mental Health Indicator scores compared with external criteria such as a lifetime history of ADHD, mental retardation, learning disability, and past use of mental health services

(26). The recommended cutoff point for defining a level of need meriting evaluation is a score of 2, but to avoid concerns about overinclusion of minor or transient symptoms, we relied on a more stringent criterion of 3 or higher for analyses of unmet need, with specificity ranging from 88% to 90% for each age-gender category

(26). Mental Health Indicator scores are available in the National Health Interview Survey for children 4 and older and in the National Survey of American Families for children 6 and older. The Community Tracking Survey has no child mental health need indicator, so we used the Community Tracking Survey to describe rates of services use only.

Demographic and Parent Characteristic Variables

Demographic information included the child’s age and gender and the household income. The U.S. Census poverty ratio was used to assess total family income in each data set. Poor was defined as a ratio below 1.0, indicating that the family income was below the poverty level. In the National Health Interview Survey, this information was missing for 20% of the children, but we imputed the variable using other sociodemographic information.

The designations of West, South, Midwest, and Northeast for regional location were based on the U.S. Census statistical groupings

(27).

The adult’s level of education was categorized as less than high school, high school, some college, or 4 or more years of post-high-school education. Household composition was defined as single-parent household or non-single-parent household. Emancipated minors (0.2% of the youth) were grouped with non-single-parent households for analyses. Mental health functioning of the adult respondent was determined by using the five-item Mental Health Inventory

(28), which assesses psychological well-being in adults. Scores on this instrument range from 25 to 100, and higher scores indicate better mental health. A cutoff of 67 or below indicates poor mental health, approximately the lowest 20% of the general population

(29).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses of service use by age group, ethnicity, and insurance status were conducted for each data set separately. We used statistical tests appropriate for the complex sampling design of each data set. We used a modified Pearson’s chi-square statistic

(30) to test the independence of two categorical variables in the National Survey of American Families data, and a Wald statistic

(31) was used to test independence for each two-way table in the National Health Interview Survey and Community Tracking Survey data. For each data set, standard errors of individual coefficients were calculated by using a jackknife replication method

(32), which took into account the complex weighting schemes.

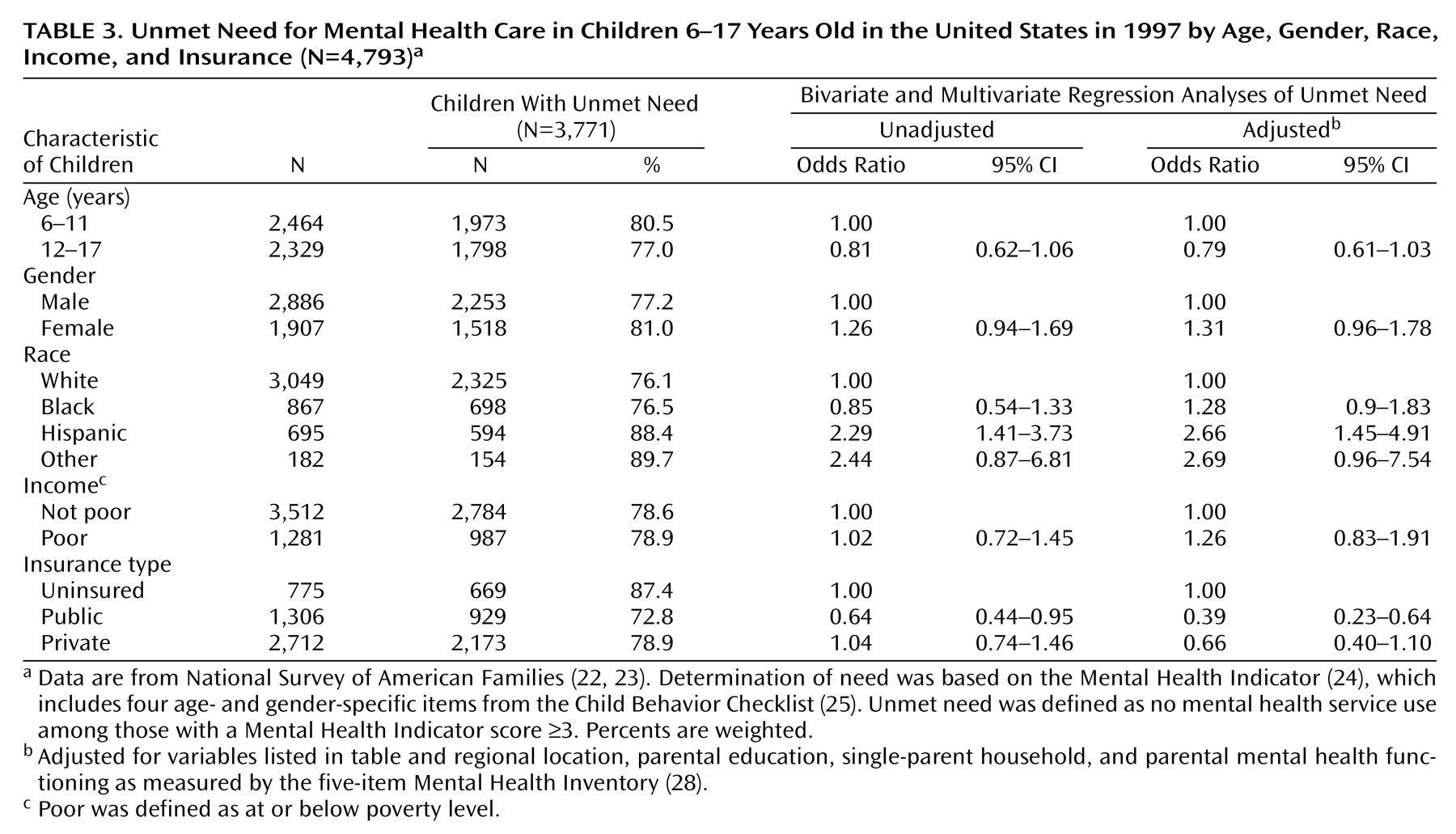

We used logistic regression in both the National Survey of American Families and the National Health Interview Survey for the unadjusted analyses of unmet need, which estimated the probability of having no mental health care in a year for those children 6–17 years old who met criteria for need (Mental Health Indicator score of 3 or higher). To examine the effect of race and insurance characteristics on unmet need while controlling for other factors, we performed multiple logistic regression using only the main data set, the National Survey of American Families. Following the Aday and Andersen health service model

(33), we included covariates shown in previous studies

(11,

12,

15,

34–39) to be significantly associated with service use such as predisposing factors (age, gender, race, parental education, single-parent household, parental mental health), enabling resources (income, insurance, and regional location), and child’s mental health need.

Statistical analyses were performed by using WesVar software

(40) for the National Survey of American Families and SUDAAN software

(41) for the National Health Interview Survey and Community Tracking Survey. All estimates are weighted to be nationally representative.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to provide national estimates of use of child mental health services and the unmet need for such services. Overall, the data suggest that 6.0%–7.5% of U.S. children receive mental health services, a result confirmed across three data sets. We also found that most children and adolescents who need a mental health evaluation do not get any mental health care in a year, and this was more pronounced for Latinos and the uninsured. “Need” in this study is based on a screening measure that estimates need for clinical evaluation, not necessarily indicating that treatment or intensive services are warranted. Nevertheless, we applied a more stringent cutoff point than recommended for these national surveys specifically to avoid concerns that we would comment on high unmet need for a group largely consisting of milder cases of need.

Another issue is whether we could have underestimated levels of use or need being met because of the brief utilization question in these surveys and emphasis on specialty mental health services. Although this is a general estimate of service use for mental health problems, the service use item in one survey did encompass primary care and nonpsychiatric care for mental health problems, yet conclusions were similar about levels of use and unmet need across data sets even though they differed in methodology. In addition, even if the rate of overall unmet need is somewhat lower, there is no reason to assume that comparative estimates of use or unmet need (i.e., across ethnic groups) are biased.

With these caveats in mind, we found that only 21% of the children who need a mental health evaluation receive services. This suggests that about 7.5 million children have an unmet need for mental health services in the United States, largely confirming findings from others

(37). At a time of continuing concern over the high costs of health care, including mental health care, it may be difficult to focus national policy debates on the implications of such a high rate of unmet need among children. However, the implications for children and adolescents with untreated mental health problems can have major developmental consequences. For example, longitudinal studies have found that depressed children are at greater risk for later suicidal behavior, poor academic functioning, substance abuse, and unemployment

(42), necessitating improvement in access to effective mental health prevention and early intervention for youth and their families.

Our finding that Latino children have even greater rates of unmet need than white children is particularly concerning given the national estimates suggesting that Latino adolescents have higher rates of suicidal thoughts, depression, and anxiety symptoms and greater rates of dropping out of high school than white adolescents

(43). As described in the Surgeon General’s Report on Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity

(44), services could be improved for Latinos by dealing with barriers such as financial constraints and lack of bilingual bicultural mental health providers. In examining birthplace of parent, we found that unmet need did not significantly differ between children with non-U.S.-born parents (N=79, 93%) and those with U.S.-born parents (N=515, 88%) (χ

2=1.42, df=1, p>0.05).

Additional research is needed to clarify the mechanisms underlying disparities in unmet need for mental health care among children because these different mechanisms have unique intervention and policy implications. For example, differences in parental attitudes may require educational interventions, but community differences in service availability require policy targeted at developing resources. Although Latino children had the highest rates of unmet need, the rates for white children were also quite high, emphasizing the general conclusion that there is a high rate of unmet need nationally for mental health care among children and adolescents.

We also found that uninsured children had higher rates of unmet need than publicly insured children, suggesting that Medicaid and other public insurance programs offer an important safety net, but we cannot comment as to whether the uninsured children in these studies were eligible for but not enrolled in public programs such as Medicaid or the State Children’s Health Insurance Program. Expanding insurance coverage to currently uninsured children, as proposed by the State Children’s Health Insurance Program

(45), could be an important avenue for addressing unmet need

(46). However, implementation of the State Children’s Health Insurance Program has been variable across states

(47), with lower enrollment among black and Hispanic children than among white children

(48). Our findings for children differ from those found in adults

(18), in which the uninsured had less access than the privately insured, but the lower differences by insurance status among children could be partly due to the high level of unmet need across insurance groups among children.

We provide only a first sketch of national mental health care among preschoolers, who are referred most often for behavioral problems such as aggression, defiance, and overactivity

(49,

50). Our descriptive findings suggest that the vast majority of preschool children with mental health needs in the United States do not receive services for those problems. The more talked-about public concern is the high rate of psychotropic medication use in young children

(51,

52), but an even greater problem may be the lack of any evaluation or care for children with mental health problems. Further research is needed to confirm these findings on larger samples of young children and to determine whether unmet need is due to parent preference, unavailability of services, or problems in recognizing problems or identifying specialists for this age group

(53).

As we have suggested, this study is limited by the use of parent-reported screening measures of need and service use; national studies using diagnostic measures for specific childhood disorders, level of impairment, and type and quality of service use are needed. In addition, only noninstitutionalized children were surveyed, which excludes those living in out-of-home placements and the homeless, who may have higher rates of mental health need than the general population

(54–

56). However, our overall estimate of unmet need is similar to estimates based on diagnostic measures

(37), and our findings concerning the use of services were consistent across three independent national data sets.

This study reinforces the finding of the recent Surgeon General’s report

(10) that there is substantial unmet need for child mental health care in the United States, which is particularly acute for some minority and uninsured groups.