Although schizophrenia is a major mental illness that can be treated, primary prevention of this disorder has been elusive. Nevertheless, a population-based strategy for preventing this debilitating mental disorder may not so much involve addressing the end-state of the disease process as it would involve developing primary prevention programs that tackle the milder, prodromal, prepsychotic features of the disorder, which have much in common with the features of DSM-IV schizotypal personality disorder (e.g., unusual perceptual experiences, no close friends, cognitive disorganization)

(1). If primary prevention programs could be developed to attenuate individual differences in schizotypal features in the general population, such efforts could provide the basis for developing new programs aimed at preventing schizophrenia

(2). To our knowledge, no such primary prevention programs have been developed for either schizophrenia or schizotypal personality

(3).

International epidemiological studies have shown higher rates of criminal offending in schizophrenia patients, compared with the general population

(4–

8). A number of the neurobiological and psychological risk factors for schizophrenia are also risk factors for crime

(5,

6). Consequently, primary prevention efforts for schizotypy and schizophrenia may also reduce rates of conduct disorder and criminal behavior. Violence and crime are increasingly being viewed as major public health problems with origins in the early years of life

(9–

11), and prevention of these behaviors is one of the most important and pressing issues in society today. Yet, very few primary prevention studies have examined interventions in the early years of life to tackle the root causes of conduct disorder. Because animal research has clearly shown that environmental enrichment benefits both brain structure and function

(12–

14), and because brain imaging and neuropsychological studies have provided evidence of brain dysfunction in both schizophrenia and antisocial behavior

(15–

22), it is conceivable that early environmental enrichment could reduce both schizotypal personality and antisocial behavior.

Nutrition may be an important component of early environmental enrichment. Nutritional deficits have been implicated both in antisocial personality and in schizophrenia and schizoid personality

(23–

25), and animal experimental studies have demonstrated the importance of nutrition in cognitive and brain functioning

(26,

27). One of most successful early interventions for antisocial behavior to date involved home visits by nurses to mothers in which nutritional advice was a major component

(28). Consequently, an enrichment program that provides better early nutrition could reduce schizotypal personality and antisocial behavior, especially in subjects with poor nutritional status at the start of the prevention program.

The goal of this study was to assess the effects of early environmental enrichment, including a nutritional component, from ages 3 to 5 years on later antisocial behavior and schizotypal personality

(29). The study also assessed whether any beneficial effects were maximized in children with poor nutrition. Because this program had already been shown to produce long-term changes in psychophysiological functioning 8 years after the intervention

(30), the potential moderating effect of psychophysiological functioning on the effects of the enrichment program was also assessed.

Method

Subjects

Subjects were drawn from a larger population of 1,795 children from Mauritius and are described in full elsewhere

(30,

31). All children born in 1969–1970 in two towns were recruited into the study at age 3 years. This total sample consisted of both male (51.4%) and female (48.6%) children. Ethnic distribution was as follows: Indian, 68.7%; Creoles, 25.7%; and others, 5.6%. After complete description of the study to the subjects, verbal informed consent was obtained from the mothers of the participants for the study phase when subjects were ages 3–5 years, and written informed consent was obtained from the subjects for later study phases. Early research activities were conducted according to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki

(32), while research activities in later years were conducted by using the principles outlined in the Belmont Report

(33). Institutional review board approval for the later research phases was obtained from the University of Southern California.

Stratified random sampling was conducted by using random-number tables to select 100 children from the larger population of 1,795 to enter the enrichment program. The remaining 1,695 children experienced the normal community (control) condition. The 100 children entering the enrichment program were grouped according to measures of autonomic functioning to assess the moderating effects of autonomic activity on the enrichment (see reference

31 and a subsequent paragraph in the Method section for further details). The control subjects were selected from the remaining 1,695 children to match the enrichment group on autonomic functioning as well as other key age-3 variables that could influence outcome. Of the original 100 children in the enrichment group, 83 provided follow-up outcome data. This enrichment group was matched on 10 age-3 variables (ethnicity, gender, age, nutritional status, cognitive ability, temperament, autonomic reactivity, parental social class, social adversity, and mother’s age at birth) with 355 control subjects for whom outcome data were available. The characteristics of the two groups are summarized in

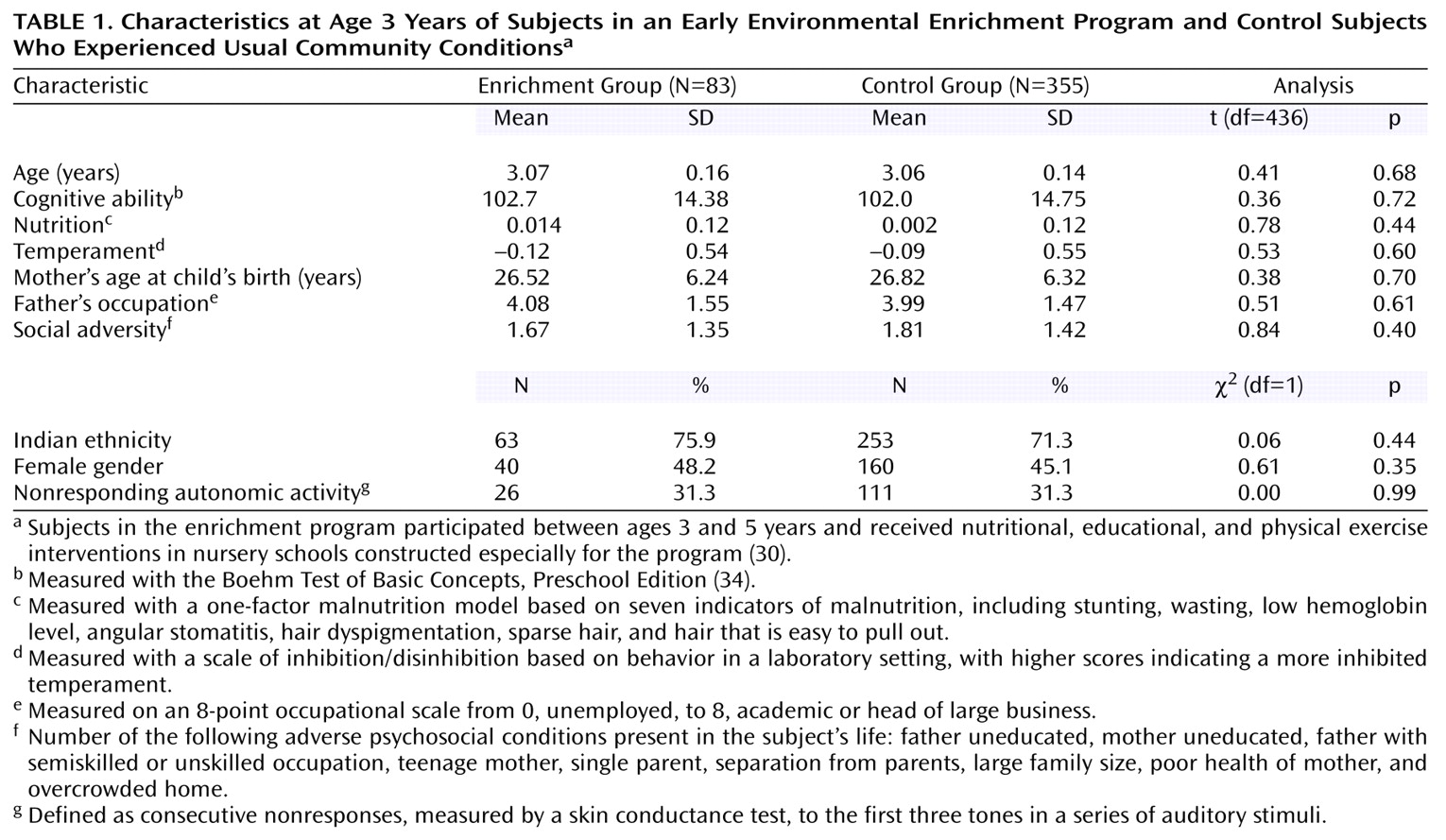

Table 1. No significant between-group differences were found (all p values >0.35), which shows close matching between groups.

At age 17, a total of 438 participants (including 83 participants in the enrichment group) had complete data on behavior problems. Among these 438 participants, there were no differences between the enrichment group and the control group in age (t=0.41, df=436, p=0.68), ethnicity (χ2=0.06, df=1, p=0.44), or gender (χ2=0.61, df=1, p=0.35). At age 17, a total of 339 participants (including 74 in the enrichment group) had complete data on schizotypy. Among these 339 participants, there were no differences between the enrichment group and the control group in age (t=0.54, df=337, p=0.58), ethnicity (χ2=0.33, df=1, p=0.57), or gender (χ2=0.56, df=1, p=0.46).

At ages 23–26, a total of 359 participants (including 75 in the enrichment group) had complete data on schizotypy. Among these 359 participants, the enrichment group did not differ from the control group in age (t=0.46, df=357, p=0.65), ethnicity (χ2=0.52, df=1, p=0.47), or gender (χ2=1.90, df=1, p=0.16). Among the 438 participants (83 in the enrichment group) who had complete data from court records on criminal activity, there were no differences between the enrichment group and the control group in age (t=0.41, df=436, p=0.68), ethnicity (χ2=0.06, df=1, p=0.44), or gender (χ2=0.61, df=1, p=0.35). Among the 360 participants (72 in the enrichment group) with complete data on self-reported crime, the enrichment group and the control group did not differ significantly in age (t=0.43, df=358, p=0.67), ethnicity (χ2=0.42, df=1, p=0.51), or gender (χ2=2.07, df=1, p=0.15). The participants included in these analyses (N=438) did not differ significantly from the remainder of the population (N=1,357) in age (t=0.50, df=1,793, p=0.62), ethnicity (χ2=0.19, df=1, p=0.66), or gender (χ2=1.48, df=1, p=0.22).

Enrichment and Community Control Conditions

The enrichment and control conditions have been fully described elsewhere

(30). Briefly, the enrichment program started at age 3 years, lasted 2 years, and consisted of three key elements: nutrition, education, and physical exercise. The enrichment program was conducted in two specially constructed nursery schools that had a teacher-pupil ratio of 1:5.5. A special feature of the nurseries was the emphasis on nutrition, health care, basic hygiene, and exercise

(31). Staff had training in physical health (nutrition, hygiene, anatomy and physiology, childhood disorders), physical activities (gymnastics and rhythm activities, outdoor activities, physiotherapy), and education (multimodal stimulation, use of toys, art, handicrafts, drama, music). A structured nutrition program provided the children with milk, fruit juice, a hot meal of fish or chicken or mutton, and a salad each day. A program of physical exercise consisting of gymnastics lessons, structured outdoor games, and free play was incorporated into the afternoon session of each day. The enrichment program also included walking, field trips, instruction in basic hygiene skills, and medical inspections (every 2 months)

(30). An average of 2.5 hours of physical activities occurred each day. Educational activities focused on verbal skills, visuospatial coordination, conceptual skills, memory, and sensation and perception.

The children in the control condition underwent the traditional Mauritius community experience, which consisted of attendance at “petite ecoles”

(30). These schools had a traditional grade-school curriculum and a teacher-pupil ratio of 1:30. No lunch, milk, or structured exercise was provided. For lunch, children typically ate bread only, rice and bread, or rice only.

Autonomic Functioning at Age 3 Years

Full details of the autonomic measures are given elsewhere

(30,

31). Briefly, subjects were presented with a series of auditory tone stimuli while skin conductance was recorded from bipolar leads on the medial phalanges of the first and second fingers of the left hand by using a constant voltage system. Beckman miniature Ag/AgCl type (4-mm diameter) electrodes were filled with 0.5% KCl in 2% agar-agar as the electrolyte. Responses >0.05 microsiemens occurring within a 1–3-second poststimulus window were scored. Nonresponding was defined as giving three consecutive nonresponses to the first three tone stimuli.

Demographic and Psychosocial Measures at Age 3 Years

When the children included in the study were age 3 years, a social worker visited the homes of the subjects’ parents and collected demographic and psychosocial information

(35). A total adversity score

(35,

36) was created by adding 1 point for each of the following nine variables: father uneducated (no schooling; present for 30.0% of the subjects), mother uneducated (no schooling; present for 29.4% of the subjects), father with semiskilled or unskilled occupation (occupational status of 3 or less on an 8-point occupational scale: 0=unemployed, 4=factory worker, cook, 8=academic, head of large business; present for 55.5%), teenage mother (age 19 or younger when child was born; present for 14.2%), single parent (present for 2.1%), separation from parents (orphaned or raised by substitute mother; present for 0.9%), large family size (sibling order fifth or higher by age 3 years; present for 30.0%), poor health of mother (coded 1 on a 3-point scale: above average=3, average=2, below average=1; present for 3.3%), and overcrowded home (five or more family members/house room; present for 28.8%). Scores ranged from 0 to 7 (mean=1.93, SD=1.39). Subjects with two or more indicators were defined as having psychosocial adversity.

Malnutrition at Age 3 Years

Seven indicators of malnutrition were assessed in an examination conducted by a pediatrician when the child was age 3 years. The indicators were stunting (reduced height for age), based on the standing height of the child and expressed as observed height as a percentage of expected height for the child’s age, with expected height based on Mauritian norms from the entire birth cohort; wasting (reduced weight for height), based on the weight of the child in light clothes without shoes and expressed as the ratio of observed weight to expected weight based on Mauritian norms of expected weight for height; hemoglobin levels, assessed from blood samples taken from the child; angular stomatitis (cracking in the lips and corners of the mouth), which predominantly reflects riboflavin deficiency (vitamin B

2) but also reflects niacin deficiency

(37); hair dyspigmentation (e.g., red hair, a sign of kwashiorkor), reflecting protein malnutrition and zinc and copper deficiency

(38); sparse, thin hair, a sign of protein-energy, zinc, and iron deficiency

(39) as well as a sign of general malnutrition; and hair that is easy to pull out, reflecting protein-energy deficiency

(40). A confirmatory factor analysis (conducted with EQS structural equation modeling software [Multivariate Software, Encino, Calif.]) of these seven variables established a one-factor (malnutrition) model with significant fit indices of 0.99 for the goodness of fit index, 0.98 for the adjusted goodness of fit index, and 0.05 for the root-mean-square error of approximation. A median split on standardized factor scores was used to designate subjects as either malnourished or nonmalnourished.

Behavioral Outcome Measures

Age 17 years

Schizotypal personality was assessed by using a self-report questionnaire that yielded two indicators of schizotypal personality: positive schizotypal personality (including unusual perceptual experiences and magical thinking)

(41,

42) and cognitive disorganization

(43). Details on the reliability and validity of this measure have been reported elsewhere

(41,

42).

Ratings of behavior problems were obtained by using the Revised Behavior Problem Checklist

(44). This instrument assesses six dimensions of behavior problems: conduct disorder, motor excess, attention problems, psychotic behavior, anxiety-withdrawal, and socialized aggression. Details on the reliability and validity of this instrument have been provided elsewhere

(44).

Age 23 years

Schizotypal personality was assessed by using the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire

(45). Full details on the reliability and validity of this instrument have been provided elsewhere

(36,

45). This instrument yields a total score and scores for three subfactors measuring cognitive-perceptual, interpersonal deficits, and disorganized features

(46).

Subjects were interviewed about their histories of criminal offending by using a structured interview consisting of an adult extension of the self-report delinquency measure from the National Youth Survey

(47). This instrument queries respondents about the perpetration of 41 criminal offenses that cover a wide range of property, drug, violent, and white-collar crimes over the past 5 years. The 33.6% of subjects who admitted to a criminal offense were categorized as offenders. The internal reliability (coefficient alpha) for the scale was 0.84. In addition, court records were searched for registrations of offenses that included property, drug, violence, and serious driving offenses (e.g., driving while drunk, dangerous driving) but excluded petty offenses (e.g., parking fines, lack of vehicle registration). Subjects with such a court record were categorized as criminal.

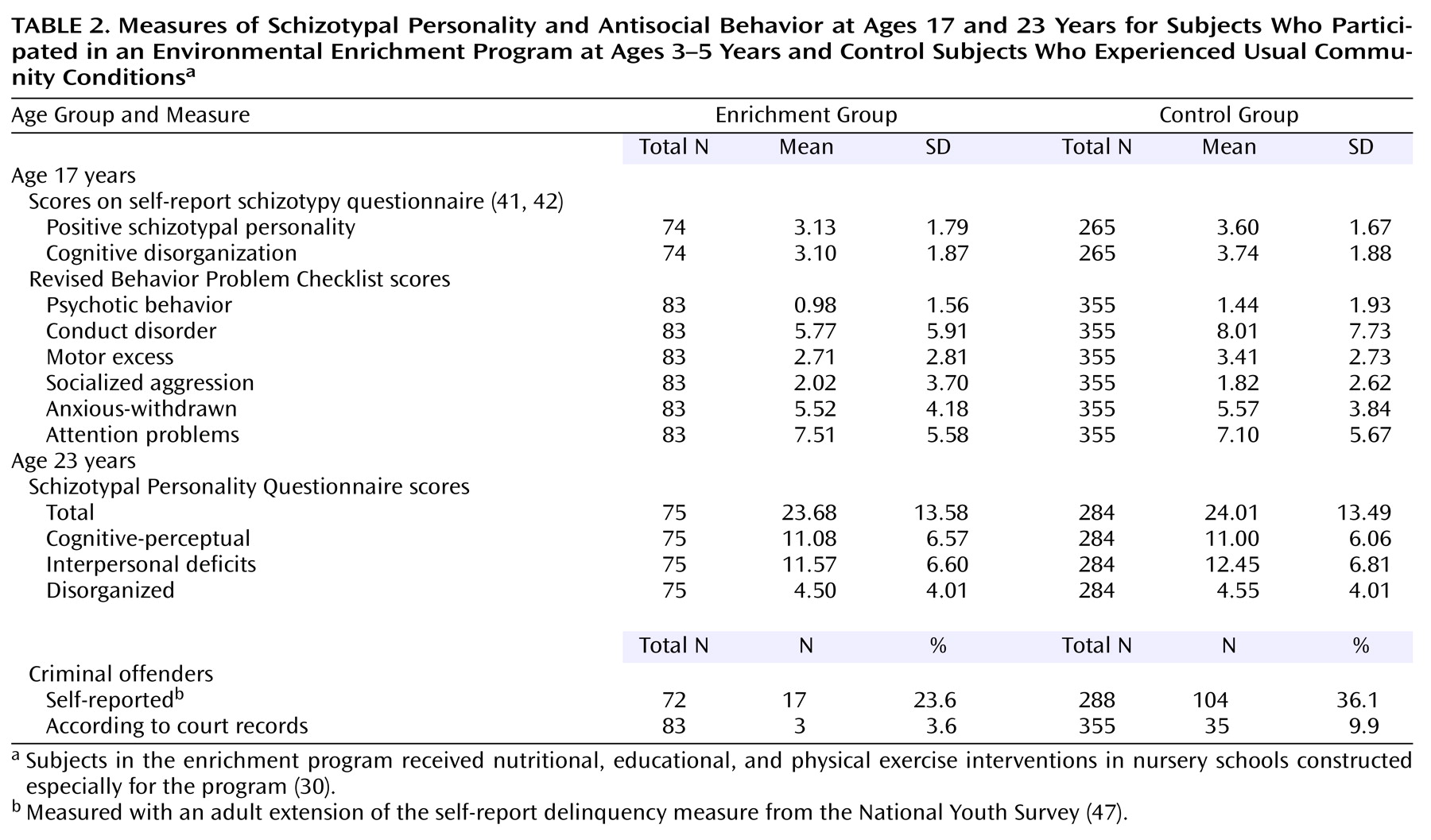

Discussion

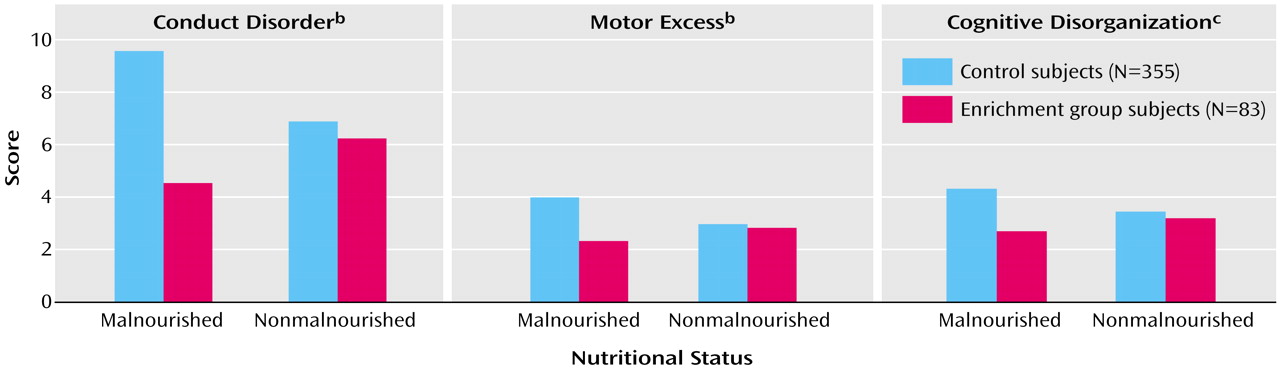

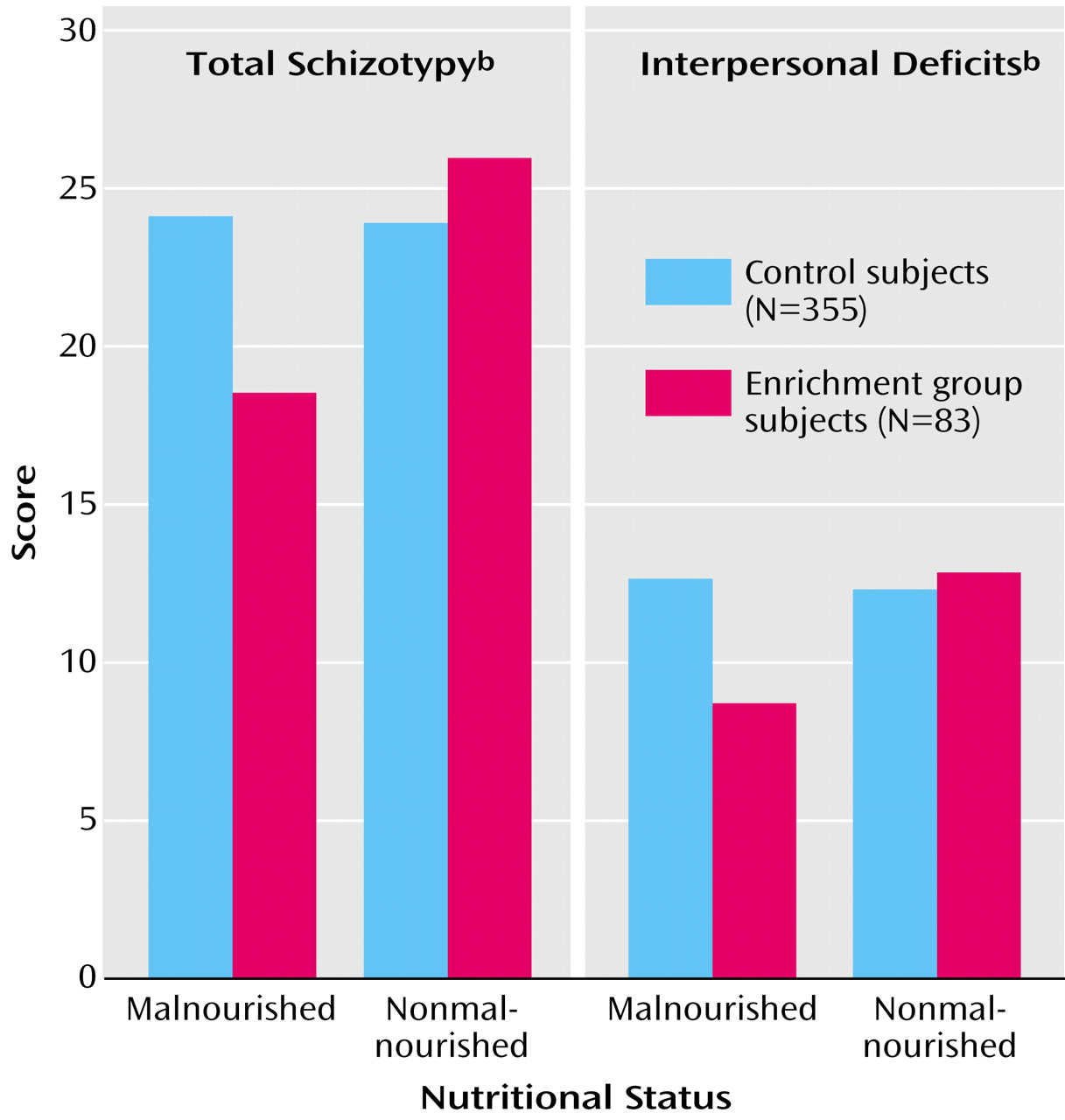

Nutritional, educational, and physical exercise enrichment at ages 3–5 years was associated with lower scores for schizotypal personality and antisocial behavior 14–20 years later, compared with usual community conditions. The beneficial effects associated with the intervention tended to be greater for children who were malnourished at age 3, particularly with respect to outcomes for schizotypal personality at ages 17 and 23 and conduct disorder at age 17. The fact that the prevention program was associated with effects for two different forms of psychopathology that were assessed by using two different types of outcome measures (self-report and objective measures) at two follow-up points extending over 20 years indicates the robustness of the effects. The results cannot be attributed to pre-enrichment group differences in temperament, cognitive ability, nutritional status, autonomic reactivity, or demographic variables. To our knowledge, this program constituted the first attempt at primary prevention of schizotypal personality. The findings are consistent with an increasing body of knowledge that implicates an enriched, stimulating environment in beneficial psychological and behavioral outcomes

(48–

50) and have potential implications for the prevention of crime and schizotypal personality, particularly in populations at risk for malnutrition.

One limitation of this study was the inability to determine which component(s) of the intervention (nutrition, exercise, or education) accounted for the later beneficial effects. Nevertheless, children who were malnourished at age 3 years were significantly more likely to benefit from the program at age 17 years and at age 23 years, compared with children who were not malnourished at age 3 years. Scores at age 17 years for subjects who were malnourished at age 3 years were 53.0% lower for conduct disorder, 41% lower for motor excess, 43.2% lower for psychotic behavior, and 32.4% lower for cognitive disorganization, compared with the scores at age 17 years for subjects who were not malnourished. Scores at age 23 years for subjects who were malnourished at age 3 years were 23.0% lower for total schizotypy and 31.6% lower for interpersonal deficits, compared with the scores at age 23 for subjects who were not malnourished at age 3 years. Nutritional deficits have been linked to both schizophrenia and schizoid personality disorder

(24,

25,

51) and also to antisocial behavior

(23). In particular, a recent double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial has shown the effectiveness of nutritional supplements in reducing antisocial and violent behavior in prisoners

(52). It is conceivable that aspects of the nutritional intervention such as fish supplementation could benefit brain function because omega-3 fatty acids have been reported by some to have beneficial effects on both schizophrenia

(53–

55) and externalizing behavior problems

(56–

59). In contrast to nutrition, psychophysiological status was not a significant moderator. Taken together with the findings of other successful early prevention programs that have manipulated nutrition

(28), the current findings suggest, but do not prove, that the nutrition component of the enrichment program may account for some of the benefits.

Alternative hypotheses must also be considered. For example, the prevention program included 2.5 hours each day devoted to physical exercise and outdoor play, and it is conceivable that exercise by itself could account for a significant proportion of the observed effects. Exercise in animals is known to increase mRNA in the hippocampus and to have other beneficial effects on brain structure and function

(60). Furthermore, the effect of environmental enrichment in producing neurogenesis in mice has been attributed to the sole effects of running, independent of other components of enrichment such as maze training

(13). As such, physical exercise could both benefit brain functioning and protect individuals from developing schizotypal personality and antisocial behavior, both of which have been linked to structural and functional brain deficits

(15–

18,

61). Another hypothesis that needs to be considered is that the increased social interaction with positive, educated preschool teachers in the experimental enrichment program may in part account for the beneficial effects of the prevention program. Alternatively, it may be unreasonable to focus on any single component of the intervention. Instead, the multimodal nature of the prevention program, which incorporated social and cognitive components along with nutrition and exercise components, may have facilitated interactions between these components that critically affected later development. Follow-up studies that both replicate the multimodal enrichment strategy as well as tease apart the individual components could usefully address this issue.

One prior study has shown that educational enrichment has long-term effects in reducing antisocial and criminal behavior

(28). Thus, it is possible that the educational component of the prevention program could have accounted for the long-term reduction in criminal offending. In the previous study, the participants in the educational enrichment program were children from poor homes, and it has been argued that enrichment may particularly benefit children affected by social adversity

(62). No support was found for this argument in the current study, as social adversity did not moderate the effects of the enrichment program. Instead, children affected specifically by malnutrition were more likely to benefit from the enrichment. Consequently, nutritional status in particular, rather than social adversity in general, may be a particular factor to consider in future prevention programs intended to address schizotypy and antisocial behavior.

The fact that the prevention program was associated with lower levels of schizotypal personality in late adolescence and in early adulthood in the malnourished group may help intervention efforts aimed at preventing or delaying the onset of schizophrenia

(2,

3). Schizotypal personality is a disorder that shares with schizophrenia a range of neurocognitive, neurophysiological, genetic, psychophysiological, and symptom characteristics

(21,

63) and has much in common with the prodromal, prepsychotic stage of schizophrenia. If features of schizotypal personality can be attenuated by early environmental enrichment, it is possible that the development of the prodromal features of schizophrenia may also be reduced, in turn delaying or preventing the onset of schizophrenia itself

(3,

64). The fact that one of the strongest effect sizes in this study was obtained for interpersonal deficits in the malnourished group at age 23 years (d=0.56) is of particular relevance, as these negative schizotypal traits feature strongly in the schizophrenia prodrome, as described in DSM-IV

(65,

66). Despite these findings, it must be reemphasized that this study showed only lower levels of schizotypal personality in a nonselected group, and it remains to be seen whether such prevention efforts can achieve results of clinical significance in relation to schizophrenia itself, as have been achieved with secondary prevention efforts

(65).

Although the prevention program was associated with a significantly lower conduct disorder score for subjects at age 17 (d=0.44), we caution that the effect size for subjects at age 23 years was smaller (d=0.26 for self-reported criminal offending; d=0.22 for criminal offending according to court records). In this study, the level of criminal offending at age 23 years according to self-reports was significantly lower in the enrichment group than in the control group (p<0.05). The level of criminal offending by age 23 years according to court records was 63.6% lower for the enrichment group than for the control group (which equals or exceeds effects found in short-term intervention studies

[67]), but the difference failed to reach statistical significance (p=0.07). On the other hand, base rates for criminal offending according to court records were lower than those for self-reported offending, and the possibility that floor effects precluded statistical significance must also be considered. A recent review of prevention programs for crime showed that even the very few model prevention programs that have shown success rarely if ever show effects beyond the teenage years

(67). The large majority of prevention programs do not start early in life, when the pathway to antisocial behavior is believed to begin

(68,

69). On the other hand, it may be questioned why any effect 20 years later was associated with a prevention program that lasted only 2 years early in life. Although stronger long-term effects may be expected of a longer environmental enrichment program, it has been found that early withdrawal from an environmental enrichment doubles the number of new hippocampal cells in mice, compared to more sustained enrichment

(70). Thus, some long-term beneficial effect of the 2-year enrichment is not inconceivable. Future studies may assess whether a booster enrichment session later in childhood leads to stronger effect sizes for criminal behavior in adulthood.

In conclusion, these initial findings suggest that early environmental enrichment is associated with lower levels of antisocial behavior and schizotypal personality in adulthood and that benefits are greatest for children with poor nutrition. We caution that findings from a country that was still developing when the prevention program was conducted cannot be directly extrapolated to more developed countries such as the United States. Nevertheless, the findings may be particularly relevant to poor rural areas of the United States, such as the Mississippi delta region, and also to U.S. inner cites, where rates of both malnutrition and behavioral problems in children are relatively high

(71,

72).