Design

All subjects were recruited through advertisements requesting participants for a study about trauma and addiction. Eligible patients were randomly assigned to one of two active treatment conditions: seeking safety or relapse prevention. Treatments were conducted in twice-weekly 1-hour individual sessions for 12 consecutive weeks. A nonrandomized community care comparison group served as a nonspecific comparison condition. This design follows the criteria of stage IB behavioral therapies research

(17), which allows for a preliminary stage efficacy trial with a nonrandomized, quasi-experimental comparison group. The community care comparison condition strengthened our design by allowing us to examine whether seeking safety and relapse prevention were more effective than other routinely sought out substance abuse treatments.

The 32 women in the community care group met the same diagnostic criteria and were recruited in the same manner as those in the two cognitive therapy groups but were not offered either of the two manualized therapies. If interested, they were given the same list of treatment referrals as those in the manualized therapy groups. They were followed longitudinally for the same pretest-posttest assessment periods. Over the 3-month active treatment phase, seven (22%) of the subjects in the community care group received outpatient psychological treatment, seven were prescribed psychiatric medication, and two (6%) were hospitalized for psychiatric reasons. Nine (28%) reported receiving any drug or alcohol treatment, and five (16%) reported attending self-help meetings.

The patients in the two manualized study treatments (seeking safety and relapse prevention) received standard care in the community similar to the care received by the community care group. Over the 3-month study period, 22 (29%) received outpatient psychological treatment, 14 (19%) received prescription medications, four (5%) were hospitalized for psychiatric reasons, 15 (20%) received any drug or alcohol treatment, and 18 (24%) reported attending self-help meetings. Neither active treatment group statistically differed from the community care group in this comparison.

Participants

Participants were treatment-seeking women who responded to an advertisement or were referred from substance use treatment programs in a major metropolitan area. Women met screening criteria for the presence of a lifetime traumatic event (defined as positive response to items from the Lifetime Trauma Events Scale adapted from Fullilove et al.

[5]).

Screening inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) age 18 through 55 years, 2) female, 3) diagnosis of substance use disorder, 4) a history of at least one DSM-IV-defined trauma event, and 5) English-speaking. Patients who met these initial eligibility criteria received further diagnostic screening.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) advanced-stage medical disease (e.g., AIDS, tuberculosis) as indicated by global physical deterioration and incapacitation, 2) organic mental syndrome (associated with chronic drug abuse), and 3) psychiatric exclusions, defined below.

All women who met screening eligibility criteria (N=207) were asked to participate in a diagnostic interview. Interviewers obtained written informed consent before the interview. Each participant received $10.

Patients met criteria for final eligibility (and received an additional $20 voucher for their additional interview time) if they were diagnosed with current or subthreshold PTSD (defined as DSM-IV criteria A, B, and E and the presence of either C or D) and current DSM-IV substance dependence; if they reported using substances at least three times a week on the Substance Use Inventory

(18); and if their Mini-Mental State Examination score was greater than 21. Psychiatric exclusion criteria included 1) current active suicidality, 2) current axis I diagnoses other than atypical bipolar, depressive, or anxiety disorders, and 3) history of psychosis.

Of the 128 women who met full study eligibility criteria, 115 (90%) agreed to participate, and 96 of these women were randomly assigned to active treatment. Thirty-two of the 128 women became the community care comparison group. Baseline data were available for 115 of the women entered into the study. Of the 96 women randomly assigned to active treatments, 75 (78%) attended at least one psychotherapy session and were included in the intent-to-treat group. Thus, the total number of subjects was 107 (75 in active treatment and 32 in community care). There were no significant differences in demographics, treatment history, or baseline symptom severity between those who entered treatment and those who did not, suggesting that dropouts were random rather than attributable to any systematic bias.

Ninety-four (88%) of the 107 subjects met full criteria for current PTSD; 13 (12%) met “subthreshold” criteria. Comparative analyses of those with full and subthreshold PTSD yielded no differences in substance use, PTSD, and psychiatric symptom severity. There were no differences in distribution of subthreshold PTSD across the three study groups.

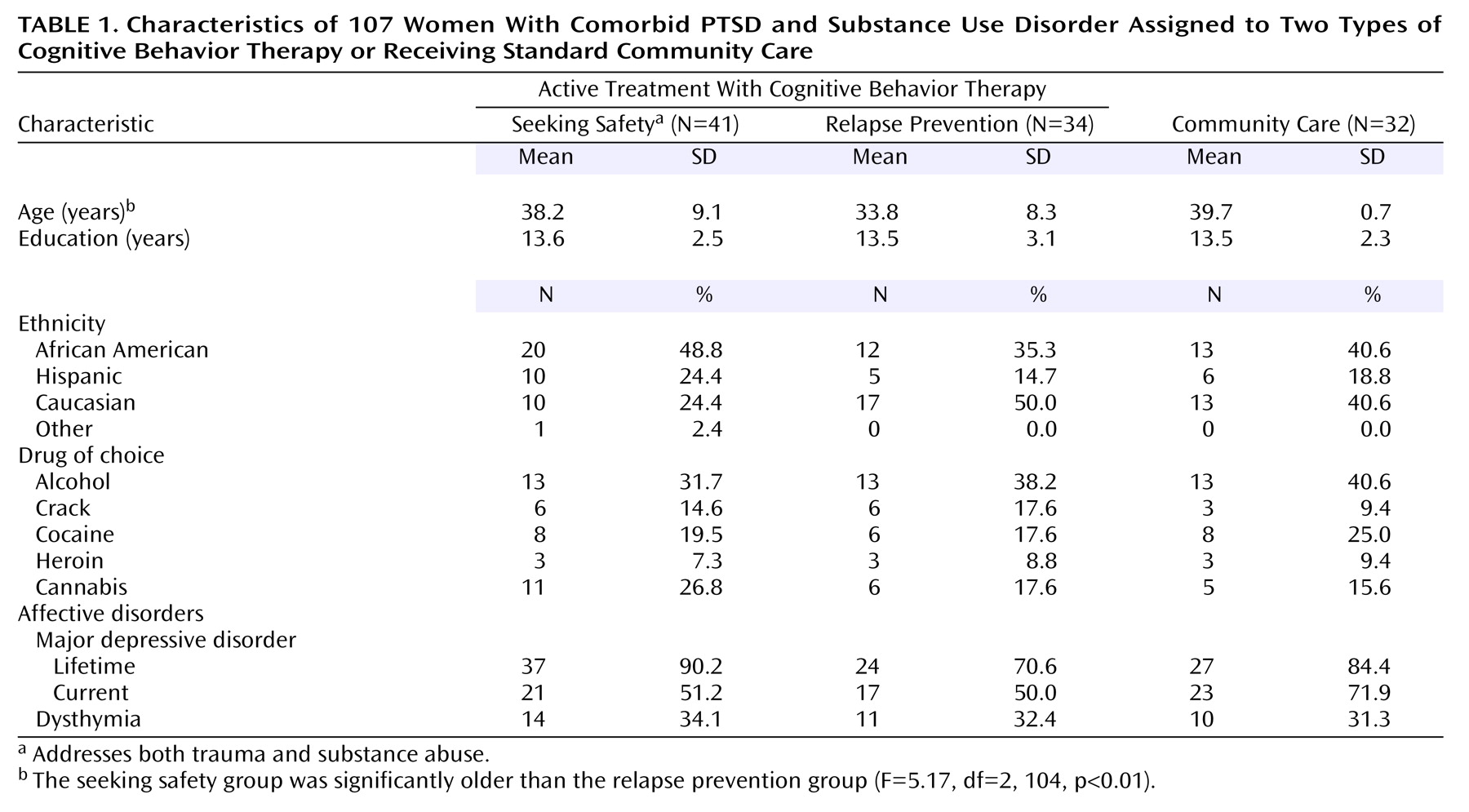

Table 1 presents the subjects’ demographic characteristics. The groups differed significantly only in age: the seeking safety group was significantly older than the relapse prevention group (

Table 1). Therefore, age was entered as a covariate in all analyses.

Study participants in all three conditions received repeated-measures assessments at baseline, end of treatment (3 months after baseline), 6 months after baseline, and 9 months after baseline. The primary outcomes assessed were substance use and PTSD symptoms. The secondary outcomes were global psychiatric symptoms. Additionally, for patients in the two active treatment groups, feasibility and acceptability were examined through adherence and dropout rates.

Measures

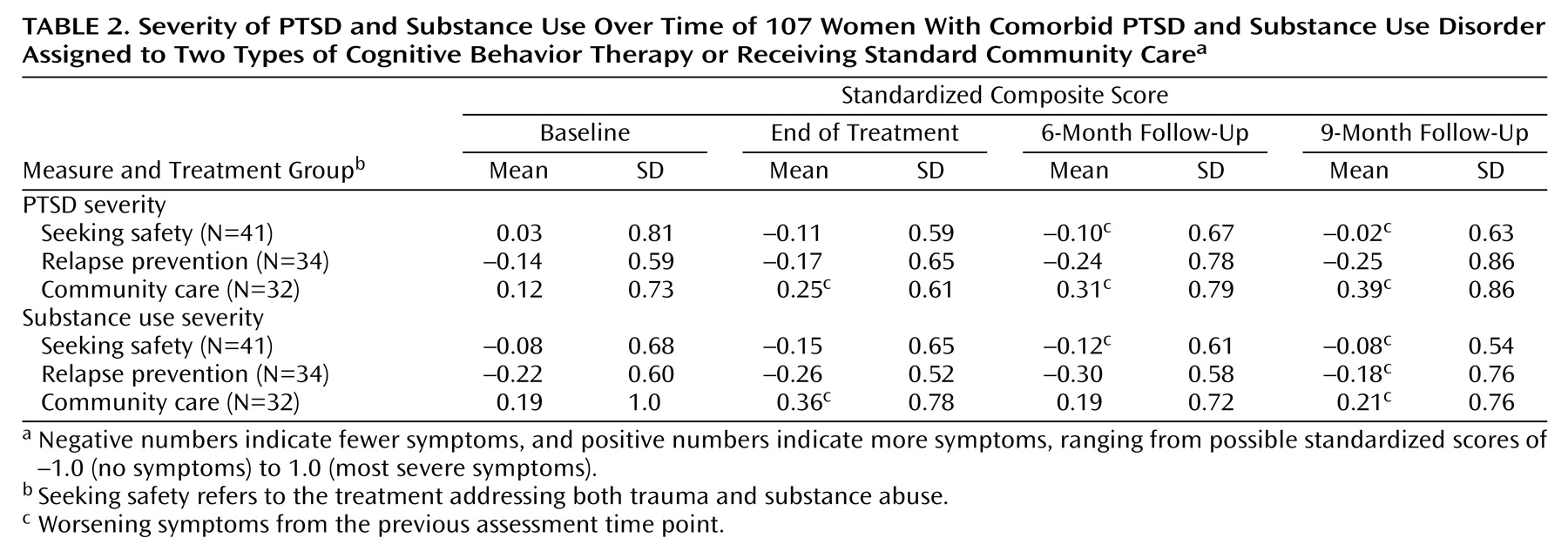

To reduce the possibility of Type I error, standardized composite scores were created for the two primary outcome domains of substance use and PTSD severity, as well as for the secondary outcome domain of global psychiatric symptoms. Intercorrelation matrices of all standardized measure total scores relevant to a specific outcome were created to determine which had reliability coefficients (alpha) of at least 0.85. Composite scores for each construct (substance use, PTSD, and global psychiatric symptoms) were then created by using a mean of all standardized scores meeting reliability criteria. Standardized scores range from –1 to 1. A score approaching –1 can be interpreted as low severity relative to a score approaching 1, whereas a score close to 0 falls at the midpoint. Individual measures that were used to create the respective outcome composites are described below.

Substance use severity composite individual measures

The Substance Use Inventory

(18), which consists of self-report questions, was used to determine quantity (i.e., dollars spent per day) and frequency (i.e., days) of substance use over the past week. Substances included opiates, cocaine, alcohol, marijuana, amphetamines, sedatives, phencyclidine, and prescription medications. Outcomes were based on the mean rating of use over the previous 4 weeks.

The Clinical Global Impression (CGI)

(19), a series of 7-point, interviewer-rated scales, was used to measure substance abuse. The CGI uses interview and clinical data to characterize abuse severity and improvement for cocaine, opiates, other drugs, and alcohol. Outcomes were the mean rating for use of each substance over the previous 4 weeks.

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID)—SAC Version

(20,

21), a modified version of the SCID, was used to detect the presence of primary, persistent, and drug-use-independent psychiatric disorders in drug abusers. The present study evaluated mood, anxiety, psychotic, alcohol, and psychoactive substance use disorders.

PTSD severity composite individual measures

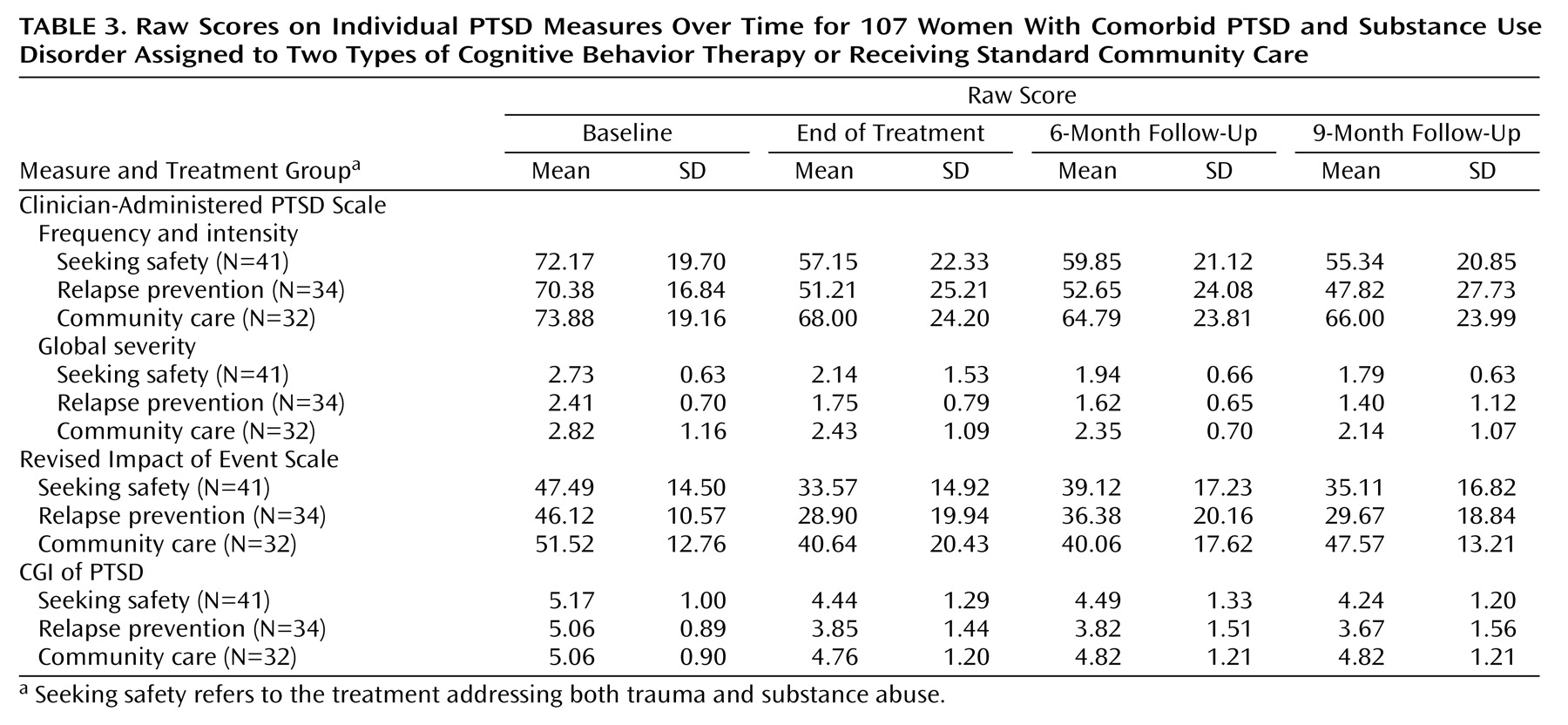

The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale

(22), a structured clinical interview, was used to assess the frequency, intensity, and global severity of DSM-IV PTSD symptoms. It also measured the impact of symptoms on social and occupational functioning, the degree of improvement since an earlier rating, and the validity of responses.

The revised Impact of Event Scale

(23), a 15-item self-report questionnaire, was used to assess symptoms of intrusion and avoidance on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 5 (often). The scale evaluated the most stressful life event(s) the participant had experienced and the frequency of statements that pertain to those events.

The CGI of PTSD

(19), a series of 7-point, interviewer-rated scales, used interview and clinical data to characterize global PTSD severity and improvement over the previous 4 weeks.

Global psychiatric severity composite individual measures

The CGI

(19) was used to determine global severity of psychiatric symptoms. Depression symptom rating scales were also used. The Global Assessment Scale

(24) evaluated average overall psychiatric functioning and impairment over the past 4 weeks; scores range from 1 (lowest) to 100 (highest). The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

(25), a widely used 15-item Likert-type rating scale, was used to assess degree and range of depressive symptoms.

Treatment services

The Treatment Services Review

(26), a brief interview, elicited the variety and frequency of services received during the past week. The Demographic and Treatment History Form (D. Hien and S. Zimberg 1991, unpublished), a structured 62-item social and treatment history interview, provided basic demographic and life history information.

Quality assurance

Urine screens were taken to confirm self-reported abstinence and were used only to ensure validity of self-report. We planned to assign a positive finding for substance use if discrepancies were observed between self-report and urine data, but such discrepancies did not occur in this group of subjects.

To test for diagnostic reliability, a random sample of 25% of all diagnostic interviews was audiotaped and a Ph.D.-level assessment supervisor reviewed diagnoses. Therapists were trained and certified by expert trainers in both seeking safety and relapse prevention therapies; therapists were required to meet adherence and competence standards set forth by each respective treatment manual guidelines before initiation of the study. Quality assurance for treatment fidelity was conducted by having 25% of the treatment sessions randomly rated for adherence and competence by expert consultants. Experts’ ratings revealed high levels of competence for all participating therapists. Therapists were experienced predoctoral and master’s-level clinicians.

General Data Analytic Strategies

To check on the study design’s internal validity, baseline data were analyzed for differences among the seeking safety, relapse prevention, and community care conditions. No statistically significant differences were found in baseline symptom severity, indicating that the quasi-experimental design maintained equivalence of groups before intervention. (

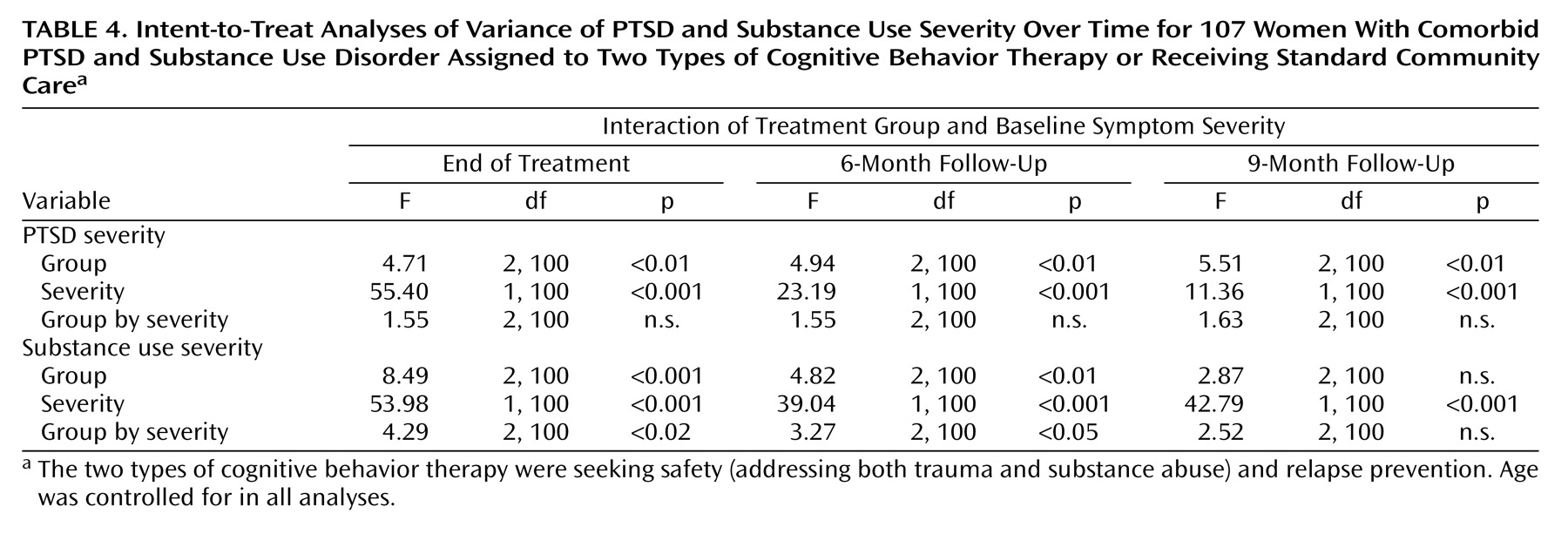

Table 2 provides baseline means and standard deviations.) Because baseline symptom severity was consistently correlated with severity at follow-up, all analyses included the baseline symptom level corresponding to each outcome domain as one of the factors in the analysis of variance (ANOVA). Six two-by-three (baseline symptom severity corresponding to outcome domain by treatment group) ANOVA analyses examined the two primary outcomes at the end of treatment and at 6-month and 9-month follow-ups. Bivariate analyses were conducted to determine potential covariates for multivariate analyses.

Data reduction strategies and multivariate testing were used to minimize the number of statistical tests. Post hoc tests were conducted to examine predicted differences between seeking safety and relapse prevention and between relapse prevention and community care only when main effects were found to be significant at p<0.05. Since we were particularly interested in differences between seeking safety and community care, a priori post hoc tests compared differences between these groups regardless of whether the omnibus tests were significant.

Intent-to-Treat Sample

Application of the criterion that participants had to attend at least one session to be considered part of the intent-to-treat group yielded data on treatment efficacy at end of treatment for 41 seeking safety, 34 relapse prevention, and 32 community care subjects (total N=107). All analyses were conducted with the intent-to-treat group as well as a “completer” group (N=81: 25 seeking safety, 24 relapse prevention, and 32 community care). A sample size of 25–30 per group has been identified as sufficient to detect clinically significant differences between two active treatments

(27). The completer group consisted of all community care participants and those in the two active treatment groups who had attended at least 25% of all therapy sessions. This definition is standard in psychotherapy research, particularly with difficult-to-treat populations

(14). Given that all findings from the intent-to-treat and the completer groups were consistent, we present only the more conservative intent-to-treat findings. The last-observation-carried-forward strategy, whereby the missing time point was replaced with the last recorded assessment point, was used for patients who could not be located for follow-up assessment. Other missing data procedures (i.e., mean replacement) were also tested, yielding no differences with the last observation carried forward procedure.

Sixty (80%) of the patients randomly assigned to active treatment received at least one session. Our retention rates were generally high: 75% (N=67) at completion of treatment and 80% (N=65) at 6-month and 9-month follow-ups. There was no differential attrition across the two treatment groups.