Neuropsychological Variables

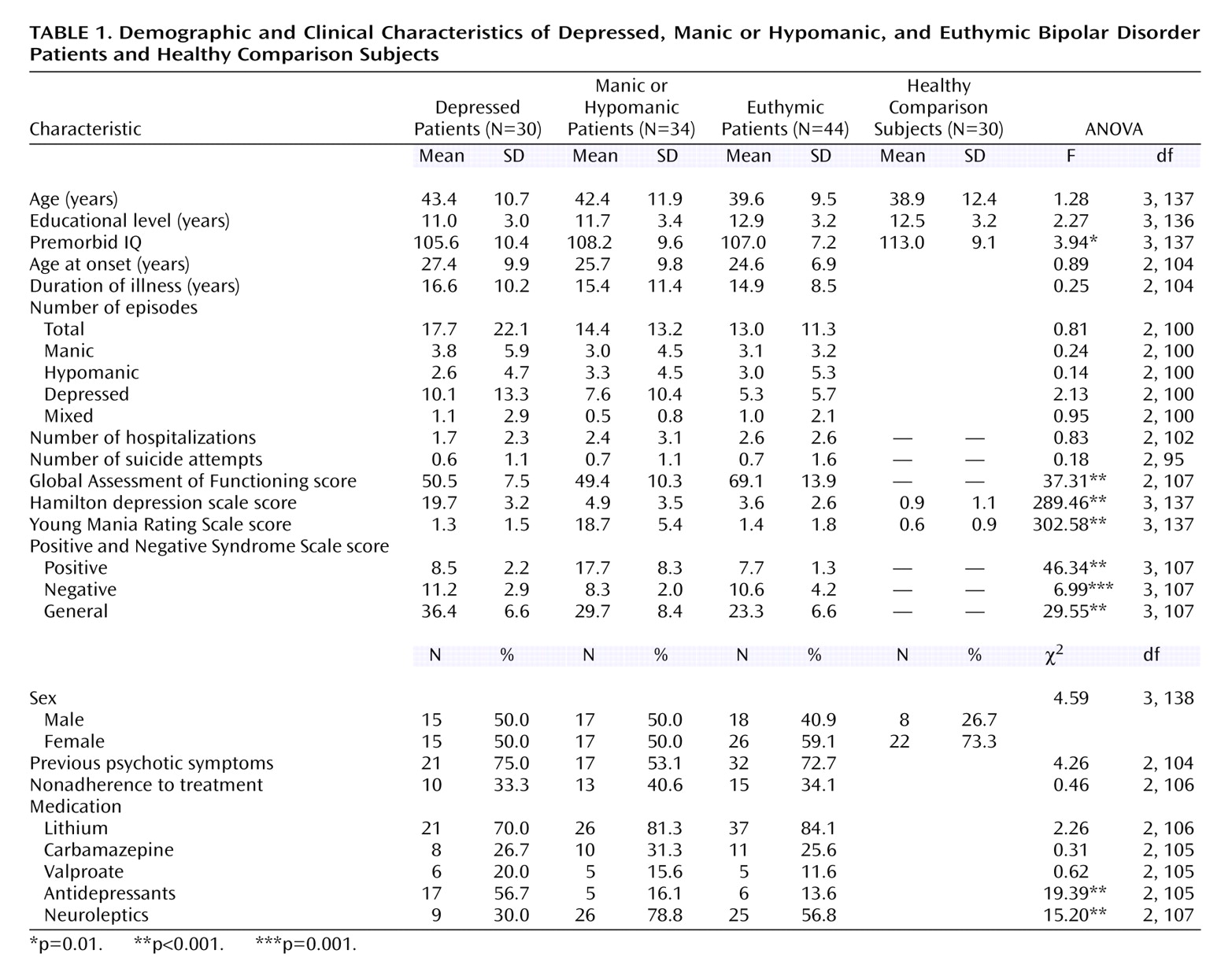

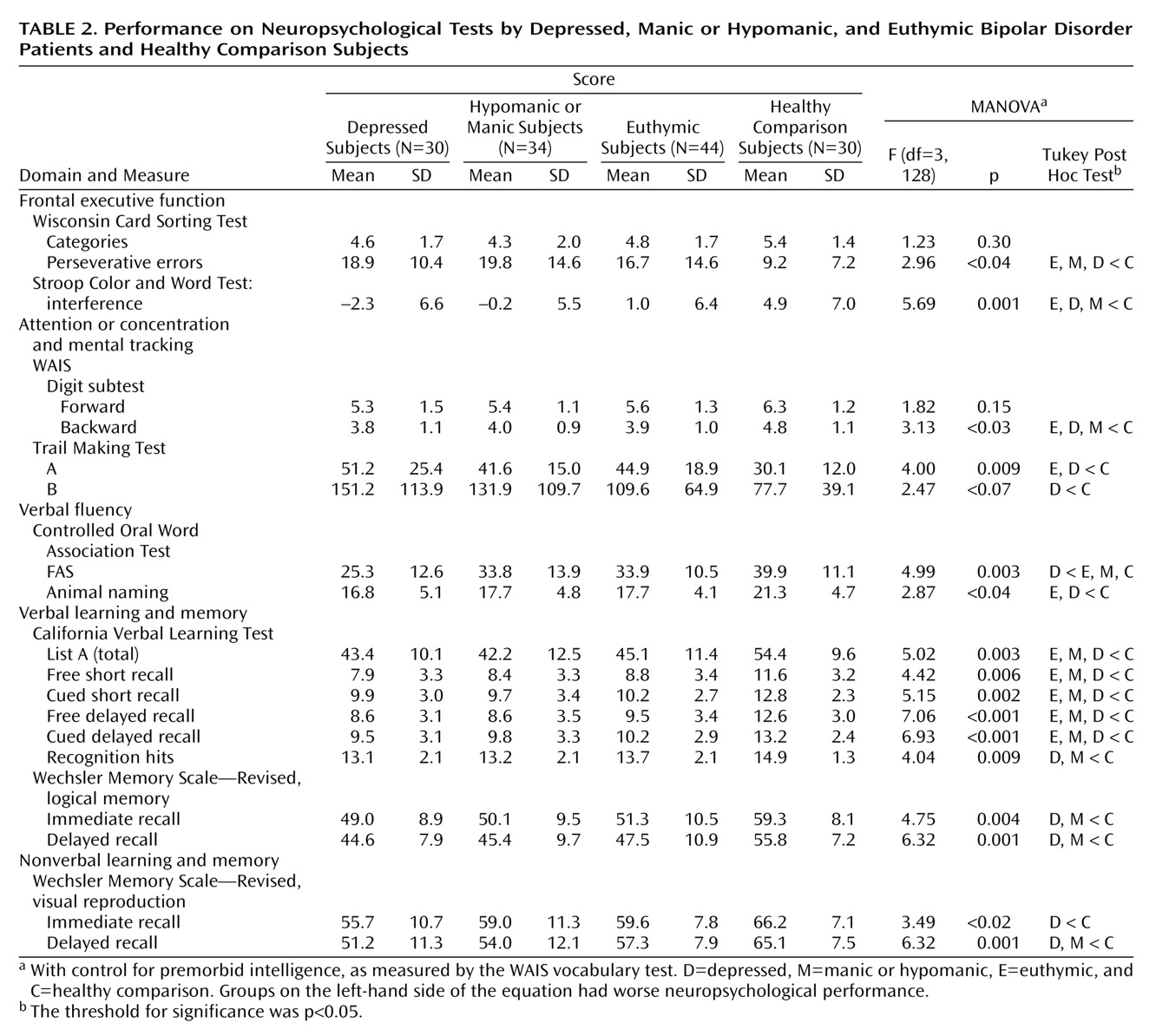

Neuropsychological performance across manic or hypomanic, depressive, and euthymic bipolar patients and their relation to the healthy comparison subjects is presented in the

Table 2. MANOVA yielded Pillai’s F=1.66, df=45, 321, p=0.007 for the main effect, indicating that there were overall differences in neuropsychological performance between the groups. The results revealed the presence of specific cognitive dysfunctions among bipolar patients, regardless of clinical state, after control for estimated premorbid IQ. These results did not substantially change after the introduction of other possible confounding variables, such as age and years of education, so we only introduced as a covariate the estimated premorbid IQ.

For 16 of 19 comparisons, the differences reached statistical significance (p<0.05). Acute and remitted bipolar patients displayed poor performance in the verbal memory domain. All patient groups scored lower than the comparison subjects on the California Verbal Learning Test learning task. Short and long delay recall, in both free and cued forms, were significantly poorer in all bipolar groups than in the comparison subjects. The comparison subjects recalled significantly more words than did the patients, regardless of their clinical state. Only the acutely ill patients had significantly poorer performance on the California Verbal Learning Test recognition task in verbal immediate and delayed recall (WMS-R logical memory subtest) and in visual delayed recall (WMS-R visual reproduction subtest) than the comparison subjects. The depressed patients were also impaired in visual immediate recall in relation to the comparison subjects.

All patient groups showed neuropsychological impairment on the Stroop Color and Word Test interference score, as well as in other frontal executive tasks, such as the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test perseverative errors and digit subtest backward subtests, in relation to the healthy comparison subjects. Furthermore, regarding verbal fluency, also related to frontal executive function, the depressed patients had lower scores for phonemic fluency (the FAS subtest) than the other three groups. Moreover, the euthymic and depressed patients scored lower on category fluency (the animal-naming subtest). Finally, the depressed and euthymic bipolar patients scored lower on some attentional tasks (Trail Making Test A) than the comparison subjects.

Correlations Between Variables

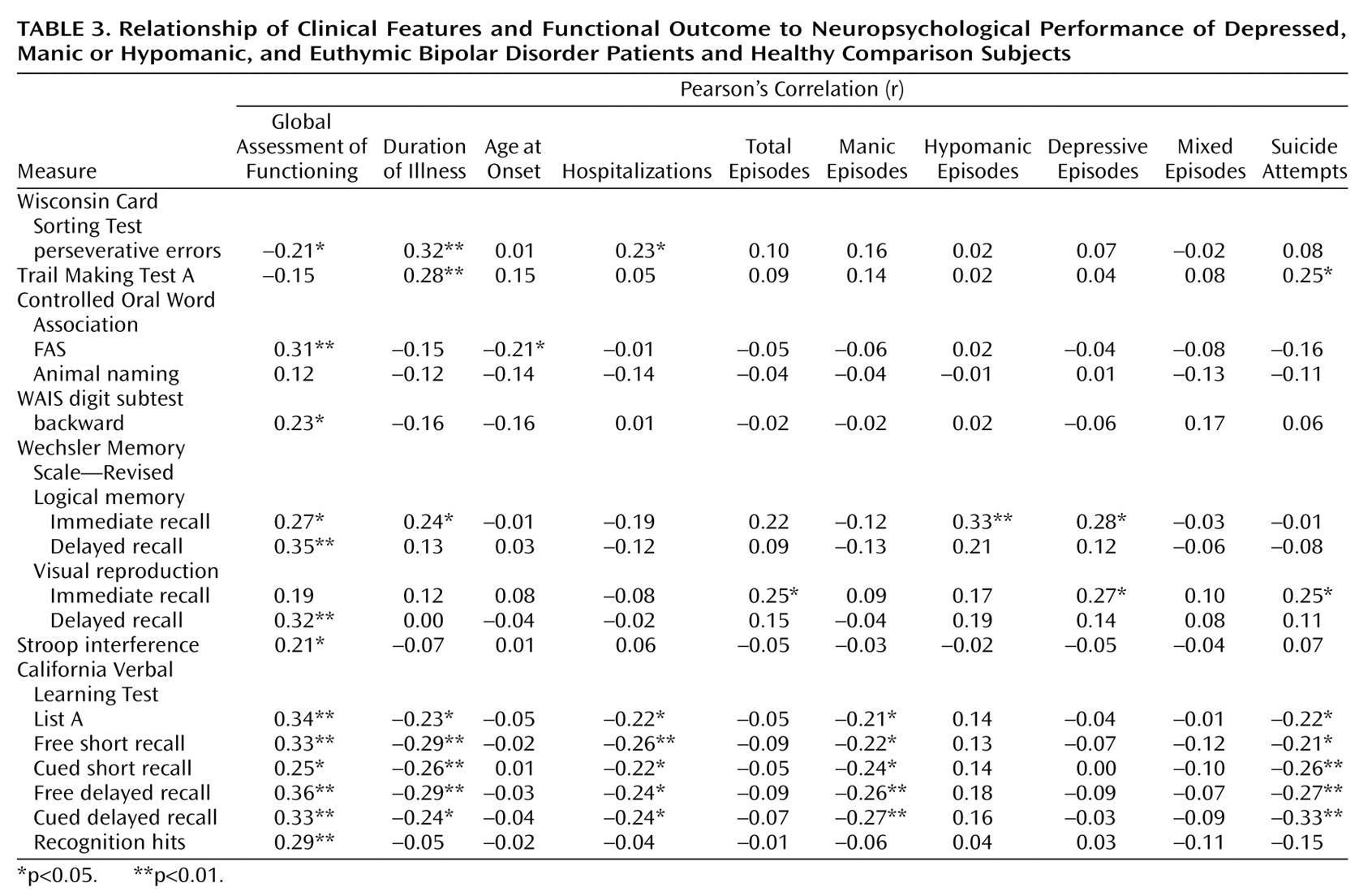

Pearson correlations (

Table 3) indicated that psychosocial functioning in bipolar patients was associated with neuropsychological measures rather than with clinical variables. No relationship was found between psychosocial functioning and chronicity (duration of illness), total episodes, types of episodes, or numbers of hospitalizations or suicide attempts, whereas social and occupational functioning was related to some measures of frontal executive function (the Stroop Color and Word Test, the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, the FAS subtest, and the digit subtest backward) as well as to learning and memory tasks (WMS-R subtests and the California Verbal Learning Test). Clinical variables were also associated with neuropsychological measures. Therefore, the patients with a longer duration of illness showed more memory dysfunctions, more slowness or diminished attention (the Trail Making Test A), and committed more perseverative errors (the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test). The numbers of hospitalizations and suicide attempts also were related to memory measures. When we separated different types of episodes, we observed that patients who had suffered more manic episodes showed more cognitive dysfunction in verbal learning and memory.

ANOVAs showed that bipolar patients with previous psychotic symptoms scored lower on the performance of verbal memory measures: logical memory subtest immediate recall (F=6.97, df=1, 97, p=0.01) and delayed recall (F=8.82, df=1, 97, p=0.004), California Verbal Learning Test learning task (F=15.01, df=1, 102, p<0.001), free short recall (F=22.15, df=1, 102, p<0.001), cued short recall (F=17.87, df=1, 102, p<0.001), free delayed recall (F=15.05, df=1, 102, p<0.001), and cued delayed recall (F=17.37, df=1, 102, p<0.001). The results did not differ when we included only the euthymic patients. The bipolar I patients scored lower than the bipolar II patients in the verbal memory domain, significantly so on the California Verbal Learning Test learning task (F=4.09, df=1, 103, p<0.05) and in free (F=5.02, df=1, 103, p<0.03) and cued (F=5.28, df=1, 103, p<0.03) short recall. No differences regarding neuropsychological measures were found between groups regarding lithium treatment, which was the most used mood stabilizer among the patients.

Occupational functioning was analyzed among the patient groups, and no significant differences were found (χ2=2.51, df=2, p=0.29). Hence, neuropsychological performance between patients showing “good” and “poor” occupational functioning was analyzed by using ANOVA. Significant differences were found between groups, so the patients with better occupational functioning performed better on the FAS (F=5.93, df=1, 102, p<0.02) and on all measures of verbal memory (California Verbal Learning Test): list A (F=13.73, df=1, 105, p<0.001), free short recall (F=12.99, df=1, 105, p<0.001), cued short recall (F=10.95, df=1, 105, p=0.001), free delayed recall (F=14.84, df=1, 105, p<0.001), cued delayed recall (F=13.49, df=1, 105, p<0.001), and recognition hits (F=8.36, df=1, 105, p=0.005).

Linear regression analysis with hierarchical methods showed that psychosocial functioning was associated with affective symptoms (the Hamilton depression scale and the Young Mania Rating Scale) (t=–5.63, df=95, p<0.001). In the subsequent block, neuropsychological variables were introduced stepwise. Only the California Verbal Learning Test learning task appeared in the equation (t=2.95, df=95, p=0.004); overall, the model reached significance (F=20.58, df=3, 95, p<0.001).