In 1866, the British surgeon John Eric Erichsen first described a syndrome consisting of cognitive impairments and psychosomatic symptoms that occurred in survivors of railway accidents

(1). He reported that this condition was frequently associated with a deteriorating business sense. Erichsen’s “railway spine” is regarded as one of the first accounts of the social consequences of accidental injuries. More recently, it has been pointed out that in addition to physical impairment and psychiatric morbidity, accidental injuries inevitably cause social disability, affecting work, leisure, and family life

(2). However, the determinants of time taken off work because of accidental injuries remain unclear. When we take into account the frequency of accidents worldwide and their effect on society in terms of the loss of manpower through the temporary and permanent inability to work, the scarcity of published research on this issue is surprising.

Some studies on the social consequences of accidents have focused on litigation and “accident neurosis”

(3–

5). Other authors have reported that psychological morbidity after injury have compromised the patients’ return to work

(6,

7). Nevertheless, little is known to date about the relationships between injury severity, patients’ psychological reactions, and their appraisals regarding the accident and its consequences on one hand and the duration of leave because of the accident on the other hand. It has been shown in patients after myocardial infarction that optimistic beliefs concerning their illness predicted an earlier return to work

(8). In accident victims, a higher extent of the patients’ perceived control over convalescence seems to be associated with a shorter hospital stay

(9).

The present study aimed to identify predictors of the number of days of leave taken in a group of accident victims who sustained severe, mostly life-threatening physical trauma but no severe head injuries. To study the effect of the accident selectively, we collected a group of patients who were free from preexisting mental disturbances. We hypothesized that objective accident-related measures and psychosocial factors, such as the patients’ early psychological reactions and accident-related cognitions, would be equally important predictors of time taken off work.

Method

Participants and Study Design

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Zurich. All participants had sustained accidental injuries that caused a life-threatening or critical condition requiring their referral to the intensive care unit of the trauma department at the University Hospital of Zurich

(10–

12). The University Hospital of Zurich accepts regional referrals of all kinds of accident victims. In addition, as our center is a recognized trauma center, patients with severe and complicated accidental injuries are referred from all over Switzerland and southern Germany. An Injury Severity Score

(13) of 10 or more and a Glasgow Coma Scale

(14) score of 9 or more were required, thus excluding all patients with severe head injuries. Furthermore, the patients had to be 18–70 years of age and able to take part in an extensive interview within 1 month of the accident regarding both their clinical condition and fluency in German. All interviews were conducted by an experienced internist who had been involved in research for a number of years and was thoroughly trained in traumatic stress research. Patients suffering from any serious somatic illness or who had been under psychiatric treatment immediately before the accident and/or those who showed marked clinical signs or symptoms of mental disturbances that were obviously unrelated to the accident were excluded. Patients for whom a history of mental disorder had been elicited during the interview were discussed in detail with the first author before a final decision was made regarding their inclusion. Sixteen patients were excluded for this reason. In addition, all patients who sustained their injuries as a result of a suicide attempt or from a physical attack were excluded from the study.

During a recruitment period of 18 months, all patients in the intensive care unit were consecutively screened; 135 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria. After the study was completely described to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained from 121 patients; 14 (10.4%) refused to participate. Follow-up interviews were performed at 12 months, ±3 weeks, after the trauma. Fifteen (12.4%) of the 121 patients were lost to the study during the follow-up period: one patient committed suicide, one returned to her country of origin, and 13 refused to participate in the follow-up. Thus, 106 patients participated in the 1-year follow-up. The 14 patients who refused to participate in the study did not differ significantly from our group regarding sex, age, or Injury Severity Score and Glasgow Coma Scale score. However, significantly more work-related accidents were found among the refusers (refusers: seven [50%], group: 13 [12.3%]) (p<0.01, Fisher’s exact test). The 15 dropouts did not differ significantly from the 106 participants regarding sociodemographic characteristics or accident-related variables. Finally, three patients were supported by a pension, one patient was a homemaker, and two patients with incomplete data had to be excluded from the analyses regarding fitness for work. Thus, all further analyses in this article were performed on a final group of 100 patients.

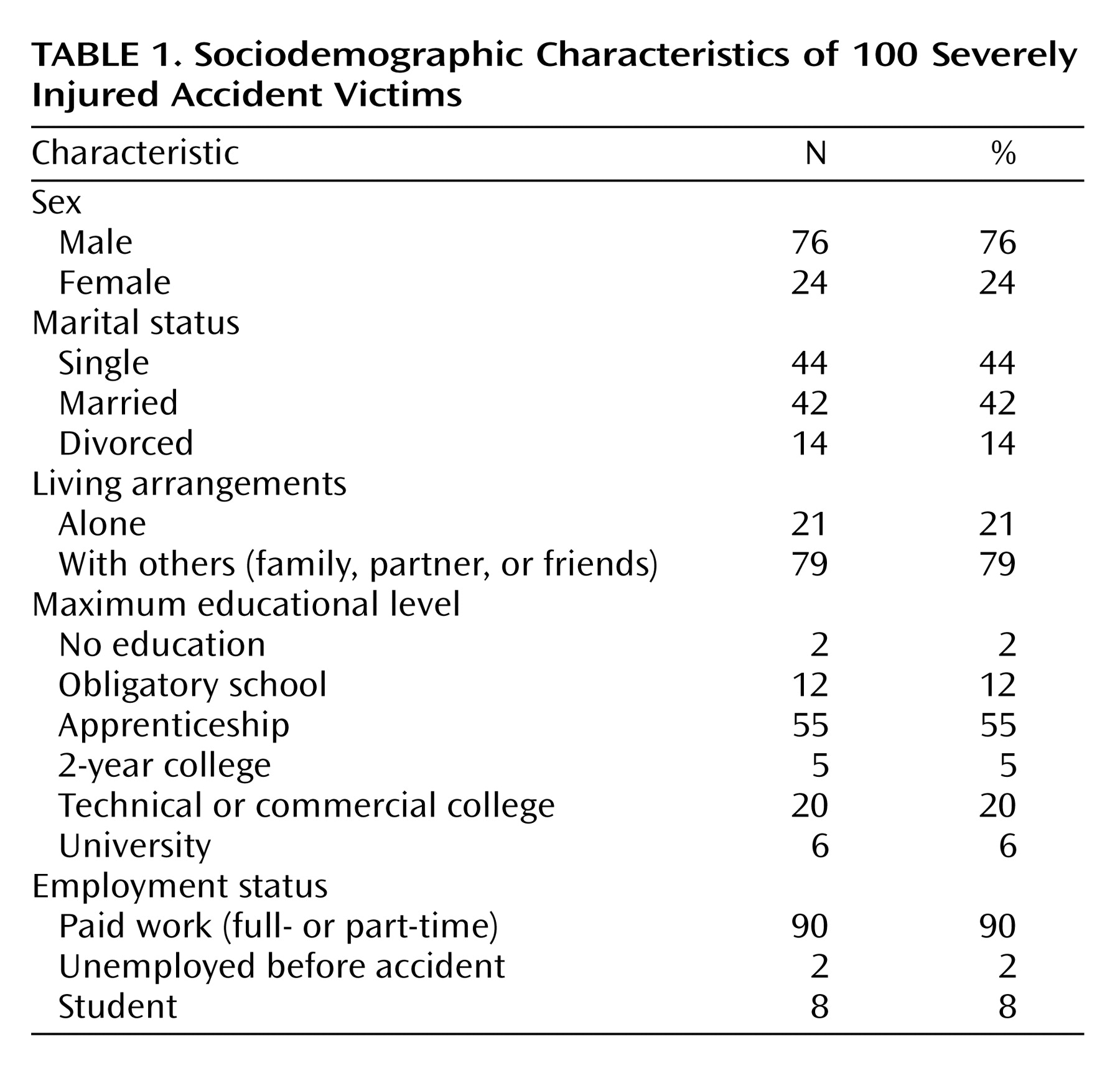

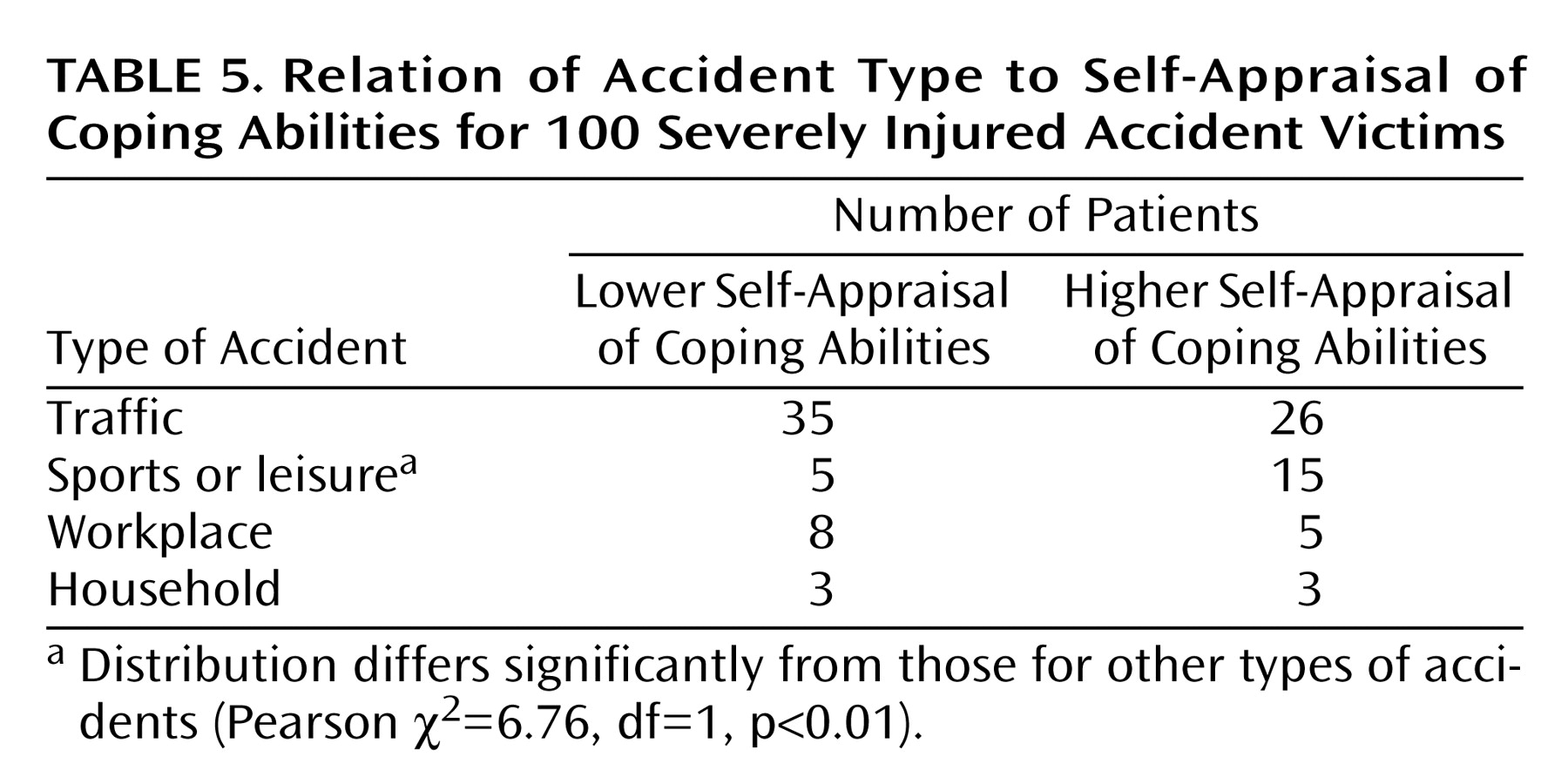

Sociodemographic characteristics of the group are presented in

Table 1 (mean for age was 36.8 years, SD=12.5). Traffic accidents were most frequent (61 patients), followed by severe sports or leisure accidents (20 patients), accidents in the workplace (13 patients), and household accidents (six patients). No significant differences in injury severity (Injury Severity Score mean values) were found among these four types of accidents: traffic: 22.2 (SD=10.4), sports or leisure: 23.6 (SD=12.2), workplace: 20.8 (SD=6.1), and household: 19.8 (SD=6.0) (F=0.31, df=3, 96, p=0.82). According to the surgeons’ files, 38 patients suffered from retrograde amnesia; 42 patients sustained a traumatic brain injury, i.e., they had objectively reported loss of consciousness and/or pathological findings on cranial computerized tomography. A significant association was found between retrograde amnesia and traumatic brain injury (Pearson χ

2=17.6, df=1, p<0.001).

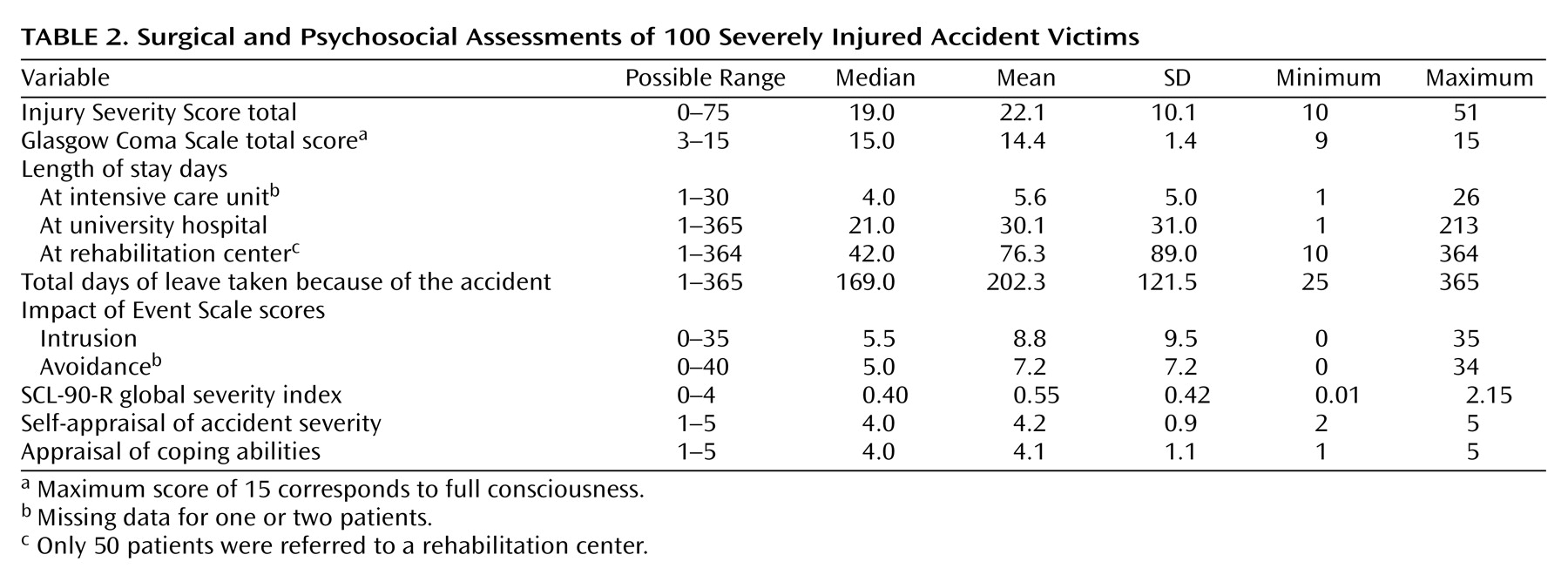

Initial assessments took place shortly after the patients had been transferred from the intensive care unit to the regular trauma surgeons’ ward. The mean number of days between the accident and interview was 13.5 (SD=6.6, range=3–29).

Measures

The Injury Severity Score

(13) permits an evaluation of the gravity of injuries by a trauma surgeon: every area of the body concerned is given a score (1=minimum, 6=fatal injury). The scores for the three most severely injured areas of the body are squared and then summed, producing a maximum score of 75. Patients with a score of 10 or more are generally considered severely injured. The Glasgow Coma Scale

(14) is an observer-rated scale for the clinical appraisal of the gravity of a coma after injury to the skull and brain. Patients with severe traumatic brain injuries generally have a score under 9.

In the semistructured interviews, sociodemographic data, including a detailed work record and information about the accidents were collected. The patients were asked to make a subjective appraisal of the severity of the accident by using a Likert scale, ranging from 1=very low to 5=very high. Furthermore, the patients were asked to assess their abilities to cope with the accident and its job-related consequences using a Likert scale, ranging from 1=very poor to 5=very good.

Posttraumatic psychological symptoms were assessed by using the Impact of Event Scale

(15), a 15-item self-rating questionnaire comprising two subscales (intrusion and avoidance) with high reliability and validity as a screening instrument for posttraumatic stress disorder

(16,

17). The SCL-90-R

(18,

19) was used to cover a broad range of psychopathological symptoms.

Time taken off work was calculated as the number of days of leave taken from the time of the injury (including time in the hospital), with a week off work equaling seven days of leave. When the subjects returned to work only part-time if they were previously full-time employees, the days on which they worked on a reduced level were added to the total days of leave on a prorated basis.

Predictive Model and Statistical Analyses

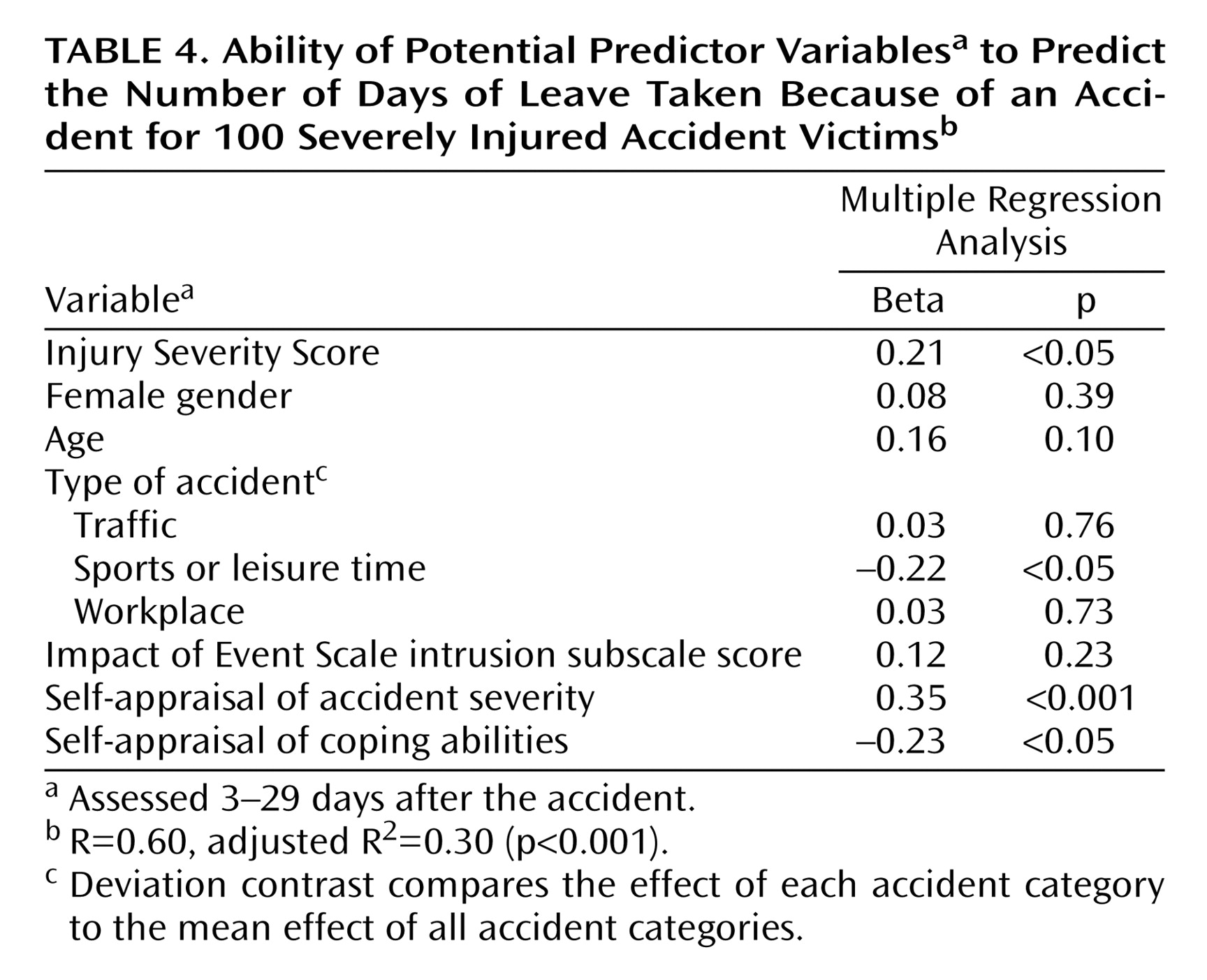

For the establishment of a stable regression model predicting the number of days of sick leave attributable to the accident, we selected nine potential predictor variables. In order to be suitable for the development of a screening instrument, all variables had to be assessed shortly after the accident and in a short time. Injury Severity scores and types of accident were chosen as objective accident-related variables. Gender and age were selected as potential pretraumatic predictors. The Impact of Event Scale intrusion subscale allows for a quick assessment of posttraumatic psychological symptoms (seven items regarding intrusive recollections of the trauma). The patients’ self-assessments were represented in the model by their subjective perception of accident severity and their appraisal of their ability to cope with the accident and its consequences.

Data were analyzed by using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

(20). Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to assess correlations between the target variable of leave taken from work because of the accident (assessed at the 12-month follow-up) and all potential predictor variables. Linear multiple regression analysis was used for the prediction of the total number of days of leave taken that were attributable to the accident during the first 12 months. To enter the type of accident (traffic, workplace, sports or leisure, or household) as a predictor into the multiple regression analysis, this categorical variable was converted into a set of three new variables so that a deviation contrast resulted. Accordingly, the effect of each accident category was compared to the mean effect of all accident categories. Since there was one new variable for each degree of freedom, one accident category (household) had to be omitted in the regression analysis

(21).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study that used a representative group of severely injured accident victims to investigate the determinants of the number of days of leave taken because of the accident. Our aim was to collect as homogeneous a group as possible, with patients free from mental disturbances that were attributable to severe head injuries. The mean Injury Severity Score (22.1) and the Glasgow Coma Scale score (14.4) in our group indicated that this goal was achieved. Furthermore, the patients were excluded from the study if they showed any signs of previous psychological problems. The exclusion of patients who had attempted suicide or had been exposed to a physical assault further contributed to the homogeneity of the group.

Contrary to other groups that were drawn from accident victims seeking treatment for their posttraumatic psychological problems

(22–

24) or claiming compensation for personal injury

(7), our group was collected consecutively, with the intensive care unit of the traumatology department of the University Hospital of Zurich as the single source. Only 10% of the eligible patients refused to participate in our study, an unusually low refusal rate compared with those in other published studies of accident victims

(25–

27). The dropout rate was also low. Comparative analyses of refusers and dropouts showed that our final group was representative of the population we intended to study. With regard to sociodemographic variables, our group was typical of groups of accident victims in general. Patients in this study were predominantly young men; marital status, living arrangements, educational level, and employment status corresponded to the sex and age distribution of admissions to our trauma surgeons’ intensive care unit. However, generalizability of our data to trauma populations with different socioeconomic and ethnic composition remains unclear.

This study has a number of limitations. First, the patients had to be excluded from the study if they did not speak German sufficiently. Proficiency in the official language of a country is a strong determinant of social integration; according to our clinical experience, patients with poor social integration have greater-than-average difficulties in dealing with the consequences of their accident. Therefore, in future studies, patients whose mother tongue is other than the country’s official language should be included by using interpreters. Second, the study did not include the full spectrum of accident victims, so inferences can only be made about those with severe accidental injuries. Also, certain types of injury are more likely to be related to unfitness for work, independent of the formal measure of the Injury Severity Score. For instance, patients with spinal cord injuries (Injury Severity Score=9) were not included in our study unless they had sustained additional injuries. Third, the patients’ self-assessments were not evaluated by using standardized instruments, but rather simple Likert scales. While the questions used have not been comprehensively validated, they certainly have face validity and their simplicity allows their use in routine clinical work. Furthermore, our results clearly support the predictive validity of the questions used. Finally, from our study design, one cannot be confident that the relationship between the attribution questions and outcome was a direct one, although this seems likely. Responses to these questions correlated with SCL-90-R scores (General Symptomatic Index by appraisal of accident severity [r=0.22, p<0.05] and by appraisal of coping abilities [r=–0.29, p<0.01]). As with other patient groups in the general hospital, a considerable proportion of our patients were likely to have been depressed, and depression in turn was likely to influence attributions

(28,

29). However, despite each self-assessment correlating with the General Symptomatic Index, they were independent of each other. If they were both manifestations of depression, surely this would not be the case. Also, patients’ reports may have been influenced by the recency of the traumatic event, pain medication, and sleep medication. Nevertheless, whether the attributions studied are directly relevant to outcome or represent epiphenomena of depression or other posttraumatic psychopathology, they appear to be markers of outcome which, because of their simplicity, are potentially useful clinically and for research.

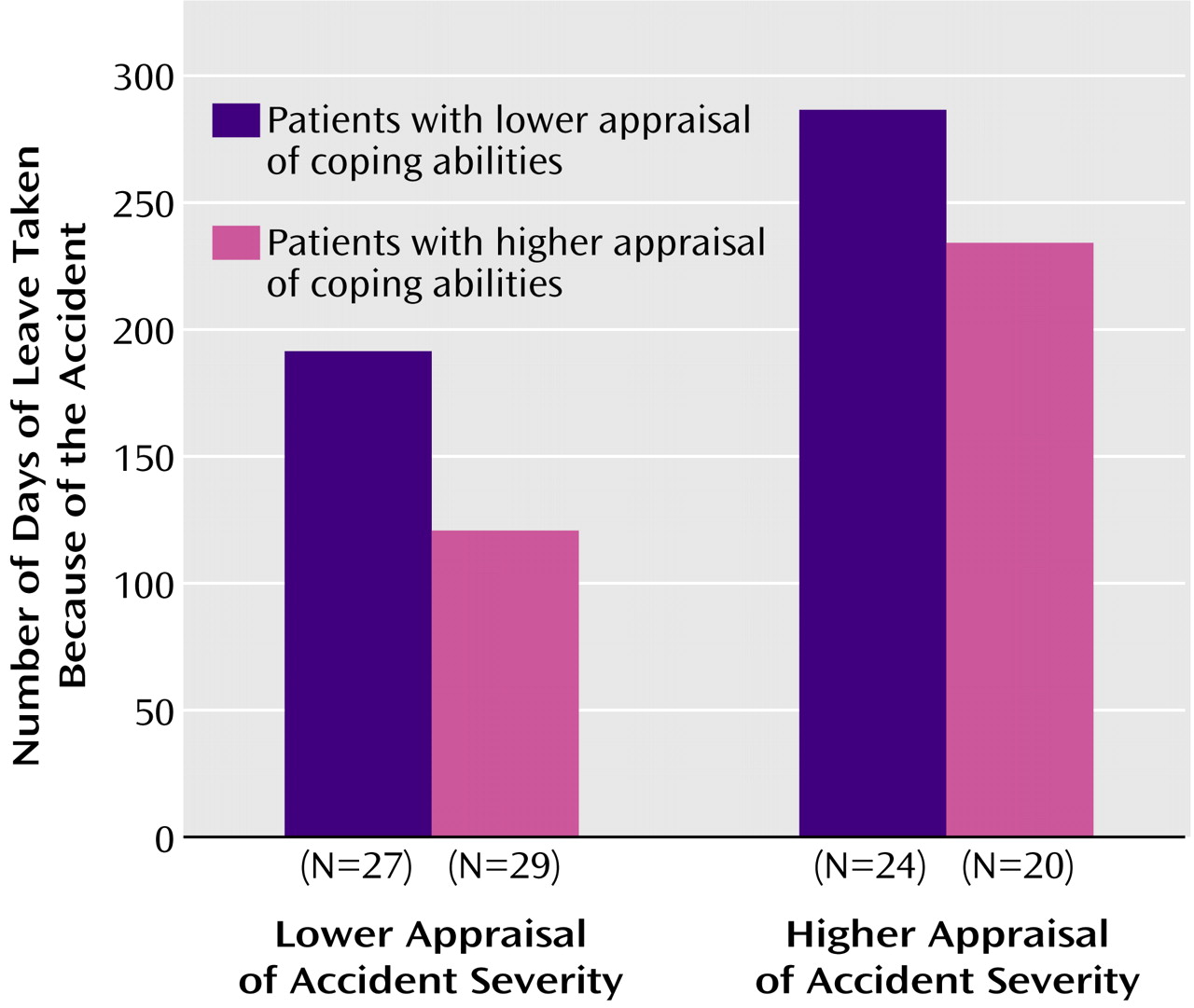

The key finding of this study was that patients’ appraisals of the severity of their accident and their ability to cope with the accident and its job-related consequences made substantial contributions to the duration of their time off work, independent of the severity of the injury. In addition, those who sustained their injuries during sports or leisure pursuits were likely to return to work sooner than those with injuries from other sorts of accidents, irrespective of the objective severity of the injuries.

The modest contribution of injury severity (assessed by the Injury Severity Score) to days of sick leave may have been due at least in part to the selection in this study of only patients with severe injuries. Had patients with mild or moderate injuries been included (thus covering the full range of Injury Severity Scores), the Injury Severity Score might have been a more powerful predictor of time taken off work. It is also noteworthy that, contrary to previous reports

(6,

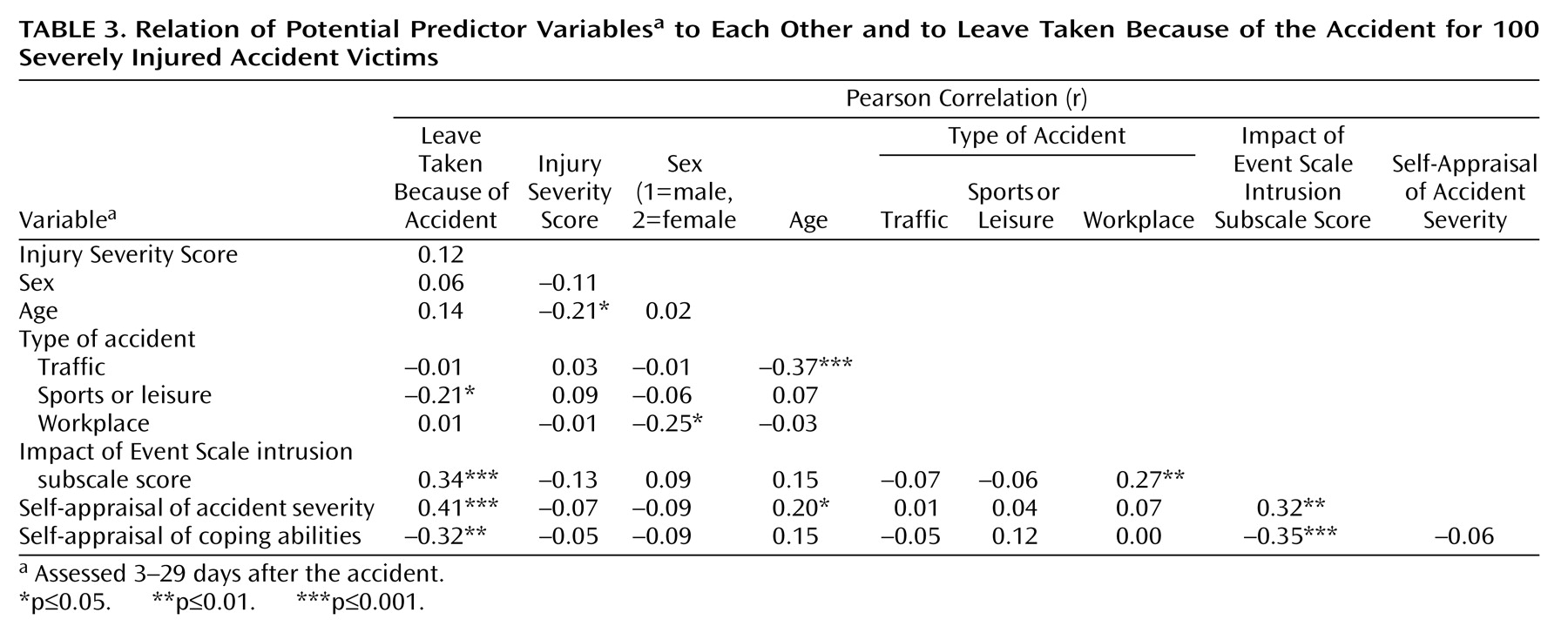

7), patients’ time taken off work was not independently predicted by their Impact of Event Scale scores. At the univariate level, Impact of Event Scale score correlated significantly with the number of days of leave taken; we assumed that in the multivariate analysis, the predictive power of the Impact of Event Scale score was suppressed by the patients’ appraisal variables, which each showed significant univariate correlations with Impact of Event Scale intrusion scores (

Table 3).

In the present study, the strongest predictors of time taken off work were the patients’ self-assessments of accident severity and of their ability to cope. That each of these was apparently independent of the objective severity of injury is consistent with other work on patient appraisal of illness

(28,

29). Cornes identified “psychological problems” as an important predictor of time taken off work because of accidental injuries

(7) but without specifying these psychological problems in greater detail. In another study, objective medical ratings of loss of earning capacity were reported not to be predictive of overall occupational or psychosocial adjustment

(30).

Patients who sustained their injuries during sports or leisure pursuits resumed work earlier than those whose accidents had other causes. To our knowledge, this finding has not been reported previously, although other authors have investigated samples of patients with different types of accidents

(31–

33). Several factors may contribute to this finding. First, patients in this group were more positive in their appraisals of their coping abilities than patients with other types of injury. Second, and possibly related to the first factor, people who have sustained injuries during activities that they freely choose to pursue are less likely to blame others for their accidents than those who were injured at work or in traffic accidents. It is possible that those injured during sports activities perceive such injuries as risks they choose to take, whereas work or traffic accidents are unlikely to be viewed in this light. Attributing blame to others has been associated in a variety of situations with unfavorable outcomes, although their influence on the outcome of accepting blame oneself has been less consistent

(28). Third, individuals who have been physically active might be expected to recover more rapidly than other people from their injuries, although the duration of hospitalization did not differ significantly across the types of accident.

The influence of patients’ self-assessments on the number of days of leave taken that were attributable to the accident was not just statistically significant but makes a remarkable difference from a clinical and economic perspective, too. While Injury Severity Scores did not differ significantly among the four subgroups formed based on patient self-assessments, time taken off work varied between 4 and 9 months (

Figure 1). Clearly, the results of this study could have numerous important clinical and therapeutic consequences, if they can be replicated in future work. First, attention to the cause of the trauma might assist in identifying subgroups of patients more likely than others to have longer time off work. Second, asking patients two brief and easily understandable questions may yield important information about key factors influencing the time to return to work. Third, our results suggest that an important focus for clinicians involved in the aftercare of patients with traumatic injuries should be to support and enhance their patients’ physical and psychological resources to cope with the accident and its sequelae. Finally, where a patient’s appraisals are pessimistic or negative, these are likely to be amenable to change. Under such circumstances, interventions might be helpful that aim to modify attributions, such as antidepressant treatment (if depression is present and is likely to have influenced the attributions) or cognitive behavior therapy. It has recently been reported that after myocardial infarction, therapeutically induced positive changes of illness perception were correlated with a faster return to work

(34). The preventive effect of such interventions in accident victims, given at an early stage of recovery, and particularly the extent to which they could reduce the time to return to work, will need to be examined in randomized controlled trials.