Age at onset for any illness may be a marker of etiologic and genetic heterogeneity. For this reason, the study of age at onset has been useful in evaluating phenotypes of a disorder to assist in diagnosis, in determining the etiology or prognosis of the disorder, and possibly in preventing and treating the disorder.

We used this data set to examine the following questions about age at onset of the first episode of bipolar illness:

Results

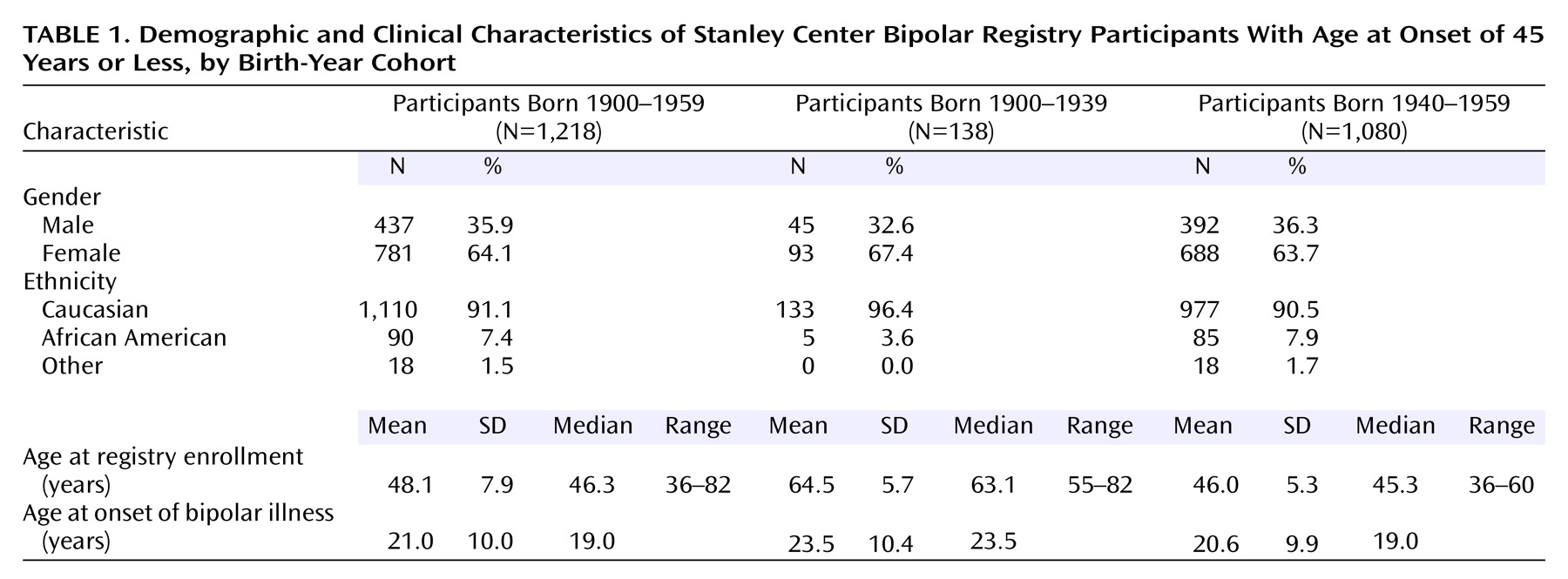

Demographic characteristics and age at onset of the first illness episode for the two birth-year cohorts are presented in

Table 1.

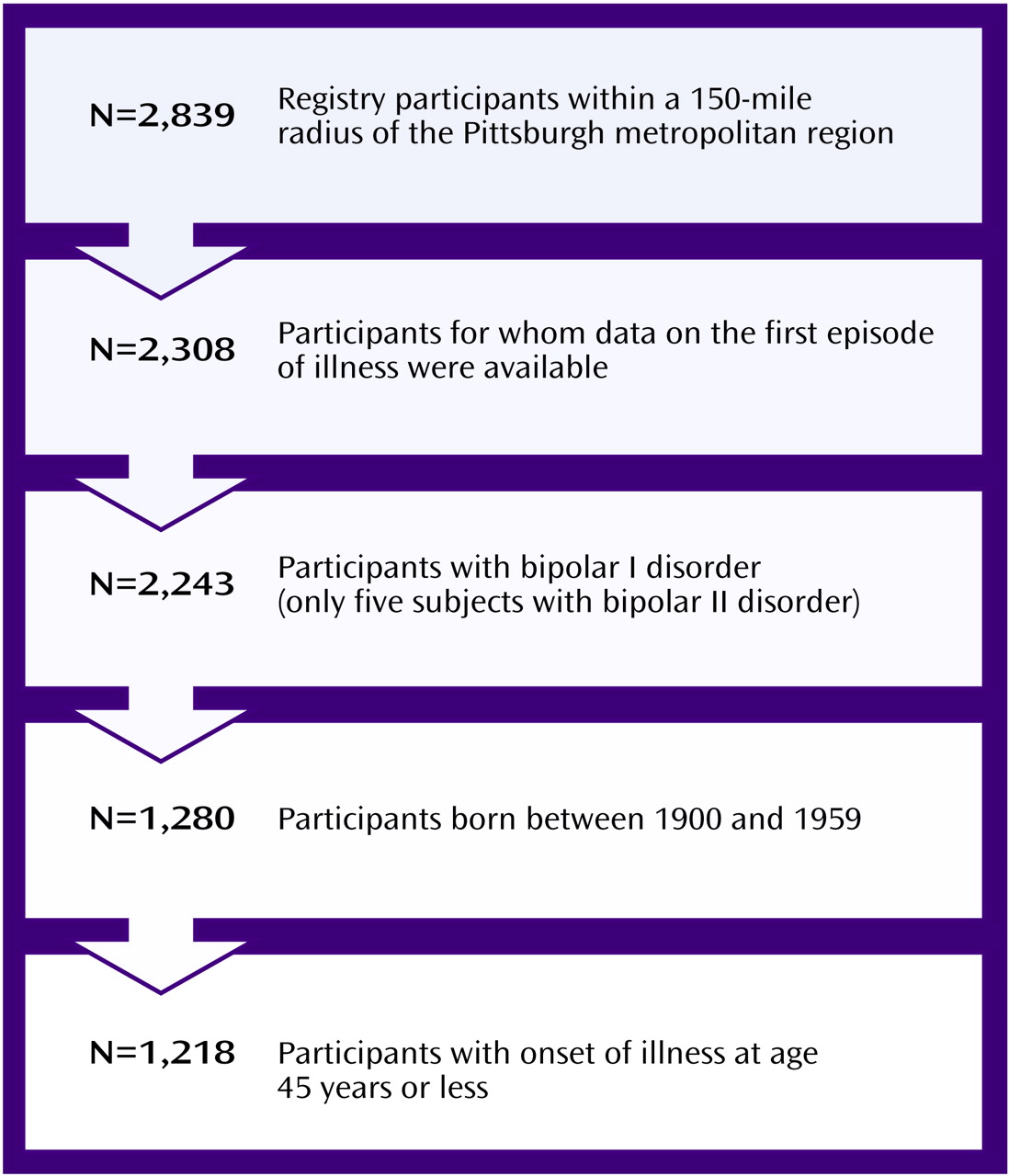

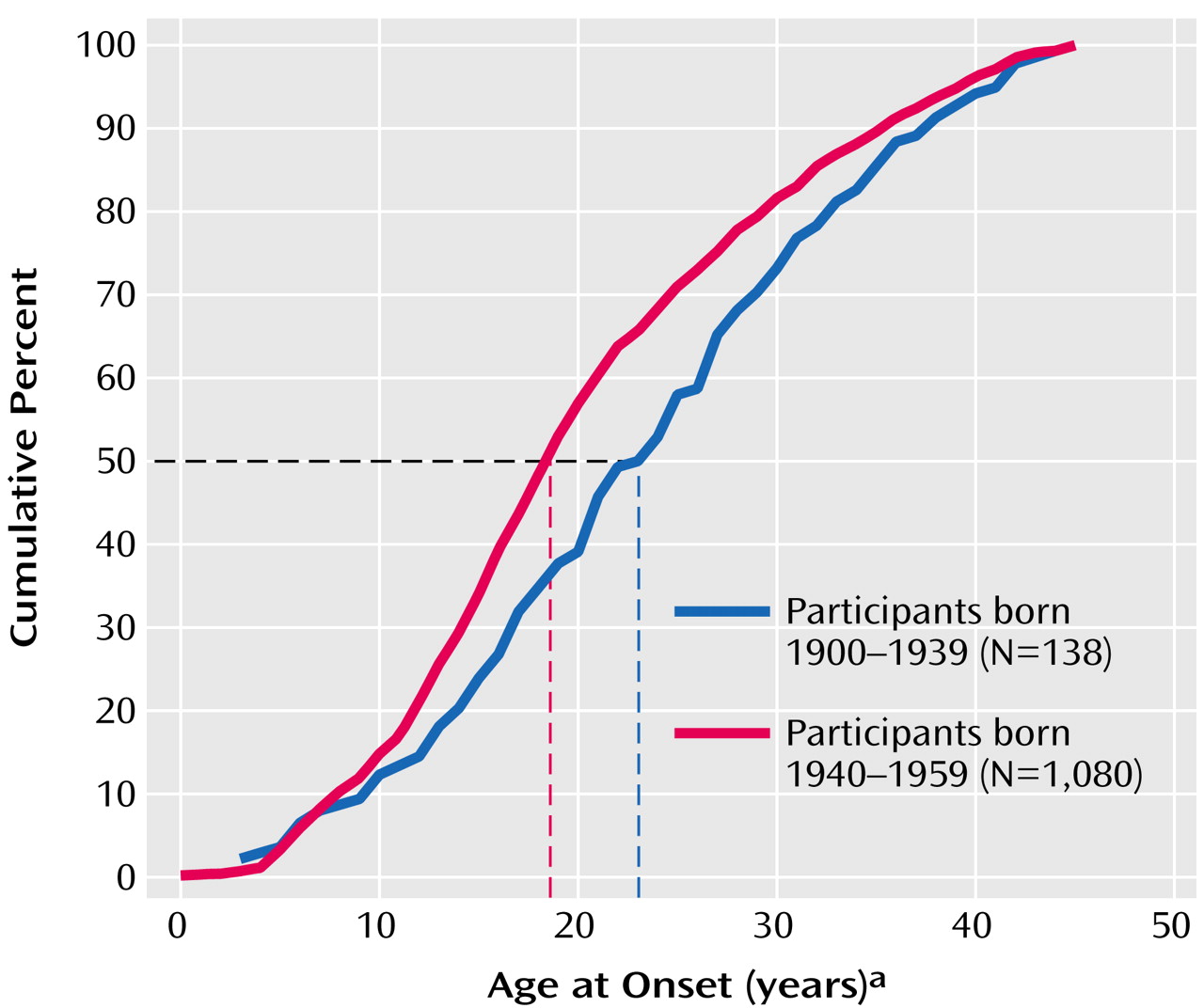

Data regarding the age at onset are presented as cumulative percentages in the two birth-year cohorts in

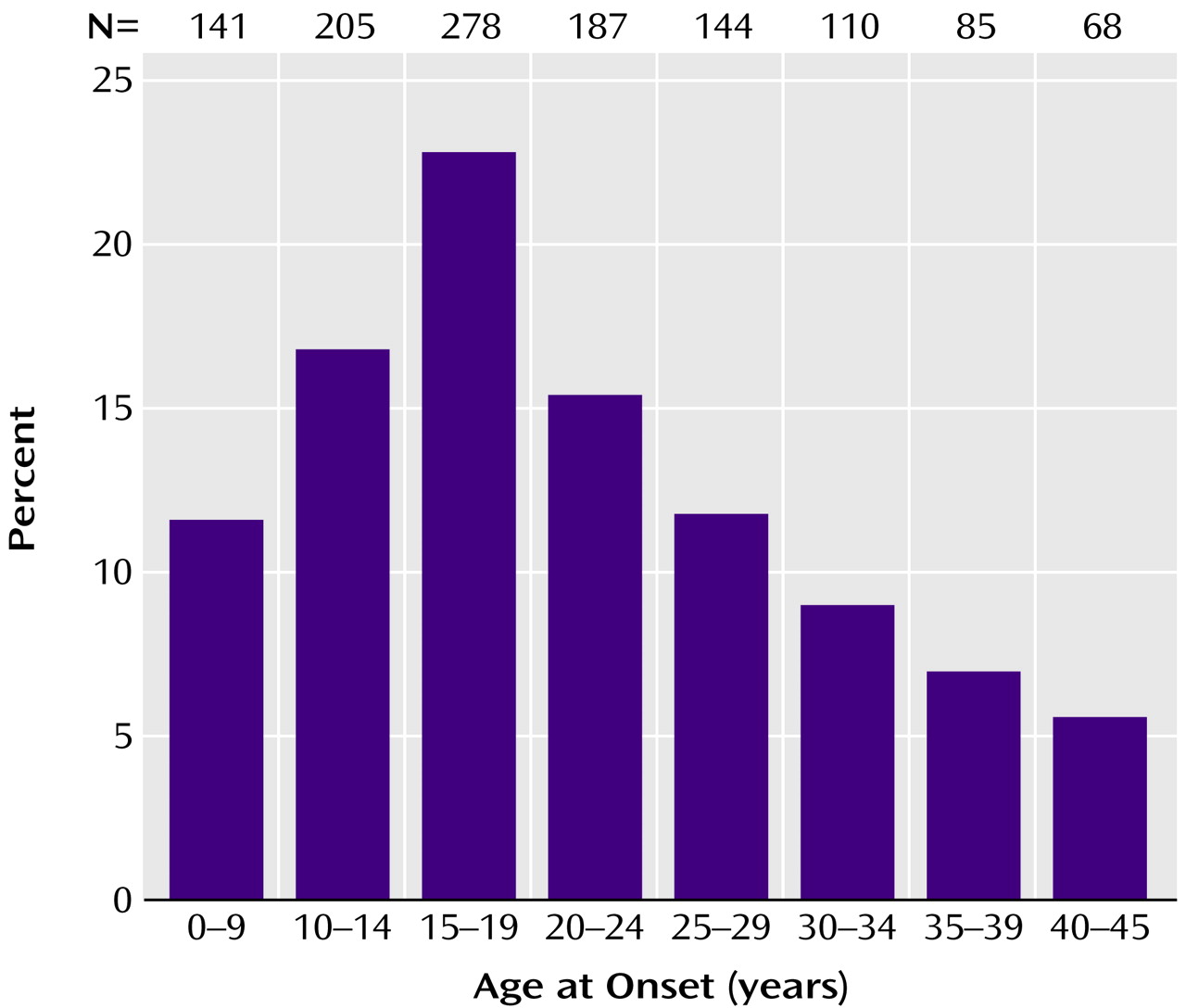

Figure 2 and as frequency histograms for different age intervals in the entire sample in

Figure 3 and in the two birth-year cohorts in

Figure 4. The percentages of subjects in each cohort presenting with major depression, mania, or a mixed state at onset of illness are presented in

Figure 5. As there were only five subjects of African American descent in the cohort born from 1900 through 1939, racial differences between the two cohorts for age at onset could not be reliably estimated.

Based on visual inspection of the distribution of the age-at-onset plots, it was determined that the data for age at onset were not normally distributed. Therefore, these data were subjected to square-root transformation before further analyses. As

Table 1 shows, there was nearly a 3-year earlier mean age at onset of the first episode of bipolar illness in the 1940–1959 birth cohort, compared with the 1900–1939 cohort (t=2.97, df=1,216, p<0.004). The median age at onset of the first episode differed in the two birth-year cohorts by 4.5 years (

Figure 2). The age at onset was correlated with the birth year in the entire cohort (r=0.16, N=1,218, p<0.0001). When this correlation was reviewed for the 1900–1939 birth cohort, it was not statistically significant (r=0.03, N=138, p=0.75), whereas there was a small but statistically significant correlation in the 1940–1959 cohort (r=0.08, N=1,080, p<0.009).

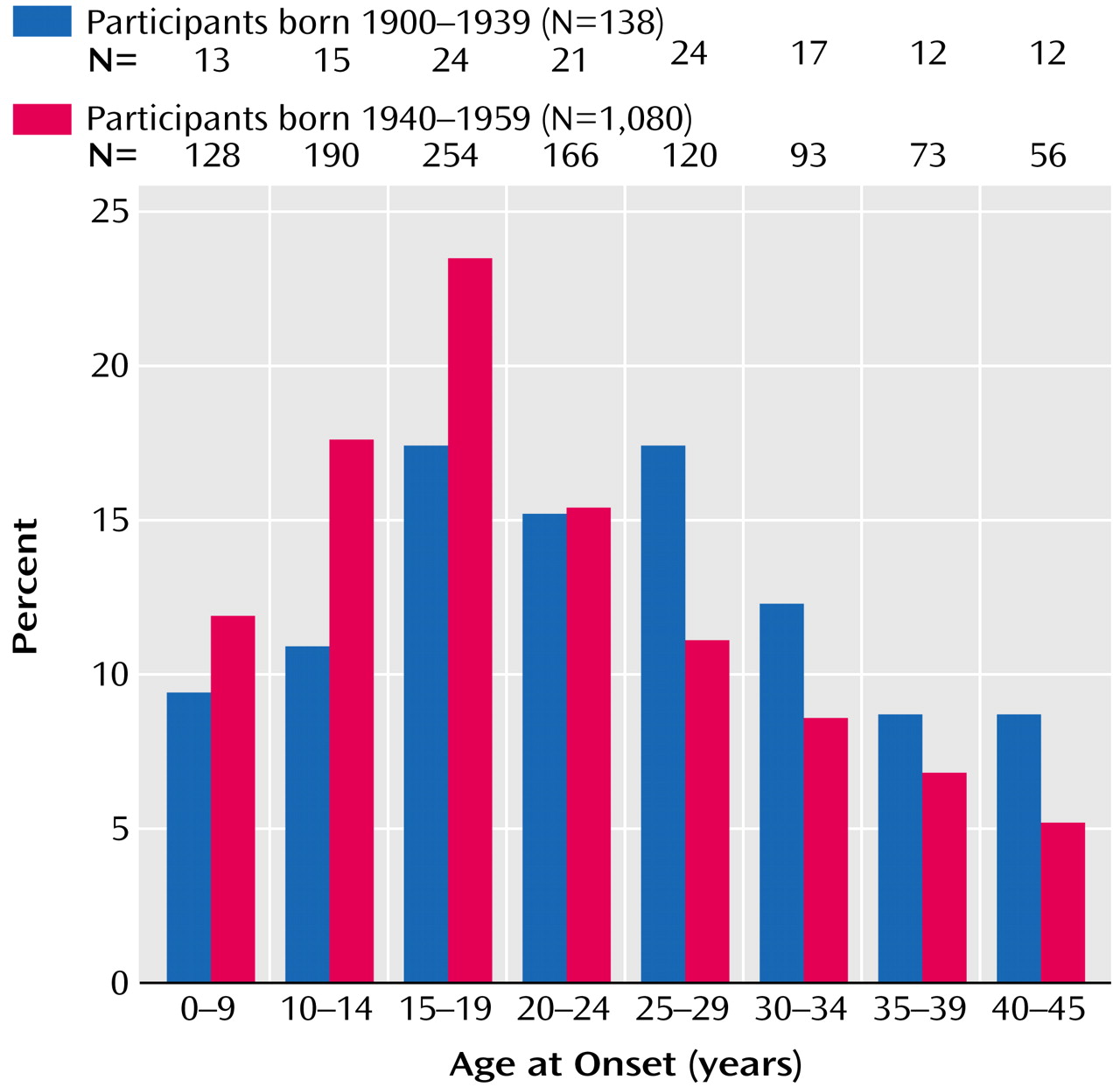

In the entire sample, more than 75% of the subjects had their first episode by age 29 years, with a peak between 15 to 19 years (

Figure 3). The 1940–1959 cohort had a greater proportion of subjects (53%) with onset of the first episode before age 19 years (

Figure 4), compared with the 1900–1939 cohort (37%) (χ

2=11.44, df=1, p<0.001).

There was no statistically significant difference in the mean age at first episode between men and women in the entire sample (men: mean=21.5 years, SD=10.1; women: mean=20.6 years, SD=9.9) (t=1.55, df=1,216, p=0.12) and in each birth-year cohort.

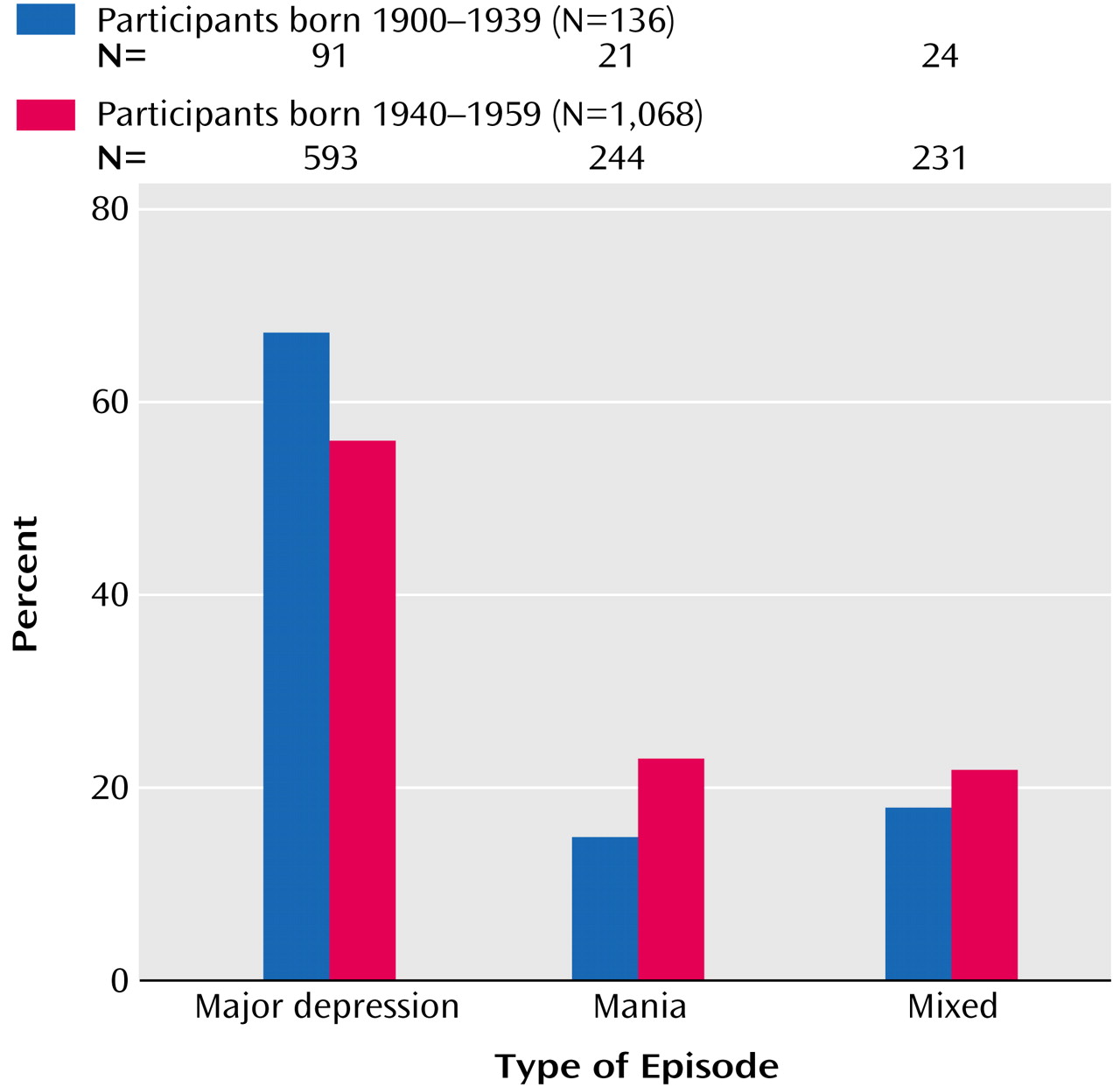

The two cohorts were significantly different in the proportion of subjects who reported that their first episode was major depression, mania, and a mixed state (

Figure 5). In the 1900–1939 cohort, the first episode was a depressive episode for 91 subjects (67%), a manic episode for 21 subjects (15%), and mixed for 24 subjects (18%), compared with 593 subjects (55%), 244 subjects (23%), and 231 subjects (22%), respectively, in the 1940–1959 cohort (χ

2=6.66, df=2, p=0.04).

In the entire sample, the proportions of men and women presenting with a first episode of major depression, mania, or a mixed state were significantly different. Among women, the first episode was major depression for 457 subjects (59%), mania for 147 subjects (19%), and mixed for 168 subjects (22%), compared with 227 subjects (53%), 118 subjects (27%), and 87 subjects (25%), respectively, among men (χ2=11.12, df=2, p<0.0004).

Gender differences in the type of episode at onset were not evident in the 1900–1939 cohort. Among women, 65 subjects (71%) reported a first depressive episode, 13 subjects (14%) reported a manic episode, and 14 subjects (15%) reported a mixed episode, compared to 26 men (59%), eight men (18%), and 10 men (23%), respectively (χ2=1.86, df=2, p=0.39). In contrast, in the 1940–1959 cohort, 392 women (58%) reported major depression as the first episode, 134 women (20%) reported mania, and 154 women (22%) reported a mixed episode, whereas 201 men (52%) reported major depression, 110 men (28%) reported mania, and 77 men (20%) reported a mixed state (χ2=10.5, df=2, p<0.006).

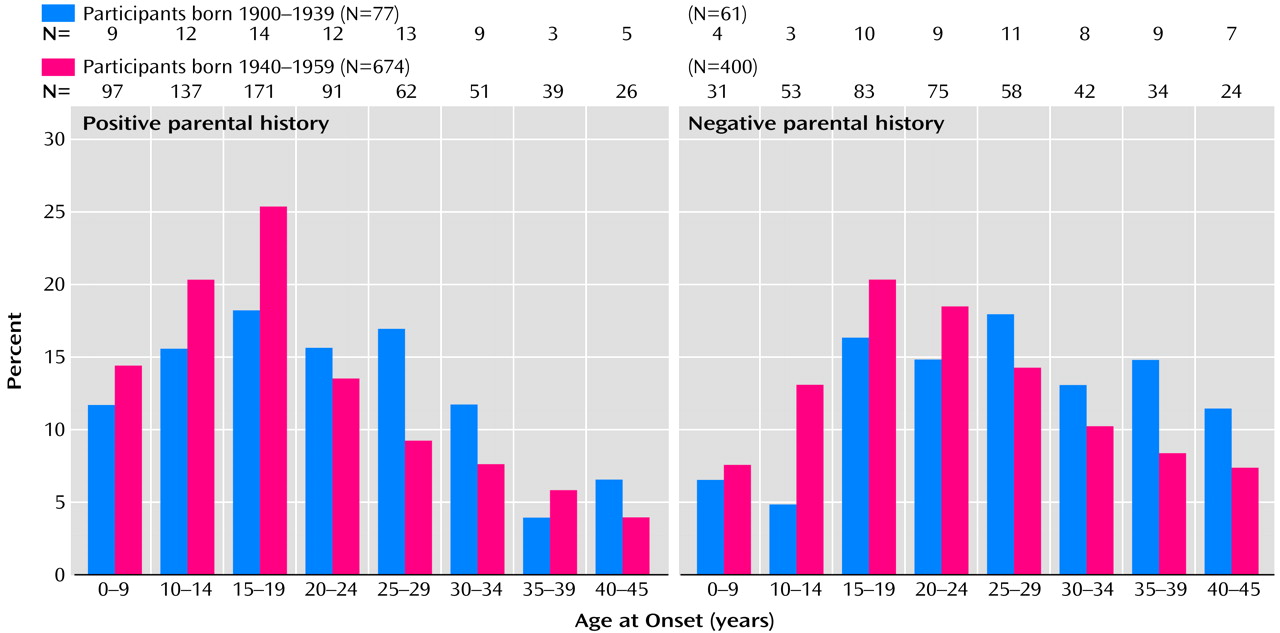

Within each birth-year cohort, subjects who reported that either parent had a diagnosis of major depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia had an earlier age at onset of the first episode than subjects without such a parental history (

Figure 6). In the entire sample, the age at first episode for the 751 subjects with a parental psychiatric history was earlier (mean=19.4 years, SD=9.7, median=18.0 years) than that for the 467 subjects without such a parental history (mean=23.4 years, SD=10.0, median=22.0 years) (t=6.93, df=1,216, p<0.0001). In the 1900–1939 cohort, the mean age at illness onset among subjects with a parental psychiatric history was 21.3 years (SD=10.0), compared with 26.3 years (SD=10.2) for those without a parental psychiatric history (t=2.80, df=136, p<0.006). In the 1940–1959 cohort, the mean age at illness onset for subjects with a parental psychiatric history was 19.2 years (SD=9.6), compared with 23.0 years (SD=9.9) for those without such a history (t=6.23, df=1,078, p<0.0001).

To answer the question of whether age at onset has become even earlier (14 years of age or less, i.e., prepubertal onset) in recent years, comparisons were made not only between the two birth-year cohorts described earlier but with a separate cohort born during the years 1960–1969 (N=570). The proportions of subjects in the three birth-year cohorts who had their first illness episode at age 14 years or earlier were significantly different. In the 1900–1939 cohort, 28 subjects (15.6%) had their first episode by age 14 years, compared with 318 subjects (28.9%) in the 1940–1959 cohort and 196 subjects (36.7%) in the 1960–1969 cohort (χ2=30.29, df=2, p<0.0001). The odds ratio for onset of disorder by age 14 was 2.19 (95% confidence interval [CI]=1.43–3.35) for the 1940–1959 cohort and 3.12 (95% CI=2.02–4.84) for the 1960–1969 cohort, compared with the 1900–1939 cohort.

To evaluate faulty recall of the age at onset of the first illness episode, the calculated age at onset (by using the actual date of birth and the reported age at onset, requested halfway through the interview) was a mean of 6.0 months (SD=5.6) later than it should have been given the reported date of birth in the 1900–1939 cohort. In the 1940–1959 cohort, the age at onset was reported to be a mean of 3.0 months (SD=2.1) earlier than it should have been. Both of these differences were well within a 1-year time frame. Furthermore, the self-reported age at onset of the first episode (mean=22.4 years, SD=9.9) closely matched the age-at-onset data derived from the SCID (mean=22.5 years, SD=8.3). The minor difference was not statistically significant, and the correlation between the two assessments for the subset of subjects in both the registry and the SCID database was high and statistically significant (r=0.81, N=65, p<0.0001).

Discussion

Operational definitions of age at onset for psychiatric illnesses have varied from the first onset of symptoms to the first onset of a full episode of illness with functional impairment that may or may not have required treatment, including psychiatric hospitalization. Each of these definitions is clinically relevant and represents important landmarks in the course of the illness, but, nonetheless, discrepancies in the specifications of the definition of age at onset may easily shift the reported time for onset of illness from several months to nearly 10 years

(16). The present data reflect the first full episode of bipolar illness.

Limitations of this report include the voluntary and retrospective nature of the bipolar disorder case registry, compared with a prospective epidemiological registry. However, the subjects’ ability to accurately self-identify their illness

(14) and to give details about the first episode of their illness

(13) and the limitation of recall bias to a range of a few months suggest that while these data may not be ideal, they still provide a reasonable estimate of age at onset of the first episode of bipolar illness.

What factors may account for these results? One important consideration is diagnosis. Has the diagnosis of bipolar illness become so much broader in recent times that the subjects with an earlier onset of illness would not have been classified as having bipolar disorder in the past? This explanation is possible, but it is not likely to fully account for the current findings. Such an explanation would be more likely if a significant proportion of the subjects’ diagnoses were bipolar spectrum disorders. However, this data set, as with many others used in assessment of age at onset, concentrated on bipolar I disorder. Nonetheless, it is pertinent that the earlier birth-year cohort may have been less likely to receive a bipolar disorder diagnosis in childhood or early adolescence, and this possibility constitutes a limitation of this study.

Many studies of age at onset are based on retrospective recall by subjects. Faulty recall may lead to either underreporting or inaccurate reporting of age at onset. Is it possible that faulty recall by both birth-year cohorts led to disparate reporting of age at onset of bipolar illness in this study? A systematic reporting of later age at onset by the earlier birth-year cohort (a phenomenon sometimes referred to as the “Little Bo-Peep” effect) could in fact be responsible for this reported difference. However, other authors who have evaluated age at onset using different methods have also noted an earlier age at onset in subjects born after 1940

(2,

4). Furthermore, although there were minor differences between the two cohorts in accuracy of recall of age at onset, these differences were well within the time frame of a few months. However, this faulty recall was evaluated within a single interview, which does not preclude the possibility of a systematic misreporting of age at onset that may have influenced the results presented in this paper. It is interesting to note that self-reported age at onset of the first episode in this report was close to that recorded in the subgroup of subjects interviewed with the SCID

(14).

Another possibility is that assortative mating may be involved in earlier age at onset of bipolar illness. For instance, because of illness-associated factors, subjects with bipolar affective disorders may marry or cohabit, giving rise to the possibility that their offspring may express the illness sooner. The present data suggest that subjects in both cohorts were more likely to have a nearly 4–5-year earlier age at onset if either parent had major depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia. However, in the absence of systematic data on genetic history, the present study cannot answer this question definitively. Similarly, these data cannot be used to examine the phenomenon of “anticipation” of illness in the offspring of parents with bipolar illness

(17).

Is it possible that the earlier and more extensive use of antidepressants or stimulants in younger populations led to an earlier expression of bipolar illness? The present data cannot be used to examine this issue conclusively, although some reports in the literature have appeared to support this contention

(9–

11). In adults with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, the use of imipramine as monotherapy in maintenance treatment was associated with a 53% rate of mania, compared to a 28% rate for those receiving the combination of lithium and imipramine

(18). Findings from such data sets led to the clinical practice of combining a mood-stabilizing agent such as lithium with an antidepressant, if one were needed in the treatment of depression in bipolar disorder. Nonetheless, the issue of antidepressant- or stimulant-associated hypomania/mania or cycle acceleration remains controversial. The data for children and adolescents in this regard are even less clear.

What then are the implications of these data? First, prospective epidemiological studies of childhood and adolescent populations are needed to accurately estimate the prevalence and incidence of bipolar illness and either affirm or refute the clinical experience suggesting that this condition is not uncommon in childhood and adolescence. Also, it will be important to determine if rates of prepubertal mania differ significantly between the United States and other countries, as suggested by one report

(9). Second, these data may have implications for treatment. For instance, the use of stimulant or antidepressant medications in children may need to be considered carefully, especially in those with an initial diagnosis of ADHD, depressive disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder who may eventually turn out to have bipolar illness. Careful delineation of family history for evidence of affective disorder or psychoses, symptoms of bipolar disorder, and psychotic depression may be clinically relevant for an accurate diagnosis for these young people. Third, recent survey data from the U.S. National Depressive and Manic Depressive Association have suggested a long delay before adults with bipolar illness receive a correct diagnosis

(12), and the situation could possibly be worse for children and adolescents with this disorder

(11). Fourth, the abuse of stimulant street drugs such as cocaine by adolescents could mask the onset of mania and further delay an accurate diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Further, as women (and men) are more likely to present with major depression as the first episode of bipolar disorder, it is both possible and likely that they may receive unimodal antidepressant trials initially and that this encounter could occur in a primary care setting. Therefore, it may be helpful for psychiatrists to educate and assist primary care physicians in screening for bipolar illness.

Finally, the data derived from the bipolar disorder registry

(13) used in this study and from other studies

(19,

20) suggest that an earlier onset of the first episode of bipolar illness is often associated with chronicity as well as serious functional impairment. A natural extension of this issue is whether delayed diagnosis (implying either the lack of treatment or inappropriate treatment) contributes to this functional impairment. For decades, it has been argued in medicine that rapid recognition and treatment of many illnesses result in better functional outcomes for patients. These data on age at onset of bipolar illness support a similar approach to recognition and treatment of these disorders.