The diagnosis of borderline personality disorder, even when the self-injury criterion is excluded, has been associated with suicidal behaviors

(1,

2). Furthermore, borderline personality disorder has been demonstrated to have higher associations with suicidal behaviors than major depressive disorder, another disorder with a suicide-related criterion

(2,

3). Given the heterogeneity of borderline personality disorder, identification of borderline personality disorder features associated with suicidal behaviors could lead to better prediction and more specific interventions.

Brodsky et al.

(1) examined the relationship between characteristics of borderline personality disorder and suicidal behaviors and found that after lifetime diagnoses of depression and substance abuse were controlled, impulsivity was the only criterion of borderline personality disorder (excluding self-injury) associated with a higher number of previous suicide attempts. History of childhood abuse was also significantly correlated with number of lifetime suicide attempts

(1). The present study

prospectively examines the association of borderline personality disorder criteria, major depressive disorder, substance use disorders, and childhood sexual abuse over a 2-year period. This is the second report on predictors of suicidal behaviors from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study. The first examined diagnostic predictors and found that borderline personality disorder, drug use disorder, and course of major depressive disorder and substance use disorders prospectively predicted suicide attempts

(2). Here, we hypothesized that impulsivity would be the borderline personality disorder criterion having the strongest association with prospective suicidal behaviors (defined as any suicide-related act regardless of intent to die) and suicide attempts (defined as any suicide-related act with at least some intent to die that, at minimum, resulted in mild medical threat).

Method

The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study is a multisite, naturalistic, prospective study of four personality disorder groups (schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive) and a comparison group of major depressive disorder subjects without personality disorder. Each participant provided written informed consent after procedures had been fully explained. Following is an overview of the study participants and assessment procedures relevant to the present investigation; more detail is available elsewhere

(4).

Participants between the ages of 18 and 45 with a history of current or past psychiatric treatment were recruited at each of the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study sites. Individuals were eligible to participate if they met diagnostic criteria as assessed by the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders

(5) for at least one of the four personality disorders targeted in the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study or if they met criteria for the comparison group, subjects with major depressive disorder (without personality disorder), as determined with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, patient version

(6). Each of the nine DSM-IV criteria for borderline personality disorder was assessed with the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders. Interrater and test-retest reliability for borderline personality disorder diagnoses were 0.68 and 0.69, respectively. The Revised Childhood Experiences Questionnaire

(7) and the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation

(8) were used to assess history of childhood sexual abuse and suicidal behaviors, respectively. Detailed ratings of intent (obviously no intent, only minimal, definite but very ambivalent, serious, very serious, and extreme intent) and medical threat (no threat, minimal, mild, moderate, severe, and extreme danger) were made.

Participants who reported any suicidal behaviors, regardless of intent or severity, were included in the suicidal behaviors group. Participants with at least “definite, but ambivalent” intent and with attempts rated at least as being of mild medical threat were included in the suicide attempt group. Specific group comparisons of interest to the current report include 1) suicidal behaviors versus no suicidal behaviors and 2) suicide attempts versus no suicide attempts during 2 years of follow-up. Follow-up assessments were made at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years postbaseline. The present examination focuses on 621 of the 668 Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study participants (93% of sample) with at least 12 months of follow-up data. The majority of the sample (86.5%, N=578) had 2 years of follow-up data at the time of analyses.

To examine prospectively associations with suicidal behaviors and suicide attempts, each criterion of borderline personality disorder (excluding self-injury) was entered as an independent variable in two separate logistic regression analyses. These analyses were also conducted after covarying for the self-injury criterion to determine if other borderline personality disorder criteria remained significant. Covariates, selected a priori, were major depressive disorder, substance use disorders, and childhood sexual abuse.

Results

Of the 621 subjects, 95 (15.3%) reported suicidal behaviors during the 2 years of follow-up, and a subgroup of 58 (9.3%) reported a suicide attempt. Borderline personality disorder was prevalent in both groups (79% and 78%, respectively).

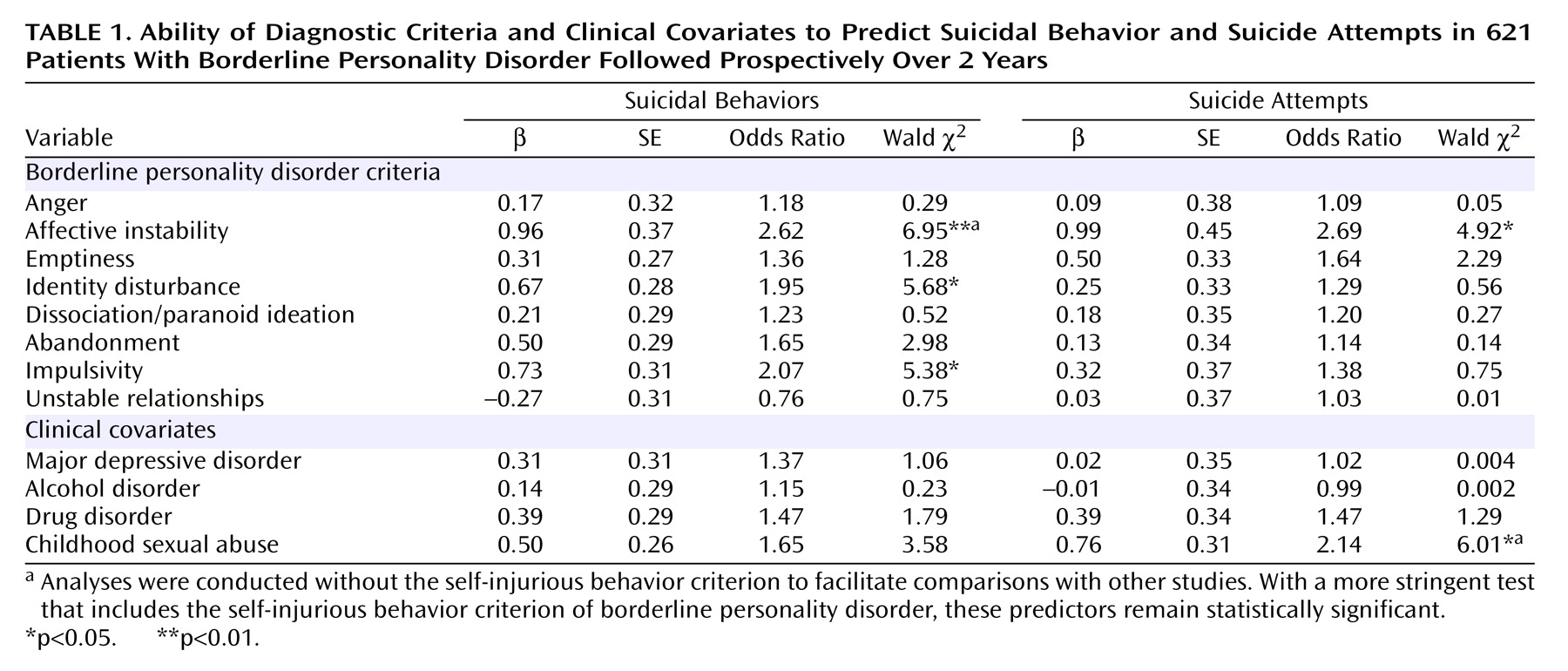

Table 1 shows three borderline personality disorder criteria predicted suicidal behaviors: affective instability, identity disturbance, and impulsivity (in order of significance). None of the covariates (major depressive disorder, substance use disorder, or childhood sexual abuse) were significant. When predicting suicide attempts, only the borderline personality disorder criterion of affective instability was significant. However, unlike the analyses predicting suicidal behaviors, childhood sexual abuse was a significant covariate in the regression analysis predicting suicide attempts. Both affective instability (for suicidal behaviors) and childhood sexual abuse (for suicide attempts) remained significant even after covarying for history of self-injury.

Discussion

Affective instability was the borderline personality disorder criterion most strongly related to both suicidal behaviors and suicide attempts. This is noteworthy in light of the finding that baseline major depressive disorder was not significantly associated with either. Furthermore, the finding for suicidal behaviors remained even after covarying for the borderline personality disorder self-injury criterion. This suggests that reactive mood shifts associated with this criterion may account for suicidal behaviors more so than negative mood per se.

Some criteria (identity disturbance, impulsivity) were significant predictors of suicidal behaviors but were not significant in the context of more serious suicide attempts. Conversely, childhood sexual abuse, not a significant predictor of suicidal behaviors, significantly predicted suicide attempts. This suggests that there may be specific risk factors associated with suicide attempts aside from those related to other suicidal behaviors (which include gestures). This highlights the importance of developing a standard nomenclature or classification system for suicide-related behaviors

(9). Specifically, identity disturbance and impulsivity may be more salient factors in suicidal behaviors (particularly gestures), whereas childhood sexual abuse appears to be associated with more serious suicidal behaviors, such as attempts.

Consistent with Brodsky et al.’s findings, impulsivity significantly predicted suicidal behaviors, although in the present study it was not the strongest predictor. Our study group was broadly selected from different levels of care to be fully representative of the spectrum of personality disorder pathology. Brodsky et al.’s homogenous study group of borderline personality disorder inpatients may have reduced the variance in their associated variables. Although we decided not to restrict analyses to borderline personality disorder subjects for generalizability purposes, the majority of participants who reported suicidal behaviors met diagnostic criteria for borderline personality disorder. The results from the present report suggest the importance of identifying affect instability as a risk for subsequent suicidal behaviors and to target it in treatment.