The epidemiology of anxiety and mood disorders, in adults as well as in adolescents, has been studied over the past two decades by using standardized diagnostic instruments such as the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule

(1) or the Composite International Diagnostic Interview

(2). These studies (for example, those described in references

3–6) have shown that anxiety and mood disorders are frequently occurring psychiatric disorders, with lifetime prevalences between 19% and 28%. Both disorders are much more frequent in females than in males.

In recent years, more attention has been paid to the distributions of the ages at onset of the different disorders. Anxiety disorders predominately start in childhood or early adolescence, whereas depressive disorders are associated with increasing incidences in late adolescence and early adulthood

(7). These distributions are similar in males and females. However, the causes for these different onsets are unknown. Finding predictors of the age at onset of mood and anxiety disorders would be an important step in unraveling these causes.

Several researchers have described associations between emotional and behavioral problems in childhood and psychiatric disorders in adulthood. Behaviorally inhibited children are more likely to meet diagnostic criteria for depression in adulthood, according to data adjusted for gender

(7,

8). Rule-breaking behavior in childhood predicts adult anxiety disorders in women and mood disorders in men

(9). The associations found in these studies were presented as odds ratios, reflecting the presence of significant associations between childhood behavior and adult psychiatric disorders. To address questions about whether and, particularly, when mood and anxiety disorders develop, other statistical techniques are needed

(10).

Our study concerns a 14-year follow-up of parent-reported behavioral and emotional problems, determined in 1983 with the Child Behavior Checklist

(11), in subjects randomly selected from the Dutch general population, initially 4–16 years of age. In 1997, mood and anxiety diagnoses were retrospectively obtained with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. The main aims of the present study were 1) to examine temporal patterns in the onset of mood and anxiety disorders, 2) to predict the onset of mood and anxiety disorders from parent-reported emotional and behavioral problems across a 14-year period during adolescence and young adulthood, 3) to evaluate the stability and change of the strength of the prediction across time, and 4) to test whether gender, age at initial assessment, and socioeconomic status are related to the likelihood of developing mood and anxiety disorders, after the problem behavior is accounted for, and whether these relationships change across time.

Results

Temporal Patterns

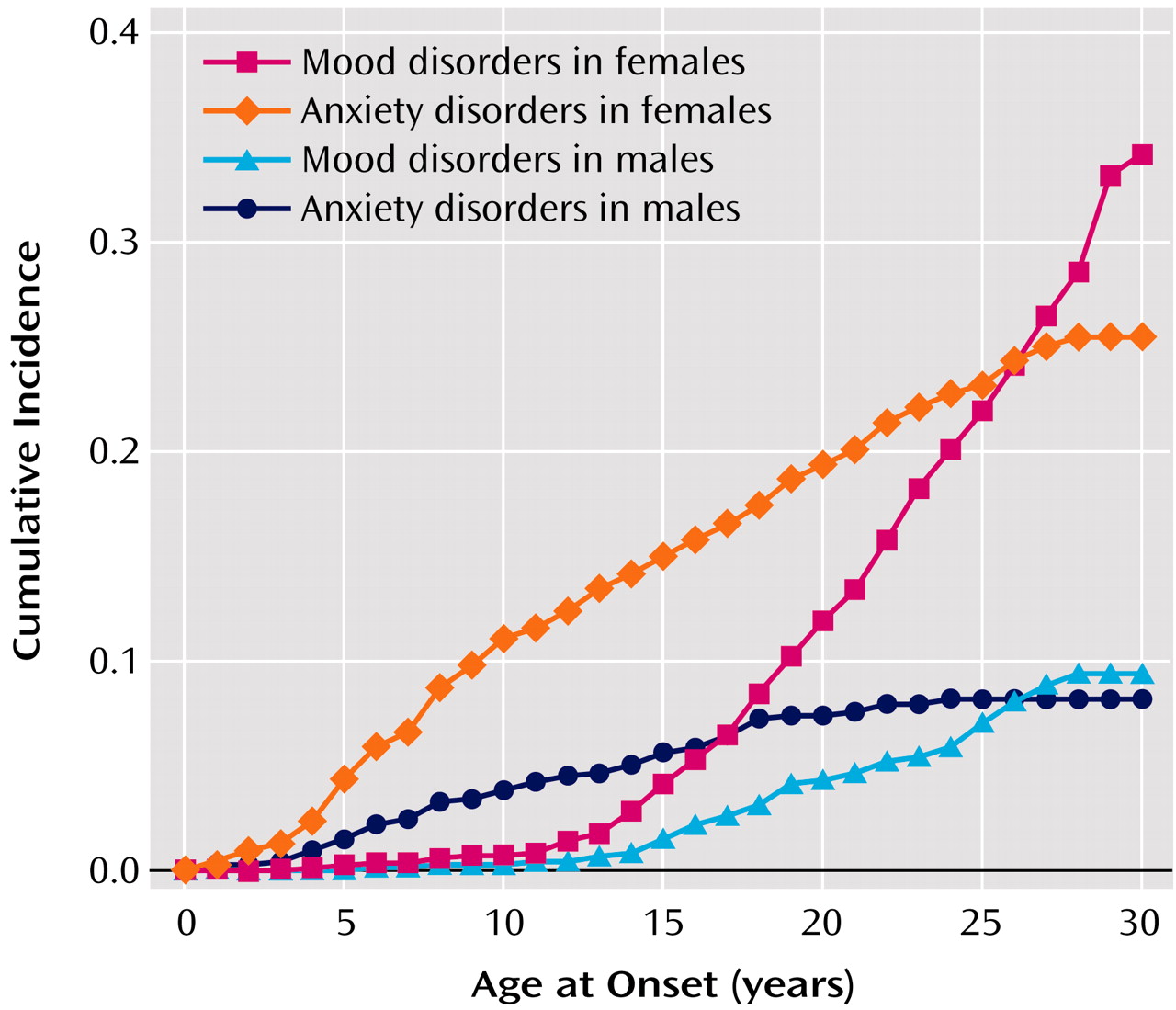

Figure 1 shows the cumulative incidence of anxiety and mood disorders by age at onset for each gender separately. Cumulative incidence is the number of subjects developing a disorder during a certain time period divided by the total number of subjects followed for that period. The risk for onset of mood disorder sharply rose approximately beginning at age 13, with a steady increase up to age 30. While the difference in risk between men and women was small in childhood up to the age of 12 years, in adolescence and young adulthood the risk difference between the two genders became larger.

Anxiety disorders were more frequent than mood disorders until the age of 25, both in males and females. After the age of 25, the cumulative incidence of anxiety disorders did not increase anymore, in contrast to the cumulative incidence of mood disorders.

For individuals who developed both mood and anxiety disorders during their lifetimes, the anxiety disorder started before the mood disorder in most cases (68.8%, 64 of 93). These 64 represent 27.6% of the 232 subjects with mood disorders. Only 10.8% (N=10) of the 93 subjects with both disorders developed the mood disorder before the anxiety disorder. The time between the onsets of the two disorders was significantly longer for the subjects who developed the anxiety disorder first; the mean for this group was 9.2 years, and the 95% confidence interval (CI) was 7.8–10.6, whereas for those whose mood disorder was diagnosed first, the mean was 2.2 years (95% CI=1.1–3.3). In 19 subjects (20.4%), the anxiety disorder and the mood disorder started within the same year.

Of the 232 subjects with mood disorders, major depressive disorder was the most frequent diagnosis (92.7%, N=215). The other mood disorders were less common; bipolar disorder was diagnosed in 5.2% (N=12), and dysthymia was diagnosed in 2.6% (N=6). Among the 250 subjects with anxiety disorders, the most frequent diagnoses were specific phobia (57.6%, N=144), posttraumatic stress disorder (18.8%, N=47), and social phobia (12.8%, N=32).

Predictors of Mood Disorders

Of the 1,580 subjects for whom the Child Behavior Checklist was completed at initial assessment and a psychiatric interview was completed at follow-up, eight (0.5%) subjects claimed to have complaints of mood disorder at the initial assessment and were excluded from the analyses to ensure that only new cases were considered in our analyses. The remaining 1,572 subjects formed the initial group “at risk.”

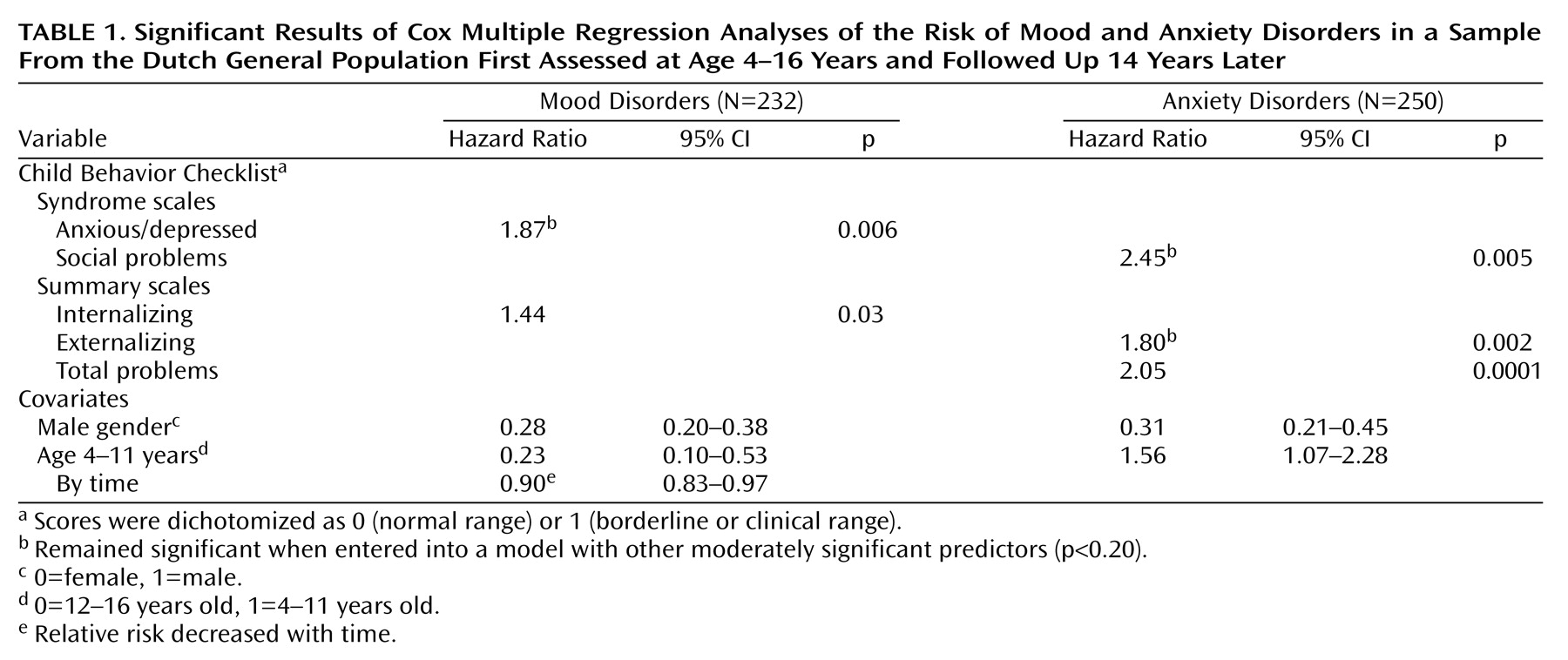

The statistically significant estimates of the relative risk of mood disorders obtained from the Cox multiple regression analyses are given in

Table 1 (left side). First, we tested eight models, all including one Child Behavior Checklist syndrome along with the covariates common to all models, i.e., gender and age. To correct for multiple comparisons, we used the Bonferroni method to adjust the p values. The p value obtained from each of the eight tests was multiplied by 8. When the corrected p value was smaller than 0.05, the scale was a significant predictor. Anxious/depressed was the only syndrome that significantly predicted mood disorders. In the multivariate model, containing all moderately significant determinants (p<0.20), only anxious/depressed remained significant, indicating that this scale predicted the onset of mood disorders independent of the other Child Behavior Checklist scales. Adding the interaction with time to the model did not improve the model fit significantly.

The same procedure was applied to the broad scales for internalizing and externalizing. First, we adjusted each scale separately for the covariates age and gender. The p value obtained from each of these two tests was multiplied by 2 to correct for multiple comparisons. These analyses yielded a relative risk that was significant only for the internalizing scale. When both internalizing and externalizing (both moderately significant predictors of mood disorder, with p<0.20) were included in one model, internalizing was not significant anymore, indicating that internalizing behavior did not predict the incidence of mood disorders independent of the prediction of externalizing behavior.

Gender and age significantly predicted mood disorders. Males were less likely to have a mood disorder in the follow-up period than females. Younger children (4–11 years of age) were less likely to have a mood disorder than older children (12–16 years), but the relative risk decreased with the length of follow-up. Socioeconomic status was not related to the onset of mood disorders.

There were no significant interactions between the problem scales and the demographic covariates, i.e., the associations between problem behavior and mood disorders were similar for males and females, for ages 4–11 and 12–16 years, and for the two levels of socioeconomic status.

Results regarding the covariates age and gender were similar across the models.

Table 1 shows the estimates of age and gender in the multivariate analysis.

Predictors of Anxiety Disorders

Of the 1,580 subjects, 106 (6.7%) claimed to have complaints of anxiety disorder at the initial assessment and were excluded from the analyses to ensure that only new cases were considered. The remaining 1,474 subjects formed the initial group “at risk.”

The significant estimates of the relative risk of anxiety disorders obtained from the Cox multiple regression analyses are given in

Table 1 (right side). Again, we tested eight models, each including one Child Behavior Checklist syndrome along with the covariates common to all models, i.e., gender and age. The p values were multiplied by 8 to correct for multiple comparisons. Only social problems was significant, indicating that only this syndrome had a significant relationship with the incidence of anxiety disorders independent of the other syndromes. Adding the interaction with time did not significantly improve the model fit.

When adjusted for age and gender, the externalizing scale was a significant predictor of the incidence of anxiety disorders. Externalizing also predicted the onset of anxiety disorders independent of internalizing behavior.

Gender and age significantly predicted anxiety disorders. Males were less likely to have an anxiety disorder in the 14-year follow-up. Children ages 4–11 years were more likely to have an anxiety disorder in the next 14 years than older children (12–16 years).

There were no significant interactions between the scales for problem behavior and the covariates age, gender, and socioeconomic status.

Results regarding the covariates age and gender were similar across the models. Socioeconomic status was excluded from the multiple models because its contribution to the prediction was not significant.

Discussion

The present study showed that emotional and behavioral problems reported by parents in childhood or adolescence on the Child Behavior Checklist predicted the onset of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders across a 14-year period. None of the predictions based on problem behavior significantly changed across the follow-up time. Gender and age at initial assessment were significantly associated with the onset of mood and anxiety disorders. The relationship between age at initial assessment and the onset of mood disorders significantly changed across time. The subjects who were adolescents (12–16 years) at the initial assessment were more likely to have mood disorders than younger children (4–11 years). With longer follow-up time, when the subjects who were young children at the initial assessment grew up into teenagers, the relative risk decreased.

Like findings in other studies

(5–

7), our results showed that anxiety disorders predominantly started in childhood and early adolescence, whereas the incidence of depressive disorder increased sharply in adolescence and young adulthood. Both anxiety and mood disorders were more frequent in females than in males. In most individuals diagnosed with both anxiety and depressive disorders, the anxiety disorder started before the mood disorder.

Predictors of Mood Disorders

Mood disorders were significantly predicted by scores on the anxious/depressed scale of the Child Behavior Checklist. The broad internalizing scale, consisting of the withdrawn, somatic complaints, and anxious/depressed syndromes, predicted the onset of mood disorders but not independent of the score on the externalizing scale. Earlier reports showed findings similar to ours in that inhibited children were more likely to be diagnosed with mood disorders in adolescence and young adulthood

(6,

8). However, some found this association to occur only in males

(9), whereas others did not find significant interactions with sex

(8). As in the current study, both males and females experienced higher risk for depression if they were anxious or depressed in childhood. It has been hypothesized

(20) that anxious or inhibited temperament can increase stress reactivity. Especially in girls, the transition from childhood into adulthood during adolescence, with the physical changes related to pubertal development and the intensification of stereotypical gender roles, is experienced in a negative way

(21). Our results show that both boys and girls with problems reflecting inhibited temperament are more vulnerable to later depression. However, girls are more likely to develop a depressive disorder, possibly because they experience more stress during the adolescent transition.

The strength of the prediction based on problem behavior showed stability across time, indicating that children who are anxious/depressed have a higher risk across the whole pubertal period and young adulthood than do “normal” children without emotional or behavioral problems, even 14 years after initial assessment.

Predictors of Anxiety Disorders

Scores for social problems significantly predicted anxiety disorders. Externalizing behavior significantly predicted the onset of anxiety disorders, independent of the internalizing score. Earlier reports showed these associations only in females

(9), while our results were not conditioned by sex. Although the social problems scale, comprising items such as “acts too young for age,” “too dependent,” “does not get along with other kids,” “gets teased a lot,” “not liked by other kids,” “poorly coordinated or clumsy,” and “prefers being with younger kids,” does not seem to have a clear counterpart in DSM-IV

(22), our results showed a strong association between this scale and later anxiety disorders. A study among schoolchildren in the United Kingdom

(23) demonstrated an association between being bullied at school and a high anxiety score based on self-reports. The downward spiral starting with poor social skills and difficulties in peer relationships, which can lead to low self-confidence, negative self-evaluation, and self-criticism, leading to even more difficulties in peer relationships, up to being bullied and teased, can result in specific anxiety symptoms such as perceived danger and threat, uncertainty, and hypervigilance.

As reflected in the stability of the predictions found in the present study, the association between social problems and anxiety disorders does not decrease across time.

Limitations

The strengths of this study are its long follow-up period, spanning 14 years through adolescence and young adulthood, and its sample size, which was large enough to examine relatively common psychiatric disorders, such as major depressive disorder and several anxiety disorders. However, some potential methodological limitations need to be considered. As in other longitudinal studies, the generalizability is questionable because of sample attrition, despite the facts that we traced 79.0% of the time 1 sample and that our data did not suggest selective attrition. Second, the retrospective diagnoses of mood and anxiety disorders based on patients’ reports of when they first experienced complaints of the disorders could have introduced recall error. People tend to underestimate past morbidity, which may lead to significant underestimation of the lifetime prevalences reported

(24). Furthermore, respondents may “telescope” time and shift the age at first onset toward recent years, which would lead to overestimation of disease incidence during the period immediately before assessment with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. This could explain the fact that we did not find significant changes in the predictions of mood and anxiety disorders across time. Because stability of recall is also related to receipt of treatment and because interventions could have influenced the course of problem behaviors from childhood into adulthood, a third limitation of the current study is the fact that we did not include standardized information on treatment during the follow-up period.

Conclusions and Implications

Despite the fact that almost 28% of the mood disorders were preceded by an anxiety disorder, our results suggest different developmental pathways for anxiety and mood disorders. Mood disorders in adulthood are generally predicted by parent-reported internalizing behavior, while anxiety disorders are predicted by parent-reported social problems and externalizing behavior in childhood. These predictions based on parent-reported problem behavior were not liable to recall biases. Supplementary to the discussion of whether anxiety and mood disorders are distinct psychiatric disorders, our results suggest that the two disorders have diverse roots in childhood. Speculations about a common pathophysiological mechanism for anxiety and depression

(25) are therefore not supported by our results.

Gender differences were lacking in the predictions, indicating that the higher frequencies of both anxiety and mood disorders among females are due to factors other than problem behavior in childhood, such as environmental factors in adolescence or genes that come into expression later in life.

Even more striking about our results is the stability of the predictions during a 14-year period across adolescence and young adulthood.

Therefore, our results have several clinical implications, both for mental health professionals working with children and adolescents and for adult psychiatrists. The long-term consequences of problem behavior and emotional problems in childhood for later adult functioning support the importance of early intervention and prevention of such problems in young children. Parental reports are the most commonly used approach in studies of children ages 12 and under. Also, in the clinical evaluation of young children, parent reports might contribute to treatment planning and prognostic statements. For young children with externalizing behavior, the focus should be not only the disruptive aspects of their psychopathology but also their inner life and emotional needs. Moreover, the information on childhood origins of adult psychopathology adds to the general understanding of psychiatric disorders and may contribute to advances in diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis in adult psychiatry.

Nonetheless, the overlap between anxiety and depressive symptoms, both within episodes and over a lifetime, remains unclear. At the same time, little is known about the developmental route of social problems into anxiety disorder. Further research is needed to understand the causal pathways of specific childhood behavior through anxiety disorders into major depressive disorder.