Practice guidelines and algorithms for schizophrenia recommend antipsychotic trial durations of at least three

(1,

2), four

(3–

5), or six

(6) weeks. This contrasts sharply with the current managed care environment, which often dictates a change of antipsychotic medication days after initiation in “nonresponsive” patients to facilitate their rapid discharge from inpatient settings. Unfortunately, there are few empirical data to support this practice

(7): few studies have critically examined the time course of symptom change following early treatment nonresponse.

Studies investigating diagnostic, clinical, biological, and pharmacological response predictors as well as the time-course of symptom change in schizophrenia have yielded inconsistent results, and methodological differences limit the interpretation of these data

(8). Given the unpredictable pretreatment discrimination of responders and nonresponders, investigation of variables during treatment may offer a more individualized prediction method. This is critical to 1) avoid unnecessary treatment of nonresponders, 2) avoid associated side effects, 3) ensure an adequate trial in subjects who are likely to benefit, 4) identify subjects early who may benefit from a different antipsychotic agent, 5) develop treatment algorithms, and 6) reduce illness burden and costs.

The few studies that have examined the correlation between short-term objective symptom changes and antipsychotic response reported positive results

(8–

14). However, interpretation of these studies is restricted by small sample sizes (26–72 subjects), exclusion of male

(11) or female

(8) patients, inclusion of >60% of haloperidol-unresponsive subjects (8), large variations in antipsychotic-free periods (3–60 days), nonstandardized treatment

(9,

12,

14), trial durations of as little as two

(9) or three

(12) weeks, employment of unusual loading strategies

(8,

13), and, most importantly, heterogeneous, nonoperationalized predictor and outcome variables

(8,

9,

11,

14). The aim of our study was to determine whether early reductions in psychotic symptoms would predict ultimate response status in a large group of uniformly treated patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder.

Method

One hundred thirty-one acutely ill inpatients 18 to 50 years of age with a DSM-III-R diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or schizophreniform disorder granted written informed consent to participate in a study of treatment strategies in schizophrenia

(15). These data are generated from the lead-in phase of this study, which was conducted in a nonselected group of patients with schizophrenia. Mean age of the subjects was 29.4 (SD=6.6), 62.6% were male, 46.9% were Caucasian, 38.3% were African American, 10.9% were Hispanic, and 3.9% were of other racial origin. Subjects were included if they were rated as moderate or worse on at least one of the four Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)

(16) psychotic symptom items (i.e., hallucinations, unusual thoughts, conceptual disorganization, or suspiciousness) after a drug washout period of at least 72 hours. Exclusion criteria were history of nonresponse to fluphenazine 20 mg/day or adequate doses of other neuroleptics, administration of a depot neuroleptic during the past 2 months, current substance abuse, and medical or psychiatric contraindications to neuroleptic treatment.

Each patient received open-label treatment with fluphenazine 10 mg twice daily plus benztropine 2 mg twice daily starting on day 1 of the study in a 4-week fixed-dose design. Symptom severity was assessed by trained raters with the 18-item BPRS at baseline and weekly thereafter.

Antipsychotic response was defined as a reduction of ≥20% in the total BPRS baseline score at 4 weeks. Predictor variables were a ≥20% reduction at 1 week in baseline BPRS total score and in the empirically derived factors for thought disturbance (hallucinations, unusual thoughts, conceptual disorganization), hostility-suspiciousness (hostility, suspiciousness, uncooperativeness), anxiety-depression (somatic concerns, anxiety, guilt feelings, depressed mood), and withdrawal-retardation (emotional withdrawal, psychomotor retardation, blunted affect)

(17).

To determine associations between symptom reductions and response status, chi-square tests were used. Logistic regression was carried out to determine whether baseline values were significant predictors when included in the defined models. In addition, sensitivity (correct prediction of responders), specificity (correct prediction of nonresponders), and predictive power (number of true positives plus number of true negatives divided by total number of patients) were calculated. Significance level was set at alpha=0.05, two-tailed. Data were analyzed with SAS, version 8.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.).

Results

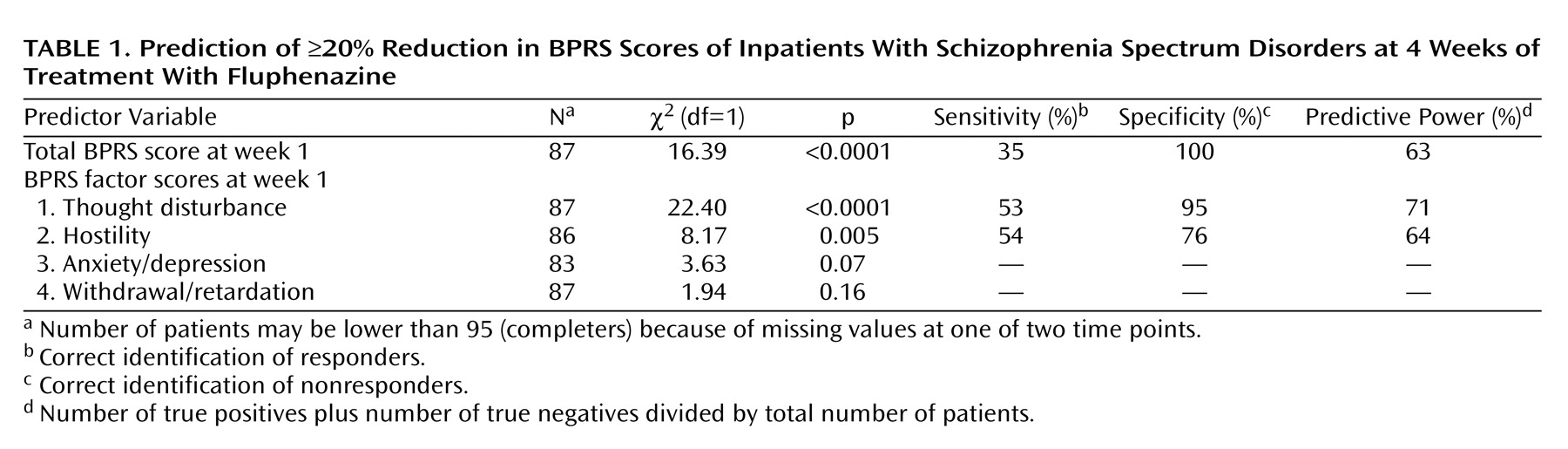

Ninety-five (72.5%) of the 131 patients completed the 4-week trial of conventional antipsychotics. Of these, 54 (56.8%) met response criteria. Responders and nonresponders did not differ in sex, age, and race. However, at baseline, responders had higher BPRS total scores (t=–3.18, df=92.9, p=0.002) as well as higher scores for thought disorder (t=–2.94, df=93, p=0.004) and hostility (t=–4.71, df=93, p<0.0001). Significant associations were found for response with ≥20% reductions in the total BPRS scores and thought disturbance and hostility scores at 1 week (

Table 1).

A <20% improvement in the total BPRS score or the thought disturbance factor at 1 week correctly predicted nonresponse at 4 weeks in 100% and 95% of patients, respectively. Conversely, ≥20% reductions in the total BPRS and thought disturbance and hostility factor scores at 1 week correctly identified response in only 35%, 53%, and 54%, respectively. Gender, age, and race were not significant predictors when added to the model.

Although baseline score was not a significant predictor when week 1 values were included in the model for the thought disturbance factor (likelihood ratio test χ2=28.02, df=2, 95, p<0.0001; baseline: Wald χ2=2.06, p=0.15; week 1: Wald χ2=13.52, p=0.0002), it was a significant predictor for the hostility factor (likelihood ratio test χ2=18.70, df=2, 95, p<0.0001; baseline: Wald χ2=8.31, p=0.004; week 1: Wald χ2=1.73, p=0.19). An adequate fit of the data could not be obtained for the BPRS total score with baseline and week 1 scores in the model.

Discussion

The main finding of this study is that all patients who displayed a <20% improvement in their BPRS total score and 95% of patients who displayed a <20% reduction in their BPRS thought disturbance factor score following 1 week of treatment with 20 mg/day of fluphenazine were correctly classified as nonresponders at the end of the study. Conversely, patients who did meet early response criteria did not necessarily maintain their response for the duration of the study; only 35% of patients with early reductions in BPRS total score ultimately met response criteria, and 53% of the patients with ≥20% reduction in the thought disturbance factor score ultimately met response criteria. These findings imply that early BPRS ratings may be useful to identify nonresponders as early as 7 days into treatment, providing the basis for changing antipsychotic treatment.

These results are consistent with those of previous studies finding significant associations between varying outcome definitions and early symptom improvements in response to treatment according to a wide variety of symptom measures

(8–

14), including BPRS total

(8,

11,

12) and factor

(13,

14) scores. The time point of 1 week for predictive psychopathology assessments corresponds with that used in some studies

(9–

12), although in others symptom changes as early as five

(12), three

(8,

9), or even two

(13,

14) days predicted outcome.

Strengths of this study include the rigorous diagnostic criteria, representative patient group, fixed-dose design, use of operationalized predictor and outcome variables, and a two to four times larger study group than in previous trials. Limitations include the nonblinded design, yet all patients received the same fixed-dose treatment. The relatively high dose of fluphenazine is another limitation, because presence of akathisia or extrapyramidal symptoms could have been interpreted as poor symptom response, despite the fact that all patients received prophylactic treatment with benztropine 4 mg/day

(18).

Furthermore, since symptoms were rated weekly, we cannot exclude that symptom improvement before day 7 of antipsychotic treatment may be as reliable or even more reliable as a predictor than improvement at 1 week. Moreover, the trial duration of 4 weeks leaves the possibility that some patients may have responded had the trial lasted longer, although the response rates in studies that have lasted five

(8), six

(10), and eight

(15) weeks were lower than ours, albeit with different response criteria.

Finally, as with all previous studies, patients received a first-generation antipsychotic, limiting the generalizability of the findings to second-generation antipsychotics. However, despite improved effectiveness of second-generation antipsychotics

(19), there is no evidence that response patterns would differ significantly from those of conventional neuroleptics.

Although seemingly tautological (i.e., “nonresponse predicts nonresponse”), our results provide further preliminary evidence that 1) relevant antipsychotic efficacy is unlikely to occur if it does not begin in the first week of treatment and 2) objective symptom ratings may be a clinically useful, time-effective, and cost-effective method to guide early antipsychotic treatment decisions. Further studies, preferably involving second-generation antipsychotics, larger patient groups, frequent early symptom ratings, and longer duration than 4 weeks, are needed to better determine the predictive value of initial symptom reductions for ultimate treatment response.