Among the elderly, bipolar disorder represents 5%–19% of the mood disorder presentations to psychiatric care

(1). Studies show evidence of cognitive deterioration in the longitudinal assessment of older patients with bipolar disorder

(2) and greater cognitive impairment in older than younger patients

(3). There is growing evidence of cognitive dysfunction in euthymic mixed-age patients

(4). To date, we know of no published study of cognitive functioning in

older adults with bipolar disorder that has included only euthymic subjects. We report on the cognitive functioning of a group of patients with bipolar disorder (N=18), 60 years and older, who were euthymic at the time of testing.

Method

Eighteen patients with either bipolar disorder I or II entered into the analysis, a federally funded treatment study of bipolar disorder in the elderly. Subjects were recruited from university geropsychiatric inpatient and outpatient clinics in various illness phases (depressed, euthymic, manic, or mixed). The subjects who entered the study in a euthymic state received neuropsychological testing at study entry. The subjects who entered in a noneuthymic state received neuropsychological testing at study entry and approximately 3 months after initial testing if euthymia had been established. Twenty subjects who had neuropsychological testing when euthymic were considered for inclusion in this analysis. Two were excluded to avoid the confounding effects of preexisting dementia (N=1) and maintenance ECT (N=1). Two subjects with a remote history of alcohol abuse were included in the analysis. No subject had current active substance abuse or dependence. Twelve subjects had bipolar I disorder, and six subjects had bipolar II disorder.

A total of 45 age- and education-equated comparison subjects had undergone neuropsychological testing while participating in ongoing research projects. They had no current or lifetime history of psychiatric disorder, except for one subject who had a history of simple phobia.

We performed cognitive assessments with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE); the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale

(5), an assessment of cognitive impairment in domains of attention, initiation/perseveration, construction, conceptualization, and memory; and the Executive Interview

(6), an instrument assessing a broad array of executive cognitive functions, with higher scores indicating greater executive dyscontrol.

Written informed consent was obtained after the study had been fully explained to each of the subjects. All cognitive assessments in this study were performed on subjects determined to be euthymic at the time of testing (and clinically stable for at least the preceding 4 weeks) based on scores of 10 or less on both the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

(7) and the Young Mania Rating Scale

(8). The subjects with bipolar disorder were taking the following medications: lithium (N=7; mean level=0.66 meq/liter, SD=0.26), valproate (N=4; mean level=79.5 μg/ml, SD=15.6), olanzapine (N=1), lamotrigine (N=1), or combination therapy (N=4; lithium, olanzapine, and/or valproate). One subject with bipolar disorder was taking no mood stabilizer at the time of testing. The results of neuropsychological testing performed on these 18 bipolar subjects were compared with the results from the 45 comparison subjects.

Results

The bipolar subjects had a mean age of 68.7 years (SD=8.0, range=60–84); 72% of the participants were women, and 89% were Caucasian. They had a mean 15.1 years of education (SD=3.4), a mean Hamilton depression scale score of 5.6 (SD=2.9), and a mean Young Mania Rating Scale score of 2.6 (SD=2.6). The subjects with bipolar I or II did not differ on age, education, or scores on the Hamilton depression scale or the Young Mania Rating Scale but had statistically different mean levels on the Global Assessment Scale (GAS)

(9) (mean=68.4, SD=8.4, versus mean=79.5, SD=7.4; p<0.03, Wilcoxon’s exact test, two-sided). The comparison subjects had a mean age of 70.2 years (SD=6.8, range=57–84) and had a mean 14.0 years of education (SD=2.8). There were no significant differences between the bipolar and comparison subjects on age (t=–0.78, df=61, p=0.44) or education (t=1.16, df=61, p=0.21).

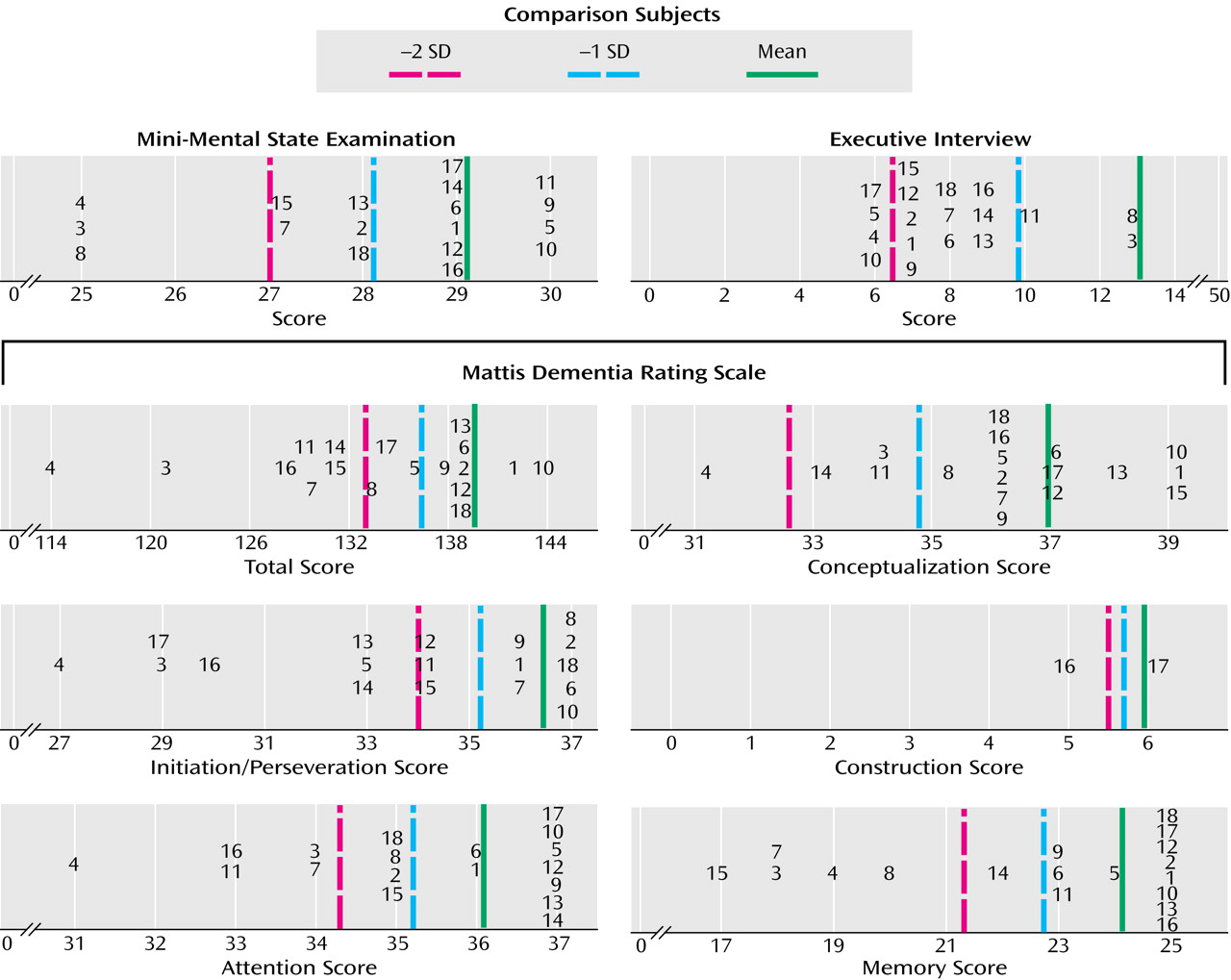

Approximately half of the bipolar subjects scored one or more standard deviations below the mean of the comparison subjects on the MMSE (N=8, 44%) and the total Mattis Dementia Rating Scale (N=10, 56%) (

Figure 1). The bipolar subjects scored one or more standard deviations below the comparison subjects on the following Mattis Dementia Rating Scale subscales: initiation/perseveration (N=10, 56%), attention (N=9, 50%), memory (N=6, 33%), conceptualization (N=4, 22%), and construction (N=1, 6%). On the Executive Interview, three subjects (17%) scored between one and two standard deviations above the comparison mean, indicating impairment. There was a significant difference between scores of the bipolar subjects and the comparison subjects on the MMSE (mean=28.2, SD=1.7, versus mean=29.1, SD=1.1; p<0.03), the total Mattis Dementia Rating Scale (mean=133.8, SD=7.5, versus mean=139.6, SD=3.4; p=0.0006), the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale initiation/perseveration subscale (mean=33.8, SD=3.2, versus mean=36.4, SD=1.2; p=0.00004), and the Executive Interview (mean=8.1, SD=2.1, versus mean=6.5, SD=3.3; p<0.02). (All statistics are Wilcoxon’s exact tests, two-sided.)

We examined correlations between demographic and clinical variables on cognitive functioning (Spearman’s correlations). Age was inversely correlated with scores on the MMSE (r=–0.63, df=16, p<0.006) and memory subscale (r=–0.50, df=16, p<0.04). Education was positively correlated with scores on the MMSE (r=0.53, df=16, p<0.03), the total Mattis Dementia Rating Scale (r=0.55, df=16, p<0.02), attention (r=0.84, df=16, p<0.0001), and memory (r=0.57, df=16, p<0.02). Scores on the GAS, the Hamilton depression rating scale, and the Young Mania Rating Scale were not associated with any cognitive variables. Neither age of first episode nor duration of illness was associated with any of the cognitive variables. We observed no association between the mood stabilizers employed and the cognitive variables.

Conclusions

More than half of the elderly euthymic bipolar subjects exhibited significant deficits on neuropsychological tests compared with age- and education-equated comparison subjects. Our findings are consistent with and extend those from studies of younger euthymic bipolar subjects that have shown deficits in sustaining attention and executive control of working memory

(10,

11).

Although our findings are compelling, our study has several limitations. The group size was small, with “young-old” subjects who are more highly educated than the general population. The MMSE and Executive Interview are “bedside” instruments that provide only an overall assessment of cognitive functioning. The Mattis Dementia Rating Scale, while more comprehensive, does not provide fine-grained characterization of cognitive functioning: it only captures moderate to severe impairment. Last, we were unable to examine the effect of a number of acute relapses on cognitive functioning because data on the number of relapses were not available.

Notwithstanding these limitations, our findings point to further work being necessary to understand how bipolar disorder affects cognitive function in older adults and whether bipolar disorder is a risk factor for subsequent dementia. Given that elderly patients with bipolar disorder represent a heterogeneous group (with different ages of illness onset, numbers of acute relapses, and medical comorbidities), the causes of cognitive impairment in this population are likely heterogeneous. Neurodevelopmental anomalies, the “toxicity” of mood episodes, vascular disease, comorbid history of substance use, and medication side effects are all potential contributors to cognitive dysfunction (4), as well as potential targets for intervention to alleviate an important component of disability among older adults with bipolar disorder.