Major depressive disorder and related mood disorders are important diagnoses, in terms of both their high prevalence and high cost. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

(1) estimates the lifetime prevalence of major depression in the United States at 7.0% and the current prevalence at 4.1%. The direct and indirect costs of major depression in the United States are estimated at between $26 and $43.7 billion per year

(2), and major depression alone accounts for 11% of all years lived with disability worldwide

(3). Groups in the United States with a high prevalence of depression include the chronically medically ill

(4,

5), immigrants

(6), and women, young adults, and people with less than a college education

(7).

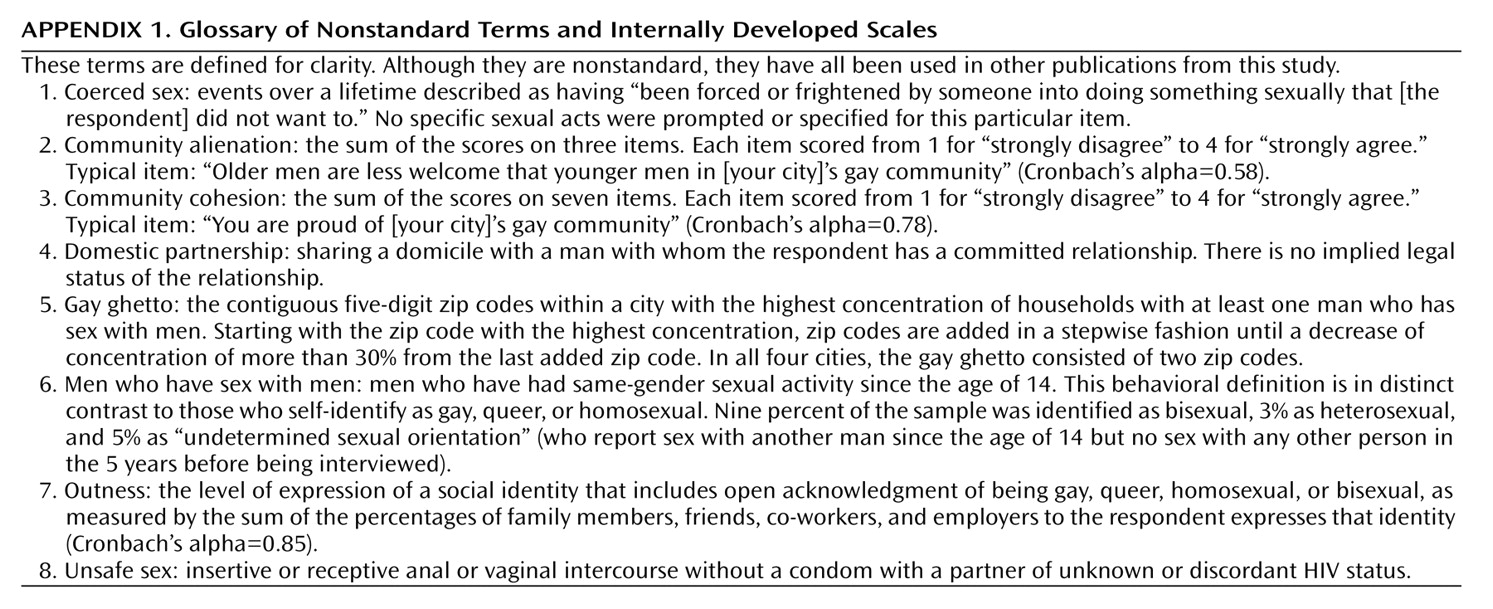

Accurate prevalence estimates require probability samples, a rarity in clinical research. Clinical research groups are usually convenience groups: people in treatment, either from a particular center or for a particular condition. Convenience groups are subject to selection bias, raising the question of whether similar people not in treatment, or in treatment elsewhere, would have similar characteristics. This is particularly problematic in trying to study a population defined by a nonclinical characteristic, such as men who have sex with men (

Appendix 1). Hooker

(8) showed that inferences based on psychoanalytic theory, derived from the treatment of men who have sex with men seeking to change their sexual behavior, were flawed by this bias; a convenience group of men who have sex with men not seeking treatment was no different from men in general. Similarly, men who have sex with men who were selected in gay bars have been shown to have a high rate of alcoholism compared to the general population

(9). It is not surprising that examination of non-bar-based convenience groups of men who have sex with men eliminated this difference

(10,

11).

While probability sampling eliminates many biases, probability samples of the general population in the United States have yielded small samples of men who have sex with men

(12–

14). These subsamples have been too small to power statistical analysis beyond prevalence estimates. The NEMESIS study

(15), with 82 men who have sex with men within a total sample of 2,878 adult men, showed that Dutch men who have sex with men were nearly three times as likely to have a DSM-III-R-defined mood disorder than heterosexual men. Generating probability samples of men who have sex with men requires extensive (and expensive) screening, so earlier probability samples have been limited to “gay ghettos”

(16) in single cities in the United States

(17–

19). The content of these studies focused on only AIDS, sexually transmitted diseases, and AIDS-related risk behaviors—not to mental health or health in general.

This article is based on data from the Urban Men’s Health Study, a large (N=2,881), geographically diverse (San Francisco, New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago, including areas outside gay ghettos), household-based probability sample of men who have sex with men in the United States. This article estimates the prevalence of major depression and distress in men who have sex with men and considers independent associations of depression and distress with a wide variety of health-related variables.

Discussion

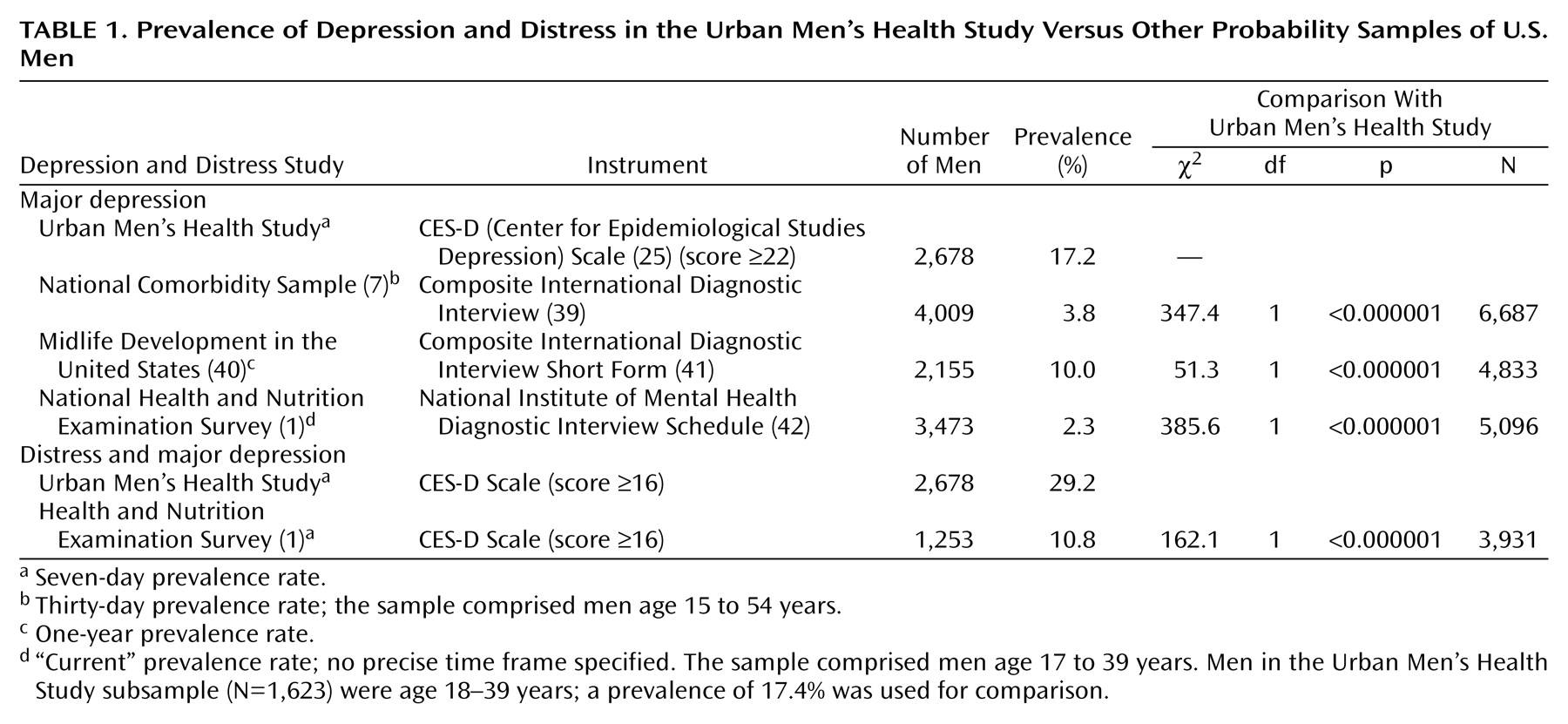

Because this data was based on a survey of men who have sex with men, there is no direct control group for the purposes of proving a difference in the rates of depression and distress between men who have sex with men and men who do not have sex with men. Nonetheless, the Urban Men’s Health Study data on men who have sex with men and the data based on other probability samples of men in general are strikingly and consistently disparate. When we compared the entire at-risk group of distressed and depressed men with the same instrument as this study, men who have sex with men are 2.7 times as likely to be in the at-risk group than a general population of men (with a probability of less than one in a million). This is consistent with an odds ratio of 2.9 for all mood disorders in men who have sex with men over other men in the Dutch NEMESIS study

(15). Different instruments and different authors define “current” as a time period of from 7 to 30 days (or decline to define it at all), further limiting the ability to make direct comparisons between studies. Even so, using each author’s definition of “current,” the “current” prevalence of depression in men who have sex with men appears to be 4.5 to 7.6 times more likely, and the differences appear significant at the level of less than one in a million. Presumably by using a scale with a short definition of “current,” such as the CES-D Scale, makes for a conservative estimate of the difference in prevalence. Even when comparing major depression in a sample that includes women (who are known to have higher rates of depression)

(1), men who have sex with men have 2.6 times higher current rates of depression than the lifetime rates in the general population (χ

2=239.2, df=1, p<0.000001, N=10,267). All these comparisons are all the more remarkable because the probability samples of the men in general included an unknown number of men who have sex with men. Although statistical proof is not possible here, the differences among these disparate studies makes it clear that further study of mental health in men should include measures of sexual orientation and behavior to more fully test these hypothetical differences.

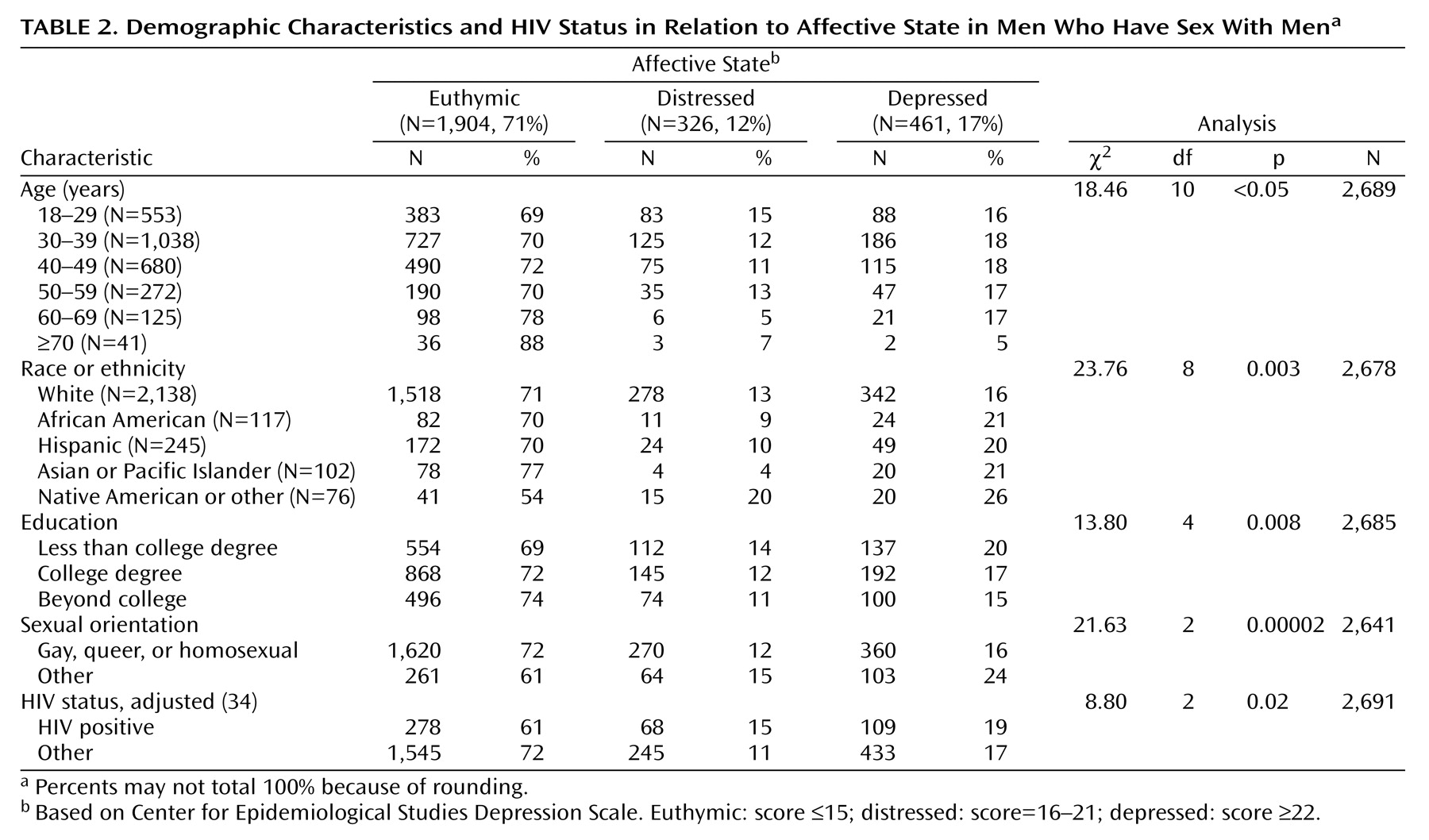

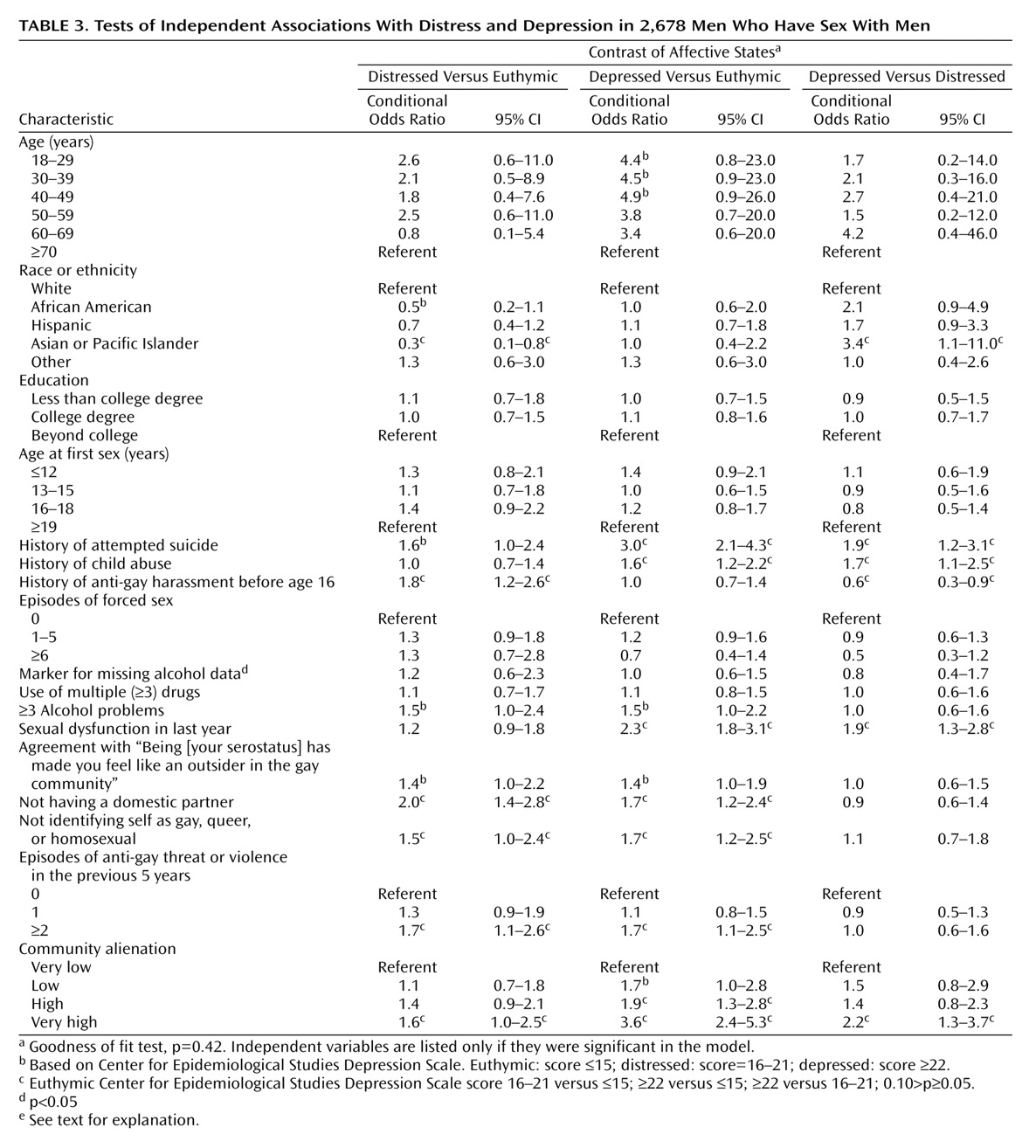

Variables associated with both distress and depression are not having a domestic partner; a recent history of anti-gay threats or violence; not identifying as gay, queer, or homosexual; and feeling highly alienated from the gay community. Not being married was associated with multiple psychiatric conditions. The other three variables may reflect homophobia—internal or external. Multivariate analysis can establish association, not causality, but these variables imply hypotheses to test causality by measuring the effectiveness of community-based interventions in improving the mental health of men who have sex with men as a group. Does the enactment of statutes legalizing marriage or domestic partnership or punishing hate crimes based on sexual orientation lead to a lower prevalence of distress and depression in men who have sex with men? Natural experiments concerning both these hypotheses are occurring as local and state governments around the United States establish these laws. Would programs developed to encourage men who have sex with men to self-identify as gay, queer, or homosexual decrease levels of depression and distress? Might programs designed to promote the notion of a community of gay men decrease levels of alienation and thereby decrease rates of distress and depression? Both of these hypotheses are testable; in some places, research infrastructure that could be used to test them is already in place in AIDS-related, community-based organizations.

Parsing distress and depression by the variables to which each is uniquely associated is more complicated. Distress, compared to euthymia, is associated with other than Asian/Pacific Islander ethnicity and a history of early anti-gay harassment. Depression, relative to euthymia, is associated with a history of suicide attempt, child abuse, sexual dysfunction, and lower levels of community alienation. Within the overall at-risk group with CES-D Scale scores of 16 or greater, depression is associated with Asian/Pacific Islander ethnicity, a history of suicide attempt, child abuse, sexual dysfunction, and very high levels of community alienation, but it is negatively associated with a history of early anti-gay harassment.

This odd configuration of associations may be due, in part, to the heterogeneity of the “distressed” category. Some unknown portion of the distressed respondents likely has mood disorders that are not severe enough to attain high CES-D Scale scores. This could account for two variables that are associated with depression when compared to distress and that tend to be significant when we compared distress and euthymia: history of suicide attempt and high levels of community alienation. Sexual dysfunction may be associated with depression severe enough to attain high CES-D Scale scores but not with less severe variants. Cultural inhibitions in Asian/Pacific Islander respondents in which depressive symptoms are minimized until they are so problematic as to be undeniable

(43,

44) could explain why, within the entire population of men who have sex with men, being of Asian/Pacific Islander extraction is protective for low-scoring mood disorders (and, hence, distress) as well as positively associated with depression in an at-risk population of men who have sex with men. The CES-D Scale may also have some cultural bias regarding U.S. Asians and Pacific Islanders. Cultural bias also may be evident in the finding that not being African American approaches significance as a predictor of distress over euthymia.

Interpretation of the pattern of associations of histories of child abuse and early anti-gay harassment is perplexing. History of child abuse is associated with depression when compared with both distress and euthymia. To the extent that child abuse is associated with dissociative defense mechanisms, men who have sex with men with this history may be less dysphoric

(45), and hence it might not correlate with higher CES-D Scale scores unless particularly toxic stressors (e.g., intrusive recollection and unsupported breach of denial) are present. History of anti-gay harassment before the age of 16 is positively associated with distress (compared with euthymia), but it is protective against depression (compared with distress). Perhaps early anti-gay harassment is more likely to produce anxiety disorders or adjustment disorders. It may also produce external objects (e.g., homophobes or gay bashers) at which anger, which otherwise might be self-directed (leading to depression), might be outwardly directed, reducing the propensity toward depression. More study is needed to better explicate the relationship of these variables to distress and depression in men who have sex with men.

The power of the overall analysis may be reduced by using three categories of CES-D Scale scores and multinomial logistic regression analysis. Therefore, several additional variables with p values between 0.05 and 0.10 should be addressed. These include age of less than 50 for depression and outsider status due to HIV status and three or more alcohol-related problems for both depression and distress. Youth is a known risk factor for depression

(7). Outsider status in HIV-negative men who have sex with men has been discussed elsewhere

(46), as has alcohol use and abuse in the Urban Men’s Health Study survey

(47).

Conspicuous by its absence is any further association between other HIV experiences and being distressed or depressed. The relationship of HIV infection and the risk for major depression has been difficult to demonstrate: finding that association required a meta-analysis of 10 studies (with a total N of 2,596), and a meta-analysis of five of those same studies (N=1,117) was unable to locate an association between depression and the presence of symptomatic HIV disease

(48), presumably the most severe type of HIV-related stressor. The advent of protease inhibitors in 1996 and the perception of HIV disorders moving from inexorably fatal to chronic may mean that its mental health impact has diminished for both HIV-infected men who have sex with men as well as their caretakers.

This study has several limitations. As noted, because it is based on a survey of men who have sex with men, there is no direct heterosexual control group. Because the Urban Men’s Health Study was not focused on depression alone and required lengthy phone interviewing, it was not possible to cover the full gamut of issues that might be related to depression in men who have sex with men, including religiosity, early severe loss, divorce, or family history of depression or suicidality. Further research could explore these issues. Threat of violence and actual violence were not distinguished in this study; while either predicted distress or depression, actual violence may be a stronger predictor of distress and depression. Up to 15% of the depressed group may be false positives and false negatives

(29,

30).

Although some of those false positives might be people with other mood disorders, such as a depressive episode of bipolar disorder or severe dysthymic disorder, their diagnosis is not of a major depressive disorder per se. Men who have sex with men who do not identify themselves as gay, queer, or homosexual may have been more likely to deny homosexual behavior and hence not to participate in the survey. Nonetheless, 16% of the men who have sex with men who were interviewed self-identified as bisexual, heterosexual, or other

(20). Given that this study was cross-sectional in nature, any imputation of causality is ill-advised; proof of causality would require a cohort study. The sample frame excluded some men who have sex with men who live in urban areas with a low proportion of men who have sex with men, as well as those residing in small cities, in suburbs, or in rural areas. As probability sampling of these areas for men who have sex with men is prohibitively expensive, network sampling

(49,

50) may be the sampling method of choice—albeit with significant limitations—to study these populations. Men who have sex with men of color are underrepresented in this study due to in-migration

(20), and men who have sex with men of color may also be less likely to disclose sexual orientation or preferentially live in areas of the cities not sampled

(32). The sample excluded a priori adolescent men who have sex with men and the 5% of the households in these cities that do not have telephones

(51,

52). Convenience samples may be the only way to reach some subgroups of the very poor, such as those who are homeless; interviewing adolescents requires complicated (and probably biasing) parental consent.

The prevalence of depression in men who have sex with men is comparable to the prevalence of HIV seropositivity in men who have sex with men

(20), and, like HIV disease, depression is chronic and enormously expensive in terms of lost wages, disability, cost of treatment, and decrease in life expectancy. In addition to treating individual men who have sex with men with depression or distress, public health efforts to prevent these conditions might also be attempted at the level of structural interventions designed to change the social environment in which men who have sex with men live. The relationships described in this article suggest that communities of men who have sex with men might experience lowered rates of distress and depression if efforts were made to encourage acknowledgment of sexual orientation or enhance community building to decrease the sense of alienation from the gay community for some men who have sex with men. Furthermore, the relationships described herein also suggest that encouragement of long-term intimate relationships between men who have sex with men (such as domestic partnership laws) and effective hate crime legislation might also reduce rates of distress and depression in men who have sex with men. There exist opportunities to measure how social policy changes might yield important health outcomes at the level of the individual. Efforts to take advantage of natural experiments that are created as changes in social policy about men who have sex with men and their central relationships may well yield important understandings in how to support health and social functioning in other marginalized populations.